Sondheim's Sweeney Todd: a Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Don Giovanni Sweeney Todd

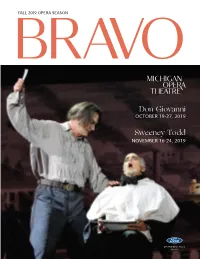

FALL 2019 OPERA SEASON B R AVO Don Giovanni OCTOBER 19-27, 2019 Sweeney Todd NOVEMBER 16-24, 2019 2019 Fall Opera Season Sponsor e Katherine McGregor Dessert Parlor …at e Whitney. Named a er David Whitney’s daughter, Katherine Whitney McGregor, our intimate dessert parlor on the Mansion’s third oor features a variety of decadent cakes, tortes, and miniature desserts. e menu also includes chef-prepared specialties, pies, and “Drinkable Desserts.” Don’t miss the amazing aming dessert station featuring Bananas Foster and Cherries Jubilee. Reserve tonight’s table online at www.thewhitney.com or call 313-832-5700 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit Pre- eater Menu Available on performance date with today’s ticket. Choose one from each course: FIRST COURSE Caesar Side Salad Chef’s Soup of the Day e Whitney Duet MAIN COURSE Grilled Lamb Chops Lake Superior White sh Pan Roasted “Brick” Chicken Sautéed Gnocchi View current menus DESSERT and reserve online at Chocolate Mousse or www.thewhitney.com Mixed Berry Sorbet with Fresh Berries or call 313-832-5700 $39.95 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit e Katherine McGregor Dessert Parlor …at e Whitney. Named a er David Whitney’s daughter, Katherine Whitney McGregor, our intimate dessert parlor on the Mansion’s third oor features a variety of decadent cakes, tortes, and miniature desserts. e menu also includes chef-prepared specialties, pies, and “Drinkable Desserts.” Don’t miss the amazing aming dessert station featuring Bananas Foster and Cherries Jubilee. Reserve tonight’s table online at www.thewhitney.com or call 313-832-5700 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit Pre- eater Menu Available on performance date with today’s ticket. -

Read an Excerpt

Excerpt Terms & Conditions This excerpt is available to assist you in the play selection process. You may view, print and download any of our excerpts for perusal purposes. Excerpts are not intended for performance, classroom or other academic use. In any of these cases you will need to purchase playbooks via our website or by phone, fax or mail. A short excerpt is not always indicative of the entire work, and we strongly suggest reading the whole play before planning a production or ordering a cast quantity of scripts. Family Plays SWEENEY TODD (Demon Barber of the Barbary Coast) Thriller adapted by TIM KELLY © Family Plays SWEENEY TODD Thriller. Adapted by Tim Kelly. Cast: 8m., 12w., extras. This non-musical version of Sweeney Todd, the world’s most heartless villain, is based on the same “penny dreadful” stories as the Sondheim musical (this script predates the musical). Sweeney Todd lures rich victims into his barber shop, puts them in a “special chair,” and ... where do they go? Ask Mrs. Lovett, owner of a nearby pastry shop which specializes in meat pies. Tim Kelly’s version is a delicious spoof of the Gay Nineties (1890s) melodrama, full of fun and suspense. Replete with the excitement, suspense and laughter that everybody hopes for in a melodrama—this play is of much higher quality than the burlesque, trite “mellerdrammers” that are found on second-rate stages. Directors will be proud to present this play—whether it’s for an annual fun-melodrama or a major production.Sweeney Todd is fast-moving and side-splitting .. -

Download Transcript (PDF)

Larry Sidor Oral History Interview, November 6, 2015 Title “From Olympia to Deschutes to Crux: A Brewer's Life” Date November 6, 2015 Location Valley Library, Oregon State University. Summary In the interview, Sidor discusses his family background and rural upbringing in La Grande, Oregon, commenting on his father's activities as an OSU Extension Agent, his own boyhood interests in mechanical work, and the life histories of his mother and his siblings. From there, Sidor recounts his undergraduate years at Oregon State University, noting his switch in majors from Mechanical Engineering to Food Science, and commenting on the curriculum then available to undergraduates in the Food Science department. Sidor likewise reflects on the research that he conducted while a student and, in particular, his interest in winemaking during that time. From there, Sidor details the circumstances by which he declined a handful of job opportunities in the wine industry, opted instead to travel for a year in Europe, and began considering a career in brewing as a result of his experiences in Germany. He then traces his first connection with the Olympia Brewing Company; outlines his advancement within the company from packing quality control technician, to assistant brewmaster, to operations manager; shares his perspective on the brewing culture then prevalent at Olympia; and speaks of the connections that he made with hop growers in Washington and Oregon. Sidor next provides an overview of his years working at the S.S. Steiner company, shares his memories of the rise of microbreweries in the 1980s and 1990s, and reflects on the relationships that Steiner maintained with agricultural scientists at OSU. -

Sweeney Todd the Demon Barber of Fleet Street May 10 – June 7, 2020 Edu TABLE of CONTENTS

A NOISE WITHIN’S 2019-2020 REPERTORY THEATRE SEASON AUDIENCE GUIDE Stephen Sondheim’s Sweeney Todd The Demon Barber Of Fleet Street May 10 – June 7, 2020 Edu TABLE OF CONTENTS Character Map . 3 Synopsis . 4 About the Author: George Dibdin Pitt . 5 About the Adaptors: Christopher Bond, Hugh Wheeler, and Stephen Sondheim . 7 History of Sweeney Todd: A Timeline . 9 Change in the Air: The Transition from the Industrial Revolution to the Victorian Era . 10 Pretty Women: The Role of Women in 19th Century England . 11 The Great Divide: Social Inequality in Industrial and Victorian England . 14 Melodrama and Musicals . 15 The Evolution of the Sweeney Todd Story from Melodrama to Musical . 17 Themes . 18 Revenge . 18 Love and Desire . 18 Freedom and Captivity . 19 Madness . 19 Ken Booth Lighting Designer . 20 Additional Resources . 21 A NOISE WITHIN’S EDUCATION PROGRAMS MADE POSSIBLE IN PART BY: Ann Peppers Foundation The Green Foundation Capital Group Companies Kenneth T . and Michael J . Connell Foundation Eileen L . Norris Foundation The Dick and Sally Roberts Ralph M . Parsons Foundation Coyote Foundation Steinmetz Foundation The Jewish Community Dwight Stuart Youth Fund Foundation 3 A NOISE WITHIN 2019/20 REPERTORY SEASON | Spring 2020 Study Guide Sweeney Todd CHARACTER MAP Mrs. Lovett The owner of a struggling meat pie shop . She knew Sweeney Todd before he was sent to Australia, and she helps him set up a barbershop when he returns to London . Sweeney Todd/Benjamin Barker An English barber formerly known Beggar Woman/Lucy Barker as Benjamin Barker . After spending A woman who has gone mad over 15 years wrongfully incarcerated in time . -

AUGUSTANA COLLEGE THEATRE 2015-2016 Season Crime and Justice

AUGUSTANA COLLEGE THEATRE 2015-2016 Season Crime and Justice WVIK WVIKWVIK WVIis a proud WVIK partner in theWV Quad Cities’ WVIKarts and cultureWV WVIKcommunity WVIKWVIK WVIKWVIKWVIKwvik.org Augustana College Department of Theatre Arts, in conjunction with Opera@Augustana, proudly presents SWEENEY TODD The Demon Barber of Fleet Street A Musical Thriller Music and lyrics by Book by STEPHEN SONDHEIM HUGH WHEELER From an adaptation by CHRISTOPHER BOND Originally directed on Broadway by HAROLD PRINCE Orchestrations by JONATHAN TUNICK Originally produced on Broadway by RICHARD BARR, CHARLES WOODWARD, ROBERT FRYER, MARY LEA JOHNSON, MARTIN RICHARDS in association with DEAN and JUDY MANOS Directed by Music direction by JAY CRANFORD MICHELLE CROUCH SWEENEY TODD is presented through special arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI). All authorized performance materials also are supplied by MTI. www.MTIShows.com The videotaping or other video or audio recording of this production is strictly prohibited. A NOTE FROM THE DIRECTOR What a large undertaking in a short amount of time with Sondheim’s most difficult score! Kudos to the cast, crew, musical, technical and design team. Sondheim’s masterpiece about a wronged barber seeking revenge has long been a favorite of mine. Having seen the recent John Doyle Broadway revival on their final dress rehearsal, I caught Sondheim there looking perturbed. It had been deconstructed with the small cast playing their own instruments as they sang; clear storytelling had been lost. In our version, I wanted to focus completely on the relationships and reasons that drive Sweeney to action. A corrupt judge of powerful stature does the unimaginable, giving permission to a society in downward spiral to lose all sense of morality. -

A Cognitive Approach to Gestural Life in Stephen Sondheim's Musical Genres

“MY ARM IS COMPLETE”: A COGNITIVE APPROACH TO GESTURAL LIFE IN STEPHEN SONDHEIM’S MUSICAL GENRES by Diana Louise Calderazzo AB, Smith College, 1999 MA, University of Central Florida, 2005 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2012 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF THEATRE ARTS This dissertation was presented by Diana Louise Calderazzo It was defended on July 11, 2012 and approved by Marlene Behrmann, Professor, Department of Psychology, Carnegie Melon University Atillio Favorini, Professor, Department of Theatre Arts, University of Pittsburgh Kathleen George, Professor, Department of Theatre Arts, University of Pittsburgh Dissertation Director: Bruce McConachie, Professor, Department of Theatre Arts, University of Pittsburgh ii Copyright by Diana Louise Calderazzo 2012 iii “MY ARM IS COMPLETE”: A COGNITIVE APPROACH TO GESTURAL LIFE IN STEPHEN SONDHEIM’S MUSICAL GENRES Diana Louise Calderazzo, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Traditionally, musical theatre has been accepted more as a practical field than an academic one, as demonstrated by the relative scarcity of lengthy theory‐based publications addressing musicals as study topics. However, with increasing scholarly application of cognitive theories to such fields as theatre and music theory, musical theatre now has the potential to become the topic of scholarly analysis based on empirical data and scientific discussion. This dissertation seeks to contribute such an analysis, focusing on the implied gestural lives of the characters in three musicals by Stephen Sondheim, as these lives exemplify the composer’s tendency to challenge traditional audience expectations in terms of genre through his music and lyrics. -

The Dark Side of the Tune: a Study of Villains

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2008 The Dark Side Of The Tune: A Study Of Villains Michael Biggs University of Central Florida Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Biggs, Michael, "The Dark Side Of The Tune: A Study Of Villains" (2008). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 3811. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/3811 THE DARK SIDE OF THE TUNE: A STUDY OF VILLAINS by MICHAEL FREDERICK BIGGS II B.A. California State University, Chico, 2004 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in the Department of Theatre in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2008 © 2008 Michael Biggs ii ABSTRACT On “championing” the villain, there is a naïve quality that must be maintained even though the actor has rehearsed his tragic ending several times. There is a subtle difference between “to charm” and “to seduce.” The need for fame, glory, power, money, or other objects of affection drives antagonists so blindly that they’ve no hope of regaining a consciousness about their actions. If and when they do become aware, they infrequently feel remorse. -

Fall Season Oct

2018-19 Concert Series SEP. 15 Philharmonia Boston Orchestra String Players NOV. 10 From Ella FALL SEASON Saturday, Sept. 15, 7:30 p.m. Jazz Band Lorimer Chapel Eric Thomas, director (Funded by the Robert J. Strider Concert Fund) Saturday, Nov. 10, 7:30 p.m. Founded in 2008, Philharmonia Boston Orchestra is Given Auditorium, Bixler Art and Music Center composed of professional musicians from the Greater We tour Ella Fitzgerald’s musical life, from her audition at Boston area. Their vision is to serve and inspire the the Apollo Theater to her work at the helm of the Chick Webb SEP. 15 OCT. 6 OCT. 27 community by engaging in educational outreach programs, Band, and give a special nod to her Live in Berlin album. “A providing vibrant musical experiences, and introducing young Tisket A Tasket,” “Black Coffee,” “Angel Eyes,” “I Can’t Give talented musicians. Led by Jinwook Park, Colby Symphony You Anything But Love,” “Mack the Knife,” and other classic Orchestra’s dynamic director, the PBO string players will tunes will be featured. We’ll also touch on hits from Nelson present works by Bartók, Respighi, and Tchaikovsky. Riddle, Ray Brown, Joe Pass, the Duke, and the Count, and some of the other artists she influenced. OCT. 6 Traditional Flamenco with Bourassa Dance and Friends Sandeep Das and the HUM Ensemble: NOV. 11 (Funded by the Clark/Comparetti Concert Fund) Delhi to Damascus NOV. 3 NOV. 17 Saturday, Oct. 6, 7:30 p.m. Sunday, Nov. 11, 3 p.m. Page Commons Room, Cotter Union Page Commons Room, Cotter Union Flamenco artists Lindsey Bourassa (dance), Barbara (Funded by the Robert J. -

1-24-17 Opera Workshop

Williams Opera Workshop SWEENEY TODD The Demon Barber of Fleet Street A Musical Thriller Music and Lyrics by Book by STEPHEN SONDHEIM ’50 HUGH WHEELER From an Adaptation by CHRISTOPHER BOND Originally Directed On Broadway by HAROLD PRINCE Orchestrations by Jonathan Tunick Originally Produced on Broadway by Richard Barr, Charles Woodward, Robert Fryer, Mary Lea Johnson, Martin Richards in Association with Dean and Judy Manos Prelude Prologue: The Ballad of Sweeney Todd . Todd, Company Act I Scenes: 1. A street by the London docks: No Place Like London . Anthony, Todd, Beggar Woman 2. Mrs. Lovett’s Pie Shop: Worst Pies in London . Mrs. Lovett My Friends . Todd, Mrs. Lovett Ballad of Sweeney Todd, Reprise . Company 3. Judge Turpin’s House: Green Finch and Linnet Bird . Johanna Johanna (Part 1 & 2) . Anthony 4. St. Dunstan’s marketplace: Pirelli’s Entrance . Pirelli The Contest (Part 1) . Pirelli 5. Sweeney Todd’s Tonsorial Parlor: Pirelli’s Death . Pirelli 6. Outside Judge Turpin’s house: Kiss Me (Part 1) . Johanna, Anthony Ladies in their Sensitivities . Beadle 7. Sweeney Todd’s Tonsorial Parlor: Pretty Women (Part 1) . Judge, Todd Pretty Women (Part 2) . Todd, Judge, Anthony Epiphany . Todd, Mrs. Lovett 8. Mrs. Lovett’s Pie Shop: A Little Priest . Mrs. Lovett, Todd Continued on reverse side Tuesday, January 24, 2017 7:00 p.m. Chapin Hall Williamstown, Massachusetts The videotaping or other video or audio recording of this production is strictly prohibited. Act 2 9. The streets of London: Johanna—Act 2 Sequence . Anthony, Todd, Johanna, Beggar Woman 10. Mrs. Lovett’s Pie Shop: Not While I’m Around . -

Sweeney Todd the Demon Barber of Fleet Street a Musical Thriller

Reboot Theatre Company Presents Sweeney Todd The Demon Barber of Fleet Street A Musical Thriller Music and Lyrics by Stephen Sondheim Book by Hugh Wheeler From an adaptation by Christopher Bond. Originally directed on Broadway by Harold Prince. Orchestrations by Jonathan Tunic. Originally produced on Broadway by Richard Barr, Charles Woodward, Robert Fryer, Mary Lea Johnson, Martin Richards in association with Dean and Judy Manos Directed Music Direction by by Julia Griffin Aimee Hong With (In alphabetical order) Brittany Allyson, Justine Davis, Kylee Gano, Alyssa Keene, Vincent Milay, Mandy Rose Nichols, Jessica Robins, Cammi Smith, Kevin Tanner, Karin Terry, Harry Turpin, and Emily Welter Setting: LONDON Time: TODAY TWO ACTS ONE 15 MINUTE INTERMISSION Running Time: 2:45 Please turn off all cell phones during the show. The videotaping or photographing of this production is strictly prohibited. WARNINGS BLOOD, VIOLENCE, GUN SHOTS, & MEAT PIES “Sweeney Todd” is presented by special arrangement with Musical Theatre International (MTI). All authorized performance materials are also supplied by MTI. www.MTISHOWS.com Director’s Note "In this day and age it is so very easily to be #literallyobsessed with the #blessed lives that we all watch through our instagrams and behind the safety of a screen. #nofilter It's easy to turn something into what you want it to be with enough of a filter. It's easy to get swept up in a trend. #fomo #yolo The tale of Sweeney Todd is in direct result of obsession, and possession, and seeing what you want to see. #lemmestopforaselfie A person of power wanting what they can't have, though they have no concept of what that "thing" is or means, destroys lives to get to his idea. -

Cannibal and Transcendence Narratives in Les Misérables, Sweeney Todd, and Interview with the Vampire

Cannibal and Transcendence Narratives in Les Misérables, Sweeney Todd, and Interview with the Vampire Judith Wilt (Boston College, Massachusetts, USA) Abstract: This essay studies the interlocking cannibal and transcendence plotlines supplied by three Victorian texts to three neo-Victorian works, two of them musicals, and one of them a key twentieth-century reworking of perhaps the original nineteenth-century cannibal narrative, the vampire legend. Alain Boublil and Claude-Michel Schönberg’s Les Misérables (1985) and Stephen Sondheim and Hugh Wheeler’s Sweeney Todd (1979) theatricalise this interlocking of narratives in surprisingly similar ways: Anne Rice’s Interview with the Vampire (1976) stages the cannibal and the transcendent impulses in a series of climaxes in and around the Théâtre des Vampires in Paris. Both the musicals and the novel break their deliberately theatrical frames in challenges to their audiences, raising in their similar ways the nineteenth-century question whether one can be Victorian without being a Romantic, and the twentieth-century question how one can be ‘neo’ as well as ‘Victorian’. Keywords: cannibal, The French Lieutenant’s Woman, Interview with the Vampire, Les Misérables, musicals, punishment, revolution, Sweeney Todd, theatre, transcendence. ***** When I went to graduate school in the 1960s I decided to be a Victorianist, because I felt like a Victorian. When John Fowles’s The French Lieutenant’s Woman (1969) came out shortly thereafter, I saw I could be a neo-Victorianist too. I fell in love with the musicals Les Misérables (1985), by Alain Boublil and Claude-Michel Schönberg, and Sweeney Todd (1979), by Stephen Sondheim and Hugh Wheeler, in the 1980s, both of them, despite the fact that reviewers and later scholars seemed to fear and loathe the first and admire the second. -

Community Consolidated School District 46

Community Consolidated School District 46 Park School Campus/East & West 400 West Townline Road • Round Lake • Illinois • 60073 Phone 847.201.7010 Fax 847.201.1971 Craig Keer, Principal Vince Murray, Assistant Principal June 3, 2011 Dear Park School Parents and Guardians, We have two very exciting announcements in this week’s Wolf Pack Press of the school 2010-2011 school year. First, we are absolutely thrilled to announce that Mr. Matt Melamed will be the next principal of Park School Campus. Mr. Melamed was part of the Park School design team that helped open Park School Campus in 2007 and has a thorough understanding of the vision, commitment, and community of our neighborhood school. Mr. Melamed previously served as Park School Campus History Teacher and Activities Director from 2007 to 2009. Since 2009, Mr. Melamed has served as District 46’s Curriculum Coordinator where he has overseen the successful adoption of our new K-8 math curriculum, led the district’s K-8th Grade Curriculum Coordinating Council, and has been in charge of the district’s professional development plan. We are looking forward to an extended transition time and are confident that Mr. Melamed will be an outstanding leader of Park School for many years to come. We are also pleased to announce that Park School Campus is the recipient of The Blue Ribbon Lighthouse Award for 2011. Staff, students and parents were surveyed on nine essential components of effective schools and members of the Blue Ribbon team participated in a site visit. Strengths and areas for continuous improvement were outlined and addressed leading to Park School Campus meeting or exceeding the criteria of all nine categories.