Innovation Across Time and Space: Advantage New Companies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pfizer's Bourla

No. 3985 December 13, 2019 line success and business development. “In the next two years, we need to see how the pipeline is delivering,” he said. Bourla has been outspoken that when it comes to business development, he doesn’t see a mega-merger on the hori- zon. Instead, he said he is looking to bring in mid-stage clinical development assets to complement the internal pipeline. It sounds like investors can expect the company to be active on the business development front within those guard- rails. “I want to double it,” he said of the pipeline, which includes 92 projects right now. “And, we are going to double it by bringing in a lot of innovation to comple- ment what we distribute.” The company is focusing business de- velopment on six core therapeutic areas Pfizer’s Bourla: “I Think We Forgot as well, but Bourla indicated the company will be actively building out those areas both through internal investment and What It Looks Like To Grow” external collaboration. “We’re going to be JESSICA MERRILL [email protected] active because Pfizer is a very big plane and it cannot fly with one engine,” he said. fizer Inc. CEO Albert Bourla took in July it will merge the Upjohn business Bourla highlighted Pfizer’s recent acqui- over the top leadership spot from with Mylan NV to form a new generic drug sition of the cancer specialist Array Bio- PIan Read a year ago, but has quickly company to be called Viatris GMBH. Pharma for $11.4bn as an example of the executed on big changes poised to make The resulting Pfizer will be significantly kinds of deals the company will be pursu- Pfizer significantly smaller and faster smaller, with a 2020 annual revenue base ing. -

Health Industry Business Communications Council

Health Industry Business Communications Council Registered Labelers: Accredited Auto-ID Labeling Standards Argentina New MedTek Devices Pty Ltd Oxavita SRL Norseld Pty Ltd. Novadien Healthcare Pty Ltd The following companies Odontit S.A. (and/or their subsidiaries/ PAMPAMED S.R.L. Numedico Technologies Pty Ltd divisions) have applied PATEJIM SRL Opto Global Pty. Ltd. for a Labeler Identification Orthocell Limited Code (LIC) assignment with Austria Prolotus Technologies Pty Ltd HIBCC*. By doing so, they afreeze GmbH Red Milawa Pty Ltd dba Magic Mobility have demonstrated their AMI GmbH SDI Limited commitment to patient safety Bender Medsystems GmbH Signostics Ltd. and logistical efficiency for BHS Technologies GmbH Sirtex Medical Pty Ltd their customers, the industry Metasys Medizintechnik GmbH Smith & Nephew Surgical Pty. Ltd. and the public at large. PAA Laboratories GmbH Staminalift International Limited Safersonic Medizinprodukte Handels The Pipette Company Pty. Ltd. Any organization that is GmbH Thermo Electron Corporation interested in using the HIBC W & H Dentalwerk Burmoos GmbH Vush Pty Ltd uniform labeling system may apply for the assignment of VUSH STIMULATION Australia one or more LICs. William A Cook Australia Pty. Ltd. Adv. Surgical Design & Manufacture, Ltd. Last updated 9-21-2021 AirPhysio Pty Ltd Belgium Annalise-AI Pty Ltd 3M Europe Apollo Medical Imaging Technology Pty Advanced Medical Diagnostics SA/NV Ltd Analis SA/NV Benra Pty Ltd dba Gelflex Laboratories Baxter World Trade Bioclone Australia Pty. Ltd. Bio-Rad RSL Candelis, Inc. Bio-Rad Lab Inc Clinical Diag. Group DePuy Australia Pty. Ltd. Biosource Europe SA For more information, please dorsaVi Ltd Cilag NV contact the HIBCC office at: EC Certification Service GmbH Coris Bioconcept Fink Engineering Pty Ltd Fuji Hunt Photographic Chemicals NV 2525 E. -

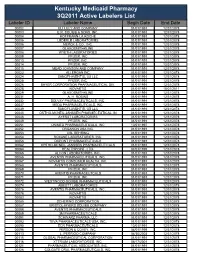

Active Labelers List Labeler ID Labeler Name Begin Date End Date 00002 ELI LILLY and COMPANY 01/01/1991 12/31/2078 00003 E.R

Kentucky Medicaid Pharmacy 3Q2011 Active Labelers List Labeler ID Labeler Name Begin Date End Date 00002 ELI LILLY AND COMPANY 01/01/1991 12/31/2078 00003 E.R. SQUIBB & SONS, INC. 01/01/1991 12/31/2078 00004 HOFFMANN-LA ROCHE 01/01/1991 12/31/2078 00005 LEDERLE LABORATORIES 01/01/1991 12/31/2078 00006 MERCK & CO., INC. 01/01/1991 12/31/2078 00007 GLAXOSMITHKLINE 01/01/1991 12/31/2078 00008 WYETH LABORATORIES 01/01/1991 12/31/2078 00009 PFIZER, INC 01/01/1991 12/31/2078 00013 PFIZER, INC. 01/01/1991 12/31/2078 00014 PFIZER, INC 01/01/1991 12/31/2078 00015 MEAD JOHNSON AND COMPANY 01/01/1991 12/31/2078 00023 ALLERGAN INC 01/01/1991 12/31/2078 00024 SANOFI-AVENTIS, US LLC 01/01/1991 12/31/2078 00025 PFIZER, INC. 01/01/1991 12/31/2078 00026 BAYER CORPORATION PHARMACEUTICAL DIV. 01/01/1991 12/31/2078 00028 NOVARTIS 01/01/1991 10/01/2011 00029 GLAXOSMITHKLINE 01/01/1991 12/31/2078 00031 A. H. ROBINS 01/01/1991 12/31/2078 00032 SOLVAY PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. 01/01/1991 12/31/2078 00037 MEDA PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. 01/01/1991 12/31/2078 00039 SANOFI-AVENTIS, US LLC 01/01/1991 12/31/2078 00045 ORTHO-MCNEIL-JANSSEN PHARMECEUTICAL, IN 01/01/1991 12/31/2078 00046 AYERST LABORATORIES 01/01/1991 12/31/2078 00049 PFIZER, INC 01/01/1991 12/31/2078 00051 UNIMED PHARMACEUTICALS, INC 10/01/1997 12/31/2078 00052 ORGANON USA INC. -

PFIZER INC. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K (Mark One) ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2019 ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission file number 1-3619 PFIZER INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 13-5315170 (State or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) (I.R.S. Employer Identification Number) 235 East 42nd Street, New York, New York 10017 (Address of principal executive offices) (zip code) (212) 733-2323 (Registrant’s telephone number, including area code) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Trading Symbol(s) Name of each exchange on which registered Common Stock, $.05 par value PFE New York Stock Exchange 0.000% Notes due 2020 PFE20A New York Stock Exchange 0.250% Notes due 2022 PFE22 New York Stock Exchange 1.000% Notes due 2027 PFE27 New York Stock Exchange Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ☒ No ☐ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ☐ No ☒ Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

UNITED NATIONS SYSTEM Annual Statistical Report 2005

Annual Statistical Report 2005 • Procurement of Goods & Services • All Sources of Funding • UNDP Funding • Procurement from DAC Member Countries • International & National Project Personnel • United Nations Volunteers • Fellowships Published: July 2006 by UNITED NATIONS SYSTEM Annual Statistical Report 2005 Procurement of Goods and Services • All Sources of Funding • UNDP Funding Procurement from DAC Member Countries International & National Project Personnel United Nations Volunteers Fellowships July 2006 Copyright © 2006 by the United Nations Development Programme 1 UN Plaza, New York, NY 10017, USA All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of UNDP/IAPSO. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................................... 1 GLOASSARY OF TERMS ...................................................................................................... 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: ALL SOURCES OF FUNDING (UN SYSTEM)............................ 4 PROCUREMENT OF GOODS AND SERVICES - ALL SOURCES OF FUNDING Procurement of goods by country of procurement and services by country of head office ................................................................................................... 9 Procurement by UN agency ...................................................................................... -

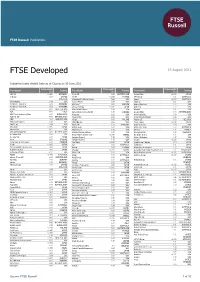

FTSE Developed

2 FTSE Russell Publications 19 August 2021 FTSE Developed Indicative Index Weight Data as at Closing on 30 June 2021 Index weight Index weight Index weight Constituent Country Constituent Country Constituent Country (%) (%) (%) 1&1 AG <0.005 GERMANY Alcon AG 0.05 SWITZERLAND Aozora Bank <0.005 JAPAN 3i Group 0.03 UNITED Ald SA <0.005 FRANCE APA Group 0.01 AUSTRALIA KINGDOM Alexandria Real Estate Equity 0.04 USA Appen <0.005 AUSTRALIA 3M Company 0.19 USA Alexion Pharm 0.07 USA Apple Inc. 3.61 USA A P Moller - Maersk A 0.02 DENMARK Alfa Laval 0.02 SWEDEN Applied Materials 0.22 USA A P Moller - Maersk B 0.03 DENMARK Alfresa Holdings <0.005 JAPAN Aptiv PLC 0.07 USA a2 Milk 0.01 NEW ZEALAND Align Technology Inc 0.08 USA Aramark 0.01 USA A2A 0.01 ITALY Alimentation Couche-Tard B 0.05 CANADA Arcelor Mittal 0.04 NETHERLANDS AAC Technologies Holdings 0.01 HONG KONG Alleghany 0.02 USA Arch Capital Gp 0.03 USA Aalberts NV 0.01 NETHERLANDS Allegion PLC 0.02 USA Archer Daniels Midland 0.06 USA ABB 0.1 SWITZERLAND Allegro 0.01 POLAND Argenx S.E 0.03 BELGIUM Abbott Laboratories 0.34 USA Alliant Energy 0.02 USA Ariake Japan <0.005 JAPAN AbbVie Inc 0.33 USA Allianz SE 0.17 GERMANY Arista Networks 0.04 USA ABC-Mart <0.005 JAPAN Allstate Corp 0.07 USA Aristocrat Leisure 0.03 AUSTRALIA Abiomed Inc 0.02 USA Ally Financial 0.03 USA Arkema 0.01 FRANCE ABN AMRO Bank NV 0.01 NETHERLANDS Alnylam Pharmaceuticals 0.03 USA Aroundtown SA 0.02 GERMANY Accenture Cl A 0.31 USA Alony Hetz Properties & Inv <0.005 ISRAEL Arrow Electronics 0.01 USA Acciona S.A. -

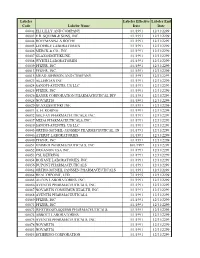

Participating Labelers.Xlsx

Labeler Labeler Effective Labeler End Code Labeler Name Date Date 00002 ELI LILLY AND COMPANY 1/1/1991 12/31/2299 00003 E.R. SQUIBB & SONS, INC. 1/1/1991 12/31/2299 00004 HOFFMANN-LA ROCHE 1/1/1991 12/31/2299 00005 LEDERLE LABORATORIES 1/1/1991 12/31/2299 00006 MERCK & CO., INC. 1/1/1991 12/31/2299 00007 GLAXOSMITHKLINE 1/1/1991 12/31/2299 00008 WYETH LABORATORIES 1/1/1991 12/31/2299 00009 PFIZER, INC 1/1/1991 12/31/2299 00013 PFIZER, INC. 1/1/1991 12/31/2299 00015 MEAD JOHNSON AND COMPANY 1/1/1991 12/31/2299 00023 ALLERGAN INC 1/1/1991 12/31/2299 00024 SANOFI-AVENTIS, US LLC 1/1/1991 12/31/2299 00025 PFIZER, INC. 1/1/1991 12/31/2299 00026 BAYER CORPORATION PHARMACEUTICAL DIV. 1/1/1991 12/31/2299 00028 NOVARTIS 1/1/1991 12/31/2299 00029 GLAXOSMITHKLINE 1/1/1991 12/31/2299 00031 A. H. ROBINS 1/1/1991 12/31/2299 00032 SOLVAY PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. 1/1/1991 12/31/2299 00037 MEDA PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. 1/1/1991 12/31/2299 00039 SANOFI-AVENTIS, US LLC 1/1/1991 12/31/2299 00045 ORTHO-MCNEIL-JANSSEN PHARMECEUTICAL, IN 1/1/1991 12/31/2299 00046 AYERST LABORATORIES 1/1/1991 12/31/2299 00049 PFIZER, INC 1/1/1991 12/31/2299 00051 UNIMED PHARMACEUTICALS, INC 10/1/1997 12/31/2299 00052 ORGANON USA INC. 1/1/1991 12/31/2299 00053 CSL BEHRING 1/1/1991 12/31/2299 00054 ROXANE LABORATORIES, INC. -

UNITED NATIONS SYSTEM Annual Statistical Report 2005

Annual Statistical Report 2005 • Procurement of Goods & Services • All Sources of Funding • UNDP Funding • Procurement from DAC Member Countries • International & National Project Personnel • United Nations Volunteers • Fellowships Published: July 2006 by UNITED NATIONS SYSTEM Annual Statistical Report 2005 Procurement of Goods and Services • All Sources of Funding • UNDP Funding Procurement from DAC Member Countries International & National Project Personnel United Nations Volunteers Fellowships July 2006 Copyright © 2006 by the United Nations Development Programme 1 UN Plaza, New York, NY 10017, USA All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of UNDP/IAPSO. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................................... 1 GLOASSARY OF TERMS ...................................................................................................... 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: ALL SOURCES OF FUNDING (UN SYSTEM)............................ 4 PROCUREMENT OF GOODS AND SERVICES - ALL SOURCES OF FUNDING Procurement of goods by country of procurement and services by country of head office ................................................................................................... 9 Procurement by UN agency ...................................................................................... -

Downloaded to a PC Or PDA

DDT Issue10 NOVEMBER05 11/28/05 4:27 PM Page 1 NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2005 Vol 5 No 10 IN THIS ISSUE Corporate Profiles 12 Drug Delivery Technologies 76 Excipients, Polymers, Liposomes & Lipids 92 Contract Pharmaceutical & Biological Development Services 98 Laboratory Testing & Analytical Equipment & Sotware 109 Technology Spotlight 113 The science & business of specialty pharma, biotechnology, and drug delivery www.drugdeliverytech.com DDT Issue10 NOVEMBER05 11/7/05 3:41 PM Page 2 NO BARRIERS. NEW FRONTIERS. COMPLEX CHALLENGES, INNOVATIVE SOLUTIONS. For 35 years, ALZA has led the drug delivery industry in developing extraordinary products based on our transdermal, oral, implantable, and liposomal delivery platforms. More than 30 products in 80 countries are based on ALZA’s novel drug delivery and targeting technologies. Today, ALZA’s dedicated researchers and scientists are addressing the complex challenges of delivering small molecules and biopharmaceuticals, with the commitment to create better medicines that improve healthcare for patients worldwide. Visit www.alza.com to learn more. © 2003 ALZA Corporation LEADING THE NEXT GENERATION OF DRUG DELIVERY DDT Issue10 NOVEMBER05 11/5/05 8:12 AM Page 3 Inhalation and transdermal technology from 3M w Novel Dry Powder Inhaler Ne Gives you the edge in a from MicroDose Technologiescompetitive environment The MicroDose dry powder inhaler, CFC-free metered dose inhaler and transdermal drug delivery systems customized to your specifications ៑ A wide variety of components to meet your needs ៑ Nearly 50 years’ experience in inhalation drug delivery technology and skin adhesion products ៑ Fully integrated development and manufacturing processes ៑ Global regulatory expertise ៑ Project management support available from concept through commercialization Developing proven solutions that enable your success. -

2019 MED-Project Annual Report

2019 MED-Project Annual Report Alameda County, California March 1, 2020 Prepared By: MED-Project LLC Submitted To: Alameda County, Department of Environmental Health Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................. 4 Participating Producers ....................................................................................................... 5 Collection Method and Weight ............................................................................................ 5 A. Kiosks .................................................................................................................................... 5 B. Mail-Back Packages ................................................................................................................. 5 C. Take-Back Events ................................................................................................................... 5 D. Total Weight of Collected Unwanted Medicine ........................................................................... 5 Kiosk Drop-Off Locations, Mail-Back Distribution, and Take-Back Events ......................... 5 Kiosk Drop-Off Locations ......................................................................................................... 6 Mail-Back Package Distribution Locations .................................................................................. 6 Number of Mail-Back Packages Provided to Home-Bound and Under Served Residents ............... -

Drug Companies Participating in MED-Project Stewardship Plan (February 9, 2017)

Drug Companies Participating in MED-Project Stewardship Plan (February 9, 2017) Participating Drug Company Parent Drug Company 3M Corporation 3M Corporation 3M Critical and Chronic Care 3M Corporation 3M Drug Delivery Systems 3M Corporation 3M Infection Prevention 3M Corporation 3M Oral Care 3M Corporation AbbVie Inc. AbbVie Inc. ACADIA Pharmaceuticals Inc. ACADIA Pharmaceuticals Inc. Accord Healthcare Inc. Accord Healthcare Inc. Acorda Therapeutics, Inc. Acorda Therapeutics, Inc. Acorda Therapeutics, Inc. Acorda Therapeutics, Inc. Actavis Generics Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc. Actavis Pharma, Inc. (only for labeler code 52544) Allergan, Inc. Actelion Pharmaceuticals US, Inc. Actelion Pharmaceuticals US, Inc. Advanced Vision Research Inc. d.b.a. Akorn Consumer Health Akorn, Inc. Aegerion Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Aegerion Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Afaxys Inc. Afaxys Inc. Afaxys Pharmaceuticals (a division of Afaxys Inc.) Afaxys Inc. Affordable Pharmaceuticals LLC Braintree Laboratories Inc. Akorn Animal Health, Inc. Akorn, Inc. Akorn, Inc. Akorn, Inc. Akrimax Pharmaceuticals, LLC Akrimax Pharmaceuticals, LLC AKRON COATING & ADHESIVES AKRON COATING & ADHESIVES Alcon Laboratories, Inc. Novartis Group Companies Allergan Sales LLC Allergan, Inc. Allergan USA, Inc. Allergan, Inc. Allergan, Inc. Allergan, Inc. Alva-Amco Pharmacal Companies, Inc. Alva-Amco Pharmacal Companies, Inc. AMAG Pharma USA, Inc. AMAG Pharmaceuticals, Inc. AMAG Pharmaceuticals, Inc. AMAG Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Amarin Corp Amarin Pharma, Inc. Amarin Corp. PLC Amarin Pharma, Inc. Amarin Pharma, Inc. Amarin Pharma, Inc. Amarin Pharmaceuticals Ireland Ltd. Amarin Pharma, Inc. American Regent, Inc. Daiichi Sankyo, Inc. Amerisource Health Services Corporation DBA: American Health Amerisource Health Services Corporation DBA: American Health Packaging Packaging Amgen Inc. Amgen Inc. Amgen USA Amgen Inc. Amneal Pharmaceuticals LLC Amneal Pharmaceuticals LLC Anchen Pharmaceuticals, Inc. -

Washington State 2020 Annual Report (PDF)

First MED-Project Annual Report For 2019 Operating Period State of Washington Due July 1, 2020 Prepared By: MED-Project WA, LLC Submitted To: Washington State Department of Health Table of Contents I. Executive Summary ............................................................................................................... 3 II. Annual Budget ...................................................................................................................... 3 Table 1: Annual Budget .................................................................................................................. 4 Appendix A ................................................................................................................................ 5 List of Covered Manufacturers ......................................................................................................... 5 Table 2: List of Covered Manufacturers.......................................................................................... 21 2 I. Executive Summary MED-Project WA, LLC’s (“MED-Project”) Product Stewardship Plan for Covered Drugs from Households (“Plan”) was approved by the Washington State Department of Health (the "Department") on May 25, 2020. Per the Plan, MED-Project will initiate operations by November 21, 2020, which is within 180 days of the Plan approval date. This first Annual Report for the 2019 reporting period was requested by the Department and includes an update to the annual budget that occurred after the submission of the proposed Plan and