1 Published in James Goodwin, Ed., a Guide to International Art Markets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Auckland City Art Gallery

Frances Hodgkins 14 auckland city art gallery modern european paintings in new Zealand This exhibition brings some of the modern European paintings in New Zealand together for the first time. The exhibition is small largely because many galleries could not spare more paintings from their walls and also the conditions of certain bequests do not permit loans. Nevertheless, the standard is reasonably high. Chronologically the first modern movement represented is Impressionism and the latest is Abstract Expressionism, while the principal countries concerned are Britain and France. Two artists born in New Zealand are represented — Frances Hodgkins and Raymond Mclntyre — the former well known, the latter not so well as he should be — for both arrived in Europe before 1914 when the foundations of twentieth century painting were being laid and the earlier paintings here provide some indication of the milieu in which they moved. It is hoped that this exhibition may help to persuade the public that New Zealand is not devoid of paintings representing the serious art of this century produced in Europe. Finally we must express our sincere thanks to private owners and public galleries for their generous response to requests for loans. P.A.T. June - July nineteen sixty the catalogue NOTE: In this catalogue the dimensions of the paintings are given in inches, height before width JANKEL ADLER (1895-1949) 1 SEATED FIGURE Gouache 24} x 201 Signed ADLER '47 Bishop Suter Art Gallery, Nelson Purchased by the Trustees, 1956 KAREL APPEL (born 1921) Dutch 2 TWO HEADS (1958) Gouache 243 x 19i Signed K APPEL '58 Auckland City Art Gallery Presented by the Contemporary Art Society, 1959 JOHN BRATBY (born 1928) British 3 WINDOWS (1957) Oil on canvas 48x144 Signed BRATBY JULY 1957 Auckland City Art Gallery Presented by Auckland Gallery Associates, 1958 ANDRE DERAIN (1880-1954) French 4 LANDSCAPE Oil on canvas 21x41 J Signed A. -

Flemish Art 1880–1930

COMING FLEMISH ART 1880–1930 EDITOR KATHARINA VAN CAUTEREN HOME WITH ESSAYS BY ANNE ADRIAENS-PANNIER PATRICK BERNAUW PIET BOYENS KLAAS COULEMBIER JOHAN DE SMET MARK EYSKENS DAVID GARIFF LEEN HUET FERNAND HUTS PAUL HUVENNE PETER PAUWELS CONSTANTIJN PETRIDIS NIELS SCHALLEY HERWIG TODTS KATHARINA VAN CAUTEREN LUC VAN CAUTEREN SVEN VAN DORST CATHÉRINE VERLEYSEN Hubert Malfait Home from the Fields, 1923-1924 Oil on canvas, 120 × 100 cm COURTESY OF FRANCIS MAERE FINE ARTS CONTENTS 7 PREFACE 211 JAMES ENSOR’S KATHARINA VAN CAUTEREN WHIMSICAL QUEST FOR BLISS HERWIG TODTS 9 PREFACE FERNAND HUTS 229 WOUTERS WRITINGS 13 THE ROOTS OF FLANDERS HERWIG TODTS KATHARINA VAN CAUTEREN 253 EDGARD TYTGAT. 65 AUTHENTIC, SOUND AND BEAUTIFUL. ‘PEINTRE-IMAGIER’ THE RECEPTION OF LUC VAN CAUTEREN FLEMISH EXPRESSIONISM PAUL HUVENNE 279 CONSTANT PERMEKE. THE ETERNAL IN THE EVERYDAY 79 THE MOST FLEMISH FLEMINGS PAUL HUVENNE WRITE IN FRENCH PATRICK BERNAUW 301 GUST. DE SMET. PAINTER OF CONTENTMENT 99 A GLANCE AT FLEMISH MUSIC NIELS SCHALLEY BETWEEN 1890 AND 1930 KLAAS COULEMBIER 319 FRITS VAN DEN BERGHE. SURVEYOR OF THE DARK SOUL 117 FLEMISH BOHÈME PETER PAUWELS LEEN HUET 339 ‘PRIMITIVISM’ IN BELGIUM? 129 THE BELGIAN LUMINISTS IN AFRICAN ART AND THE CIRCLE OF EMILE CLAUS FLEMISH EXPRESSIONISM JOHAN DE SMET CONSTANTIJN PETRIDIS 149 BENEATH THE SURFACE. 353 LÉON SPILLIAERT. THE ART OF THE ART OF THE INDEFINABLE GUSTAVE VAN DE WOESTYNE ANNE ADRIAENS-PANNIER SVEN VAN DORST 377 THE EXPRESSIONIST IMPULSE 175 VALERIUS DE SAEDELEER. IN MODERN ART THE SOUL OF THE LANDSCAPE DAVID GARIFF PIET BOYENS 395 DOES PAINTING HAVE BORDERS? 195 THE SCULPTURE OF MARK EYSKENS GEORGE MINNE CATHÉRINE VERLEYSEN 6 PREFACE Dear Reader, 7 Just so you know, this book is not the Bible. -

Ensor to Permeke

06 • 10 • 2015 Ensor to Permeke A PASSION FOR BELGIAN ART BA cata Ensor 167x242 22/07/15 10:00 Page 1 ENTE VEILING mardi - dinsdag 06 • 10 • 2015 - 19.00 Ensor to Permeke A PASSION FOR BELGIAN ART 7 – 9, RUE ERNEST ALLARDSTRAAT (SABLON-ZAVEL) • B-1000 BRUXELLES - BRUSSEL T. +32 (0)2 511 53 24 • [email protected] WWW.BA-AUCTIONS.COM BA cata Ensor 167x242 22/07/15 10:00 Page 2 BA cata Ensor 167x242 22/07/15 10:00 Page 3 BA cata Ensor 167x242 22/07/15 10:00 Page 4 La collection Eric Drossart, le reflet d’une passion Lorsque je disputais la Coupe Davis dans les années soixante, et même au début de ma carrière chez Mc Cormack, je ne me connais- sais aucune affinité particulière avec l’Art. Tout a commencé lors de mon installation à Londres, au début des années quatre-vingt. J’y ai découvert le monde des galeries d’art, des ventes aux enchères et très vite cet univers fascinant s’est imposé à moi comme une évidence et devint une passion. Mon intérêt pour l’art belge, essentiellement celui de la fin du 19e siècle et du début du 20e siècle, répondait parfaitement à ma sensibilité naissante et à mon sentiment d’exilé. Dès 1991 j’ai donc commencé avec les encouragements de ma mère, qui adorait fouiner, à rechercher et à acquérir des œuvres d’artistes belges de cette période. Peu de temps après, j’ai eu la chance de rencontrer Sabine Taevernier qui est devenue, et qui est encore aujourd’hui, ma conseillère. -

Faculteit Letteren En Wijsbegeerte Vakgroep Kunst-, Muziek- En Theaterwetenschappen Academiejaar 2009-2010 Eerste Examenperiode

Faculteit Letteren en Wijsbegeerte Vakgroep Kunst-, Muziek- en Theaterwetenschappen Academiejaar 2009-2010 Eerste Examenperiode Artistieke afbeeldingen van het amusementsleven in het oeuvre van Gustave De Smet, Edgard Tytgat en Floris Jespers binnen het sociaal culturele spanningsveld van de jaren twintig Scriptie neergelegd tot het behalen van de graad van Master in de Kunstwetenschappen, Optie Beeldende Kunst door Willem Coppejans Promotor: Prof. Dr. Claire Van Damme INHOUDSTAFEL Voorwoord …………………………………………………………………………………………5 Status Quaestionis …………………………………………………………………………………6 1. Situering van de protagonisten in de jaren twintig en hun relatie ten opzichte van het amusementsleven ………………………………………………...…13 1.1 Gustave De Smet………………………………………………………………………………. 13 1.2 Edgard Tytgat………………………………………………………………………………….. 14 1.3 Floris Jespers…………………………………………………………………………………... 16 1.4 Besluit………………………………………………………………………………………….. 17 2 Sociaal historische invloed op het veelvuldige voorkomen van de thematiek van het amusementsleven in de Vlaamse kunst van de jaren twintig …………….. 18 2.1 Historische schets: het amusementsleven in de jaren twintig………………………………….. 18 2.1.1 De dolle jaren twintig?…………………………………………………………………………. 18 2.1.2 Bloei van de amusementscultuur ondanks een bar economisch klimaat………………………. 19 2.1.3 Het amusementsleven van de jaren twintig: voor elk wat wils………………………………... 20 2.1.3.1 Kermis…………………………………………………………………………………………. 20 2.1.3.2 Circus………………………………………………………………………………………….. 20 2.1.3.3 Kusttoerisme…………………………………………………………………………………… 21 2.1.3.4 -

Gallery Notes

Gallery Notes JOHN MITCHELL FINE PAINTINGS LONDON September 2011 Gallery Notes is published to acquaint readers with the paintings and drawings offered for sale by JOHN MITCHELL FINE PAINTINGS 44 O LD BOND STREET , L ONDON W1S 4GB TEL : +44 (0)20 7493 7567 www.johnmitchell.net FOREWORD In February we held our sixth James Hart Dyke exhibition, which proved to be nothing less than a sensation, even by the standards of the modern art world. In a striking departure from James’s previous work , A Year with MI6 brought together seventy-five paintings and drawings which had been commissioned from him to commemorate the centenary of the Secret Intelligence Service. The fact that James had spent most of the previous eighteen months working within MI6 heightened the media’s interest in the exhibition, and culminated in its being reviewed for over two minutes on the ten o’clock news. The artist gained considerable insight into the day-to-day workings of the Service, and his observations were reflected in his direct yet enigmatic pictures. That so many of them sold, so quickly and often to new collectors, is a tribute to James’s artistic accomplishment rather than to the éclat of the subject matter. We look forward to hosting his next exhibition of landscape paintings soon. This summer has seen our participation (simultaneously) in Masterpiece and in Master Paintings Week . The organisers of the former are to be congratulated on their achievement in setting up the prestigious and stylish art fair that London has conspicuously lacked for a long time, and even after only two years it looks set to become an established fixture of the social season and of the international art world calendar. -

Continuum 119 a Belgian Art Perspective

CONTINUUM 119 A BELGIAN ART PERSPECTIVE OFF-PROGRAM GROUP SHOW 15/04/19 TO 31/07/19 Art does not belong to anyone, it usually passes on from one artist to the next, from one viewer to the next. We inherit it from the past when it served as a cultural testimony to who we were, and we share it with future generations, so they may understand who we are, what we fear, what we love and what we value. Over centuries, civilizations, societies and individuals have built identities around art and culture. This has perhaps never been more so than today. As an off-program exhibition, I decided to invite five Belgian artists whose work I particularly like, to answer back with one of their own contemporary works to a selection of older works that helped build my own Belgian artistic identity. In no way do I wish to suggest that their current work is directly inspired by those artists they will be confronted with. No, their language is mature and singular. But however unique it may be, it can also be looked at in the context of the subtle evolution from their history of art, as mutations into new forms that better capture who these artists are, and the world they live in. Their work can be experienced within an artistic continuum, in which pictorial elements are part of an inheritance, all the while remaining originally distinct. On each of these Belgian artists, I imposed a work from the past, to which they each answered back with a recent work of their own. -

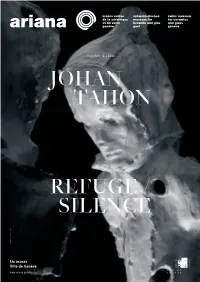

G Er T Ja Nv an R Oo Ij

28.9.2019–5.4.2020 JOHAN TAHON REFUGE / SILENCE Photographie : Gert Jan van Rooij Press Kit 16 September 2019 Johan Tahon REFUGE/SILENCE Musée Ariana, 28 September 2019 – 5 April 2020 Press visits on request only Exhibition preview Friday 27 September 2019 at 6pm Musée Ariana Swiss Museum for Ceramics and Glass 10, avenue de la Paix 1202 Geneva - Switzerland Press kit available at “Presse”: www.ariana-geneve.ch Visuals, photos on request: [email protected] Un musée Ville de Genève www.ariana-geneve.ch Johan Tahon REFUGE/SILENCE Musée Ariana, 28 September 2019 – 5 April 2020 CONTENTS Johan Tahon. REFUGE/SILENCE p. 3 Biography of Johan Tahon p. 4 Events p. 8 Practical information p. 9 2 Johan Tahon REFUGE/SILENCE Musée Ariana, 28 September 2019 – 5 April 2020 J OHAN T AHON. REFUGE/SILENCE The Musée Ariana is proud to present Johan Tahon. REFUGE/SILENCE, in partnership with the Kunstforum gallery in Solothurn, from 28 September 2019 to 5 April 2020 in the space dedicated to contemporary creation. Johan Tahon, internationally renowned Belgian artist, is exhibiting a strong and committed body of work that reveals his deep connection with the ceramic medium. In the space devoted to contemporary creation, visitors enter a mystical world inhabited by hieratic monks, leading them into a second gallery where, in addition to the figures, pharmacy jars or albarelli are displayed. A direct reference to the history of faience, the ointments, powders and medicines contained in such vessels were intended to heal both body and soul. A sensitive oeuvre reflecting the human condition Johan Tahon’s oeuvre evolves in an original and individual way. -

Untitled for the Exhibition Body Talk Presented at WIELS, Brussels 2015

1 Inhoudstafel Inhoudstafel ............................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Feast of Fools. Bruegel herontdekt ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Meer dan alleen een tentoonstelling .................................................................................................................................... 6 Titel ........................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Kunstwerken ‘Feast of Fools. Bruegel herontdekt’............................................................................................................ 8 Bruiklenen ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 8 1. Introductie ............................................................................................................................................................................ 8 2. Back to the Roots ............................................................................................................................................................ 8 3. Everybody Hurts ............................................................................................................................................................. -

NINETEENTH-Century EUROPEAN PAINTINGS at the STERLING

Introduction Introduction Sterling and Francine clark art inStitute | WilliamStoWn, massachuSettS NINETEENTH-CENTURY EUROPEAN PAINTINGS diStributed by yale univerSity Press | NeW haven and london AT THE STERLING AND FRANCINE CLARK ART INSTITUTE VOLUME TWO Edited by Sarah Lees With an essay by Richard Rand and technical reports by Sandra L. Webber With contributions by Katharine J. Albert, Philippe Bordes, Dan Cohen, Kathryn Calley Galitz, Alexis Goodin, Marc Gotlieb, John House, Simon Kelly, Richard Kendall, Kathleen M. Morris, Leslie Hill Paisley, Kelly Pask, Elizabeth A. Pergam, Kathryn A. Price, Mark A. Roglán, James Rosenow, Zoë Samels, and Fronia E. Wissman 4 5 Nineteenth-Century European Paintings at the Sterling and Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Francine Clark Art Institute is published with the assistance of the Getty Foundation and support from the National Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute. Endowment for the Arts. Nineteenth-century European paintings at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute / edited by Sarah Lees ; with an essay by Richard Rand and technical reports by Sandra L. Webber ; with contributions by Katharine J. Albert, Philippe Bordes, Dan Cohen, Kathryn Calley Galitz, Alexis Goodin, Marc Gotlieb, John House, Simon Kelly, Richard Kendall, Kathleen M. Morris, Leslie Hill Paisley, Kelly Pask, Elizabeth A. Produced by the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute Pergam, Kathryn A. Price, Mark A. Roglán, James Rosenow, 225 South Street, Williamstown, Massachusetts 01267 Zoë Samels, Fronia E. Wissman. www.clarkart.edu volumes cm Includes bibliographical references and index. Curtis R. Scott, Director of Publications ISBN 978-1-935998-09-9 (clark hardcover : alk. paper) — and Information Resources ISBN 978-0-300-17965-1 (yale hardcover : alk. -

The Art of the Metropolitan Museum of New York

tCbe Hrt of tbe flftetiopoUtan fIDuseum 3Bg tbe Same Butbor 2L XTbe art of tbe IRetberlanb (Balleriea Being a History of the Dutch School of Painting Illuminated and Demonstrated by Critical Descriptions of the Great Paintings in the many Galleries With 48 Illustrations. Price, $2.00 net £ L. C. PAGE & COMPANY New England Building, Boston, Mass. GIBBS - C HANNING PORTRAIT OF GEORGE WASHINGTON. By Gilbert Stuart. (See page 287) fje gtrt of iWetcopolitany 3*1 it scnut of 3Ul” Motfe & Giving a descriptive and critical account of its treasures, which represent the arts and crafts from remote antiquity to the present time. ^ By David C. Preyer, M. A. Author of “ The Art of the Netherland Galleries,” etc. Illustrated Boston L. C. Page & Company MDCCCC1 X Copyright, 1909 By L. C. Page & Company (incorporated) All rights reservea First Impression, November, 1909 Electrotyped and Printed at THE COLONIAL PRESS C.H . Simonas Sr Co., Boston U.S.A. , preface A visit to a museum with a guide book is not inspiring. Works of art when viewed should con- vey their own message, and leave their own im- pression. And yet, the deeper this impression, the more inspiring this message, the more anxious we will be for some further information than that conveyed by the attached tablet, or the catalogue reference. The aim of this book is to gratify this desire, to enable us to have a better understanding of the works of art exhibited in the Metropolitan Museum, to point out their corelation, and thus increase our appreciation of the treasures we have seen and admired. -

NINETEENTH-Century EUROPEAN PAINTINGS at the STERLING

Introduction Introduction Sterling and Francine clark art inStitute | WilliamStoWn, massachuSettS NINETEENTH-CENTURY EUROPEAN PAINTINGS diStributed by yale univerSity Press | NeW haven and london AT THE STERLING AND FRANCINE CLARK ART INSTITUTE VOLUME TWO Edited by Sarah Lees With an essay by Richard Rand and technical reports by Sandra L. Webber With contributions by Katharine J. Albert, Philippe Bordes, Dan Cohen, Kathryn Calley Galitz, Alexis Goodin, Marc Gotlieb, John House, Simon Kelly, Richard Kendall, Kathleen M. Morris, Leslie Hill Paisley, Kelly Pask, Elizabeth A. Pergam, Kathryn A. Price, Mark A. Roglán, James Rosenow, Zoë Samels, and Fronia E. Wissman 4 5 Nineteenth-Century European Paintings at the Sterling and Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Francine Clark Art Institute is published with the assistance of the Getty Foundation and support from the National Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute. Endowment for the Arts. Nineteenth-century European paintings at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute / edited by Sarah Lees ; with an essay by Richard Rand and technical reports by Sandra L. Webber ; with contributions by Katharine J. Albert, Philippe Bordes, Dan Cohen, Kathryn Calley Galitz, Alexis Goodin, Marc Gotlieb, John House, Simon Kelly, Richard Kendall, Kathleen M. Morris, Leslie Hill Paisley, Kelly Pask, Elizabeth A. Produced by the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute Pergam, Kathryn A. Price, Mark A. Roglán, James Rosenow, 225 South Street, Williamstown, Massachusetts 01267 Zoë Samels, Fronia E. Wissman. www.clarkart.edu volumes cm Includes bibliographical references and index. Curtis R. Scott, Director of Publications ISBN 978-1-935998-09-9 (clark hardcover : alk. paper) — and Information Resources ISBN 978-0-300-17965-1 (yale hardcover : alk. -

Heritage Days 14 & 15 Sept

HERITAGE DAYS 14 & 15 SEPT. 2019 A PLACE FOR ART 2 ⁄ HERITAGE DAYS Info Featured pictograms Organisation of Heritage Days in Brussels-Capital Region: Urban.brussels (Regional Public Service Brussels Urbanism and Heritage) Clock Opening hours and Department of Cultural Heritage dates Arcadia – Mont des Arts/Kunstberg 10-13 – 1000 Brussels Telephone helpline open on 14 and 15 September from 10h00 to 17h00: Map-marker-alt Place of activity 02/432.85.13 – www.heritagedays.brussels – [email protected] or starting point #jdpomd – Bruxelles Patrimoines – Erfgoed Brussel The times given for buildings are opening and closing times. The organisers M Metro lines and stops reserve the right to close doors earlier in case of large crowds in order to finish at the planned time. Specific measures may be taken by those in charge of the sites. T Trams Smoking is prohibited during tours and the managers of certain sites may also prohibit the taking of photographs. To facilitate entry, you are asked to not B Busses bring rucksacks or large bags. “Listed” at the end of notices indicates the date on which the property described info-circle Important was listed or registered on the list of protected buildings or sites. information The coordinates indicated in bold beside addresses refer to a map of the Region. A free copy of this map can be requested by writing to the Department sign-language Guided tours in sign of Cultural Heritage. language Please note that advance bookings are essential for certain tours (mention indicated below the notice). This measure has been implemented for the sole Projects “Heritage purpose of accommodating the public under the best possible conditions and that’s us!” ensuring that there are sufficient guides available.