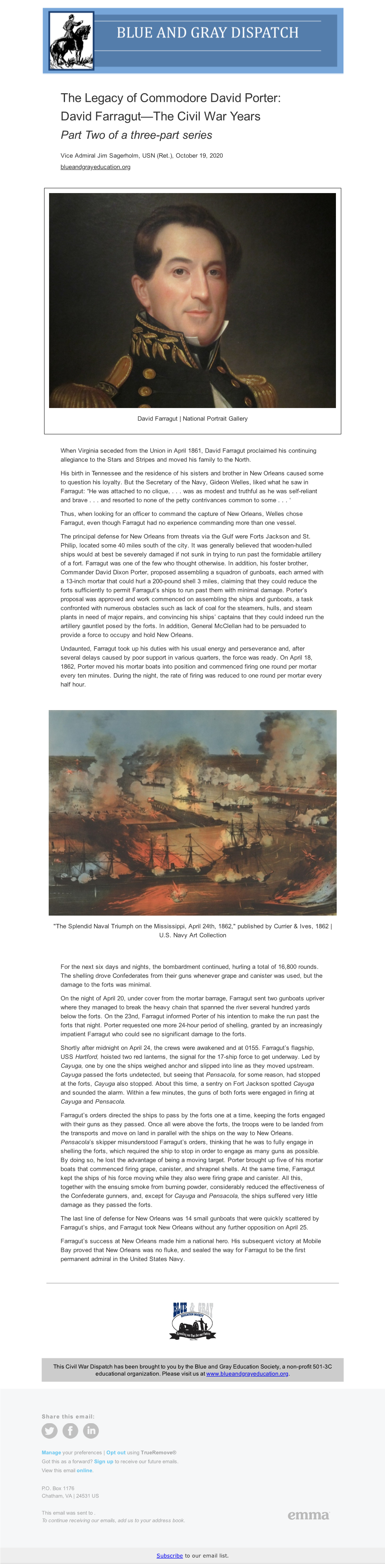

The Legacy of Commodore David Porter: David Farragut—The Civil War Years Part Two of a Three-Part Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GUSTAVUS V . FOX and the CIVIL WAR by DUANE VANDENBUSCHE 1959 MASTER of ARTS

GUSTAVUS v_. FOX AND THE CIVIL WAR By DUANE VANDENBUSCHE j ~achelor of Science Northern Michigan College Marquette, Michigan 1959 Submitted to the faculty of the Graduate School of .the Oklahoma State Univ~rsity in partial fulfillment of the requirements - for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS - Aug),Ul t, 1~~0 STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY JAN 3 1961 GUSTAVUS V. FOX AND THE CIVIL WAR Thesis Approved: _, ii 458198 PREFACE This study concentrates on the .activities of Gustavus V. Fox, Union Assistant Secretary of the Navy during the Civil War. The. investi- gation considers the role that Fox played in shaping the plans and pol- icies of the Union Navy during that conflict. The obvious fact emerges that_Fox wa; the official of foremost i~po-rt~nce in the Navy Department 'in planning all the major naval opel:'ations undertaken.by that branch of the service d~ring the Civil War. For aid on _this paper I gratefully acknowledge the following: Mr. Alton Juhlin, · Head of the Special Services Department of the University Library, for able help in acquiring needed materials for my study; Dr. Theodore L. Agnew, _wh<J critically read an·d willing assisted ·at all times; . Dr. Norbert R. Mahnken, who brought clarity and style to my subject; Dr. Homer· L. Knight, Head of the Department of History, who generously ad- vhed me in my work and encouraged ·this research effort; and Dr. John J. Beer, who taught me that there i~ more to writing than·putting woras on paper. Finally, I deeply appreciate the assistance of Dr. -

Admiral David G. Farragut

May 11, 2017 The Civil War: April 12, 1861 - May 9, 1865 Bruce W. Tucker portrays “Admiral David G. Farragut, USN” Join us at 7:15 PM on the USS LEHIGH/USS Monitor Naval Living History group Thursday, May 11th, and Corresponding Secretary of the Navy Marine Living at Camden County History Association. College in the Connector Building, Room 101. This month’s topic is Bruce W. Notes from the President... Tucker portrays “Admiral With May upon us, the weather warms and we travel David G. Farragut, USN” around; be sure to pick up our updated flyers to distribute David Farragut began his and spread the Old Baldy message. Take advantage of life as a sailor early; he activities happening near and far. Share reports of your commanded a prize ship captured in the War of 1812 when adventures or an interesting article you read with the mem- he was just twelve years old. bership by submitting an item to Don Wiles. Thank you to those who have sent in material for the newsletter. He was born July 5, 1801, and was commissioned Mid- Last month Herb Kaufman entertained us with stories shipman in the US Navy December 17, 1810, at age 9. By of interesting people and events during the War. Check the time of the Civil War, Farragut had proven his ability out Kathy Clark’s write up on the presentation for more repeatedly. Despite the fact that he was born and raised in details. This month Bruce Tucker will portray Admiral the South, Farragut chose to side with the Union. -

Civil War Generals Buried in Spring Grove Cemetery by James Barnett

Spring Grove Cemetery, once characterized as blending "the elegance of a park with the pensive beauty of a burial-place," is the final resting- place of forty Cincinnatians who were generals during the Civil War. Forty For the Union: Civil War Generals Buried in Spring Grove Cemetery by James Barnett f the forty Civil War generals who are buried in Spring Grove Cemetery, twenty-three had advanced from no military experience whatsoever to attain the highest rank in the Union Army. This remarkable feat underscores the nature of the Northern army that suppressed the rebellion of the Confed- erate states during the years 1861 to 1865. Initially, it was a force of "inspired volunteers" rather than a standing army in the European tradition. Only seven of these forty leaders were graduates of West Point: Jacob Ammen, Joshua H. Bates, Sidney Burbank, Kenner Garrard, Joseph Hooker, Alexander McCook, and Godfrey Weitzel. Four of these seven —Burbank, Garrard, Mc- Cook, and Weitzel —were in the regular army at the outbreak of the war; the other three volunteered when the war started. Only four of the forty generals had ever been in combat before: William H. Lytle, August Moor, and Joseph Hooker served in the Mexican War, and William H. Baldwin fought under Giuseppe Garibaldi in the Italian civil war. This lack of professional soldiers did not come about by chance. When the Constitutional Convention met in Philadelphia in 1787, its delegates, who possessed a vast knowledge of European history, were determined not to create a legal basis for a standing army. The founding fathers believed that the stand- ing armies belonging to royalty were responsible for the endless bloody wars that plagued Europe. -

Turning Point: 1863

THE INQUIRY CIVIL WAR CURRICULUM BY THE AMERICAN BATTLEFIELD TRUST GOAL 5 | LESSON PLAN | MIDDLE SCHOOL Turning Point: 1863 Grades: Middle School Approximate Length of Time: 3 hours (Time includes writing the final essay.) Goal: Students will be able to argue how certain events in 1863 changed the trajectory of the war. Objectives: 1. Students will be able to complete a graphic organizer, finding key information within primary and secondary sources. 2. Students will be able to address a question about a historic event, providing evidence to support their answer from primary and secondary sources. Common Core: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.1 Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources. CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.2 Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary of the source distinct from prior knowledge or opinions. CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.4 Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including vocabulary specific to domains related to history/social studies. CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.7 Integrate visual information (e.g., in charts, graphs, photographs, videos, or maps) with other information in print and digital texts. CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.WHST.6-8.1 Write arguments focused on discipline-specific content. CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.WHST.6-8.7 Conduct short research projects to answer a question (including a self-generated The Inquiry Civil War Curriculum | Middle School Battlefields.org The Inquiry Civil War Curriculum, Goal 5 Turning Point: 1863 question), drawing on several sources and generating additional related, focused questions that allow for multiple avenues of exploration. -

Chapter 11: the Civil War, 1861-1865

The Civil War 1861–1865 Why It Matters The Civil War was a milestone in American history. The four-year-long struggle determined the nation’s future. With the North’s victory, slavery was abolished. During the war, the Northern economy grew stronger, while the Southern economy stagnated. Military innovations, including the expanded use of railroads and the telegraph, coupled with a general conscription, made the Civil War the first “modern” war. The Impact Today The outcome of this bloody war permanently changed the nation. • The Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery. • The power of the federal government was strengthened. The American Vision Video The Chapter 11 video, “Lincoln and the Civil War,” describes the hardships and struggles that Abraham Lincoln experienced as he led the nation in this time of crisis. 1862 • Confederate loss at Battle of Antietam 1861 halts Lee’s first invasion of the North • Fort Sumter fired upon 1863 • First Battle of Bull Run • Lincoln presents Emancipation Proclamation 1859 • Battle of Gettysburg • John Brown leads raid on federal ▲ arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia Lincoln ▲ 1861–1865 ▲ ▲ 1859 1861 1863 ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ 1861 1862 1863 • Russian serfs • Source of the Nile River • French troops 1859 emancipated by confirmed by John Hanning occupy Mexico • Work on the Suez Czar Alexander II Speke and James A. Grant City Canal begins in Egypt 348 Charge by Don Troiani, 1990, depicts the advance of the Eighth Pennsylvania Cavalry during the Battle of Chancellorsville. 1865 • Lee surrenders to Grant at Appomattox Courthouse • Abraham Lincoln assassinated by John Wilkes Booth 1864 • Fall of Atlanta HISTORY • Sherman marches ▲ A. -

The Americans

INTERACT WITH HISTORY The year is 1861. Seven Southern states have seceded from the Union over the issues of slavery and states rights. They have formed their own government, called the Confederacy, and raised an army. In March, the Confederate army attacks and seizes Fort Sumter, a Union stronghold in South Carolina. President Lincoln responds by issuing a call for volun- teers to serve in the Union army. Can the use of force preserve a nation? Examine the Issues • Can diplomacy prevent a war between the states? • What makes a civil war different from a foreign war? • How might a civil war affect society and the U.S. economy? RESEARCH LINKS CLASSZONE.COM Visit the Chapter 11 links for more information about The Civil War. 1864 The 1865 Lee surrenders to Grant Confederate vessel 1864 at Appomattox. Hunley makes Abraham the first successful Lincoln is 1865 Andrew Johnson becomes submarine attack in history. reelected. president after Lincoln’s assassination. 1863 1864 1865 1864 Leo Tolstoy 1865 Joseph Lister writes War and pioneers antiseptic Peace. surgery. The Civil War 337 The Civil War Begins MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW Terms & Names The secession of Southern The nation’s identity was •Fort Sumter •Shiloh states caused the North and forged in part by the Civil War. •Anaconda plan •David G. Farragut the South to take up arms. •Bull Run •Monitor •Stonewall •Merrimack Jackson •Robert E. Lee •George McClellan •Antietam •Ulysses S. Grant One American's Story On April 18, 1861, the federal supply ship Baltic dropped anchor off the coast of New Jersey. -

The Civil War Background Chapter 16 from 7Th Grade Textbook

The Civil War Background Chapter 16 From 7th Grade Textbook The Debate over Slavery Seeds of War - In 1850, different Senators made proposals to maintain peace - As a result of winning the Mexican-American War in 1848, US has - After debate, it was decided that added over 500,000 sq. miles of land - California would enter the Union as a Free State - With all the new territory, people were spreading out further and along - Territory from the Mexican Cession was divided into Utah and New with that, came the issue of taking with them their Slaves Mexico and citizens there would decide whether they would allow - Northerners formed a Free-Soil Party to support the Wilmot Proviso slavery or not which stated that “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude shall ever - Texas gave up slavery in exchange for $$ from federal gov’t exist in any part of [the] territory.” - Outlawed slavery in Washington DC - Those living in the South wanted to maintain Slavery - Established a new Fugitive Slave Law - New States of Missouri & California want to be admitted to US but - Southerners were upset that California was a Free State there is a debate about allowing it in as a Free or Slave owning state - Northerners were opposed to Fugitive Slave Act and protested, many peacefully, but violence did erupt Antislavery Literature - The most important piece of literature of this era was Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe published in 1852 - Stowe based novel on interviews with “fugitive” slaves’ accounts of their lives in captivity-- she was 21 and living in Ohio - Summary: “A kindly enslaved African American named Tom is taken Election of 1856 from his wife and sold ‘down the river’ in Louisiana. -

VMI Men Who Wore Yankee Blue, 1861-1865 by Edward A

VMI Men Who Wore Yankee Blue, 1861-1865 by Edward A. Miller, ]r. '50A The contributions of Virginia Military Institute alumni in Confed dent. His class standing after a year-and-a-half at the Institute was erate service during the Civil War are well known. Over 92 percent a respectable eighteenth of twenty-five. Sharp, however, resigned of the almost two thousand who wore the cadet uniform also wore from the corps in June 1841, but the Institute's records do not Confederate gray. What is not commonly remembered is that show the reason. He married in early November 1842, and he and thirteen alumni served in the Union army and navy-and two his wife, Sarah Elizabeth (Rebeck), left Jonesville for Missouri in others, loyal to the Union, died in Confederate hands. Why these the following year. They settled at Danville, Montgomery County, men did not follow the overwhelming majority of their cadet where Sharp read for the law and set up his practice. He was comrades and classmates who chose to support the Common possibly postmaster in Danville, where he was considered an wealth and the South is not difficult to explain. Several of them important citizen. An active mason, he was the Danville delegate lived in the remote counties west of the Alleghenies where to the grand lodge in St. Louis. In 1859-1860 he represented his citizens had long felt estranged from the rest of the state. Citizens area of the state in the Missouri Senate. Sharp's political, frater of the west sought to dismember Virginia and establish their own nal, and professional prominence as well as his VMI military mountain state. -

Battles of Mobile Bay, Petersburg, Memorialized on Civil War Forever Stamps Today Fourth of Five-Year Civil War Sesquicentennial Stamps Series Continues

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contacts July 30, 2014 VA: Freda Sauter 401-431-5401 [email protected] AL: Debbie Fetterly 954-298-1687 [email protected] National: Mark Saunders 202-268-6524 [email protected] usps.com/news To obtain high-resolution stamp images for media use, please email [email protected]. For broadcast quality video and audio, photo stills and other media resources, visit the USPS Newsroom. Battles of Mobile Bay, Petersburg, Memorialized on Civil War Forever Stamps Today Fourth of Five-Year Civil War Sesquicentennial Stamps Series Continues MOBILE, AL — Two of the most important events of the Civil War — the Battle of Mobile Bay (AL) and the siege at Petersburg, VA — were memorialized on Forever stamps today at the sites where these conflicts took place. One stamp depicts Admiral David G. Farragut’s fleet at the Battle of Mobile Bay (AL) on Aug. 5, 1864. The other stamp depicts the 22nd U.S. Colored Troops engaged in the June 15-18, 1864, assault on Petersburg, VA, at the beginning of the Petersburg Campaign. “The Civil War was one of the most intense chapters in our history, claiming the lives of more than 620,000 people,” said Postmaster General Patrick Donahoe in dedicating the Mobile Bay stamp. “Today, through events and programs held around the country, we’re helping citizens consider how their lives — and their own American experience — have been shaped by this period of history.” In Petersburg, Chief U.S. Postal Service Inspector Guy Cottrell dedicated the stamps just yards from the location of an underground explosion — that took place150 years ago today — which created a huge depression in the earth and led to the battle being named “Battle of the Crater.” Confederates — enraged by the sight of black soldiers — killed many soldiers trapped in the crater attempting to surrender. -

Educator Resource and Activity Guide

Educator Resource and Activity Guide introduction The Gulf Islands National Seashore is a protected region of barrier islands along the Gulf of Mexico and features historic resources and recreational opportunities spanning a 12-unit park in Florida and Mississippi. The Mississippi section encompasses Cat Island, Petit Bois Island, Horn Island, East and West Ship Islands, and the Davis Bayou area. Barrier islands, long and narrow islands made up of sand deposits created by waves and currents, run parallel to the coast line and serve to protect the coast from erosion. They also provide refuge for wildlife by harboring their habitats. From sandy-white beaches to wildlife sanctuaries, Mississippi’s wilderness shore is a natural and historic treasure. This guide provides an introduction to Ship Island, including important people, places, and events, and also features sample activities for usage in elementary, middle and high school classrooms. about the documentary The Gulf Islands: Mississippi’s Wilderness Shore is a Mississippi Public Broadcasting production showcasing the natural beauty of The Gulf Islands National Seashore Park, specifically the barrier islands in Mississippi – Cat Island, East and West Ship Islands, Horn Island, and Petit Bois Island – and the Davis Bayou area in Ocean Springs. The Gulf Islands National Seashore Park stretches 160 miles from Cat Island to the Okaloosa area near Fort Walton, Florida. The Gulf Islands documentary presents the islands’ history, natural significance, their role to protect Mississippi’s coast from hurricanes and the efforts to further protect and restore them. horn island in mississippi -2- ship island people n THE HISTORY -3- Ship Island, Mississippi has served as a crossroads through 300 years of American history. -

Library Inventory 2014.Xlsx

Last Updated 1/14/15 Jefferson County Historical Commission Library Inventory Classification Author ‐ Last Name Author ‐ First Name Book Title 976.4 Hoyt Edwin Alamo 358.4 Gregory Barry Airborne Warfare 1918‐1945 917.64 Foster Nancy Haston Alamo and Other Texas Missions to Remember 976.4 Groneman Bill Alamo Defenders 976.4 Groneman Bill Alamo Defenders 976.4 Templeton R. L. Alamo Soldier 976.4 Levy Janey Alamo: A Primary Source 940.3 Hoobler Dorothy Album of World War I 940.54 Jablonski Edward America in the Air War 940.53 Sulzberger C. L. American Heritage Picture 940.54 Sulzbergere C. L. American Hertiage Picture History of WW II 976.4 Watt Tula Townsend American Legion Auxiliary‐Dept. of Texas‐A History 1920‐1940 398.2 Brewer J. Mason American Negro Folklore 913.03 Cohen Daniel Ancient Monuments and How They Were Built 688.728 Godel Howard Antique Toy Trains 581.2 Stutzenbaker Charles Aquatic & Wetland Plants of the Western Gulf Coast 9*30.1 Fradin Dennis B. Archaeology 913 Schmandt‐Besserat Denise Archaeology 930.1 McIntosh Jane Archeology 930.1 Archeology 358.4 Nevin David Architects of Air Power 355.8 Coggins Jack Arms and Equipment of Civil War 355.1 Rosignoli Guido Army Badges & Insignia of World War 2 ‐ Book 1 355.1 Rosignoli Guido Army Badges & Insignia of World War 2 ‐ Book 2 355.1 Mollo Andrew Army Uniforms of World War 2 358.4 Weeks John Assault From the Sky 976.4 Carter Kathryn At the Battle of San Jacinto 911.73 Jackson Kenneth Atlas of American History 912.7 National Geographic Atlas of Natural America 976.4 Emery Emma Wilson Aunt Puss and Others 940.54 B‐17s Over Berlin 976.4 McDonald Archie Back Then: Simple Pleasures 976.4 Sitton Thad Backwoodsmen 973.7 McPherson James Battle Cry of Freedom Last Updated 1/14/15 Jefferson County Historical Commission Library Inventory Classification Author ‐ Last Name Author ‐ First Name Book Title 973.7 McPherson James Battle Cry of Freedom 973.7 McWhiney Grady Battle in the Wilderness 940.54 Goolrick William K. -

The Vulnerability of the Union War Effort to Naval Attacks at the Beginning of the US Civil War David G. Surdam

The Vulnerability of the Union War Effort to Naval Attacks at the Beginning of the US Civil War David G. Surdam The Confederate warship Virginia's short-lived triumph in March 1862 triggered a latent fear among some northerners, perhaps exemplified by Secretary of War Edwin Stanton's fit of panic. Upon hearing of the ironclad warship Virginia's successful sortie and apparent invulnerability against a northern fleet anchored in Hampton Roads off the southern Virginia coast, Stanton feared that the ironclad would destroy the remainder of the Union fleet there and scuttle General George McClellan's campaign against Richmond. He further feared that the ironclad would then steam up the Atlantic coast and wreak havoc upon northern ports, and he warned New York officials to block the entrances to the port. Confederate Secretary of the Navy Stephen Mallory hoped for this very result. Virginia's dubious seaworthiness and the Federal warship Monitor squelched Mallory's hopes and allayed Stanton's fears. Prior to Virginia's attack, northern nerves were upset by the Trent incident and the attendant possibility of British naval attacks.1 Virginia's failure to fulfill the Confederacy's hopes should not disguise the unease northerners felt about potential naval attacks. Northerners certainly were familiar with the effects of naval attacks: the War of 1812 was reminder enough. Was the northern war effort vulnerable to naval attacks? Was it important that the Federal navy prevented the nascent Confederate navy or the powerful British navy from attacking northern ports? The vulnerability or invulnerability of the northern war effort to naval attacks has received little attention from historians, possibly because Confederate naval attacks seemed unlikely and because the Trent incident ended quietly.