R.W. Justin Clark- Thesis- IUPUI- Combined Draft [2-4-2017]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PAUL KURTZ in MEMORIAM Paul Kurtz, Philosopher, Humanist Leader, and Founder of the Modern Skeptical Movement, Dies at Eighty-Six TOM FLYNN

Jan Feb 13 2_SI new design masters 11/29/12 11:26 AM Page 5 [ PAUL KURTZ IN MEMORIAM Paul Kurtz, Philosopher, Humanist Leader, and Founder of the Modern Skeptical Movement, Dies at Eighty-Six TOM FLYNN Paul Kurtz, founder and longtime chair At NYU Kurtz studied philosophy of the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry, under Sidney Hook, who had himself the Council for Secular Humanism, and been a protégé of the pragmatist philoso- the Center for Inquiry, died at the age pher John Dewey. The philosophy of of eighty-six on October 20, 2012. He Dewey and Hook, arguably the greatest was one of the most influential figures American thinkers in the humanist tra- in the humanist and skeptical move- dition, would deeply in fluence Kurtz’s ments from the late 1960s through the thought and activism. Kurtz graduated first decade of the twenty-first century. from NYU in 1948 and earned his PhD Among his best-known creations are in philosophy at Columbia University in the skeptics’ magazine SKEPTICAL IN- 1952. QUIRER, the secular humanist magazine Free Inquiry, and the independent pub- Academic Career lisher Prometheus Books. Kurtz taught philosophy at Trinity Col- Jonathan Kurtz, Paul’s son, told SI that lege from 1952 to 1959. He joined the his father had a “‘joyous’ last day, joking, faculty at Union College from 1961 to laughing, etc. He then died suddenly to- 1965; during this period he was also a ward bedtime. There was no suffering.” A visiting lecturer at the New School for joint CFI/CSI/CSH statement marked Social Research. -

Translation Ellehumanist Ur S

. ! se rv ic e e a m n p d a t p hy a r t i c i a p l a tr t i u o is n m ility um h – e t h ic a l d e v e l o p m e n t peace and ice l just cia so critical thinking responsibility s gl s ob e al awaren e n vironmental ism ، American Humanist Association: www.americanhumanist.org Humanist Manifesto: www.americanhumanist.org/what-is-humanism/manifesto3/ The Ten Commitments: www.humanistcommitments.org Effective Altruism: https://www.effectivealtruism.org Camp Quest: www.campquest.org Foundation Beyond Belief: https://foundationbeyondbelief.org Oasis: www.networkoasis.org Sunday Assembly: www.sundayassembly.com Unitarian Universalist Association: www.UUA.org Center For Inquiry: www.centerforinquiry.org Freedom From Religion Foundation: www.ffrf.org American Ethical Union: www.aeu.org Secular Student Alliance: www.secularstudents.org Skeptic Society: https://www.skeptic.com Black Non-Believers www.blacknonbelievers.com Hispanic American Freethinkers: http://hafree.org Freethought Society: www.ftsociety.org Friendly Atheist: www.friendlyatheist.patheos.com Thinking Atheist: www.thethinkingatheist.com American Atheists: www.atheists.org Annabelle & Aiden Book Series: www.annabelleandaiden.com Stardust Book Series: www.stardustscience.com Society for Humanistic Judaism: www.shj.org Openly Secular: www.openlysecular.org Secular Coalition: www.secular.org Teacher Institute for Evolutionary Science: www.tieseducation.org Richard Dawkins Foundation: www.richarddawkins.net Humanists International: www.humanists.international Humanist Community -

Humanism in America Today

Humanism Humanism in America Today Humanism in America Today Summary: Writers and public figures with large audiences have contributed to the increasing popularity of atheism and Humanism in the United States. Thousands of people attended the 2012 Reason Rally, demonstrating the rise of atheism as a political movement, yet many atheists and Humanists experience marginalization within American culture and the challenge of translating a mostly intellectual doctrine into a social movement. On a rainy day in March of 2012, roughly 20,000 people from all parts of the Humanist, atheist, and freethinking movements converged on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. They gathered to celebrate secular values, dispel stereotypes about secular people, and support secular equality. Sponsored by twenty of the country’s major secular organizations, the Reason Rally featured live music and remarks from academics, bloggers, student activists, media personalities, comedians, and two members of Congress, including Representative Pete Stark (D-CA), the first openly atheistic member of Congress. The Reason Rally is evidence of a growing energy and excitement among atheists in America. This new visibility of secularism was inspired in part by the “New Atheists”—including authors such as Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris and Christopher Hitchens—who have pushed the discussion of the potentially dangerous aspects of religion to the forefront of the public discussion. More people than ever are turning away from traditional religious faith, with the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life reporting that, as of 2014, some 20% of the US population identify as “unaffiliated.” This is particularly true of the rising millennial generation, which has increasingly come to view institutional and traditional religion as associated with conservative social views such as opposition to gay marriage, and is therefore much more skeptical of the role of religion in public life than their parents and grandparents. -

Markets Not Capitalism Explores the Gap Between Radically Freed Markets and the Capitalist-Controlled Markets That Prevail Today

individualist anarchism against bosses, inequality, corporate power, and structural poverty Edited by Gary Chartier & Charles W. Johnson Individualist anarchists believe in mutual exchange, not economic privilege. They believe in freed markets, not capitalism. They defend a distinctive response to the challenges of ending global capitalism and achieving social justice: eliminate the political privileges that prop up capitalists. Massive concentrations of wealth, rigid economic hierarchies, and unsustainable modes of production are not the results of the market form, but of markets deformed and rigged by a network of state-secured controls and privileges to the business class. Markets Not Capitalism explores the gap between radically freed markets and the capitalist-controlled markets that prevail today. It explains how liberating market exchange from state capitalist privilege can abolish structural poverty, help working people take control over the conditions of their labor, and redistribute wealth and social power. Featuring discussions of socialism, capitalism, markets, ownership, labor struggle, grassroots privatization, intellectual property, health care, racism, sexism, and environmental issues, this unique collection brings together classic essays by Cleyre, and such contemporary innovators as Kevin Carson and Roderick Long. It introduces an eye-opening approach to radical social thought, rooted equally in libertarian socialism and market anarchism. “We on the left need a good shake to get us thinking, and these arguments for market anarchism do the job in lively and thoughtful fashion.” – Alexander Cockburn, editor and publisher, Counterpunch “Anarchy is not chaos; nor is it violence. This rich and provocative gathering of essays by anarchists past and present imagines society unburdened by state, markets un-warped by capitalism. -

Anarchism and Religion

Anarchism and Religion Nicolas Walter 1991 For the present purpose, anarchism is defined as the political and social ideology which argues that human groups can and should exist without instituted authority, and especially as the historical anarchist movement of the past two hundred years; and religion is defined as the belief in the existence and significance of supernatural being(s), and especially as the prevailing Judaeo-Christian systemof the past two thousand years. My subject is the question: Is there a necessary connection between the two and, if so, what is it? The possible answers are as follows: there may be no connection, if beliefs about human society and the nature of the universe are quite independent; there may be a connection, if such beliefs are interdependent; and, if there is a connection, it may be either positive, if anarchism and religion reinforce each other, or negative, if anarchism and religion contradict each other. The general assumption is that there is a negative connection logical, because divine andhuman authority reflect each other; and psychological, because the rejection of human and divine authority, of political and religious orthodoxy, reflect each other. Thus the French Encyclopdie Anarchiste (1932) included an article on Atheism by Gustave Brocher: ‘An anarchist, who wants no all-powerful master on earth, no authoritarian government, must necessarily reject the idea of an omnipotent power to whom everything must be subjected; if he is consistent, he must declare himself an atheist.’ And the centenary issue of the British anarchist paper Freedom (October 1986) contained an article by Barbara Smoker (president of the National Secular Society) entitled ‘Anarchism implies Atheism’. -

CFI-Annual-Report-2018.Pdf

Message from the President and CEO Last year was another banner year for the Center the interests of people who embrace reason, for Inquiry. We worked our secular magic in a science, and humanism—the principles of the vast variety of ways: from saving lives of secular Enlightenment. activists around the world who are threatened It is no secret that these powerful ideas like with violence and persecution to taking the no others have advanced humankind by nation’s largest drugstore chain, CVS, to court unlocking human potential, promoting goodness, for marketing homeopathic snake oil as if it’s real and exposing the true nature of reality. If you medicine. are looking for humanity’s true salvation, CFI stands up for reason and science in a way no look no further. other organization in the country does, because This past year we sought to export those ideas to we promote secular and humanist values as well places where they have yet to penetrate. as scientific skepticism and critical thinking. The Translations Project has taken the influential But you likely already know that if you are reading evolutionary biology and atheism books of this report, as it is designed with our supporters in Richard Dawkins and translated them into four mind. We want you not only to be informed about languages dominant in the Muslim world: Arabic, where your investment is going; we want you to Urdu, Indonesian, and Farsi. They are available for take pride in what we have achieved together. free download on a special website. It is just one When I meet people who are not familiar with CFI, of many such projects aimed at educating people they often ask what it is we do. -

“In God We Trust:” the US National Motto and the Contested Concept of Civil Religion

religions Article “In God We Trust:” The U.S. National Motto and the Contested Concept of Civil Religion Michael Lienesch Department of Political Science, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3265, USA; [email protected] Received: 12 April 2019; Accepted: 20 May 2019; Published: 25 May 2019 Abstract: In this essay, “In God We Trust”, the official motto of the United States, is discussed as an illustration of the contested character of American civil religion. Applying and evaluating assumptions from Robert N. Bellah and his critics, a conceptual history of the motto is presented, showing how from its first appearance to today it has inspired debates about the place of civil religion in American culture, law, and politics. Examining these debates, the changing character of the motto is explored: its creation as a religious response to the Civil War; its secularization as a symbol on the nation’s currency at the turn of the twentieth century; its state-sponsored institutionalization during the Cold War; its part in the litigation that challenged the constitutionality of civil religious symbolism in the era of the culture wars; and its continuing role in the increasingly partisan political battles of our own time. In this essay, I make the case that, while seemingly timeless, the meaning of the motto has been repeatedly reinterpreted, with culture, law, and politics interacting in sometimes surprising ways to form one of the nation’s most commonly accepted and frequently challenged symbols. In concluding, I speculate on the future of the motto, as well as on the changing place of civil religion in a nation that is increasingly pluralistic in its religion and polarized in its politics. -

Freethought Society, : Civil Action No

Case 3:15-cv-00833-MEM Document 86 Filed 07/09/18 Page 1 of 34 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT MIDDLE DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA NORTHEASTERN PENNSYLVANIA : FREETHOUGHT SOCIETY, : CIVIL ACTION NO. 3:15-833 Plaintiff : (JUDGE MANNION) v. : COUNTY OF LACKAWANNA : TRANSIT SYSTEM, : Defendant : MEMORANDUM The saying has been around since at least the 1800's: “Never discuss religion or politics with those who hold opinions opposite to yours; they are subjects that heat in handling, until they burn your fingers; . .”1 Even Linus van Pelt has acknowledged: “There are three things I have learned never to discuss with people . religion, politics and the Great Pumpkin!”2 Certainly, topics such as religion and politics have been deemed controversial for ages, but can the government prohibit advertising about such topics in public transit advertising spaces without violating the First Amendment? 115 February 1840, The Corsair, “The Letter Bag of the Great Western,” pg. 775, col. 1. 2PEANUTS by Charles M. Schulz, October 25, 1961. 1 Case 3:15-cv-00833-MEM Document 86 Filed 07/09/18 Page 2 of 34 The First Amendment prohibits the government from “abridging the freedom of speech.” U.S. CONST. AMEND. I. However, courts have differed on how that guarantee applies when private speech occurs on government property. Depending on the forum in which the speech occurs -- a traditional public forum, a designated forum, or a limited (or nonpublic) forum -- private speech is afforded different levels of protection. One particular area that has frustrated the courts is how to distinguish between designated and limited public forums. -

Contesting Tradition and Combating Intolerance a History of Free Thought in Kansas

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for Fall 2000 Contesting Tradition And Combating Intolerance A History Of Free thought In Kansas Aaron K. Ketchell University of Kansas, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Ketchell, Aaron K., "Contesting Tradition And Combating Intolerance A History Of Free thought In Kansas" (2000). Great Plains Quarterly. 2129. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/2129 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. CONTESTING TRADITION AND COMBATING INTOLERANCE A HISTORY OF FREETHOUGHT IN KANSAS AARON K. KETCHELL Diversity is the hallmark of freethought in Although the attitudes of freethinkers toward Kansas, for freethinkers were never a homoge religion are the primary concern of this essay, neous body. The movement was not only reli it must be remembered that freethinkers had gious, or for that matter, antireligious, different ideas about what the movement although the majority of social and political meant and that opposition to organized reli issues that it addressed had religious ground gion was only one, but a crucial element of the ing. No one specific organized group domi freethought agenda. nated historical Kansas freethinking. Instead, In order to understand the history of individuals in the form of editors of various freethought in Kansas one must first define newspapers, journals, and book series became the movement and its ideology. -

What Is Atheism, Secularism, Humanism? Academy for Lifelong Learning Fall 2019 Course Leader: David Eller

What is Atheism, Secularism, Humanism? Academy for Lifelong Learning Fall 2019 Course leader: David Eller Course Syllabus Week One: 1. Talking about Theism and Atheism: Getting the Terms Right 2. Arguments for and Against God(s) Week Two: 1. A History of Irreligion and Freethought 2. Varieties of Atheism and Secularism: Non-Belief Across Cultures Week Three: 1. Religion, Non-religion, and Morality: On Being Good without God(s) 2. Explaining Religion Scientifically: Cognitive Evolutionary Theory Week Four: 1. Separation of Church and State in the United States 2. Atheist/Secularist/Humanist Organization and Community Today Suggested Reading List David Eller, Natural Atheism (American Atheist Press, 2004) David Eller, Atheism Advanced (American Atheist Press, 2007) Other noteworthy readings on atheism, secularism, and humanism: George M. Smith Atheism: The Case Against God Richard Dawkins The God Delusion Christopher Hitchens God is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything Daniel Dennett Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon Victor Stenger God: The Failed Hypothesis Sam Harris The End of Faith: Religion, Terror, and the Future of Religion Michael Martin Atheism: A Philosophical Justification Kerry Walters Atheism: A Guide for the Perplexed Michel Onfray In Defense of Atheism: The Case against Christianity, Judaism, and Islam John M. Robertson A Short History of Freethought Ancient and Modern William Lane Craig and Walter Sinnott-Armstrong God? A Debate between a Christian and an Atheist Phil Zuckerman and John R. Shook, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Secularism Janet R. Jakobsen and Ann Pellegrini, eds. Secularisms Callum G. Brown The Death of Christian Britain: Understanding Secularisation 1800-2000 Talal Asad Formations of the Secular: Christianity, Islam, Modernity Lori G. -

Charlotte Wilson, the ''Woman Question'', and the Meanings of Anarchist Socialism in Late Victorian Radicalism

IRSH, Page 1 of 34. doi:10.1017/S0020859011000757 r 2011 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis Charlotte Wilson, the ‘‘Woman Question’’, and the Meanings of Anarchist Socialism in Late Victorian Radicalism S USAN H INELY Department of History, State University of New York at Stony Brook E-mail: [email protected] SUMMARY: Recent literature on radical movements in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries has re-cast this period as a key stage of contemporary globali- zation, one in which ideological formulations and radical alliances were fluid and did not fall neatly into the categories traditionally assigned by political history. The following analysis of Charlotte Wilson’s anarchist political ideas and activism in late Victorian Britain is an intervention in this new historiography that both supports the thesis of global ideological heterogeneity and supplements it by revealing the challenge to sexual hierarchy that coursed through many of these radical cross- currents. The unexpected alliances Wilson formed in pursuit of her understanding of anarchist socialism underscore the protean nature of radical politics but also show an over-arching consensus that united these disparate groups, a common vision of the socialist future in which the fundamental but oppositional values of self and society would merge. This consensus arguably allowed Wilson’s gendered definition of anarchism to adapt to new terms as she and other socialist women pursued their radical vision as activists in the pre-war women’s movement. INTRODUCTION London in the last decades of the nineteenth century was a global crossroads and political haven for a large number of radical activists and theorists, many of whom were identified with the anarchist school of socialist thought. -

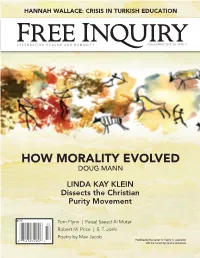

How Morality Evolved Doug Mann

HANNAH WALLACE: CRISIS IN TURKISH EDUCATION CELEBRATING REASON AND HUMANITY February/March 2019 Vol. 39 No. 2 HOW MORALITY EVOLVED DOUG MANN LINDA KAY KLEIN Dissects the Christian Purity Movement F/M 17 $5.95 CDN $5.95 US $5.95 Tom Flynn | Faisal Saeed Al Mutar 03 Robert M. Price | S. T. Joshi Poetry by Max Jacob Published by the Center for Inquiry in association 0 74470 74957 8 with the Council for Secular Humanism For many, mere atheism (the absence of belief in gods and the supernatural) or agnosticism (the view that such questions cannot be answered) aren’t enough. It’s liberating to recognize that supernatural beings are human creations … that there’s no such thing as “spirit” or “transcendence”… that people are undesigned, unintended, and responsible for themselves. But what’s next? Atheism and agnosticism are silent on larger questions of values and meaning. If Meaning in life is not ordained from on high, what small-m meanings can we work out among ourselves? If eternal life is an illusion, how can we make the most of our only lives? As social beings sharing a godless world, how should we coexist? For the questions that remain unanswered after we’ve cleared our minds of gods and souls and spirits, many atheists, agnostics, skeptics, and freethinkers turn to secular humanism. Secular. “Pertaining to the world or things not spiritual or sacred.” Humanism. “Any system of thought or action concerned with the interests or ideals of people … the intellectual and cultural movement … characterized by an emphasis on human interests rather than … religion.” — Webster’s Dictionary Secular humanism is a comprehensive, nonreligious life stance incorporating: A naturalistic philosophy A cosmic outlook rooted in science, and A consequentialist ethical system in which acts are judged not by their conformance to preselected norms but by their consequences for men and women in the world.