Evidence from Cunningham

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Members, Vol 25

The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia House of Representatives List of Members Forty Fourth Parliament Volume 25 - 10 August 2015 Name Electorate & Party Electorate office address, telephone and facsimile Parliament House State / Territory numbers & other office details where applicable telephone & facsimile numbers Abbott, The Hon Anthony John Warringah, LP Level 2, 17 Sydney Road (PO Box 450), Manly Tel: (02) 6277 7700 (Tony) NSW NSW 2095 Fax: (02) 6273 4100 Prime Minister Tel : (02) 9977 6411, Fax : (02) 9977 8715 Albanese, The Hon Anthony Grayndler, ALP 334A Marrickville Road, Marrickville NSW 2204 Tel: (02) 6277 4664 Norman NSW Tel : (02) 9564 3588, Fax : (02) 9564 1734 Fax: (02) 6277 8532 E-mail: [email protected] Alexander, Mr John Gilbert Bennelong, LP Suite 1, 44 - 46 Oxford St (PO Box 872), Epping Tel: (02) 6277 4804 OAM NSW NSW 2121 Fax: (02) 6277 8581 Tel : (02) 9869 4288, Fax : (02) 9869 4833 E-mail: [email protected] Andrews, The Hon Karen Lesley McPherson, LP Ground Floor The Point 47 Watts Drive (PO Box 409), Tel: (02) 6277 4360 Parliamentary Secretary to the Qld Varsity Lakes Qld 4227 Fax: (02) 6277 8462 Minister for Industry and Science Tel : (07) 5580 9111, Fax : (07) 5580 9700 E-mail: [email protected] Andrews, The Hon Kevin James Menzies, LP 1st Floor 651-653 Doncaster Road (PO Box 124), Tel: (02) 6277 7800 Minister for Defence Vic Doncaster Vic 3108 Fax: (02) 6273 4118 Tel : (03) 9848 9900, Fax : (03) 9848 2741 E-mail: [email protected] Baldwin, The Hon Robert Charles Paterson, -

Activities & Achievements

April-June 2016 April-June 2016 AUSTRALIAN CHAMBER MEMBERS: BUSINESS SA | CANBERRA BUSINESS CHAMBER | CHAMBER OF COMMERCE Activities & NORTHERN TERRITORY | CHAMBER OF COMMERCE & INDUSTRY QUEENSLAND | CHAMBER OF COMMERCE & INDUSTRY WESTERN AUSTRALIA | NEW SOUTH WALES BUSINESS CHAMBER | TASMANIAN CHAMBER OF Achievements COMMERCE & INDUSTRY | VICTORIAN CHAMBER OF COMMERCE & INDUSTRY April-June 2016 NATIONAL INDUSTRY ASSOCIATION MEMBERS: ACCORD – HYGIENE, COSMETIC & SPECIALTY PRODUCTS INDUSTRY | AGED AND COMMUNITY SERVICES AUSTRALIA | AIR CONDITIONING & MECHANICAL CONTRACTORS ASSOCIATION | ASSOCIATION OF FINANCIAL ADVISERS | ASSOCIATION OF INDEPENDENT SCHOOLS OF NSW | AUSTRALASIAN PIZZA ASSOCIATION | AUSTRALIAN SUBSCRIPTION TELEVISION AND RADIO ASSOCIATION | Major Activities AUSTRALIAN BEVERAGES COUNCIL LIMITED | AUSTRALIAN DENTAL ASSOCIATION | AUSTRALIAN DENTAL CEO: James Pearson and Jenny Lambert (acting) INDUSTRY ASSOCIATION | AUSTRALIAN FEDERATION OF EMPLOYERS & INDUSTRIES | AUSTRALIAN This quarter we welcomed James Pearson as our new Chief Executive Officer. James has previously served as a senior FEDERATION OF TRAVEL AGENTS | AUSTRALIAN FOOD & GROCERY COUNCIL | AUSTRALIAN GIFT AND HOMEWARES executive at Shell Australia and CEO of the Chamber of Commerce ASSOCIATION | AUSTRALIAN HOTELS ASSOCIATION | AUSTRALIAN INTERNATIONAL AIRLINES OPERATIONS and Industry Western Australia, and has also gained experience at Australian Petroleum Production & Exploration Association and the GROUP | AUSTRALIAN MADE CAMPAIGN LIMITED | AUSTRALIAN MINES & -

Senator the Hon Concetta Fierravanti-Wells Hon Sharon Bird

Senator the Hon Concetta Hon Sharon Bird MP Fierravanti-Wells Federal Member for Cunningham Liberal Senator for New South Wales Stephen Jones MP Federal Member for Whitlam Senator the Hon Marise Payne Minister for Women M1 49, Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 Senator the Hon Anne Ruston Minister for Families and Social Services MG 60, Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 Dear Ministers, We are writing to support the Illawarra Women’s Health Centre’s proposal to establish a community- led first-in-Australia Domestic and Family Violence Trauma Recovery Centre. We strongly support this proposal. The Centre, an evidence based multi sectoral integrated service will transform domestic and family violence support services. Domestic and family violence is a major public health issue. Approximately one in six women in Australia have experienced physical and/or sexual violence by a current or previous partner. The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare reports that domestic violence is the greatest health risk factor for women aged 25 to 44. The impact of violence is substantial and long-lasting. Experiences of family and domestic violence are linked to poor mental and physical health outcomes, which can persist long after the violence has ceased. Moreover, women affected by family and domestic violence often face legal and financial challenges, which can lead to poverty and homelessness. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Complex PTSD are a very real outcome for women and children who have been exposed to family and domestic violence and abuse. Analysis from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women's Health shows that women who have untreated trauma or PTSD spend a minimum of 10% more per year on General Practitioners alone. -

The Rise of the Australian Greens

Parliament of Australia Department of Parliamentary Services Parliamentary Library Information, analysis and advice for the Parliament RESEARCH PAPER www.aph.gov.au/library 22 September 2008, no. 8, 2008–09, ISSN 1834-9854 The rise of the Australian Greens Scott Bennett Politics and Public Administration Section Executive summary The first Australian candidates to contest an election on a clearly-espoused environmental policy were members of the United Tasmania Group in the 1972 Tasmanian election. Concerns for the environment saw the emergence in the 1980s of a number of environmental groups, some contested elections, with successes in Western Australia and Tasmania. An important development was the emergence in the next decade of the Australian Greens as a unified political force, with Franklin Dam activist and Tasmanian MP, Bob Brown, as its nationally-recognised leader. The 2004 and 2007 Commonwealth elections have resulted in five Australian Green Senators in the 42nd Parliament, the best return to date. This paper discusses the electoral support that Australian Greens candidates have developed, including: • the emergence of environmental politics is placed in its historical context • the rise of voter support for environmental candidates • an analysis of Australian Greens voters—who they are, where they live and the motivations they have for casting their votes for this party • an analysis of the difficulties such a party has in winning lower house seats in Australia, which is especially related to the use of Preferential Voting for most elections • the strategic problems that the Australian Greens—and any ‘third force’—have in the Australian political setting • the decline of the Australian Democrats that has aided the Australian Greens upsurge and • the question whether the Australian Greens will ever be more than an important ‘third force’ in Australian politics. -

The Hon Bill Shorten Mp Shadow Ministry

THE HON BILL SHORTEN MP Leader of the Opposition Member for Maribyrnong SHADOW MINISTRY TITLE SHADOW MINISTER Leader of the Opposition Hon Bill Shorten MP Shadow Minister Assisting the Leader for Science Senator the Hon Kim Carr Shadow Minister Assisting the Leader for Small Business Hon Bernie Ripoll MP Shadow Parliamentary Secretary for Small Business Julie Owens MP Shadow Cabinet Secretary Senator the Hon Jacinta Collins Shadow Parliamentary Secretary to the Leader of the Opposition Shadow Parliamentary Secretary to the Leader of the Opposition Hon Michael Danby MP Shadow Parliamentary Secretary to the Leader of the Opposition Dr Jim Chalmers MP Deputy Leader of the Opposition Hon Tanya Plibersek MP Shadow Minister for Foreign Affairs and International Development Shadow Minister for Women Senator Claire Moore Manager of Opposition Business (Senate) Shadow Minister for the Centenary of ANZAC Senator the Hon Don Farrell Shadow Parliamentary Secretary for Foreign Affairs Hon Matt Thistlethwaite MP Leader of the Opposition in the Senate Senator the Hon Penny Wong Shadow Minister for Trade and Investment Shadow Parliamentary Secretary for Trade and Investment Dr Jim Chalmers MP Deputy Leader of the Opposition in the Senate Senator the Hon Stephen Conroy Shadow Minister for Defence Shadow Assistant Minister for Defence Hon David Feeney MP Shadow Minister for Veterans’ Affairs Senator the Hon Don Farrell Shadow Parliamentary Secretary for Defence Gai Brodtmann MP Shadow Minister for Infrastructure and Transport Hon Anthony Albanese MP Shadow -

Independents in Australian Parliaments

The Age of Independence? Independents in Australian Parliaments Mark Rodrigues and Scott Brenton* Abstract Over the past 30 years, independent candidates have improved their share of the vote in Australian elections. The number of independents elected to sit in Australian parliaments is still small, but it is growing. In 2004 Brian Costar and Jennifer Curtin examined the rise of independents and noted that independents ‘hold an allure for an increasing number of electors disenchanted with the ageing party system’ (p. 8). This paper provides an overview of the current representation of independents in Australia’s parliaments taking into account the most recent election results. The second part of the paper examines trends and makes observations concerning the influence of former party affiliations to the success of independents, the representa- tion of independents in rural and regional areas, and the extent to which independ- ents, rather than minor parties, are threats to the major parities. There have been 14 Australian elections at the federal, state and territory level since Costar and Curtain observed the allure of independents. But do independents still hold such an allure? Introduction The year 2009 marks the centenary of the two-party system of parliamentary democracy in Australia. It was in May 1909 that the Protectionist and Anti-Socialist parties joined forces to create the Commonwealth Liberal Party and form a united opposition against the Australian Labor Party (ALP) Government at the federal level.1 Most states had seen the creation of Liberal and Labor parties by 1910. Following the 1910 federal election the number of parties represented in the House * Dr Mark Rodrigues (Senior Researcher) and Dr Scott Brenton (2009 Australian Parliamentary Fellow), Politics and Public Administration Section, Australian Parliamentary Library. -

The Ministry of Public Input

The Ministry of Public Input: Report and Recommendations for Practice By Associate Professor Jennifer Lees-Marshment The University of Auckland, New Zealand August 2014 www.lees-marshment.org [email protected] Executive Summary Political leadership is undergoing a profound evolution that changes the role that politicians and the public play in decision making in democracy. Rather than simply waiting for voters to exercise their judgement in elections, political elites now use an increasingly varied range of public input mechanisms including consultation, deliberation, informal meetings, travels out in the field, visits to the frontline and market research to obtain feedback before and after they are elected. Whilst politicians have always solicited public opinion in one form or another, the nature, scale, and purpose of mechanisms that seek citizen involvement in policy making are becoming more diversified and extensive. Government ministers collect different forms of public input at all levels of government, across departments and through their own offices at all stages of the policy process. This expansion and diversification of public input informs and influences our leaders’ decisions, and thus has the potential to strengthen citizen voices within the political system, improve policy outcomes and enhance democracy. However current practice wastes both resources and the hope that public input can enrich democracy. If all the individual public input activities government currently engages in were collated and added up it would demonstrate that a vast amount of money and resources is already spent seeking views from outside government. But it often goes unseen, is uncoordinated, dispersed and unchecked. We need to find a way to ensure this money is spent much more effectively within the realities of government and leadership. -

List of Senators

The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia House of Representatives List of Members 46th Parliament Volume 19.1 – 20 September 2021 No. Name Electorate & Party Electorate office details & email address Parliament House State/Territory telephone & fax 1. Albanese, The Hon Anthony Norman Grayndler, ALP Email: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4022 Leader of the Opposition NSW 334A Marrickville Road, Fax: (02) 6277 8562 Marrickville NSW 2204 (PO Box 5100, Marrickville NSW 2204) Tel: (02) 9564 3588, Fax: (02) 9564 1734 2. Alexander, Mr John Gilbert OAM Bennelong, LP Email: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4804 NSW 32 Beecroft Road, Epping NSW 2121 Fax: (02) 6277 8581 (PO Box 872, Epping NSW 2121) Tel: (02) 9869 4288, Fax: (02) 9869 4833 3. Allen, Dr Katrina Jane (Katie) Higgins, LP Email: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4100 VIC 1/1343 Malvern Road, Malvern VIC 3144 Fax: (02) 6277 8408 Tel: (03) 9822 4422 4. Aly, Dr Anne Cowan, ALP Email: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4876 WA Shop 3, Kingsway Shopping Centre, Fax: (02) 6277 8526 168 Wanneroo Road, Madeley WA 6065 (PO Box 219, Kingsway WA 6065) Tel: (08) 9409 4517 5. Andrews, The Hon Karen Lesley McPherson, LNP Email: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 7860 Minister for Home Affairs QLD Ground Floor The Point 47 Watts Drive, Varsity Lakes QLD 4227 (PO Box 409, Varsity Lakes QLD 4227) Tel: (07) 5580 9111, Fax: (07) 5580 9700 6. Andrews, The Hon Kevin James Menzies, LP Email: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4023 VIC 1st Floor 651-653 Doncaster Road, Fax: (02) 6277 4074 Doncaster VIC 3108 (PO Box 124, Doncaster VIC 3108) Tel: (03) 9848 9900, Fax: (03) 9848 2741 7. -

Stubbornly Opposed: Influence of Personal Ideology in Politician's

Stubbornly Opposed: Influence of personal ideology in politician's speeches on Same Sex Marriage Preliminary and incomplete 2020-09-17 Current Version: http://eamonmcginn.com/papers/Same_Sex_Marriage.pdf. By Eamon McGinn∗ There is an emerging consensus in the empirical literature that politicians' personal ideology play an important role in determin- ing their voting behavior (called `partial convergence'). This is in contrast to Downs' theory of political behavior which suggests con- vergence on the position of the median voter. In this paper I extend recent empirical findings on partial convergence by applying a text- as-data approach to analyse politicians' speech behavior. I analyse the debate in parliament following a recent politically charged mo- ment in Australia | a national vote on same sex marriage (SSM). I use a LASSO model to estimate the degree of support or opposi- tion to SSM in parliamentary speeches. I then measure how speech changed following the SSM vote. I find that Opposers of SSM be- came stronger in their opposition once the results of the SSM na- tional survey were released, regardless of how their electorate voted. The average Opposer increased their opposition by 0.15-0.2 on a scale of 0-1. No consistent and statistically significant change is seen in the behavior of Supporters of SSM. This result indicates that personal ideology played a more significant role in determining changes in speech than did the position of the electorate. JEL: C55, D72, D78, J12, H11 Keywords: same sex marriage, marriage equality, voting, political behavior, polarization, text-as-data ∗ McGinn: Univeristy of Technology Sydney, UTS Business School PO Box 123, Broadway, NSW 2007, Australia, [email protected]). -

Representations . Rationales . Power

A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment for the award of the degree of: Bachelor of Arts (Honours) Science, Technology and Society Program University of Wollongong REPRESENTATIONS . RATIONALES . POWER STOCKLAND TRUST GROUP’S PUBLIC RELATIONS CAMPAIGN AND THE BATTLE OVER KURADJI SANDON POINT Colin Salter October 2003 Cover photo’s (from left to right): Sacred Fire, McCauleys Beach, 2002 Uncle Guboo & Friends at the Sandon Point Aboriginal Tent Embassy, 2001 Sandon Point Community picket, 2001 Outside NSW state parliament, Macquarie Street Sydney, 20 March 2002 The Valentine’s Day Blockade, 14 February 2002 Photo’s not specifically credited were supplied by members of the local community. AUTHORS CERTIFICATION I, Colin Salter, declare that this thesis, submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Bachelor of Arts (Honours) in the Science, Technology and Society Program, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Colin Salter 8 October 2003 They will justify their actions in the name of 'development'... development? What the first peoples of the [world] need is 'recovery', not development. Recovery from the very same colonization, domination and genocide that multinational corporations want to perpetuate for their own gains today. Leonard Peltier. i REPRESENTATIONS . RATIONALES . POWER ii abstract The future of an area known as Kuradji Sandon Point, located 70km south of Sydney, is currently under dispute. The area is of immense significance to Indigenous people, indicated by its use as a burial ground, campsite and meeting place stretching back to the dreamtime. -

List of Members Forty Fifth Parliament Volume 24 - 14 December 2016

The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia House of Representatives List of Members Forty Fifth Parliament Volume 24 - 14 December 2016 Name Electorate & Party Electorate office address, telephone and facsimile Parliament House State / Territory numbers & other office details where applicable telephone & facsimile numbers Abbott, The Hon Anthony John Warringah, LP Level 2, 17 Sydney Road (PO Box 450), Manly Tel: (02) 6277 4722 (Tony) NSW NSW 2095 Fax: (02) 6277 8403 Tel : (02) 9977 6411, Fax : (02) 9977 8715 E-mail: [email protected] Albanese, The Hon Anthony Grayndler, ALP 334A Marrickville Road, Marrickville NSW 2204 Tel: (02) 6277 4664 Norman NSW Tel : (02) 9564 3588, Fax : (02) 9564 1734 Fax: (02) 6277 8532 E-mail: [email protected] Alexander, Mr John Gilbert Bennelong, LP Suite 1, 44 - 46 Oxford St (PO Box 872), Epping Tel: (02) 6277 4804 OAM NSW NSW 2121 Fax: (02) 6277 8581 Tel : (02) 9869 4288, Fax : (02) 9869 4833 E-mail: [email protected] Aly, Dr Anne Cowan, ALP Shop 3, Kingsway Shopping Centre (PO Box 219, Tel: (02) 6277 4876 WA Kingsway), 168 Wanneroo Road, Madeley WA 6065 Fax: (02) 6277 8526 Tel : (08) 9409 4517, Fax : (08) 9409 9361 E-mail: [email protected] Andrews, The Hon Karen Lesley McPherson, LP Ground Floor The Point 47 Watts Drive (PO Box 409), Tel: (02) 6277 4360 Assistant Minister for Vocational QLD Varsity Lakes Qld 4227 Fax: (02) 6277 8462 Education and Skills Tel : (07) 5580 9111, Fax : (07) 5580 9700 E-mail: [email protected] Andrews, The Hon Kevin James Menzies, -

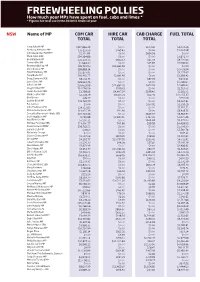

Freewheeling Pollies How Much Your Mps Have Spent on Fuel, Cabs and Limos * * Figures for Total Use in the 2010/11 Financial Year

FREEWHEELING POLLIES How much your MPs have spent on fuel, cabs and limos * * Figures for total use in the 2010/11 financial year NSW Name of MP COM CAR HIRE CAR CAB CHARGE FUEL TOTAL TOTAL TOTAL TOTAL Tony Abbott MP $217,866.39 $0.00 $103.42 $4,559.36 Anthony Albanese MP $35,123.59 $265.43 $0.00 $1,394.98 John Alexander OAM MP $2,110.84 $0.00 $694.56 $0.00 Mark Arbib SEN $34,164.86 $0.00 $0.00 $2,806.77 Bob Baldwin MP $23,132.73 $942.53 $65.59 $9,731.63 Sharon Bird MP $1,964.30 $0.00 $25.83 $3,596.90 Bronwyn Bishop MP $26,723.90 $33,665.56 $0.00 $0.00 Chris Bowen MP $38,883.14 $0.00 $0.00 $2,059.94 David Bradbury MP $15,877.95 $0.00 $0.00 $4,275.67 Tony Burke MP $40,360.77 $2,691.97 $0.00 $2,358.42 Doug Cameron SEN $8,014.75 $0.00 $87.29 $404.41 Jason Clare MP $28,324.76 $0.00 $0.00 $1,298.60 John Cobb MP $26,629.98 $11,887.29 $674.93 $4,682.20 Greg Combet MP $14,596.56 $749.41 $0.00 $1,519.02 Helen Coonan SEN $1,798.96 $4,407.54 $199.40 $1,182.71 Mark Coulton MP $2,358.79 $8,175.71 $62.06 $12,255.37 Bob Debus $49.77 $0.00 $0.00 $550.09 Justine Elliot MP $21,762.79 $0.00 $0.00 $4,207.81 Pat Farmer $0.00 $0.00 $177.91 $1,258.29 John Faulkner SEN $14,717.83 $0.00 $0.00 $2,350.51 Mr Laurie Ferguson MP $14,055.39 $90.91 $0.00 $3,419.75 Concetta Fierravanti-Wells SEN $20,722.46 $0.00 $649.97 $3,912.97 Joel Fitzgibbon MP 9,792.88 $7,847.45 $367.41 $2,675.46 Paul Fletcher MP $7,590.31 $0.00 $464.68 $2,475.50 Michael Forshaw SEN $13,490.77 $95.86 $98.99 $4,428.99 Peter Garrett AM MP $39,762.55 $0.00 $0.00 $1,009.30 Joanna Gash MP $78.60 $0.00