Stubbornly Opposed: Influence of Personal Ideology in Politician's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Procedural Digest 24 25 26 27 28

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES August/ September 2020 M T W T F Procedural Digest 24 25 26 27 28 No. 12 31 1 2 3 4 46th Parliament 24 August – 3 September 2020 Selected entries contain links to video footage via Parlview. Please note that the first time you click a [Watch] link, you may need to refresh the page (ctrl+F5) for the correct starting point. Bills 12.01 Jobkeeper bill introduced and passed all stages in one sitting The Treasurer presented the Coronavirus Economic Response Package (Jobkeeper Payments) Amendment Bill 2020 on 26 August. In his second reading speech, the Treasurer thanked the opposition for its support in progressing the bill through the parliament quickly to provide certainty to Australian businesses and employees. Following his speech, the House gave leave for the debate to be made an order of the day for a later hour. During the day, 28 members contributed to the second reading debate. At the conclusion of the debate, a second reading amendment moved by the shadow Treasurer was negatived on division and the question ‘that the bill be read a second time’ was carried on the voices. Following a message from the Governor-General recommending appropriation, the bill proceeded to the consideration in detail stage and several opposition amendments were negatived on division. Consideration in detail concluded and, by leave, an assistant minister moved the third reading. The question ‘that the bill be read a third time’ was carried on the voices. The Speaker granted the Manager of Opposition Business indulgence a number of times over the sitting fortnight to place on the record the voting intentions of independent and minor party members unable to attend the sittings due to the pandemic. -

2017 EABC Business Delegation to Canberra Mission Report

2017 EABC Business Delegation to Canberra Parliament House, Canberra 24-25 October 2017 Mission Report Overview On Tuesday 24 and Wednesday 25 October 2017, a delegation of EABC Members visited Parliament House in Canberra to meet with members of the Federal Government and Opposition. The delegation provided opportunities for members to engage in direct dialogue on the broad economic and business agenda, as well as the preparations underway for launching negotiations for an Australia-EU FTA. Programme The delegation programme on Tuesday 24 October included roundtable discussions with the Hon Michael McCormack MP, Minister for Small Business and the Hon Darren Chester MP, Minister for Infrastructure and Transport; followed by a Cocktail Reception with Guests of Honour the Hon Barnaby Joyce MP, Deputy Prime Minister, Minister for Agriculture and Water Resources, Minister for Resources and Northern Australia; the Hon Keith Pitt MP, Assistant Minister for Trade, Tourism and Investment; the Hon Chris Bowen MP, Shadow Treasurer; and Senator the Hon Mathias Cormann, Minister for Finance and Deputy Leader of the Government in the Senate. The programme continued with a working dinner with ministerial guests including the Hon Kelly O’Dwyer MP, Minister for Revenue and Financial Services; the Hon Craig Laundy MP, Assistant Minister for Industry, Innovation and Science; and Justin Brown, Deputy Secretary, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. The programme on Wednesday 25 October included roundtable discussions with Tom Skladzien, Chief of Staff -

Chronology of Same-Sex Marriage Bills Introduced Into the Federal Parliament: a Quick Guide

RESEARCH PAPER SERIES, 2017–18 UPDATED 24 NOVEMBER 2017 Chronology of same-sex marriage bills introduced into the federal parliament: a quick guide Deirdre McKeown Politics and Public Administration Section On 15 November 2017, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) announced the results of the voluntary Australian Marriage Law Postal survey. The ABS reported that, of the 79.5 per cent of Australians who expressed a view on the question Should the law be changed to allow same-sex couples to marry?, ‘the majority indicated that the law should be changed to allow same-sex couples to marry, with 7,817,247 (61.6 per cent) responding Yes and 4,873,987 (38.4 per cent) responding No’. On the same day Senator Dean Smith (LIB, WA) introduced, on behalf of eight cross-party co-sponsors, a bill to amend the Marriage Act 1961 (Cth) so as to redefine marriage as ‘a union of two people’. This is the fifth marriage equality bill introduced in the current (45th) Parliament, while six bills were introduced into the previous (44th) Parliament. Since the 2004 amendment to the Marriage Act 1961 (Cth) which inserted the current definition of marriage, 23 bills dealing with marriage equality or the recognition of overseas same-sex marriages have been introduced into the federal Parliament. Four bills have come to a vote: three in the Senate (in 2010, 2012 and 2013), and one in the House of Representatives (in 2012). These bills were all defeated at the second reading stage; consequently no bill has been debated by the second chamber. -

A History of Misconduct: the Case for a Federal Icac

MISCONDUCT IN POLITICS A HISTORY OF MISCONDUCT: THE CASE FOR A FEDERAL ICAC INDEPENDENT JO URNALISTS MICH AEL WES T A ND CALLUM F OOTE, COMMISSIONED B Y G ETUP 1 MISCONDUCT IN POLITICS MISCONDUCT IN RESOURCES, WATER AND LAND MANAGEMENT Page 5 MISCONDUCT RELATED TO UNDISCLOSED CONFLICTS OF INTEREST Page 8 POTENTIAL MISCONDUCT IN LOBBYING MISCONDUCT ACTIVITIES RELATED TO Page 11 INAPPROPRIATE USE OF TRANSPORT Page 13 POLITICAL DONATION SCANDALS Page 14 FOREIGN INFLUENCE ON THE POLITICAL PROCESS Page 16 ALLEGEDLY FRAUDULENT PRACTICES Page 17 CURRENT CORRUPTION WATCHDOG PROPOSALS Page 20 2 MISCONDUCT IN POLITICS FOREWORD: Trust in government has never been so low. This crisis in public confidence is driven by the widespread perception that politics is corrupt and politicians and public servants have failed to be held accountable. This report identifies the political scandals of the and other misuse of public money involving last six years and the failure of our elected leaders government grants. At the direction of a minister, to properly investigate this misconduct. public money was targeted at voters in marginal electorates just before a Federal Election, In 1984, customs officers discovered a teddy bear potentially affecting the course of government in in the luggage of Federal Government minister Australia. Mick Young and his wife. It had not been declared on the Minister’s customs declaration. Young This cheating on an industrial scale reflects a stepped aside as a minister while an investigation political culture which is evolving dangerously. into the “Paddington Bear Affair” took place. The weapons of the state are deployed against journalists reporting on politics, and whistleblowers That was during the prime ministership of Bob in the public service - while at the same time we Hawke. -

Notice Paper

5047 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL NOTICE PAPER No. 64 THURSDAY 23 JUNE 2016 The House meets this day at 10.00 am Contents Business of the House—Notice of Motion .......................................................................................................... 5048 Private Members’ Business .................................................................................................................................. 5048 Items in the Order of Precedence .............................................................................................................. 5048 Items outside the Order of Precedence ..................................................................................................... 5051 Government Business—Order of the Day ........................................................................................................... 5133 Business for Future Consideration ....................................................................................................................... 5134 Contingent Notices of Motions............................................................................................................................. 5135 5048 Legislative Council Notice Paper No. 64—Thursday 23 June 2016 BUSINESS OF THE HOUSE—NOTICE OF MOTION 1. Mr Searle to move— That, under section 41 of the Interpretation Act 1987, this House disallows the Government Sector Employment Amendment (Transfers to Non-Government Sector) Regulation 2016, published on the NSW Legislation website on 17 June 2016. (Notice given -

Liberal Women: a Proud History

<insert section here> | 1 foreword The Liberal Party of Australia is the party of opportunity and choice for all Australians. From its inception in 1944, the Liberal Party has had a proud LIBERAL history of advancing opportunities for Australian women. It has done so from a strong philosophical tradition of respect for competence and WOMEN contribution, regardless of gender, religion or ethnicity. A PROUD HISTORY OF FIRSTS While other political parties have represented specific interests within the Australian community such as the trade union or environmental movements, the Liberal Party has always proudly demonstrated a broad and inclusive membership that has better understood the aspirations of contents all Australians and not least Australian women. The Liberal Party also has a long history of pre-selecting and Foreword by the Hon Kelly O’Dwyer MP ... 3 supporting women to serve in Parliament. Dame Enid Lyons, the first female member of the House of Representatives, a member of the Liberal Women: A Proud History ... 4 United Australia Party and then the Liberal Party, served Australia with exceptional competence during the Menzies years. She demonstrated The Early Liberal Movement ... 6 the passion, capability and drive that are characteristic of the strong The Liberal Party of Australia: Beginnings to 1996 ... 8 Liberal women who have helped shape our nation. Key Policy Achievements ... 10 As one of the many female Liberal parliamentarians, and one of the A Proud History of Firsts ... 11 thousands of female Liberal Party members across Australia, I am truly proud of our party’s history. I am proud to be a member of a party with a The Howard Years .. -

Barton Deakin Standing Brief: Coalition Government Ministry 27 August 2018

Barton Deakin Standing Brief: Coalition Government Ministry 27 August 2018 TITLE MINISTER Prime Minister The Hon Scott Morrison MP Minister for Indigenous Affairs Senator the Hon Nigel Scullion Assistant Minister to the Prime Minister Mr Steve Irons MP Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Infrastructure, Transport and The Hon Michael McCormack Regional Development Minister for Regional Services, Sport, Local Government and Senator the Hon Bridget McKenzie Decentralisation Minister for Cities, Urban Infrastructure and Population The Hon Alan Tudge MP Assistant Minister to the Deputy Prime Minister Mr Andrew Broad MP Assistant Minister for Regional Development and Territories The Hon Sussan Ley MP Assistant Minister for Roads and Transport Mr Scott Buchholz MP Treasurer The Hon Josh Frydenberg MP Assistant Treasurer The Hon Stuart Robert MP Assistant Minister for Treasury and Finance Senator the Hon Zed Seselja Minister for Finance and the Public Service Senator the Hon Mathias Cormann (Vice-President of the Executive Council) (Leader of the Government in the Senate) Special Minister of State The Hon Alex Hawke MP Minister for Defence The Hon Christopher Pyne MP (Leader of the House) Minister for Defence Industry The Hon Steven Ciobo MP Minister for Veterans Affairs The Hon Darren Chester MP Minister for Defence Personnel The Hon Darren Chester MP (Deputy Leader of the House) Minister Assisting the Prime Minister for the Centenary of ANAC The Hon Darren Chester MP Assistant Minister for Defence Senator David Fawcett Minister for Foreign -

KJA Action Items Template

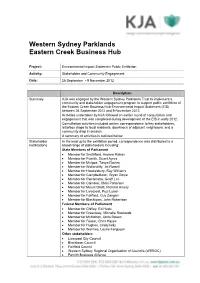

Western Sydney Parklands Eastern Creek Business Hub Project: Environmental Impact Statement Public Exhibition Activity: Stakeholder and Community Engagement Date: 26 September - 9 November 2012 Description Summary KJA was engaged by the Western Sydney Parklands Trust to implement a community and stakeholder engagement program to support public exhibition of the Eastern Creek Business Hub Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) between 26 September 2012 and 9 November 2012. Activities undertaken by KJA followed an earlier round of consultation and engagement that was completed during development of the EIS in early 2012. Consultation activities included written correspondence to key stakeholders, letterbox drops to local residents, doorknock of adjacent neighbours, and a community drop in session. A summary of activities is outlined below. Stakeholder In the lead up to the exhibition period, correspondence was distributed to a notifications broad range of stakeholders including: State Members of Parliament Member for Smithfield, Andrew Rohan Member for Penrith, Stuart Ayres Member for Mulgoa, Tanya Davies Member for Wollondilly, Jai Rowell Member for Hawkesbury, Ray Williams Member for Campbelltown, Bryan Doyle Member for Parramatta, Geoff Lee Member for Camden, Chris Patterson Member for Mount Druitt, Richard Amery Member for Liverpool, Paul Lynch Member for Fairfield, Guy Zangari Member for Blacktown, John Robertson Federal Members of Parliament Member for Chifley, Ed Husic Member for Greenway, Michelle Rowlands Member for -

Declan Clausen [email protected] I Was

Declan Clausen [email protected] I was privileged to have recently attended the 13th annual Science Meets Parliament conference (SmP) held in Canberra as the recipient of a generous APESMA Scholarship. SmP is organised by scientific lobby group Science and Technology Australia, brings together more than 150 of Australia’s preeminent industrial and research scientists and engineers. The goal of SmP is to allow participants to discuss science with other scientists, the media, influential public servants and parliamentarians. I currently study Environmental Engineering full time at the University of Newcastle, and work part time at the Hunter Water Corporation as an Industry Scholar. Outside of University and work, I am incredibly passionate about politics and policy creation, making SmP a near perfect match for my current skills, qualifications and interest. The first day of SmP began with members of the delegation working in small groups to put together a web outlining the influences on science, politics and public policy. The remainder of the first day was spent discussing these contributing influences including discussions with a media panel, a budget officer from the Commonwealth Treasury, the Deputy Secretary of the Department of Innovation, and with a team from the Centre for Public Awareness who specialise in social media and demonstrated how the new media influences science. These activities provided a detailed insight which would provide participants with knowledge that would set the scene for the rest of the conference. The first day of SmP ended in a spectacular fashion with a formal dinner held in the Great Hall of Parliament House. -

Dirty Power: Burnt Country 1 Greenpeace Australia Pacific Greenpeace Australia Pacific

How the fossil fuel industry, News Corp, and the Federal Government hijacked the Black Summer bushfires to prevent action on climate change Dirty Power: Burnt Country 1 Greenpeace Australia Pacific Greenpeace Australia Pacific Lead author Louis Brailsford Contributing authors Nikola Čašule Zachary Boren Tynan Hewes Edoardo Riario Sforza Design Olivia Louella Authorised by Kate Smolski, Greenpeace Australia Pacific, Sydney May 2020 www.greenpeace.org.au TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive summary 4 1. Introduction 6 2. The Black Summer bushfires 7 3. Deny, minimise, adapt: The response of the Morrison Government 9 Denial 9 Minimisation 10 Adaptation and resilience 11 4. Why disinformation benefits the fossil fuel industry 12 Business as usual 13 Protecting the coal industry 14 5. The influence of the fossil fuel lobby on government 16 6. Political donations and financial influence 19 7. News Corp’s disinformation campaign 21 News Corp and climate denialism 21 News Corp, the Federal Government and the fossil fuel industry 27 8. #ArsonEmergency: social media disinformation and the role of News Corp and the Federal Government 29 The facts 29 #ArsonEmergency 30 Explaining the persistence of #ArsonEmergency 33 Timeline: #ArsonEmergency, News Corp and the Federal Government 36 9. Case study – “He’s been brainwashed”: Attacking the experts 39 10. Case study – Matt Kean, the Liberal party minister who stepped out of line 41 11. Conclusions 44 End Notes 45 References 51 Dirty Power: Burnt Country 3 Greenpeace Australia Pacific EXECUTIVE SUMMARY stronger action to phase out fossil fuels, was aided by Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp media empire, and a Australia’s 2019/20 Black coordinated campaign of social media disinformation. -

Evobzq5zilluk8q2nary.Pdf

NOVEMBER 10 (GMT) – NOVEMBER 11 (AEST), 2020 YOUR DAILY TOP 12 STORIES FROM FRANK NEWS FULL STORIES START ON PAGE 3 NORTH AMERICA UK AUSTRALIA Trump blocks co-operation Optimism over vaccine rollout MP quits Labor frontbench The Trump administration threw the A coronavirus vaccine could start being Labor right faction warrior Joel Fitzgibbon presidential transition into tumult, distributed by Christmas after a jab has urged his party to make a major with President Donald Trump blocking developed by pharmaceutical giant shift on the environment and blue-collar government officials from co-operating Pfizer cleared a “significant hurdle”. voters after quitting shadow cabinet. with President-elect Joe Biden’s team Prime Minister Boris Johnson said initial Western Sydney MP Ed Husic replaced and Attorney General William Barr results suggested the vaccine was 90 per Fitzgibbon as the opposition’s resources authorizing the Justice Department to cent effective at protecting people from and agriculture spokesman after the probe unsubstantiated allegations of COVID-19 but warned these were “very, stunning resignation. Fitzgibbon has voter fraud. Some Republicans, including very early days”. been increasingly outspoken in a bruising Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, battle over energy policy with senior rallied behind Trump’s efforts to fight the figures from Labor’s left flank. election results. NORTH AMERICA UK NEW ZEALAND Election probes given OK Redundancies hit record high Napier braces for heavy rain Attorney General William Barr has More people were made redundant Flood-hit Napier residents remain on authorized federal prosecutors across between July and September than at any alert as more heavy rain is falling on the US to pursue “substantial allegations” point on record, according to new official the city, with another day of rain still to of voting irregularities, if they exist, before statistics, as the pandemic laid waste come. -

Second Morrison Government Ministry 29 June 2021 Overview

Barton Deakin Brief: Second Morrison Government Ministry 29 June 2021 Overview Prime Minister Scott Morrison MP has announced his new Cabinet and Ministry following the change in The Nationals leadership. Cabinet Changes - Barnaby Joyce MP is the new Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Development. Michael McCormack MP has been removed from the Cabinet and is now on the backbench. - David Littleproud MP retains his position as the Minster for Agriculture and is now also the Minister for Northern Australia. The role of Minister for Drought and Emergency Management will be given to Senator Bridget McKenzie. - Senator McKenzie will be returned to the Cabinet and is also the new Minister for Regionalisation, Regional Communications and Regional Education. - Keith Pitt MP, the Minister for Resources and Water will move to the outer Ministry, with his Northern Australia portfolio goes to David Littleproud MP. - Andrew Gee MP has been promoted to the Cabinet as the Minister for Defence Industry and Minister for Veterans’ Affairs. - Darren Chester MP, the former Minister for Veterans Affairs and Defence Personnel has been removed from the Cabinet and the Ministry. Ministry Changes - Mark Coulton MP, formerly the Minister for Regional Health, Regional Communications and Local Government is no longer a Minister. - Dr David Gillespie MP has become the Minister for Regional Health. For more information - The Ministry List from the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet For more information, contact David Alexander on +61 457 400 524, Grahame Morris on +61 411 222 680, Cheryl Cartwright on +61 419 996 066 or Jack de Hennin on +61 424 828 127.