Death in the Comedy of Molière

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

177 Mental Toughness Secrets of the World Class

177 MENTAL TOUGHNESS SECRETS OF THE WORLD CLASS 177 MENTAL TOUGHNESS SECRETS OF THE WORLD CLASS The Thought Processes, Habits And Philosophies Of The Great Ones Steve Siebold 177 MENTAL TOUGHNESS SECRETS OF THE WORLD CLASS 177 MENTAL TOUGHNESS SECRETS OF THE WORLD CLASS The Thought Processes, Habits And Philosophies Of The Great Ones Steve Siebold Published by London House www.londonhousepress.com © 2005 by Steve Siebold All Rights Reserved. Printed in Hong Kong. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. Ordering Information To order additional copies please visit www.mentaltoughnesssecrets.com or visit the Gove Siebold Group, Inc. at www.govesiebold.com. ISBN: 0-9755003-0-9 Credits Editor: Gina Carroll www.inkwithimpact.com Jacket and Book design by Sheila Laughlin 177 MENTAL TOUGHNESS SECRETS OF THE WORLD CLASS DEDICATION This book is dedicated to the three most important people in my life, for their never-ending love, support and encouragement in the realization of my goals and dreams. Dawn Andrews Siebold, my beautiful, loving wife of almost 20 years. You are my soul mate and best friend. I feel best about me when I’m with you. We’ve come a long way since sub-man. I love you. Walter and Dolores Siebold, my parents, for being the most loving and supporting parents any kid could ask for. Thanks for everything you’ve done for me. -

Jeudi 8 Juin 2017 Hôtel Ambassador

ALDE Hôtel Ambassador jeudi 8 juin 2017 Expert Thierry Bodin Syndicat Français des Experts Professionnels en Œuvres d’Art Les Autographes 45, rue de l’Abbé Grégoire 75006 Paris Tél. 01 45 48 25 31 - Facs 01 45 48 92 67 [email protected] Arts et Littérature nos 1 à 261 Histoire et Sciences nos 262 à 423 Exposition privée chez l’expert Uniquement sur rendez-vous préalable Exposition publique à l’ Hôtel Ambassador le jeudi 8 juin de 10 heures à midi Conditions générales de vente consultables sur www.alde.fr Frais de vente : 22 %T.T.C. Abréviations : L.A.S. ou P.A.S. : lettre ou pièce autographe signée L.S. ou P.S. : lettre ou pièce signée (texte d’une autre main ou dactylographié) L.A. ou P.A. : lettre ou pièce autographe non signée En 1re de couverture no 96 : [André DUNOYER DE SEGONZAC]. Ensemble d’environ 50 documents imprimés ou dactylographiés. En 4e de couverture no 193 : Georges PEREC. 35 L.A.S. (dont 6 avec dessins) et 24 L.S. 1959-1968, à son ami Roger Kleman. ALDE Maison de ventes spécialisée Livres-Autographes-Monnaies Lettres & Manuscrits autographes Vente aux enchères publiques Jeudi 8 juin 2017 à 14 h 00 Hôtel Ambassador Salon Mogador 16, boulevard Haussmann 75009 Paris Tél. : 01 44 83 40 40 Commissaire-priseur Jérôme Delcamp EALDE Maison de ventes aux enchères 1, rue de Fleurus 75006 Paris Tél. 01 45 49 09 24 - Facs. 01 45 49 09 30 - www.alde.fr Agrément n°-2006-583 1 1 3 3 Arts et Littérature 1. -

Organizing Books and Did This Process, I Discovered That Two of Them Had a Really Yucky Feeling to Them

Jennifer Hofmann Inspired Home Office © 2014 This graphic is intentionally small to save your printer ink.:) 1 Inspired Home Office: The Book First edition Copyright 2014 Jennifer E. Hofmann, Inspired Home Office All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recorded, or otherwise without written permission by the author. This publication contains the opinion and ideas of the author. It is intended to provide helpful and informative material on the subject matter covered, and is offered with the understanding that the author is not engaged in rendering professional services in this publication. If the reader requires legal, financial or other professional assistance or advice, a qualified professional should be consulted. No liability is assumed with respect to the use of the information contained herein. Although every precaution has been taken to produce a high quality, informative, and helpful book, the author makes no representation or warranties of any kind with regard to the completeness or accuracy of the contents of the book. The author specifically disclaims any responsibility for any liability, loss or risk, personal or otherwise, which is incurred as a consequence, directly or indirectly, from the use and application of any of the contents of this publication. Jennifer Hofmann Inspired Home Office 3705 Quinaby Rd NE Salem, OR 97303 www.inspiredhomeoffice.com 2 Table of Contents Introduction.................................................................................................................. -

Don Juan Entire First Folio

First Folio Teacher Curriculum Guide Don Juan by Molière translated, adapted and directed by Stephen Wadsworth January 24—March 19, 2006 First Folio Teacher Curriculum Guide Table of Contents Page Number Welcome to the Shakespeare Theatre Company’s production ofDon Juan by Molière! A Brief History of the Audience…………………….1 Each season, the Shakespeare Theatre Company About the Playwright presents five plays by William Shakespeare and other classic playwrights. The Education Department Molière’s Life………………….…………………………………3 continues to work to deepen understanding, Molière’s Theatre…….……………………………………….4 appreciation and connection to classic theatre in 17th•Century France……………………………………….6 learners of all ages. One approach is the publication of First Folio: Teacher Curriculum Guides. About the Play Synopsis of Don Juan…………………...………………..8 In the 2005•06 season, the Education Department Don Juan Timeline….……………………..…………..…..9 will publish First Folio: Teacher Curriculum Guides for Marriage & Family in 17th•Century our productions ofOthello, The Comedy of Errors, France…………………………………………………...10 Don Juan, The Persiansand Love’s Labor’s Lost. The Guides provide information and activities to help Splendid Defiance……………………….....................11 students form a personal connection to the play before attending the production at the Shakespeare Classroom Connections Theatre Company. First Folio guides are full of • Before the Performance……………………………13 material about the playwrights, their world and the Translation & Adaptation plays they penned. Also included are approaches to Censorship explore the plays and productions in the classroom Questioning Social Mores before and after the performance.First Folio is Playing Around on Your Girlfriend/ designed as a resource both for teachers and Boyfriend students. Commedia in Molière’s Plays The Shakespeare Theatre Company’s Education Department provides an array of School, • After the Performance………………………………14 Community, Training and Audience Enrichment Friends Don’t Let Friends.. -

Herminie a Performer's Guide to Hector Berlioz's Prix De Rome Cantata Rosella Lucille Ewing Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2009 Herminie a performer's guide to Hector Berlioz's Prix de Rome cantata Rosella Lucille Ewing Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Ewing, Rosella Lucille, "Herminie a performer's guide to Hector Berlioz's Prix de Rome cantata" (2009). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2043. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2043 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. HERMINIE A PERFORMER’S GUIDE TO HECTOR BERLIOZ’S PRIX DE ROME CANTATA A Written Document Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music and Dramatic Arts by Rosella Ewing B.A. The University of the South, 1997 M.M. Westminster Choir College of Rider University, 1999 December 2009 DEDICATION I wish to dedicate this document and my Lecture-Recital to my parents, Ward and Jenny. Without their unfailing love, support, and nagging, this degree and my career would never have been possible. I also wish to dedicate this document to my beloved teacher, Patricia O’Neill. You are my mentor, my guide, my Yoda; you are the voice in my head helping me be a better teacher and singer. -

~'7/P64~J Adviser Department of S Vie Languages and Literatures @ Copyright By

FREEDOM AND THE DON JUAN TRADITION IN SELECTED NARRATIVE POETIC WORKS AND THE STONE GUEST OF ALEXANDER PUSHKIN DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By James Goodman Connell, Jr., B.S., M.A., M.A. The Ohio State University 1973 Approved by ,r-~ ~'7/P64~j Adviser Department of S vie Languages and Literatures @ Copyright by James Goodman Connell, Jr. 1973 To my wife~ Julia Twomey Connell, in loving appreciation ii VITA September 21, 1939 Born - Adel, Georgia 1961 .•..••. B.S., United States Naval Academy, Annapolis, Maryland 1961-1965 Commissioned service, U.S. Navy 1965-1967 NDEA Title IV Fellow in Comparative Literature, The University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia 1967 ••••.•. M.A. (Comparative Literature), The University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia 1967-1970 NDFL Title VI Fellow in Russian, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1969 •.•••.• M.A. (Slavic Languages and Literatures), The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1970 .•...•. Assistant Tour Leader, The Ohio State University Russian Language Study Tour to the Soviet Union 1970-1971 Teaching Associate, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1971-1973 Assistant Professor of Modern Foreign Languages, Valdosta State College, Valdosta, Georgia FIELDS OF STUDY Major field: Russian Literature Studies in Old Russian Literature. Professor Mateja Matejic Studies in Eighteenth Century Russian Literature. Professor Frank R. Silbajoris Studies in Nineteenth Century Russian Literature. Professors Frank R. Silbajoris and Jerzy R. Krzyzanowski Studies in Twentieth Century Russian Literature and Soviet Literature. Professor Hongor Oulanoff Minor field: Polish Literature Studies in Polish Language and Literature. -

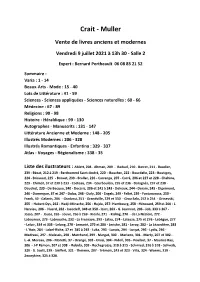

Crait - Muller

Crait - Muller Vente de livres anciens et modernes Vendredi 9 juillet 2021 à 13h 30 - Salle 2 Expert : Bernard Portheault 06 08 83 21 52 Sommaire : Varia : 1 - 14 Beaux-Arts - Mode : 15 - 40 Lots de Littérature : 41 - 59 Sciences - Sciences appliquées - Sciences naturelles : 60 - 66 Médecine : 67 - 89 Religions : 90 - 98 Histoire - Héraldique : 99 - 130 Autographes - Manuscrits : 131 - 147 Littérature Ancienne et Moderne : 148 - 205 Illustrés Modernes : 206 - 328 Illustrés Romantiques - Enfantina : 329 - 337 Atlas - Voyages - Régionalisme : 338 - 35 Liste des ilustrateurs : Ablett, 208 - Altman, 209 - Baduel, 210 - Barret, 211 - Baudier, 239 - Bécat, 212 à 219 - Berthommé Saint-André, 220 - Boucher, 222 - Bourdelle, 223 - Boutigny, 224 - Brissaud, 225 - Brouet, 239 - Bruller, 226 - Carrange, 207 - Carré, 206 et 227 et 228 - Chahine, 229 - Chimot, 37 et 230 à 233 - Cocteau, 234 - Courbouleix, 235 et 236 - Daragnès, 237 et 238 - Dauchot, 239 - De Becque, 240 - Decaris, 206 et 241 à 243 - Delvaux, 244 - Derain, 245 - Dignimont, 246 - Domergue, 37 et 247 - Dulac, 248 - Dufy, 206 - Engels, 249 - Falké, 239 - Fontanarosa, 250 - Frank, 40 - Galanis, 206 - Gradassi, 251 - Grandville, 329 et 330 - Grau Sala, 252 à 254 - Grinevski, 255 - Habert-Dys, 262 - Hadji-Minache, 256 - Hajdu, 257- Hambourg, 258 - Hérouard, 259 et 260 - L. Hervieu, 206 - Huard, 262 - Iacocleff, 348 et 350 - Icart, 263 - G. Jeanniot, 206 - Job, 333 à 367 - Josso, 207 - Jouas, 265 - Jouve, 266 à 269 - Kioshi, 271 - Kisling, 270 - de La Nézière, 272 - Laboureur, 273 - Labrouche, 232 - La Fresnaye, 293 - Lalau, 274 - Lalauze, 275 et 276 - Lebègue, 277 - Leloir, 334 et 335 - Lelong, 278 - Lemarié, 279 et 280 - Leriche, 281 - Leroy, 282 - La Lézardière, 283 - L’Hoir, 284 - Lobel-Riche, 37 et 285 à 292 - Luka, 293 - Lunois, 294 - Lurçat, 295 - Lydis, 296 - Madrassi, 297 - Malassis, 298 - Marchand, 299 - Margat, 300 - Mariano, 301 - Marty, 207 et 302 - L.-A. -

Desperate Housewives a Lot Goes on in the Strange Neighborhood of Wisteria Lane

Desperate Housewives A lot goes on in the strange neighborhood of Wisteria Lane. Sneak into the lives of five women: Susan, a single mother; Lynette, a woman desperately trying to b alance family and career; Gabrielle, an exmodel who has everything but a good m arriage; Bree, a perfect housewife with an imperfect relationship and Edie Britt , a real estate agent with a rocking love life. These are the famous five of Des perate Housewives, a primetime TV show. Get an insight into these popular charac ters with these Desperate Housewives quotes. Susan Yeah, well, my heart wants to hurt you, but I'm able to control myself! How would you feel if I used your child support payments for plastic surgery? Every time we went out for pizza you could have said, "Hey, I once killed a man. " Okay, yes I am closer to your father than I have been in the past, the bitter ha tred has now settled to a respectful disgust. Lynette Please hear me out this is important. Today I have a chance to join the human rac e for a few hours there are actual adults waiting for me with margaritas. Loo k, I'm in a dress, I have makeup on. We didn't exactly forget. It's just usually when the hostess dies, the party is off. And I love you because you find ways to compliment me when you could just say, " I told you so." Gabrielle I want a sexy little convertible! And I want to buy one, right now! Why are all rich men such jerks? The way I see it is that good friends support each other after something bad has happened, great friends act as if nothing has happened. -

The Element of Self-Interest in Moliã¨Re's Characterisation

, I 'l'HE ELm1ENT OF SELF-INTEREST IN MOLIERE I S CHp,RAC'rERISNI'ION THE ELEMENT OF SELF-INTEREST IN MOLIERE'S CHARAC'I'ERISA'I'ION by Bola Sodipo, B.A. '(Manches ter) A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMas'ter Uni vend ty October 1970 !-1ASTER OF ARTS (1970) Mcl!J:ASTER Ul'iilVERSITY (Romance Languages) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: The Element of Self-Interest in Moliere's Characterisation AUTHOR: Bola Sodipo, B.A. (Manches"ter) SUPERVISOR: Dr. G. A. Warner NUMBER OF PAGES: iv I 99. SCOPE AND CONTENTS: A discussion of the na"ture of self~in·- terest and an analysis of how Moliere exploits this them.ein the creation of his comic types. ii ACKNmvLEDGEMENT I should.like to express my sincere gratitude to Professor G. l"larner, who gave me invaluable help and guidance during the course of this study. Indeed, I am indebted to him for suggesting the psychological r drcnnatic and comic terms in which the element of self-interest is examined. iii TAB LEO F CON TEN T S Page INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER I THE PSYCHOLOGY OF SELF-INTEP~ST 9 CHAPTER II THE DR~1ATIC EXPLOITATION OF SELF-IN'l'EREST 34 CHAPTER III THE COMIC EXPLOITATION OF SELF-INTEREST 60 CONCLUSION 90 BIBLIOGRA.PHY 94 iv INTRODUCTION Self-·interest is defined ln t,he Concise Oxford Dic'tionary as being II actua'ted or absorbed in what one con- ceives to be 'for one's interests Ii. -

Pushing Boundaries with Don Giovanni.Pdf

Giovanni 2017 articles.qxp_Don Giovanni 2017 5/23/17 12:55 PM Page 1 B Y J U D I T H M A L A F R O N T E Pushing Boundaries with Don Giovanni any years ago, my solfège teacher told me about sneak- drama and bringing complexity and seriousness to all the charac- ing out of Paris on public transportation with the origi- ters. If Da Ponte knew Molière’s 1665 Dom Juan ou le Festin de nal manuscript of Don Giovanni wrapped in brown paper pierre, it was only in the heavily censored version published in 1682. Mon her lap. Annette Dieudonné—composer, translator, key- Director Stephen Wadsworth, whose new translation of Molière’s boardist, and musicologist—had been a librarian at the Paris Con- Dom Juan is soon to be published by Smith and Kraus, finds the servatoire during World War II, and just before the German title character sexy and dangerous because of his mind and his free- occupation, she took many priceless manuscripts out to the coun- thinking. “Molière aimed this anarchic force at the hypocrisy of try and buried them to avoid confiscation or destruction. (She church and state; his Don Juan observed the world with a shocking, neglected to mention that she had been awarded the Légion cleansing rationality.” No wonder the censors ordered revisions d’honneur for this work.) after only one performance. It was never about sex. (Molière’s Don Another woman who saved Don Giovanni was Pauline Viardot, Juan even seduces a nun.) More upsetting to the establishment was the legendary 19th-century diva, who had purchased this same what Wadsworth calls Giovanni’s “rational, logical, unapologetic manuscript from a dealer who had acquired it from Mozart’s world-view,” skeptical and anti-religious. -

Lettheriverrun Ebook.Pdf

How God Used Ordinary People to Do Extraordinary Things Dan Scott, with Austin & Tiffany Cagle This book is lovingly dedicated to the first generation of Christ Church, who, under the leadership of L.H. and Montelle Hardwick, took the time to build a life-giving community that has changed the world. Their vision lives. © All contents of this manuscript are protected by copyrights owned by Epiclesis, Inc., 1717 Park Terrace Lane, Nolensville, TN 37135 and may not be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher 3 Table of Contents .............................................................. 4 Introduction ...................................................................... 5 A Visitor Blows Up Our Dam ........................................... 9 The River Starts Flowing ............................................... 26 Telling Money Where to Flow ........................................ 33 Currency Really Is a Current ......................................... 43 A Russian River Flows Through .................................... 57 Going With the Flow ....................................................... 74 A River Has Banks ........................................................ 87 Dancing with the River ................................................ 104 Keepers of the Spring ................................................... 117 Finding the Source ....................................................... 125 Three Streams Converge .............................................. 133 The River Keeps -

Lully's Psyche (1671) and Locke's Psyche (1675)

LULLY'S PSYCHE (1671) AND LOCKE'S PSYCHE (1675) CONTRASTING NATIONAL APPROACHES TO MUSICAL TRAGEDY IN THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ' •• by HELEN LLOY WIESE B.A. (Special) The University of Alberta, 1980 B. Mus., The University of Calgary, 1989 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS • in.. • THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES SCHOOL OF MUSIC We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA October, 1991 © Helen Hoy Wiese, 1991 In presenting this hesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. (Signature) Department of Kos'iC The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date ~7 Ocf I DE-6 (2/68) ABSTRACT The English semi-opera, Psyche (1675), written by Thomas Shadwell, with music by Matthew Locke, was thought at the time of its performance to be a mere copy of Psyche (1671), a French tragedie-ballet by Moli&re, Pierre Corneille, and Philippe Quinault, with music by Jean- Baptiste Lully. This view, accompanied by a certain attitude that the French version was far superior to the English, continued well into the twentieth century.