Jeremy Corbyn's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Global Go to Think Tank Index Report

LEADING RESEARCH ON THE GLOBAL ECONOMY The Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) is an independent nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization dedicated to strengthening prosperity and human welfare in the global economy through expert analysis and practical policy solutions. Led since 2013 by President Adam S. Posen, the Institute anticipates emerging issues and provides rigorous, evidence-based policy recommendations with a team of the world’s leading applied economic researchers. It creates freely available content in a variety of accessible formats to inform and shape public debate, reaching an audience that includes government officials and legislators, business and NGO leaders, international and research organizations, universities, and the media. The Institute was established in 1981 as the Institute for International Economics, with Peter G. Peterson as its founding chairman, and has since risen to become an unequalled, trusted resource on the global economy and convener of leaders from around the world. At its 25th anniversary in 2006, the Institute was renamed the Peter G. Peterson Institute for International Economics. The Institute today pursues a broad and distinctive agenda, as it seeks to address growing threats to living standards, rules-based commerce, and peaceful economic integration. COMMITMENT TO TRANSPARENCY The Peterson Institute’s annual budget of $13 million is funded by donations and grants from corporations, individuals, private foundations, and public institutions, as well as income on the Institute’s endowment. Over 90% of its income is unrestricted in topic, allowing independent objective research. The Institute discloses annually all sources of funding, and donors do not influence the conclusions of or policy implications drawn from Institute research. -

Download PDF on Watching the Watchmen

REPORT Watching the Watchmen The Growing Case for Recall Elections and Increased Accountability for MPs Sam Goodman About the Author Sam Goodman is the author of the Imperial Premiership: The Role of the Modern Prime Minister in Foreign Policy Making, 1964-2015 (Manchester University Press: 2015). He is currently working as a political adviser to Peter Dowd MP the current Shadow Chief Secretary to the Treasury and has previously worked for a variety of Labour Members of Parliament including: Julie Cooper MP, Sir Mark Hendrick MP, Michael Dugher MP, and Rt. Hon Jack Straw MP. Watching the Watchmen: The Growing Case for Recall Elections and Increased Accountability for MPs Members of the House of Commons have long flirted parliamentary conventions and much procedure with the idea of British exceptionalism—citing the is arcane, which makes it difficult even for the UK’s role as the ‘mother of all parliaments’, its most ardent politically engaged citizen to follow unwritten constitution, its unitary voting system, proceedings and debates in the House of Commons. and the principle of the sovereignty of Parliament This separation between the governors and over the people—as a bulwark against the instability governed is exacerbated further by the limited customarily found in other western democracies. avenues available to the public to hold those elected In modern times, this argument held water as to account, which is exemplified by recent political it delivered stable parliamentary majorities, scandals, including allegations of bullying and peaceful transfers of power between governments, sexual harassment in the House of Commons. At the and kept in check the ideological fringes of both time of writing this report, no MP has been forced major political parties. -

The Contribution of the Afro-Descendant Soldiers to the Independence of the Bolivarian Countries (1810-1826)

Revista de Relaciones Internacionales, Estrategia y Seguridad ISSN: 1909-3063 [email protected] Universidad Militar Nueva Granada Colombia Reales, Leonardo The contribution of the afro-descendant soldiers to the independence of the bolivarian countries (1810- 1826) Revista de Relaciones Internacionales, Estrategia y Seguridad, vol. 2, núm. 2, julio-diciembre, 2007 Universidad Militar Nueva Granada Bogotá, Colombia Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=92720203 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative REVISTA - Bogotá (Colombia) Vol. 2 No. 2 - Julio - Diciembre 11 rev.relac.int.estrateg.segur.2(2):11-31,2007 THE CONTRIBUTION OF THE AFRO-DESCENDANT SOLDIERS TO THE INDEPENDENCE OF THE BOLIVARIAN COUNTRIES (1810-1826) Leonardo Reales (Ph.D. Candidate - The New School University) ABSTRACT In the midst of the independence process of the Bolivarian nations, thousands of Afro-descendant soldiers were incorporated into the patriot armies, as the Spanish Crown had done once independence was declared. What made people of African descent support the republican cause? Was their contribution to the independence decisive? Did Afro-descendant women play a key role during that process? Why were the most important Afro-descendant military leaders executed by the Creole forces? What was the fate of those soldiers and their descendants at the end of the war? This paper intends to answer these controversial questions, while explaining the main characteristics of Recibido: 3 de septiembre 2007 Aceptado: 8 de octubre 2007 society throughout the five countries freed by the Bolivarian armies in the 1810s and 1820s. -

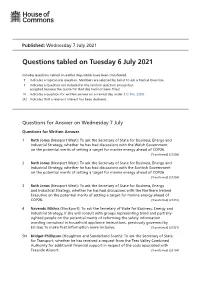

Questions Tabled on Tuesday 6 July 2021

Published: Wednesday 7 July 2021 Questions tabled on Tuesday 6 July 2021 Includes questions tabled on earlier days which have been transferred. T Indicates a topical oral question. Members are selected by ballot to ask a Topical Question. † Indicates a Question not included in the random selection process but accepted because the quota for that day had not been filled. N Indicates a question for written answer on a named day under S.O. No. 22(4). [R] Indicates that a relevant interest has been declared. Questions for Answer on Wednesday 7 July Questions for Written Answer 1 Ruth Jones (Newport West): To ask the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, whether he has had discussions with the Welsh Government on the potential merits of setting a target for marine energy ahead of COP26. [Transferred] (27308) 2 Ruth Jones (Newport West): To ask the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, whether he has had discussions with the Scottish Government on the potential merits of setting a target for marine energy ahead of COP26. [Transferred] (27309) 3 Ruth Jones (Newport West): To ask the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, whether he has had discussions with the Northern Ireland Executive on the potential merits of setting a target for marine energy ahead of COP26. [Transferred] (27310) 4 Navendu Mishra (Stockport): To ask the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, if she will consult with groups representing blind and partially- sighted people on the potential merits of reforming the safety information wording contained in household appliance instructions, previously governed by EU law, to make that information more inclusive. -

How Do British Political Parties Mobilise and Contact Voters To

How do British political parties mobilise and contact voters to increase turnout? Submitted by William Stephen King to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of MA by Research in Politics In August 2018 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: ………………………………………………………….. 1 Abstract This thesis will explore how British political parties over the period 2010-2017 have developed their mobilisation and contacting methods. Looking at social media, demographics, and other salient issues, I will construct a coherent and clear narrative of how British political parties have reacted to new technology, and what the advantages and disadvantages of doing so are. I shall be looking in particular at youth political mobilisation and contact, as this demographic has a poor election turnout record, so I shall explain why this is and how British political parties are attempting to contact and mobilise them (and how they have done so successfully). Looking at the 2010, 2015, and 2017 General Elections as well as the 2014 EU and 2016 referendums, this will enable me to take a look at Britain in different political times and differing levels of technology, from the first TV debates in 2010 to the first social media election in 2017. -

The Labour Party Is More Than the Shadow Cabinet, and Corbyn Must Learn to Engage with It

The Labour Party is more than the shadow cabinet, and Corbyn must learn to engage with it blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/the-labour-party-is-more-than-the-shadow-cabinet/ 1/11/2016 The three-day reshuffle of the shadow cabinet might have helped Jeremy Corbyn stamp his mark on the party but he needs to do more to ensure his leadership lasts, writes Eunice Goes. She explains the Labour leader must engage with all groups that have historically made up the party, while his rhetoric should focus more on policies that resonate with the public. Doing so will require a stronger vision of what he means by ‘new politics’ and, crucially, a better communications strategy. By Westminster standards Labour’s shadow cabinet reshuffle was ‘shambolic’ and had the key ingredients of a ‘pantomime’. At least, it was in those terms that it was described by a large number of Labour politicians and Westminster watchers. It certainly wasn’t slick, or edifying. Taking the best of a week to complete a modest shadow cabinet reshuffle was revealing of the limited authority the leader Jeremy Corbyn has over the Parliamentary Labour Party (PLP). Against the wishes of the Labour leader, the Shadow Foreign Secretary Hilary Benn and the Shadow Chief Whip Rosie Winterton kept their posts. However, Corbyn was able to assert his authority in other ways. He moved the pro-Trident Maria Eagle from Defence and appointed the anti-Trident Emily Thornberry to the post. He also imposed some ground rules on Hillary Benn and got rid of Michael Dugher and Pat McFadden on the grounds of disloyalty. -

1 CURRICULUM VITAE David Graham Blanchflower Department

CURRICULUM VITAE David Graham Blanchflower Department of Economics, Dartmouth College Hanover, New Hampshire, USA, 03755 Tel: (603) 632 1475; Cell: (603) 359-2077 Email: [email protected] Web page: www.dartmouth.edu/~blnchflr Date of birth: March 2nd, 1952. Nationality: Dual US and UK citizen. Children: Daniel John aged 27; Jennie age 32 and Kathryn age 34. Grand children: Lincoln James Denney (age 2); Angus Daniel Ross Davies (age 2); Hadley Davies; Isla Davies (age 1); Oliver Denny (age 9 months). Married: Carol Blanchflower Qualifications 1973 B.A. Soc. Sci. (Economics), University of Leicester, UK. 1975 Postgraduate Certificate in Education - (PGCE). Pass with distinction in teaching; Dudley College of Education, University of Birmingham, UK. 1981 M.Sc. (Econ), University of Wales, UK. 1985 Ph.D., University of London (Queen Mary College), UK. 1996 M.A. (Honorary), Dartmouth College. 1996 Honorary member of Phi Beta Kappa, Dartmouth chapter for ‘services to liberal scholarship’. 2007 Honorary Doctor of Letters (D.Litt.) for ‘services to economics’, University of Leicester, UK. 2009 Honorary Doctor of Science (D.Sc.), Queen Mary, University of London, July. 2011 Honorary Doctor of Letters (D.Litt.), University of Sussex, UK. 2014 Honorary Fellowship, Cardiff University, Wales, UK. Previous academic positions Northicote High School, Wolverhampton, UK, teacher, 1975-1976. Kilburn Polytechnic, London, UK, Lecturer, 1976-1977. Farnborough College of Technology, Hampshire, UK, Lecturer, 1977-1979. Institute for Employment Research, University of Warwick, UK, Research Officer, September 1984-July 1986. Department of Economics, University of Surrey, UK Assistant Professor (Lecturer), August 1986- August 1989. Associate Professor, Dartmouth College, 1989-1993. Department Chair, Department of Economics, Dartmouth College, July 1998 – June 2000. -

Ian Lavery Lab Vir- (Wansbeck) Tual T14 Chris Green Con Phys- (Bolton West) Ical 14 Monday 8 March 2021

Issued on: 8 March at 12.21pm Call lists for the Chamber Monday 8 March 2021 A list of Members, both virtually and physically pres- ent, selected to ask Oral Questions and to speak in response to Urgent Questions and Ministerial State- ments; and a list of Members both physically and virtually present selected to participate in substantive proceedings. Call lists are compiled and published incrementally as information becomes available. For the most up-to- date information see the parliament website: https:// commonsbusiness.parliament.uk/ CONTENTS 1. Oral Questions to the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions 3 2. Urgent Question: To ask the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care to make a statement on the Department of Health and Social Care’s recommendations on NHS staff pay 14 2 Monday 8 March 2021 3. Ministerial Statement: Minister of State for Patient Safety, Suicide Prevention and Mental Health on Women’s Health Strategy: Call for Evi- dence 18 4. Budget Debate: Third Day 20 Monday 8 March 2021 3 ORAL QUESTIONS TO THE SECRETARY OF STATE FOR WORK AND PENSIONS After Prayers Order Member Question Party Vir- Minister tual/ replying Phys- ical 1 + 2 Richard Fuller What assessment Con Phys- Secretary + 3 (North East she has made ical Coffey Bedfordshire) of the effect of the removal of the requirement that Kickstart applicants bid to deliver a mini- mum of 30 jobs on the accessibil- ity of that scheme to a wider range of employers. 2 Peter Gibson What assessment Con Vir- Secretary (Darlington) she has made tual Coffey of the effect of the removal of the requirement that Kickstart applicants bid to deliver a mini- mum of 30 jobs on the accessibil- ity of that scheme to a wider range of employers. -

Formal Minutes of the Committee

House of Commons Welsh Affairs Committee Formal Minutes of the Committee Session 2010-11 2 The Welsh Affairs Committee The Welsh Affairs Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Office of the Secretary of State for Wales (including relations with the National Assembly for Wales.) Current membership David T.C. Davies MP (Conservative, Monmouth) (Chair) Stuart Andrew MP (Conservative, Monmouth) Guto Bebb MP (Conservative, Pudsey) Alun Cairns MP (Conservative, Vale of Glamorgan), Geraint Davies MP (Labour, Swansea West) Jonathan Edwards, MP (Plaid Cymru, Carmarthen East and Dinefwr) Mrs Siân C. James MP (Labour, Swansea East) Susan Elan Jones MP (Labour, Clwyd South) Karen Lumley MP (Conservative, Redditch) Jessica Morden MP (Labour, Newport East) Owen Smith MP (Labour, Pontypridd) Mr Mark Williams, MP (Liberal Democrat, Ceredigion) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the internet via www.parliament.uk. Publications The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including press notices) are on the internet at www.parliament.uk/parliamentary_committees/welsh_affairs_committee.cfm Committee staff The current staff of the Committee is Adrian Jenner (Clerk), Anwen Rees (Inquiry Manager), Jenny Nelson (Senior Committee Assistant), Dabinder Rai (Committee Assistant), Mr Tes Stranger (Committee Support Assistant) and Laura Humble (Media Officer). Contacts All correspondence should be addressed to the Clerk of the Welsh Affairs Committee, House of Commons, 7 Millbank, London SW1P 3JA. -

Social Cleavages, Political Institutions and Party Systems: Putting Preferences Back Into the Fundamental Equation of Politics A

SOCIAL CLEAVAGES, POLITICAL INSTITUTIONS AND PARTY SYSTEMS: PUTTING PREFERENCES BACK INTO THE FUNDAMENTAL EQUATION OF POLITICS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE AND THE COMMITTEE ON GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Heather M. Stoll December 2004 c Copyright by Heather M. Stoll 2005 All Rights Reserved ii I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. David D. Laitin, Principal Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Beatriz Magaloni-Kerpel I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Morris P. Fiorina Approved for the University Committee on Graduate Studies. iii iv Abstract Do the fundamental conflicts in democracies vary? If so, how does this variance affect the party system? And what determines which conflicts are salient where and when? This dis- sertation explores these questions in an attempt to revitalize debate about the neglected (if not denigrated) part of the fundamental equation of politics: preferences. While the com- parative politics literature on political institutions such as electoral systems has exploded in the last two decades, the same cannot be said for the variable that has been called social cleavages, political cleavages, ideological dimensions, and—most generally—preferences. -

Research Note: Former Special Advisers in Cabinet, 1979-2013

Research Note: Former Special Advisers in Cabinet, 1979-2013 Executive Summary Sixteen special advisers have gone on to become Cabinet Ministers. This means that of the 492 special advisers listed in the Constitution Unit database in the period 1979-2010, only 3% entered Cabinet. Seven Conservative party Cabinet members were formerly special advisers. o Four Conservative special advisers went on to become Cabinet Ministers in the 1979-1997 period of Conservative governments. o Three former Conservative special advisers currently sit in the Coalition Cabinet: David Cameron, George Osborne and Jonathan Hill. Eight Labour Cabinet members between 1997-2010 were former special advisers. o Five of the eight former special advisers brought into the Labour Cabinet between 1997-2010 had been special advisers to Tony Blair or Gordon Brown. o Jack Straw entered Cabinet in 1997 having been a special adviser before 1979. One Liberal Democrat Cabinet member, Vince Cable, was previously a special adviser to a Labour minister. The Coalition Cabinet of January 2013 currently has four members who were once special advisers. o Also attending Cabinet meetings is another former special adviser: Oliver Letwin as Minister of State for Policy. There are traditionally 21 or 22 Ministers who sit in Cabinet. Unsurprisingly, the number and proportion of Cabinet Ministers who were previously special advisers generally increases the longer governments go on. The number of Cabinet Ministers who were formerly special advisers was greatest at the end of the Labour administration (1997-2010) when seven of the Cabinet Ministers were former special advisers. The proportion of Cabinet made up of former special advisers was greatest in Gordon Brown’s Cabinet when almost one-third (30.5%) of the Cabinet were former special advisers. -

Disposal Services Agency Annual Report and Accounts 2006-2007

Annual Report & Accounts 2006-2007 DisposalSMART 1 What is the Disposal Services Agency? The Disposal Services Agency (DSA) is the sole authority for the disposal process of all surplus defence equipment, with the exception of nuclear, land and buildings. The Agency targets potential markets particularly in developing countries in a pro-active manner; to enable them to procure formally used British defence equipment instead of equipment from other countries. The principal activity of the Agency is the provision of disposal and sales services to MoD and other parts of the public sector. These services include Government-to-Government Sales, Asset Realisation, Inventory Disposals, Site Clearances, Repayment Sales, Waste Management and Consultancy and Valuation Services. DSA’s Aim: To secure the best nancial return from the sale of surplus equipment and stores; to minimise the cost of sales and to operate as an intelligent contracting organisation with various agreements with British Industry and Commerce. DSA’s Mission: To provide Defence and other users with an agreed, effective and ef cient disposals and sales service in order to support UK Defence capability. DSA’s Vision: To be the best government Disposals organisation in the world. DisposalSMART Annual Report & Accounts 2006-2007 A Defence Agency of the Ministry of Defence Annual Report and Accounts 2006-2007 Presented to the House of Commons pursuant to section 7 of the Government Resources and Accounts Act 2000 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 23rd July 2007 HC 705