Performing the Novel: Vocal Poetics of Novelistic Discourse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jeudi 8 Juin 2017 Hôtel Ambassador

ALDE Hôtel Ambassador jeudi 8 juin 2017 Expert Thierry Bodin Syndicat Français des Experts Professionnels en Œuvres d’Art Les Autographes 45, rue de l’Abbé Grégoire 75006 Paris Tél. 01 45 48 25 31 - Facs 01 45 48 92 67 [email protected] Arts et Littérature nos 1 à 261 Histoire et Sciences nos 262 à 423 Exposition privée chez l’expert Uniquement sur rendez-vous préalable Exposition publique à l’ Hôtel Ambassador le jeudi 8 juin de 10 heures à midi Conditions générales de vente consultables sur www.alde.fr Frais de vente : 22 %T.T.C. Abréviations : L.A.S. ou P.A.S. : lettre ou pièce autographe signée L.S. ou P.S. : lettre ou pièce signée (texte d’une autre main ou dactylographié) L.A. ou P.A. : lettre ou pièce autographe non signée En 1re de couverture no 96 : [André DUNOYER DE SEGONZAC]. Ensemble d’environ 50 documents imprimés ou dactylographiés. En 4e de couverture no 193 : Georges PEREC. 35 L.A.S. (dont 6 avec dessins) et 24 L.S. 1959-1968, à son ami Roger Kleman. ALDE Maison de ventes spécialisée Livres-Autographes-Monnaies Lettres & Manuscrits autographes Vente aux enchères publiques Jeudi 8 juin 2017 à 14 h 00 Hôtel Ambassador Salon Mogador 16, boulevard Haussmann 75009 Paris Tél. : 01 44 83 40 40 Commissaire-priseur Jérôme Delcamp EALDE Maison de ventes aux enchères 1, rue de Fleurus 75006 Paris Tél. 01 45 49 09 24 - Facs. 01 45 49 09 30 - www.alde.fr Agrément n°-2006-583 1 1 3 3 Arts et Littérature 1. -

Herminie a Performer's Guide to Hector Berlioz's Prix De Rome Cantata Rosella Lucille Ewing Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2009 Herminie a performer's guide to Hector Berlioz's Prix de Rome cantata Rosella Lucille Ewing Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Ewing, Rosella Lucille, "Herminie a performer's guide to Hector Berlioz's Prix de Rome cantata" (2009). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2043. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2043 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. HERMINIE A PERFORMER’S GUIDE TO HECTOR BERLIOZ’S PRIX DE ROME CANTATA A Written Document Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music and Dramatic Arts by Rosella Ewing B.A. The University of the South, 1997 M.M. Westminster Choir College of Rider University, 1999 December 2009 DEDICATION I wish to dedicate this document and my Lecture-Recital to my parents, Ward and Jenny. Without their unfailing love, support, and nagging, this degree and my career would never have been possible. I also wish to dedicate this document to my beloved teacher, Patricia O’Neill. You are my mentor, my guide, my Yoda; you are the voice in my head helping me be a better teacher and singer. -

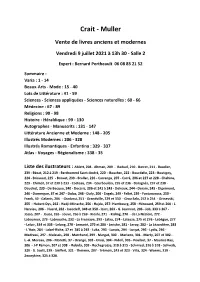

Crait - Muller

Crait - Muller Vente de livres anciens et modernes Vendredi 9 juillet 2021 à 13h 30 - Salle 2 Expert : Bernard Portheault 06 08 83 21 52 Sommaire : Varia : 1 - 14 Beaux-Arts - Mode : 15 - 40 Lots de Littérature : 41 - 59 Sciences - Sciences appliquées - Sciences naturelles : 60 - 66 Médecine : 67 - 89 Religions : 90 - 98 Histoire - Héraldique : 99 - 130 Autographes - Manuscrits : 131 - 147 Littérature Ancienne et Moderne : 148 - 205 Illustrés Modernes : 206 - 328 Illustrés Romantiques - Enfantina : 329 - 337 Atlas - Voyages - Régionalisme : 338 - 35 Liste des ilustrateurs : Ablett, 208 - Altman, 209 - Baduel, 210 - Barret, 211 - Baudier, 239 - Bécat, 212 à 219 - Berthommé Saint-André, 220 - Boucher, 222 - Bourdelle, 223 - Boutigny, 224 - Brissaud, 225 - Brouet, 239 - Bruller, 226 - Carrange, 207 - Carré, 206 et 227 et 228 - Chahine, 229 - Chimot, 37 et 230 à 233 - Cocteau, 234 - Courbouleix, 235 et 236 - Daragnès, 237 et 238 - Dauchot, 239 - De Becque, 240 - Decaris, 206 et 241 à 243 - Delvaux, 244 - Derain, 245 - Dignimont, 246 - Domergue, 37 et 247 - Dulac, 248 - Dufy, 206 - Engels, 249 - Falké, 239 - Fontanarosa, 250 - Frank, 40 - Galanis, 206 - Gradassi, 251 - Grandville, 329 et 330 - Grau Sala, 252 à 254 - Grinevski, 255 - Habert-Dys, 262 - Hadji-Minache, 256 - Hajdu, 257- Hambourg, 258 - Hérouard, 259 et 260 - L. Hervieu, 206 - Huard, 262 - Iacocleff, 348 et 350 - Icart, 263 - G. Jeanniot, 206 - Job, 333 à 367 - Josso, 207 - Jouas, 265 - Jouve, 266 à 269 - Kioshi, 271 - Kisling, 270 - de La Nézière, 272 - Laboureur, 273 - Labrouche, 232 - La Fresnaye, 293 - Lalau, 274 - Lalauze, 275 et 276 - Lebègue, 277 - Leloir, 334 et 335 - Lelong, 278 - Lemarié, 279 et 280 - Leriche, 281 - Leroy, 282 - La Lézardière, 283 - L’Hoir, 284 - Lobel-Riche, 37 et 285 à 292 - Luka, 293 - Lunois, 294 - Lurçat, 295 - Lydis, 296 - Madrassi, 297 - Malassis, 298 - Marchand, 299 - Margat, 300 - Mariano, 301 - Marty, 207 et 302 - L.-A. -

Lully's Psyche (1671) and Locke's Psyche (1675)

LULLY'S PSYCHE (1671) AND LOCKE'S PSYCHE (1675) CONTRASTING NATIONAL APPROACHES TO MUSICAL TRAGEDY IN THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ' •• by HELEN LLOY WIESE B.A. (Special) The University of Alberta, 1980 B. Mus., The University of Calgary, 1989 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS • in.. • THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES SCHOOL OF MUSIC We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA October, 1991 © Helen Hoy Wiese, 1991 In presenting this hesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. (Signature) Department of Kos'iC The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date ~7 Ocf I DE-6 (2/68) ABSTRACT The English semi-opera, Psyche (1675), written by Thomas Shadwell, with music by Matthew Locke, was thought at the time of its performance to be a mere copy of Psyche (1671), a French tragedie-ballet by Moli&re, Pierre Corneille, and Philippe Quinault, with music by Jean- Baptiste Lully. This view, accompanied by a certain attitude that the French version was far superior to the English, continued well into the twentieth century. -

Télécharger Un Extrait

TABLE DES MATIÈRES Avant-propos ..........................................................................................................................................................7 Introduction – Questionnements et contextes ................................................................................13 1. Prologues – Le Roi a la préséance ..................................................................................................49 2. Cadmus et Hermione – L’invention de la tragédie en musique ..........................................71 3. Alceste – La genèse d’un style..............................................................................................................95 4. Thésée – Omnia vincunt amor… gloriaque ......................................................................................123 5. Atys – L’accord tragique de la lyre..................................................................................................155 6. Isis – Au delà de la tragédie ..............................................................................................................179 7. Proserpine – Une prudence féministe dans un monde patriarcal ..................................207 8. Persée – Des rivalités de toutes parts ............................................................................................229 9. Phaéton – L’orgueil précède la chute ............................................................................................249 10. Amadis – Nouvelles directions et thèmes familiers..............................................................267 -

The Challenges of Opera Direction

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-2000 The challenges of opera direction Dean Frederick Lundquist University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Lundquist, Dean Frederick, "The challenges of opera direction" (2000). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 1167. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/wzqe-ihk0 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substarxfard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Death in the Comedy of Molière

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 8-2003 Dying for a laugh : death in the comedy of Molière Clara Noëlle Wynne Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Recommended Citation Wynne, Clara Noëlle, "Dying for a laugh : death in the comedy of Molière. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2003. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/5211 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Clara Noëlle Wynne entitled "Dying for a laugh : death in the comedy of Molière." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Modern Foreign Languages. Sal DiMaria, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Clara Noelle Wynne entitled "Dying for a Laugh: Death in the Comedy of Moliere". I have examined the final paper copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Modern Foreign Languages. -

De Philippe Quinault, Dramaturge Du

LES STRATÉGIESIWÉTORIQUES DE PHILIPPEQUINAULT DANS SES ÉP~TRESDÉDICATOIRES, DANSLES PROLOGUES DE SES OPÉRAS ET DANS SA TRAGÉDIE LYRIQUE, THÉSEE Par SHANNON DIANE PURVES-SMTK Thèse soumise à la "Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research" comme exigence panielle en vue de l'obtention de la maîtrise ès arts (Master of Arts) Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario 18 janvier 2000 O Copyright Shannon Purves-Smith, 2000 National Library Bibliothèque nationale ($.m of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Canada Canada Yaur hh? Votre reldmce Our Ma Noire teUrence The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or seU reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la fome de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownershp of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imphmés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Cette thèse étudie l'usage des stratégies rhétoriques de Philippe Quinault, dramaturge du XWe siècle, dans trois genres: l'épître dédicatoire, le prologue, ou divertissement dramatique qui précède un opéra, et le livret d'une tragédie lyrique (ou opéra). -

TWO HUNDRED and FIFTY YEARS of the OPERA (1669-1919) Downloaded from by J.-G

TWO HUNDRED AND FIFTY YEARS OF THE OPERA (1669-1919) Downloaded from By J.-G. PROD'HOMME " A NNO 1669."—This hybrid inscription, which may be read /-% above the curtain of the Acadimie national* de musique, re- minds the spectators that our foremost lyric stage is a crea- http://mq.oxfordjournals.org/ tion of Louis XTV, like its elder sisters the academies of painting and sculpture, of dancing, of inscriptions and belles-lettres, of sciences, and the Academy of Architecture, its junior. In turn royal, national, imperial, following the changes of government, it has survived them all, having had within itself its revolutions, musical or otherwise, its periods of glory or decadence, its golden years or seasons of mediocrity; now in the lead of the musical movement, and again constrained to float with the currents of at Indiana University Library on March 16, 2015 foreign influence; but always inviting the envy of some elements and the curiosity of others. Celebrating its two hundred and fiftieth anniversary, what other lyric stage in the world can boast an equal longevity? Un- questionably, the Paris Opera was not the first in Europe to be opened to the public. Before it, Venice had had opera houses accessible to the bourgeois and the general public; but,.while their existence is no more than a memory, the Parisian "grand opera," surviving all revolutions in politics or of taste, has continued— sometimes, as it were, against its will—an unbroken tradition which, despite its imperfections, is not wanting in grandeur. The history of the Opera presents a striking parallel to that of France itself, and at times to that of Europe. -

The World of Lully

Cedille Records CDR 90000 043 The World of Lully Music of Jean-Baptiste Lully and his Followers CHICAGO BAROQUE ENSEMBLE WITH PATRICE MICHAELS BEDI, SOPRANO DDD Absolutely Digital CDR 90000 043 THE WORLD OF JEAN-BAPTISTE LULLY (1632-1687) Lully: Première Divertissement (15:09) 1 Ouverture from Armide (2:29) 2 Air from Persée (1:18) 3 Serenade from Ballet des plaisirs (4:31) 4 Air from Phaeton (0:50) 5 Chanson contre les jaloux from Ballet de l’amour Malade (2:23) 6 Minuet from Armide (0:44) 7 Air: Pauvres amants from Le Sicilen (2:48) Jean-Féry Rebel: Le Tombeau de Monsieur Lully (14:01) 8 Lentement (2:39) 9 Vif (2:03) 10 Lentement (2:43) 11 Vivement (3:50) 12 Les Regrets (2:46) Lully: Seconde Divertissement (9:34) 13 Menuet from Alceste (0:58) 14 C’est la saison d’aimer from Alceste (1:32) 15 Recit: Suivons de si douces loix from Ballet d’Alcidiane (1:48) 16 Gavotte from Amadis (1:16) 17 Gigue – Les Plaisirs nous suivent from Amadis (3:56) Lully, arr. Jean d’Anglebert: Pièces de clavecin (7:35) 18 Ouverture de la Mascarade (3:53) 19 Les songes agréables (1:54) 20 Gigue (1:44) 21 Lully: Plainte de Cloris from Le Grand Divertissement Royal de Versailles (5:26) 22 Lully: Galliarde from Trios pour le coucher du roi (3:07) 23 Marin Marais: Tombeau de Lully from Second livre de pièces de violes (6:21) Lully: Armide, Tragedie lyrique (selections) (15:50) 24 Recit: Enfin il est en ma puissance (3:18) 25 Air: Venez, venez seconder mes desirs (1:10) 26 Air (0:53) 27 Passacaille (arr. -

THE CONCERT of NATIONS: MUSIC, POLITICAL THOUGHT and DIPLOMACY in EUROPE, 1600S-1800S

THE CONCERT OF NATIONS: MUSIC, POLITICAL THOUGHT AND DIPLOMACY IN EUROPE, 1600s-1800s A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Damien Gérard Mahiet August 2011 © 2011 Damien Gérard Mahiet THE CONCERT OF NATIONS: MUSIC, POLITICAL THOUGHT AND DIPLOMACY IN EUROPE, 1600s-1800s Damien Gérard Mahiet, Ph. D. Cornell University 2011 Musical category, political concept, and political myth, the Concert of nations emerged within 16th- and 17th-century court culture. While the phrase may not have entered the political vocabulary before the end of the 18th century, the representation of nations in sonorous and visual ensembles is contemporary to the institution of the modern state and the first developments of the international system. As a musical category, the Concert of nations encompasses various genres— ballet, dance suite, opera, and symphony. It engages musicians in making commonplaces, converting ad hoc representations into shared realities, and uses multivalent forms that imply, rather than articulate political meaning. The Nutcracker, the ballet by Tchaikovsky, Vsevolozhsky, Petipa and Ivanov, illustrates the playful re- composition of semiotic systems and political thought within a work; the music of the battle scene (Act I) sets into question the equating of harmony with peace, even while the ballet des nations (Act II) culminates in a conventional choreography of international concord (Chapter I). Chapter II similarly demonstrates how composers and librettists directly contributed to the conceptual elaboration of the Concert of nations. Two works, composed near the close of the War of Polish Succession (1733-38), illustrate opposite constructions of national character and conflict resolution: Schleicht, spielende Wellen, und murmelt gelinde (BWV 206) by Johann Sebastian Bach (librettist unknown), and Les Sauvages by Jean-Philippe Rameau and Louis Fuzelier. -

Wendy Heller, Music in the Baroque Chapter 7: Power and Pleasure in the Court of Louis XIV Study Guide

Wendy Heller, Music in the Baroque Chapter 7: Power and Pleasure in the Court of Louis XIV Study Guide Anthology Repertory 13. Jean-Baptiste Lully, Armide, Act 5, scene 5: Le perfide Renaud me fuit Repertory Discussed: Fig. 7.3 Michel Lambert, “Par mes chants” Ex. 7.1 Jean Henry d’Anglebert, Pièces de clavessin (1689): Chaconne de Phaeton de Mr. De Lully E. 7.2 J Jean-Baptiste Lully, Armide: Act 2, scene 5 Ex. 7.3 Marc-Antoine Charpentier: Medée, Act 4, scene 7 General • Ballet de la Nuit (1653) featuring the young Louis XIV as example of political use of arts. • Contrast between the young and old Louis XIV Centralization of the Arts under the Bourbon Role • Organization of music at the French court o Musique de la chambre (chamber musicians) o 24 Violons du Roi o Grand Écurie – outdoor music • Primary institutions for the arts o Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture o Académie dde danse (1661) and Académie d’Opéra (1669) combine to become the Academie Royale de Musique (1671) • Building and establishment of Versailles as residence for Louis XIV and distraction for nobles What’s so French About French Music? • Relatively insular style, but one that was recognizably French when exported • Tends to be less chromatic and less goal-oriented than German and Italian music • Adapts the distinctive features of the French language—resulting in rhythmic plasticity and frequent changes between duple and triple in vocal music • Importance of court and theatrical dance in court life; also instrumental music • Highly developed system of ornamentation or agréements that was obligatory not optional • Texture—popularity of style brisé or broken style in keyboard and lute music • Special attention to varied instrumental color, both in sacred and secular music.