The Carp River Bloomery Iron Forge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property

NFS Form 10-900-b 0MB No. 1024-0018 (Jan. 1987) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multipler Propertyr ' Documentation Form NATIONAL This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing ____Iron and Steel Resources of Pennsylvania, 1716-1945_______________ B. Associated Historic Contexts_____________________________ ~ ___Pennsylvania Iron and Steel Industry. 1716-1945_________________ C. Geographical Data Commonwealth of Pennsylvania continuation sheet D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, J hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requiremerytS\set forth iri36JCFR PafrfsBOfcyid the Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Planning and Evaluation. Signature of certifying official Date / Brent D. Glass Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission State or Federal agency and bureau I, hereby, certify that this multiple -

An Analysis of the Metal Finds from the Ninth-Century Metalworking

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-2017 An Analysis of the Metal Finds from the Ninth-Century Metalworking Site at Bamburgh Castle in the Context of Ferrous and Non-Ferrous Metalworking in Middle- and Late-Saxon England Julie Polcrack Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Medieval History Commons Recommended Citation Polcrack, Julie, "An Analysis of the Metal Finds from the Ninth-Century Metalworking Site at Bamburgh Castle in the Context of Ferrous and Non-Ferrous Metalworking in Middle- and Late-Saxon England" (2017). Master's Theses. 1510. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/1510 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN ANALYSIS OF THE METAL FINDS FROM THE NINTH-CENTURY METALWORKING SITE AT BAMBURGH CASTLE IN THE CONTEXT OF FERROUS AND NON-FERROUS METALWORKING IN MIDDLE- AND LATE-SAXON ENGLAND by Julie Polcrack A thesis submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The Medieval Institute Western Michigan University August 2017 Thesis Committee: Jana Schulman, Ph.D., Chair Robert Berkhofer, Ph.D. Graeme Young, B.Sc. AN ANALYSIS OF THE METAL FINDS FROM THE NINTH-CENTURY METALWORKING SITE AT BAMBURGH CASTLE IN THE CONTEXT OF FERROUS AND NON-FERROUS METALWORKING IN MIDDLE- AND LATE-SAXON ENGLAND Julie Polcrack, M.A. -

Iron Production in Iceland

Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Fornleifafræði Iron Production in Iceland A reexamination of old sources Ritgerð til B.A. prófs í fornelifafræði Florencia Bugallo Dukelsky Kt.: 0102934489 Leiðbeinandi: Orri Vésteinsson Abstract There is good evidence for iron smelting and production in medieval Iceland. However the nature and scale of this prodction and the reasons for its demise are poorly understood. The objective of this essay is to analyse and review already existing evidence for iron production and iron working sites in Iceland, and to assses how the available data can answer questions regarding iron production in the Viking and medieval times Útdráttur Góðar heimildir eru um rauðablástur og framleiðslu járns á Íslandi á miðöldum. Mikið skortir hins vegar upp á skilning á skipulagi og umfangi þessarar framleiðslu og skiptar skoðanir eru um hvers vegna hún leið undir lok. Markmið þessarar ritgerðar er að draga saman og greina fyrirliggjandi heimildir um rauðablástursstaði á Íslandi og leggja mat á hvernig þær heimildir geta varpað ljósi á álitamál um járnframleiðslu á víkingaöld og miðöldum. 2 Table of Contents Háskóli Íslands ............................................................................................................. 1 Hugvísindasvið ............................................................................................................. 1 Ritgerð til B.A. prófs í fornelifafræði ........................................................................ 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................... -

Bloomery Design

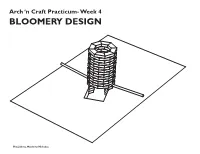

Arch ‘n Craft Practicum- Week 4 BLOOMERY DESIGN Hiu, Julieta, Matthew, Nicholas 7 3/4" The Stack: 3 3/4" In our ideal model we would use refractory bricks, either rectangular bricks or curved bricks which would help us make a circular 1'-8" stack. The stack would be around 3 feet tall with a 1 foot diameter for the inner wall of the stack. There will be openings about 3 brick lengths up(6-9 inches) from the ground on 1'-0" opposite ends of the stack. Attached to these openings will be our tuyeres which in turn will connect to our air sources. Building a circular stack would be beneficial to the type of air distribution we want to create within our furnace; using two angled tuyeres we would like air to move clockwise and counterclock- Bloomery Plan wise. We would like to line the inside of the stack with clay to provide further insulation. Refractory bricks would be an ideal material to use because the minerals they are com- posed of do not change chemically when 1'-0" exposed to high heat, some examples of these materials are aluminum, manganese, silica and zirconium. Other comments: 3'-0" Although we have opted to use refractory bricks, which would be practical for our intended purpose, we briefly considered using Vycor glass which can withstand high tem- peratures of up to 900 degrees celsius or approximately 1652 degrees Fahrenheit, which Tuyere height: Pitched -10from horizontal 7" would be enough for our purposes. Bloomery Section Ore/ Charcoal: Our group has decided to use Magnetite ore along with charcoal for the smelt. -

The Early Medieval Cutting Edge Of

University of Bradford eThesis This thesis is hosted in Bradford Scholars – The University of Bradford Open Access repository. Visit the repository for full metadata or to contact the repository team © University of Bradford. This work is licenced for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence. The Early Medieval Cutting Edge of Technology: An archaeometallurgical, technological and social study of the manufacture and use of Anglo-Saxon and Viking iron knives, and their contribution to the early medieval iron economy Volume 1 Eleanor Susan BLAKELOCK BSc, MSc Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Division of Archaeological, Geographical and Environmental Sciences University of Bradford 2012 Abstract The Early Medieval Cutting Edge of Technology: An archaeometallurgical, technological and social study of the manufacture and use of Anglo-Saxon and Viking iron knives, and their contribution to the early medieval iron economy Eleanor Susan Blakelock A review of archaeometallurgical studies carried out in the 1980s and 1990s of early medieval (c. AD410-1100) iron knives revealed several patterns (Blakelock & McDonnell 2007). Clear differences in knife manufacturing techniques were present in rural cemeteries and later urban settlements. The main aim of this research is to investigate these patterns and to gain an overall understanding of the early medieval iron industry. This study has increased the number of knives analysed from a wide spectrum of sites across England, Scotland and Ireland. Knives were selected for analysis based on x-radiographs and contextual details. Sections were removed for more detailed archaeometallurgical analysis. The analysis revealed a clear change through time, with a standardisation in manufacturing techniques in the 7th century, and differences between the quality of urban and rural knives. -

Hopewell Village

IRONMAKING IN EARLY AMERICA the Revolutionary armies, is representative of (such as Valley Forge) to be made into the tougher the hundreds of ironmaking communities that and less brittle wrought iron. This was used to Hopewell In the early days of colonial America, iron tools supplied the iron needs of the growing nation. make tools, hardware, and horseshoes. and household items were brought over from Europe by the settlers or imported at a high cost. Until surpassed by more modern methods, cold- HOPEWELL FURNACE Village The colonists, early recognizing the need to manu blast charcoal-burning furnaces, such as that NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE • PENNSYLVANIA facture their own iron, set up a number of iron at Hopewell, supplied all the iron. These furnaces In an age when most businesses were operated by works, notably at Falling Creek, Va., and Saugus, consumed about 1 acre of trees a day for fuel, one or two men in a shop, Hopewell employed at Mass. Operations gradually spread throughout so they had to be located in rural areas close to least 65 men, with some responsible for two or the colonies, and by the end of the 1700's, south a timber supply. more jobs. As the nearest town was many miles eastern Pennsylvania had become the industry's away, the ironmaster built a store to supply his center. Hopewell Village, founded by Mark Bird Since the pig iron produced by these furnaces workers, many of whom lived in company-owned in 1770 in time to supply cannon and shot for had a limited use, much of it was sent to forges homes. -

Centre for Archaeology Guidelines

2001 01 Centre for Archaeology Guidelines Archaeometallurgy Archaeometallurgy is the study of metalworking structures, tools, waste products and finished metal artefacts, from the Bronze Age to the recent past. It can be used to identify and interpret metal working structures in the field and, during the post-excavation phases of a project, metal working waste products, such as slags, crucibles and moulds.The technologies used in the past can be reconstructed from the information obtained. Scientific techniques are often used by archaeometallurgists, as they can provide additional information. Archaeometallurgical investigations can provide evidence for both the nature and scale of mining, smelting, refining and metalworking trades, and aid understanding of other structural and artefactual evidence.They can be crucial in understanding the economy of a site, the nature of the occupation, the technological capabilities of its occupants and their cultural affinities. In order that such evidence is used to its fullest, it is essential that Figure 1 Experimental iron working at Plas Tan y Bwlch: archaeometallurgy is considered at each stage of archaeological projects, removing an un-consolidated bloom from a furnace. and from their outset. (Photograph by David Starley) These Guidelines aim to improve the its date and the nature of the occupation. For made use of stone tools or fire to weaken the retrieval of information about all aspects of example, archaeological evidence for mining rock (Craddock 1995, 31–7) and this can be metalworking from archaeological tin will only be observed in areas where tin distinguished from later working where iron investigations. They are written mainly for ores are found, iron working evidence is tools or explosives were used. -

What a Blast Furnace Is and How It Works

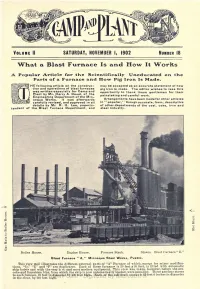

VOLUME II SATURDAY, NOVEMBER I, 1902 NUMBER 18 What a Blast Furnace Is and How It Works Popular Article for the Scientifically Uneducated on the Parts of a Furnace and How Pig Iron Is Made. 1 HE following article on the construc- may be accepted as an accurate statement of how tion and operations of blast furnaces pig iron is made. The editor wishes to take this was written especially for Camp and opportunity to thank these gentlemen for their Plant Mr. A of the by Harry Deuel, painstaking and careful work. Engineering Department of the Min- have articles nequa Works. It was afterwards Arrangements been madefor other carefully revised, and approved in all in "popular," though accurate, form, descriptive details by Mr R. H. Lee, superin- of other departments of the coal, coke, iron and tendent of the Blast Furnace Department, and steel industry. " Boiler House. Engine House. Furnace Stack. Stoves. Blast furnace B. Blast Furnace "A," Minnequa Steel Works, Pueblo. This view well illustrates the different external parts of "A" Furnace of which, except for minor modifica- tions, "D," "E" and "F" are duplicates Each of these furnaces is 20 feet x 95 feet, is fitted with automatic skip hoists and with the very b st and most modern equipment. This vi-w was taken, however, before the ore. coke and limestone bins, from which the skip is now automatically loaded, were installed. There are four stoves to each furnace. 21 feet in diameter by 106 feet high. Each of the tall draft stacks is 12 feet 6 inches in diameter in the clear, by 210 feet high. -

Using Cooled Mirror Hygrometers to Optimize Cold & Hot Blast Furnace

Application Note Using Cooled Mirror Hygrometers to optimize Cold & Hot Blast Furnace processes Application Background The purpose of a blast furnace is to chemically reduce and physically convert iron oxides into liquid iron. The blast furnace is a huge, steel stack lined with brick. Iron ore, coke and limestone are dumped into the top, and preheated “hot blast” air is blown into the bottom. The raw materials gradually descend to the bottom of the furnace where they become the final products of liquid slag and liquid iron. These liquid products are drained from the furnace at regular intervals. The hot air that was blown into the bottom of the furnace ascends to the top in 6 to 8 seconds after going through numerous chemical reactions. These hot gases exit the top of the blast furnace and proceed through gas cleaning equipment where Cold Blast, Hot blast & Stoves particulate matter is removed from the gas and the gas is cooled. This gas has a considerable energy value so it is burned as a fuel in the "hot blast stoves" which are used to preheat the air entering the blast furnace to become "hot blast". Any of the gas not burned in the stoves is sent to the boiler house and is used to generate steam which turns a turbo blower that generates the compressed air known as "cold blast" that comes to the stoves. Why is Moisture Critical? This process can be optimized by proper control of the flame temperature, which is in turn affected by the moisture content of the blast air. -

Refractory & Engineering

Refractory & Engineering Solutions for Hot Blast Stoves and Blast Furnace Linings Blast Furnace Technologies Refractory & Engineering The Company – The Program Paul Wurth Refractory & Engineering GmbH has been integrated into the Paul Wurth Group in ` Blast furnace linings for extended service life December 2004. This alliance offers, on a turnkey ` Blast furnace cooling systems basis, single source supply and procurement options for complete blast furnace plants. ` Turnkey hot blast stoves with internal or external combustion chamber Originally, Paul Wurth Refractory & Engineering ` Ceramic burners with ultra-low CO emission GmbH has been founded as DME in 1993 through the merger of departments of Didier-Werke AG ` Highly effective stress corrosion protection and Martin & Pagenstecher GmbH. Customers systems benefit from the unsurpassed experience and ` Complete hot blast main systems know-how that both companies have developed in the field of hot blast stove engineering, refractory ` Complete heat recovery systems lining design, and hot metal production. ` Refractory linings for smelting and direct reduction vessels Paul Wurth Refractory & Engineering GmbH is always striving for world class stove and refractory ` Refractory linings for coke dry quenching designs to meet demanding market requirements, ` Refractory linings for pellet plants such as larger production capacity, extended ser- vice life, optimized refractory selection, and high Highly experienced and motivated teams of engineers, energy efficiency. designers and project managers -

Blast Furnace Stove Dome and Hot Blast Main

BLAST FURNACE STOVE DOME AND HOT BLAST MAIN The quality and composition of iron produced in the blast furnace is directly related to the hearth temperature. This, in turn, is dependent on the temperature of the hot blast delivered from the blast furnace stoves. To maximise the efficiency of the stoves, they are operated at high temperatures, close to the safe working limit of the refractories. This makes it critical to carefully monitor the stove temperature. BLAST FURNACES AND STOVES Blast furnaces heat iron ore to a period of accumulation, flow is produce the iron required as a reversed, and the hot stove is used raw material for steel-making. For to preheat the incoming air. efficient operation, the air is heated Stoves are alternated, storing heat before being sent into the furnace. and dissipating heat on a regular This ‘hot blast’ technique – flow reversal plan. Many blast preheating air blown into the furnaces are serviced by three or blast furnace – dates back to the more stoves, so that while two are Industrial Revolution, and was being heated, the air blast can pass developed to permit higher through the regenerative chamber furnace temperatures, increasing of the third stove on its way to the the furnace capacity. furnace. Preheating the air intensifies and Accurate monitoring of the stove accelerates the burning of the temperature supports efficient coke. A blast furnace fed with operation – higher temperatures air preheated to between 900- are more efficient and, by reducing 1250oC (1652-2282oF) can generate coke consumption, are more cost- smelting temperatures of about effective. -

1Natalija Dolic.Qxd

Journal of Mining and Metallurgy, 38 (3‡4) B (2002) 123 - 141 STATE OF THE DIRECT REDUCTION AND REDUCTION SMELTING PROCESSES A.Markoti}*, N.Doli}* and V.Truji}** * Faculty of Metallurgy, Aleja narodnih heroja 3, 44 103 Sisak, Croatia ** Copper Institute, Bor, Yugoslavia (Received 5 October 2002; accepted 24 December 2002 ) Abstract For quite a long time efforts have been made to develop processes for producing iron i.e. steel without employing conventional procedures – from ore, coke, blast furnace, iron, electric arc furnace, converter to steel. The insufficient availability and the high price of the coking coals have forced many countries to research and adopt the non-coke-consuming reduction and metal manufacturing processes (non-coke metallurgy, direct reduction, direct processes). This paper represents a survey of the most relevant processes from this domain by the end of 2000, which display a constant increase in the modern process metallurgy. Keywords: iron, coal, direct reduction, reduction smelting, main processes, reduction. 1. Introduction The processes that produce iron by reduction of iron ore below the melting point of the iron produced are generally classified as direct reduction processes, and the product is referred to as direct reduced iron. The processes that produce molten metal, similar to blast furnace liquid metal, directly from ore are referred to as direct smelting processes. In some of the processes the objective is to produce liquid steel directly from ore and these processes are classified as direct steelmaking processes. J. Min. Met. 38 (3 ‡ 4) B (2002) 123 A. Markoti} et al. These broad categories are clearly distinguished by the characteristics of their respective products, although all of these products may be further treated to produce special grades of steel in the same steelmaking or refining process [1].