Catholicism and the Jews in Post-Communist Poland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dignity М Freedom М Human Rights

Differences in the understanding of human dignity are born from the rejection by EU legislation of the religious element and DIGNITY – FREEDOM the laws of nature, which for Christians are essential sources of human dignity, freedom and human rights. The EU developed – HUMAN RIGHTS them mostly from the state endowment, and relative stability is not attributed to them. In reading the convergences and divergences in the understanding of these three fundamental The Role of the Catholic Church concepts of human dignity, freedom and human rights, a particular difficulty in dialogue with the EU comes from the in the European Integration Process language which we use to express our views. The terms dignity, freedom and human rights mean something completely different This publication contains the transcripts in both the Christian and Union contexts. This discrepancy arose from speeches and discussions during the conference because Christianity derives dignity, freedom and human rights in Krakow on 25-26 September 2015 from the truth, and this is the revealed truth, while the EU has adopted the principle of freedom as its source. [...] Bp Prof. Tadeusz Pieronek 0*%)$#$%0$ 8#*0$99: <$;9(&$ <<<=>*90(*4?$"#*6,=*#-=64 )"%.9 8,#&L 8,#4(,+$%& DIGNITY – FREEDOM HUMAN RIGHTS NBO ! M M 8 5 3 N 2 7 M B @ The Pontifical University The Robert Schuman The Konrad Adenauer The Group ‘Wokó³ nas’ European People’s Party Commission of John Paul II Foundation Foundation of the European People's Party Publishing House of -

Controversies Over Holocaust Memory and Holocaust Revisionism in Poland and Moldova

Kantor Center Position Papers Editor: Mikael Shainkman March 2014 HOLOCAUST MEMORY AND HOLOCAUST DENIAL IN POLAND AND MOLDOVA: A COMPARISON Natalia Sineaeva-Pankowska* Executive Summary After 1989, post-communist countries such as Poland and Moldova have been faced with the challenge of reinventing their national identity and rewriting their master narratives, shifting from a communist one to an ethnic-patriotic one. In this context, the fate of local Jews and the actions of Poles and Moldovans during the Holocaust have repeatedly proven difficult or even impossible to incorporate into the new national narrative. As a result, Holocaust denial in various forms initially gained ground in post-communist countries, since denying the Holocaust, or blaming it on someone else, even on the Jews themselves, was the easiest way to strengthen national identities. In later years, however, Polish and Moldovan paths towards re-definition of self have taken different paths. At least in part, this can be explained as a product of Poland's incorporation in the European unification project, while Moldova remains in limbo, both in terms of identity and politics – between the Soviet Union and Europe, between the past and the future. Introduction This paper focuses on the debate over Holocaust memory and its link to national identity in two post-communist countries, Poland and Moldova, after 1989. Although their historical, political and social contexts and other factors differ, both countries possess a similar, albeit not identical, communist legacy, and both countries had to accept ‘inconvenient’ truths, such as participation of members of one’s own nation in the Holocaust, while building-rebuilding their new post-communist national identities during a period of social and political transformation. -

PROVISIONAL LIST of PARTICIPANTS As of 21 October 2017

PROVISIONAL LIST OF PARTICIPANTS as of 21 October 2017 AUSTRIA Bischof Dr. Michael BÜNKER AB Lutheran Bishop of Austria H.E. Mr. Alfons M. KLOSS Ambassador of Austria to the Holy See Mr Lukas MANDL State Parliament Member Sr. Beatrix MAYRHOFER Präsidentin der Vereinigung der Frauenorden Österreichs Dr. Gabriele MOSER State Parliament Member Ms. Evelyn REGNER Member of the European Parliament DDr. Severin RENOLDNER Theologian, former State Parliament Member DDr. Peter SCHIPKA General Secretary of the Austrian Bishops' Conference S.E.R. Mons. D. Aloïs SCHWARZ Bishop of Gurk-Klagenfurt Dr. Irmfried SCHWIMANN European Commission S.E.R. Mons. Ägidius ZSIFKOVICS Bishop of Eisenstadt, Delegate to COMECE BELGIUM S.E. Le Comte J. CORNET d'ELZIUS Ambassadeur de Belgique près le Saint Siège Mr Gilles de KERCHOVE Counter-Terrorism Coordinator for the European Union Prof. Vincent DUJARDIN President of the Institut d’études européennes at the Catholic University of Louvain (UCL) Most Rev. Fr. Franck JANIN President of the Conference of European Provincials S.E.R. Mons. Jean KOCKEROLS Auxiliary Bishop of the Diocese of Mechelen-Brussels, COMECE First Vice-President Mr Philippe LAMBERTS Co-Chairman of the Greens–European Free Alliance in the European Parliament Dr. Pieter-Jan MEERSMANN Ambassade de Belgique près le Saint Siège Mgr. Dirk SMET Conseiller, Ambassade de Belgique près le Saint Siège Mr Enrico TRAVERSA European Commission Mr Steven VANACKERE former Deputy Prime Minister, former Minister of Foreign Affairs Ms Katrien VERHEGGE Director general of Kind en Gezin BULGARIA H.E. Prof. Vladimir GRADEV Former Ambassador of Bulgaria to the Holy See, Professor of Philosophy at the University of Sofia. -

From Understanding to Cooperation Promoting Interfaith Encounters to Meet Global Challenges

20TH ANNUAL EPP GROUP INTERCULTURAL DIALOGUE WITH CHURCHES AND RELIGIOUS INSTITUTIONS FROM UNDERSTANDING TO COOPERATION PROMOTING INTERFAITH ENCOUNTERS TO MEET GLOBAL CHALLENGES Zagreb, 7 - 8 December 2017 20TH ANNUAL EPP GROUP INTERCULTURAL DIALOGUE WITH CHURCHES AND RELIGIOUS INSTITUTIONS / 3 PROGRAMME 10:00-12:30 hrs / Sessions I and II The role of religion in European integration process: expectations, potentials, limits Wednesday, 6 December 10:00-11:15 hrs Session I 20.30 hrs. / Welcome Reception hosted by the Croatian Delegation / Memories and lessons learned during 20 years of Dialogue Thursday, 7 December Co-Chairs: György Hölvényi MEP and Jan Olbrycht MEP, Co-Chairmen of 09:00 hrs / Opening the Working Group on Intercultural Activities and Religious Dialogue György Hölvényi MEP and Jan Olbrycht MEP, Co-Chairmen of the Working Opening message: Group on Intercultural Activities and Religious Dialogue Dubravka Šuica MEP, Head of Croatian Delegation of the EPP Group Alojz Peterle MEP, former Responsible of the Interreligious Dialogue Welcome messages Interventions - Mairead McGuinness, First Vice-President of the European Parliament, - Gordan Jandroković, Speaker of the Croatian Parliament responsible for dialogue with religions (video message) - Joseph Daul, President of the European People’ s Party - Joseph Daul, President of the European People’ s Party - Vito Bonsignore, former Vice-Chairman of the EPP Group responsible for - Andrej Plenković, Prime Minister of Croatia Dialogue with Islam - Mons. Prof. Tadeusz Pieronek, Chairman of the International Krakow Church Conference Organizing Committee - Stephen Biller, former EPP Group Adviser responsible for Interreligious Dialogue Discussion 20TH ANNUAL EPP GROUP INTERCULTURAL DIALOGUE WITH CHURCHES AND RELIGIOUS INSTITUTIONS / 5 4 /20TH ANNUAL EPP GROUP INTERCULTURAL DIALOGUE WITH CHURCHES AND RELIGIOUS INSTITUTIONS 11:15-12:30 hrs. -

The Ethical Dimension of Politics

[…] The eleventh Krakow conference, held in September 2011 The Ethical Dimension of Politics in Tomaszowice, near Krakow, concerned a topic that is difficult and has been annually postponed – that of the ethical dimension of politics. Its aim was to draw a conclusion based on thoughts from the previous conference, during which the contribution The Role of the Catholic Church of Christians in the process of European integration was discussed. This time it was a matter of defining what role Christian politicians in the European Integration Process have to fulfil in this process, especially those who as part of its structure and decision-making bodies bear responsibility for its shape, which includes its ethical shape. This is not a simple task because it is in a way an account This publication contains the transcripts of conscience for these politicians, who often face ethical dilem- from speeches and discussions during the conference mas, and who establish the guidelines for many aspects of the lives in Krakow on 9-10 September 2011 of European citizens, who profess different faiths and worldviews; people who invoke their conscience, which is shaped by principles that are often at odds with those recognised by others. […] Bp. Prof. Tadeusz Pieronek The Ethical Dimension of Politics Gliwice 2012 nas’ Publishing House ’Wokó³ The Ethical Dimension of Politics The Role of the Catholic Church in the European Integration Process This publication contains the transcripts from speeches and discussions -

Constructions and Instrumentalization of the Past: a Comparative Study on Memory Management in the Region

CBEES State of the Region Report 2020 Constructions and Instrumentalization of the Past A Comparative Study on Memory Management in the Region Published with support from the Foundation for Baltic and East European Studies (Östersjstiftelsen) Constructions and Instrumentalization of the Past A Comparative Study on Memory Management in the Region December 2020 Publisher Centre for Baltic and East European Studies, CBEES, Sdertrn University © CBEES, Sdertrn University and the authors Editor Ninna Mrner Editorial Board Joakim Ekman, Florence Frhlig, David Gaunt, Tora Lane, Per Anders Rudling, Irina Sandomirskaja Layout Lena Fredriksson, Serpentin Media Proofreading Bridget Schaefer, Semantix Print Elanders Sverige AB ISBN 978-91-85139-12-5 4 Contents 7 Preface. A New Annual CBEES Publication, Ulla Manns and Joakim Ekman 9 Introduction. Constructions and Instrumentalization of the Past, David Gaunt and Tora Lane 15 Background. Eastern and Central Europe as a Region of Memory. Some Common Traits, Barbara Trnquist-Plewa ESSAYS 23 Victimhood and Building Identities on Past Suffering, Florence Frhlig 29 Image, Afterimage, Counter-Image: Communist Visuality without Communism, Irina Sandomirskaja 37 The Toxic Memory Politics in the Post-Soviet Caucasus, Thomas de Waal 45 The Flag Revolution. Understanding the Political Symbols of Belarus, Andrej Kotljarchuk 55 Institutes of Trauma Re-production in a Borderland: Poland, Ukraine, and Lithuania, Per Anders Rudling COUNTRY BY COUNTRY 69 Germany. The Multi-Level Governance of Memory as a Policy Field, Jenny Wstenberg 80 Lithuania. Fractured and Contested Memory Regimes, Violeta Davoliūtė 87 Belarus. The Politics of Memory in Belarus: Narratives and Institutions, Aliaksei Lastouski 94 Ukraine. Memory Nodes Loaded with Potential to Mobilize People, Yuliya Yurchuk 106 Czech Republic. -

The 617St Academic Year at the Pontifical University of John Paul II in Krakow

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Analecta Cracoviensia „Analecta Cracoviensia” 46 (2014), s. 315–360 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15633/acr.971 The Canonization of the University Patron: The 617st Academic Year at the Pontifical University of John Paul II in Krakow Without a doubt, one of the most important events of the past academic year was the canonization of our founder, Pope Blessed John Paul II. It is especially worth noting that the decision about the canonization and its date was announced public- ly precisely on the day of our university’s pilgrimage to Kalwaria Zebrzydowska. It was during a consistory on September 30th 2013 that Pope Francis announced that he would canonize two popes, John XXIII and John Paul II, on April 27th 2014, Divine Mercy Sunday. It immediately became apparent that this would be a unique event that would forever remain etched in our memories. Along with the inauguration of the new academic year, preparations for the fullest experience of the canonization of John Paul II – the founder, caring guardian and ultimately illustrious patron of the university – were undertaken. These were not only preparations related to the organization of travel to the canonization ceremony, but above all those whose purpose was to deepen the knowledge of the great Polish pope and the popular- ization of his teachings. Symposia and academic conferences organized on this occasion will be presented below in separate summaries. It was with great joy that we heard the words of the formula for canonization -

Introduction

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. INTRODUCTION “We were taught as children”—I was told by a seventy- year-old Pole—“that we Poles never harmed anyone. A partial abandonment of this morally comfortable position is very, very difficult for me.” —Helga Hirsch, a German journalist, in Polityka, 24 February 2001 HE COMPLEX and often acrimonious debate about the charac- ter and significance of the massacre of the Jewish population of T the small Polish town of Jedwabne in the summer of 1941—a debate provoked by the publication of Jan Gross’s Sa˛siedzi: Historia za- głady z˙ydowskiego miasteczka (Sejny, 2000) and its English translation Neighbors: The Destruction of the Jewish Community in Jedwabne, Poland (Princeton, 2001)—is part of a much wider argument about the totali- tarian experience of Europe in the twentieth century. This controversy reflects the growing preoccupation with the issue of collective memory, which Henri Rousso has characterized as a central “value” reflecting the spirit of our time.1 One key element in the understanding of collec- tive memory is the “dark past” of nations—those aspects of the na- tional past that provoke shame, guilt, and regret; this past needs to be integrated into the national collective identity, which itself is continu- ally being reformulated.2 In this sense, memory has to be understood as a public discourse that helps to build group identity and is inevita- bly entangled in a relationship of mutual dependence with other iden- tity-building processes. -

How Does Religion Matter Today in Poland? Secularization in Europe and the 'Causa Polonia Semper Fidelis' Arnold, Maik

www.ssoar.info How Does Religion Matter Today in Poland? Secularization in Europe and the 'Causa Polonia Semper Fidelis' Arnold, Maik Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Sammelwerksbeitrag / collection article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Arnold, M. (2012). How Does Religion Matter Today in Poland? Secularization in Europe and the 'Causa Polonia Semper Fidelis'. In M. Arnold, & P. Łukasik (Eds.), Europe and America in the Mirror: Culture, Economy, and History (pp. 199-238). Krakau: Nomos. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-337806 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under Deposit Licence (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, non- Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, transferable, individual and limited right to using this document. persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses This document is solely intended for your personal, non- Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für commercial use. All of the copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public. dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke By using this particular document, you accept the above-stated vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder conditions of use. -

Comece Annual Report 2009

| 2 CONTENTS COMECE ANNUAL REPORT 2009 1 Foreword 3 2 A new Secretary general for COMECE 4 3 Reports of the Executive Committee 4 4 COMECE Plenary Assemblies 5 4.1 Spring 2009 5 4.2 Autumn 2009 6 5 Working Groups 7 5.1 Bioethics reflection group 7 5.2 Working group on migration 7 5.3 Social Affairs 8 5.4 Legal Affairs 8 5.5 Ad hoc group on a Memorandum on religious freedom 10 5.6 Ad Hoc Group on a Memorandum on non-discrimination 10 5.7 Ad Hoc Group ‘Coordination of Churches combating Poverty’ 10 6 Initiatives 11 6.1 European Elections 2009: COMECE Bishops Declaration 11 6.2 Meeting Young Citizens debate, 8-10 May 12 6.3 International Summer School Seggauberg 13 6.4 Second series of seminars “Islam, Christianity and Europe” 13 6.5 First Catholic Social days in Gdansk 8-11 October 14 7 Dialogue with the EU 16 7.1 Summit meeting of religious leaders, 11 May 16 7.2 Presidency meeting 17 7.3 Dialogue Seminars 18 8 List of activities 2008 19 8.1 Consultations 19 8.2 Other Contributions 19 8.3 Conferences (co-) organised by COMECE 19 8.4 Visitor groups 20 9 Publications 20 10 Information and publication Policy 21 11 Finances 21 12 Members 22 13 Secretariat 22 COMECE ANNUAL REPORT - 2009 FOREWORD | 3 1| FOREWORD Dear Readers, communities: The European Union respects the status which Churches and religious communities have in the respective The year 2009 marked a number of Member States and will not infringe this. -

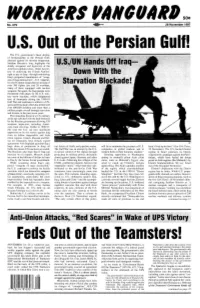

Anti-Uni.On Attacks, "Redscar~~~'\;;Jn{.~~E.;Q1:Lj~S

50C!: No. 679 ~X423 28 November 1997 u.s. Out 01 the Persian Gull! The U.S. government's latest display of l;lrinkmanship in the Persian Gulf, directed against its favorite bogeyman, Saddam Hussein's Iraq, highlights the deadly arrogance and hypocrisy of the American capitalist class. Under the pre text of enforcing the United Nations' right to spy on Iraq-through monitoring Iraq's purported manufacture of "weap ons of mass destruction"-U.S. imperial ist chief Clinton dispatched an armada of over 300 fighter jets and 20 warships, many of these equipped with nuclear weapons. Yet again, the Iraqi people were threatened with attack by the U.S. mili tary terror machine, which slaughtered tens of thousands during the 1990-91 Gulf War and continues to enforce a UN sponsored blockade which has killed well over 600,000 children and more than a million people overall through starvation and disease in the past seven years. The immediate threat of a U.S. military strike has subsided with the deal brokered by the Russian government allowing UN weapons inspectors, including Ameri cans, back into Iraq. Unlike in 1990-91, this time the U.S. ran into significant opposition to its war moves against Iraq from its fellow imperialists and Arab client regimes. French, Russian and Ital ian oil companies have already signed agreements with Baghdad guaranteeing a AP huge share of production in Iraqi oil tral Asian oil fields and pipeline routes. will be to minimize the presence of U.S. hasn't lived up to them" (New York Times, fields the minute UN sanctions are ended. -

1997 Human Rights Report: Poland Page 1 of 18

1997 Human Rights Report: Poland Page 1 of 18 The State Department web site below is a permanent electro information released prior to January 20, 2001. Please see w material released since President George W. Bush took offic This site is not updated so external links may no longer func us with any questions about finding information. NOTE: External links to other Internet sites should not be co endorsement of the views contained therein. U.S. Department of State Poland Country Report on Human Rights Practices for 1997 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, January 30, 1998. POLAND Poland is a parliamentary democracy based on a multiparty political system and free and fair elections. The President shares power with the Prime Minister, the Council of Ministers, and the bicameral Parliament (Senate and Sejm). Poland has held two presidential and three parliamentary elections in the 8 years since the end of communism. For much of the year, the governing coalition, composed of the Democratic Left Alliance (SLD), a successor to the former Communist Party, and the Polish Peasant Party (PSL), a successor to the Peasant Party of the Communist era, had a nearly two-thirds majority in both houses of Parliament. In parliamentary elections held on September 21, Solidarity Electoral Action (AWS)--a broad coalition of rightist, center-right, and Christian-national parties anchored by the Solidarity trade union--gained 33.9 percent of the vote. The new Government is a two-party coalition composed of AWS and its junior partner, the centrist Freedom Union (UW). The judiciary is independent.