A Cognitive Approach to Gestural Life in Stephen Sondheim's Musical Genres

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Drama Book Shop Became an Independent Store in 1923

SAVORING THE CLASSICAL TRADITION IN DRAMA ENGAGING PRESENTATIONS BY THE SHAKESPEARE GUILD I N P R O U D COLLABORATION WIT H THE NATIONAL ARTS CLUB THE PLAYERS, NEW YORK CITY THE ENGLISH-SPEAKING UNION SALUTING A UNIQUE INSTITUTION ♦ Monday, November 26 Founded in 1917 by the Drama League, the Drama Book Shop became an independent store in 1923. Since 2001 it has been located on West 40th Street, where it provides a variety of services to the actors, directors, producers, and other theatre professionals who work both on and off Broadway. Many of its employees THE PLAYERS are young performers, and a number of them take part in 16 Gramercy Park South events at the Shop’s lovely black-box auditorium. In 2011 Manhattan the store was recognized by a Tony Award for Excellence RECEPTION 6:30, PANEL 7:00 in the Theatre . Not surprisingly, its beneficiaries (among them Admission Free playwrights Eric Bogosian, Moises Kaufman, Lin-Manuel Reservations Requested Miranda, Lynn Nottage, and Theresa Rebeck), have responded with alarm to reports that high rents may force the Shop to relocate or close. Sharing that concern, we joined The Players and such notables as actors Jim Dale, Jeffrey Hardy, and Peter Maloney, and writer Adam Gopnik to rally support for a cultural treasure. DAKIN MATTHEWS ♦ Monday, January 28 We look forward to a special evening with DAKIN MATTHEWS, a versatile artist who is now appearing in Aaron Sorkin’s acclaimed Broadway dramatization of To Kill a Mockingbird. In 2015 Dakin portrayed Churchill, opposite Helen Mirren’s Queen Elizabeth II, in the NATIONAL ARTS CLUB Broadway transfer of The Audience. -

Into the Woods Is Presented Through Special Arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI)

PREMIER SPONSOR ASSOCIATE SPONSOR MEDIA SPONSOR Music and Lyrics by Book by Stephen Sondheim James Lapine June 28-July 13, 2019 Originally Directed on Broadway by James Lapine Orchestrations by Jonathan Tunick Original Broadyway production by Heidi Landesman Rocco Landesman Rick Steiner M. Anthony Fisher Frederic H. Mayerson Jujamcyn Theatres Originally produced by the Old Globe Theater, San Diego, CA. Scenic Design Costume Design Shoko Kambara† Megan Rutherford Lighting Design Puppetry Consultant Miriam Nilofa Crowe† Peter Fekete Sound Design Casting Director INTO The Jacqueline Herter Michael Cassara, CSA Woods Musical Director Choreographer/Associate Director Daniel Lincoln^ Andrea Leigh-Smith Production Stage Manager Production Manager Myles C. Hatch* Adam Zonder Director Michael Barakiva+ Into the Woods is presented through special arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI). All authorized performance materials are also supplied by MTI. www.MTIShows.com Music and Lyrics by Book by STEPHEN JAMES Directed by SONDHEIM LAPINE MICHAEL * Member of Actor’s Equity Association, † USA - Member of Originally directed on Broadway by James LapineBARAKIVA the Union of Professional Actors and United Scenic Artists Orchestrations by Jonathan Tunick Stage Managers in the United States. Local 829. ^ Member of American Federation of Musicians, + Local 802 or 380. CAST NARRATOR ............................................................................................................................................HERNDON LACKEY* CINDERELLA -

TRU Speak Program 021821 XS

THEATER RESOURCES UNLIMITED VIRTUAL BENEFIT PLAYBILL TRU SPEAK Hear Our Voices! An evening of awareness to benefit THEATER RESOURCES UNLIMITED executive producer Bob Ost associate producers Iben Cenholt and Joe Nelms benefit chair Sanford Silverberg plays produced by Jonathan Hogue, Stephanie Pope Lofgren, James Rocco, Claudia Zahn assistant to the producers Maureen Condon technical coordinator Iben Cenholt/RuneFilms editor-technologists Iben Cenholt/RuneFilms, Andrea Lynn Green, Carley Santori, Henry Garrou/Whitetree, LLC video editors Sam Berland/Play It Again Sam’s Video Productions, Joe Nelms art direction & graphics Gary Hughes casting by Jamibeth Margolis Casting Social Media Coordinator Jeslie Pineda featuring MAGGIE BAIRD • BRENDAN BRADLEY • BRENDA BRAXTON JIM BROCHU • NICK CEARLEY • ROBERT CUCCIOLI • ANDREA LYNN GREEN ANN HARADA • DICKIE HEARTS • CADY HUFFMAN • CRYSTAL KELLOGG WILL MADER • LAUREN MOLINA • JANA ROBBINS • REGINA TAYLOR CRYSTAL TIGNEY • TATIANA WECHSLER with Robert Batiste, Jianzi Colon-Soto, Gha'il Rhodes Benjamin, Adante Carter, Tyrone Hall, Shariff Sinclair, Taiya, and Stephanie Pope Lofgren as the Voice of TRU special appearances by JERRY MITCHELL • BAAYORK LEE • JAMES MORGAN • JILL PAICE TONYA PINKINS •DOMINIQUE SHARPTON • RON SIMONS HALEY SWINDAL • CHERYL WIESENFELD TRUSpeak VIP After Party hosted by Write Act Repertory TRUSpeak VIP After Party production and tech John Lant, Tamra Pica, Iben Cenholt, Jennifer Stewart, Emily Pierce Virtual Happy Hour an online musical by Richard Castle & Matthew Levine directed -

Little Shop of Horrors

PRESENTS LITTLE SHOP OF HORRORS Book and Lyrics by Music by HOWARD ASHMAN ALAN MENKEN Based on the film by Roger Corman Screenplay by Charles Griffith Directed by Bill Fennelly September 10 – October 16, 2016 Artistic Director | Chris Coleman LITTLE SHOP OF HORRORS Music by Book and Lyrics by ALAN MENKEN HOWARD ASHMAN Based on the film by Roger Corman Screenplay by Charles Griffith Directed by Bill Fennelly Music Supervisor Choreographer Scenic Designer Rick Lewis Kent Zimmerman Michael Schweikardt Costume Designer Lighting Designer Sound Designer Kathleen Geldard William C. Kirkham Casi Pacilio Original Vocal Original Orchestrations Fight Director Arrangements Robert Merkin John Armour Robert Billig Stage Manager Dance Captain Assistant Stage Manager Mark Tynan* Johari Nandi Mackey* JanineVanderhoff* Production Assistants New York Casting Local Casting Bailey Anne Maxwell Harriet Bass Brandon Woolley Stephen Kriz Gardner *Member of Actors’ Equity Association, the Union of Professional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States. CAST LIST Chiffon Johari Nandi Mackey* Crystal Alexis Tidwell* Ronnette Ebony Blake* Mushnik David Meyers* Audrey Gina Milo* Seymour Nick Cearley* Orin Jamison Stern* The Voice of Audrey II/Wino 1 Chaz Rose* Audrey II Manipulation Stephen Kriz Gardner *Member of Actors’ Equity Association, the Union of Professional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States. Co-produced with Cincinnati Playhouse in the Park, Blake Robison, Artistic Director, and Buzz Ward, Managing Director. Originally produced by the WPA Theatre (Kyle Renick, Producing Director). Originally produced at the Orpheum Theatre, New York City, by the WPA Theatre, David Geffen, Cameron Mackintosh and the Shubert Organization. Little Shop of Horrors was originally directed by Howard Ashman with musical staging by Edie Cowan. -

The Dark Side of the Tune: a Study of Villains

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2008 The Dark Side Of The Tune: A Study Of Villains Michael Biggs University of Central Florida Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Biggs, Michael, "The Dark Side Of The Tune: A Study Of Villains" (2008). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 3811. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/3811 THE DARK SIDE OF THE TUNE: A STUDY OF VILLAINS by MICHAEL FREDERICK BIGGS II B.A. California State University, Chico, 2004 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in the Department of Theatre in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2008 © 2008 Michael Biggs ii ABSTRACT On “championing” the villain, there is a naïve quality that must be maintained even though the actor has rehearsed his tragic ending several times. There is a subtle difference between “to charm” and “to seduce.” The need for fame, glory, power, money, or other objects of affection drives antagonists so blindly that they’ve no hope of regaining a consciousness about their actions. If and when they do become aware, they infrequently feel remorse. -

Desperate Housewives a Lot Goes on in the Strange Neighborhood of Wisteria Lane

Desperate Housewives A lot goes on in the strange neighborhood of Wisteria Lane. Sneak into the lives of five women: Susan, a single mother; Lynette, a woman desperately trying to b alance family and career; Gabrielle, an exmodel who has everything but a good m arriage; Bree, a perfect housewife with an imperfect relationship and Edie Britt , a real estate agent with a rocking love life. These are the famous five of Des perate Housewives, a primetime TV show. Get an insight into these popular charac ters with these Desperate Housewives quotes. Susan Yeah, well, my heart wants to hurt you, but I'm able to control myself! How would you feel if I used your child support payments for plastic surgery? Every time we went out for pizza you could have said, "Hey, I once killed a man. " Okay, yes I am closer to your father than I have been in the past, the bitter ha tred has now settled to a respectful disgust. Lynette Please hear me out this is important. Today I have a chance to join the human rac e for a few hours there are actual adults waiting for me with margaritas. Loo k, I'm in a dress, I have makeup on. We didn't exactly forget. It's just usually when the hostess dies, the party is off. And I love you because you find ways to compliment me when you could just say, " I told you so." Gabrielle I want a sexy little convertible! And I want to buy one, right now! Why are all rich men such jerks? The way I see it is that good friends support each other after something bad has happened, great friends act as if nothing has happened. -

Sweeney Todd the Demon Barber of Fleet Street a Musical Thriller

Reboot Theatre Company Presents Sweeney Todd The Demon Barber of Fleet Street A Musical Thriller Music and Lyrics by Stephen Sondheim Book by Hugh Wheeler From an adaptation by Christopher Bond. Originally directed on Broadway by Harold Prince. Orchestrations by Jonathan Tunic. Originally produced on Broadway by Richard Barr, Charles Woodward, Robert Fryer, Mary Lea Johnson, Martin Richards in association with Dean and Judy Manos Directed Music Direction by by Julia Griffin Aimee Hong With (In alphabetical order) Brittany Allyson, Justine Davis, Kylee Gano, Alyssa Keene, Vincent Milay, Mandy Rose Nichols, Jessica Robins, Cammi Smith, Kevin Tanner, Karin Terry, Harry Turpin, and Emily Welter Setting: LONDON Time: TODAY TWO ACTS ONE 15 MINUTE INTERMISSION Running Time: 2:45 Please turn off all cell phones during the show. The videotaping or photographing of this production is strictly prohibited. WARNINGS BLOOD, VIOLENCE, GUN SHOTS, & MEAT PIES “Sweeney Todd” is presented by special arrangement with Musical Theatre International (MTI). All authorized performance materials are also supplied by MTI. www.MTISHOWS.com Director’s Note "In this day and age it is so very easily to be #literallyobsessed with the #blessed lives that we all watch through our instagrams and behind the safety of a screen. #nofilter It's easy to turn something into what you want it to be with enough of a filter. It's easy to get swept up in a trend. #fomo #yolo The tale of Sweeney Todd is in direct result of obsession, and possession, and seeing what you want to see. #lemmestopforaselfie A person of power wanting what they can't have, though they have no concept of what that "thing" is or means, destroys lives to get to his idea. -

P E R F O R M I N G

PERFORMING & Entertainment 2019 BOOK CATALOG Including Rowman & Littlefield and Imprints of Globe Pequot CONTENTS Performing Arts & Entertainment Catalog 2019 FILM & THEATER 1 1 Featured Titles 13 Biography 28 Reference 52 Drama 76 History & Criticism 82 General MUSIC 92 92 Featured Titles 106 Biography 124 History & Criticism 132 General 174 Order Form How to Order (Inside Back Cover) Film and Theater / FEATURED TITLES FORTHCOMING ACTION ACTION A Primer on Playing Action for Actors By Hugh O’Gorman ACTION ACTION Acting Is Action addresses one of the essential components of acting, Playing Action. The book is divided into two parts: A Primer on Playing Action for Actors “Context” and “Practice.” The Context section provides a thorough examination of the theory behind the core elements of Playing Action. The Practice section provides a step-by-step rehearsal guide for actors to integrate Playing Action into their By Hugh O’Gorman preparation process. Acting Is Action is a place to begin for actors: a foundation, a ground plan for how to get started and how to build the core of a performance. More precisely, it provides a practical guide for actors, directors, and teachers in the technique of Playing Action, and it addresses a niche void in the world of actor training by illuminating what exactly to do in the moment-to-moment act of the acting task. March, 2020 • Art/Performance • 184 pages • 6 x 9 • CQ: TK • 978-1-4950-9749-2 • $24.95 • Paper APPLAUSE NEW BOLLYWOOD FAQ All That’s Left to Know About the Greatest Film Story Never Told By Piyush Roy Bollywood FAQ provides a thrilling, entertaining, and intellectually stimulating joy ride into the vibrant, colorful, and multi- emotional universe of the world’s most prolific (over 30 000 film titles) and most-watched film industry (at 3 billion-plus ticket sales). -

From Real Time to Reel Time: the Films of John Schlesinger

From Real Time to Reel Time: The Films of John Schlesinger A study of the change from objective realism to subjective reality in British cinema in the 1960s By Desmond Michael Fleming Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2011 School of Culture and Communication Faculty of Arts The University of Melbourne Produced on Archival Quality Paper Declaration This is to certify that: (i) the thesis comprises only my original work towards the PhD, (ii) due acknowledgement has been made in the text to all other material used, (iii) the thesis is fewer than 100,000 words in length, exclusive of tables, maps, bibliographies and appendices. Abstract The 1960s was a period of change for the British cinema, as it was for so much else. The six feature films directed by John Schlesinger in that decade stand as an exemplar of what those changes were. They also demonstrate a fundamental change in the narrative form used by mainstream cinema. Through a close analysis of these films, A Kind of Loving, Billy Liar, Darling, Far From the Madding Crowd, Midnight Cowboy and Sunday Bloody Sunday, this thesis examines the changes as they took hold in mainstream cinema. In effect, the thesis establishes that the principal mode of narrative moved from one based on objective realism in the tradition of the documentary movement to one which took a subjective mode of narrative wherein the image on the screen, and the sounds attached, were not necessarily a record of the external world. The world of memory, the subjective world of the mind, became an integral part of the narrative. -

To Hold As T'were the Mirror up to Hate: Terrence Mcnally's Response to the Christian Right in Corpus Christi

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English 8-6-2007 To Hold as T'were the Mirror Up to Hate: Terrence McNally's Response to the Christian Right in Corpus Christi Richard Kimberly Sisson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Sisson, Richard Kimberly, "To Hold as T'were the Mirror Up to Hate: Terrence McNally's Response to the Christian Right in Corpus Christi." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2007. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/20 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TO HOLD AS T’WERE THE MIRROR UP TO HATE: TERRENCE MCNALLY’S RESPONSE TO THE CHRISTIAN RIGHT IN CORPUS CHRISTI by RICHARD KIMBERLY SISSON Under the direction of Matthew C. Roudané ABSTRACT In 1998, the Manhattan Theatre Club’s staging of Terrence McNally’s play Corpus Christi ignited protest and virulent condemnation from various religious and politically conservative groups which eventually led to the cancellation of the play’s production. This led to a barrage of criticism from the national theatre, gay, and civil rights communities and free speech advocates, including the ACLU and PEN, which issued a press releases about the cancellation that decried censorship and acquiescence by the theatre to neo-conservative religiously political groups. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

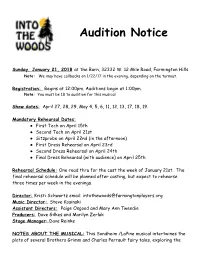

Audition Notice

Audition Notice Sunday, January 21, 2018 a t the Barn, 32332 W. 12 Mile Road, Farmington Hills Note: We may have callbacks on 1/22/17 in the evening, depending on the turnout. Registration: Begins at 12:00pm. Auditions begin at 1:00pm. Note: You must be 18 to audition for this musical. Show dates: April 27, 28, 29, May 4, 5, 6, 11, 12, 13, 17, 18, 19. Mandatory Rehearsal Dates: ● First Tech on April 15th ● Second Tech on April 21st ● Sitzprobe on April 22nd (in the afternoon) ● First Dress Rehearsal on April 23rd ● Second Dress Rehearsal on April 24th ● Final Dress Rehearsal (with audience) on April 25th Rehearsal Schedule: One read thru for the cast the week of January 21st. The final rehearsal schedule will be planned after casting, but expect to rehearse three times per week in the evenings. Director: Kristi Schwartz email: [email protected] Music Director: Steve Kosinski Assistant Directors: Paige Osgood and Mary Ann Tweedie Producers: D ave Gilkes and Marilyn Zerlak Stage Manager: D ave Reinke NOTES ABOUT THE MUSICAL: This Sondheim /LaPine musical intertwines the plots of several Brothers Grimm and Charles Perrault fairy tales, exploring the consequences of the characters‛ wishes and dreams. When a childless baker and his wife embark on a quest to begin a family, they interact with storybook characters from “Little Red Riding Hood”, “Jack and the Beanstalk”, “Rapunzel”, and “Cinderella”, during their journey. Will their wishes come true? And do they really want them to? Preparing for Auditions There will be two parts to the audition process for I nto the Woods .