Scientism, Humanism, and Religion: the New Atheism and the Rise of the Secular Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

More Visible but Limited in Its Popularity Atheism (And Atheists) in Finland

TEEMU TAIRA More visible but limited in its popularity Atheism (and atheists) in Finland his paper argues that atheism has become more atheism has become more visible in the public sphere, visible in Finland, but it is a relatively unpopular especi ally in the media. Some suggestions will be of Tidentity position. The relatively low popularity of fered as to why this is the case. This will be done by atheism is partly explained by the connection between using different kinds of data, both quantitative (sur Lutheranism and Finnishness. In public discourse athe- veys) and qualitative (mainly media outputs). ism has been historically connected to communism This paper proceeds as follows. First, surveys and the Soviet Union (and, therefore, anti-Finnishness). about Finnish religiosity and atheism will be exam However, atheism has slowly changed from being the ined in order to chart the modes and locations of other of Finnishness to one alternative identity among Finnish nonreligiosity. This section is based on a many, although it has not become extremely popular. fairly detailed exploration of surveys, including an Recently, with the rise of the so-called ‘New Atheism’, examination of the popularity of religious beliefs, re atheism has become more visible in Finnish society and ligious behaviour, membership and identification in this development has led to a polarised debate between Finland. It demonstrates that atheism is relatively un defenders and critics of religion. Despite being a study popular in Finland, despite the low level of religious on locality, the aim is to develop a methodological ap- activity. In order to examine why this is the case, pub proach that can be applied to other contexts. -

Atheism” in America: What the United States Could Learn from Europe’S Protection of Atheists

Emory International Law Review Volume 27 Issue 1 2013 Redefining A" theism" in America: What the United States Could Learn From Europe's Protection of Atheists Alan Payne Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/eilr Recommended Citation Alan Payne, Redefining A" theism" in America: What the United States Could Learn From Europe's Protection of Atheists, 27 Emory Int'l L. Rev. 661 (2013). Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/eilr/vol27/iss1/14 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Emory Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Emory International Law Review by an authorized editor of Emory Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PAYNE GALLEYSPROOFS1 7/2/2013 1:01 PM REDEFINING “ATHEISM” IN AMERICA: WHAT THE UNITED STATES COULD LEARN FROM EUROPE’S PROTECTION OF ATHEISTS ABSTRACT There continues to be a pervasive and persistent stigma against atheists in the United States. The current legal protection of atheists is largely defined by the use of the Establishment Clause to strike down laws that reinforce this stigma or that attempt to deprive atheists of their rights. However, the growing atheist population, a religious pushback against secularism, and a neo- Federalist approach to the religion clauses in the Supreme Court could lead to the rights of atheists being restricted. This Comment suggests that the United States could look to the legal protections of atheists in Europe. Particularly, it notes the expansive protection of belief, thought, and conscience and some forms of establishment. -

Atheism AO2 Handout Part 1

Philosophy Of Religion / Atheism AO2 Atheism AO2 Handout Part 1 New Atheism successfully shows the incompatibility of science and religion. Evaluate this view. 1. New Atheists seem to argue that scientific theories are based only on evidence, whilst religion runs away from evidence. The claim is that atheism is rational and scientific while religion is irrational and superstitious. Faith is not an element of science since evidence for a correct conviction compels us to accept its truth. As Dawkins says “Faith is a state of mind that leads people to believe something – it doesn’t matter what – in the total absence of supporting evidence. If there were good supporting evidence, then faith would be superfluous…” However, Alister McGrath points out that such a view “fails to make the critical distinction between the ‘total absence of supporting evidence’ and the ‘absence of totally supporting evidence’.” It is true that some facts about the world have been proved (e.g. the chemical formula for water) but the bigger scientific questions such as is there a Grand Unified Theory that explains everything rely on answers based on the best evidence available but they are not certainties. In future years they may well change as new evidence is considered. As Gauch concluded “Science rests on faith”. Dawkins in his book “The God Delusion” does argue that the existence of God is a testable hypothesis and concludes that the hypothesis is falsifiable. Therefore the hypothesis is open to the scientific method. So here is a New Atheist proponent arguing that that the existence of God is a meaningful hypothesis. -

PAUL KURTZ in MEMORIAM Paul Kurtz, Philosopher, Humanist Leader, and Founder of the Modern Skeptical Movement, Dies at Eighty-Six TOM FLYNN

Jan Feb 13 2_SI new design masters 11/29/12 11:26 AM Page 5 [ PAUL KURTZ IN MEMORIAM Paul Kurtz, Philosopher, Humanist Leader, and Founder of the Modern Skeptical Movement, Dies at Eighty-Six TOM FLYNN Paul Kurtz, founder and longtime chair At NYU Kurtz studied philosophy of the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry, under Sidney Hook, who had himself the Council for Secular Humanism, and been a protégé of the pragmatist philoso- the Center for Inquiry, died at the age pher John Dewey. The philosophy of of eighty-six on October 20, 2012. He Dewey and Hook, arguably the greatest was one of the most influential figures American thinkers in the humanist tra- in the humanist and skeptical move- dition, would deeply in fluence Kurtz’s ments from the late 1960s through the thought and activism. Kurtz graduated first decade of the twenty-first century. from NYU in 1948 and earned his PhD Among his best-known creations are in philosophy at Columbia University in the skeptics’ magazine SKEPTICAL IN- 1952. QUIRER, the secular humanist magazine Free Inquiry, and the independent pub- Academic Career lisher Prometheus Books. Kurtz taught philosophy at Trinity Col- Jonathan Kurtz, Paul’s son, told SI that lege from 1952 to 1959. He joined the his father had a “‘joyous’ last day, joking, faculty at Union College from 1961 to laughing, etc. He then died suddenly to- 1965; during this period he was also a ward bedtime. There was no suffering.” A visiting lecturer at the New School for joint CFI/CSI/CSH statement marked Social Research. -

Translation Ellehumanist Ur S

. ! se rv ic e e a m n p d a t p hy a r t i c i a p l a tr t i u o is n m ility um h – e t h ic a l d e v e l o p m e n t peace and ice l just cia so critical thinking responsibility s gl s ob e al awaren e n vironmental ism ، American Humanist Association: www.americanhumanist.org Humanist Manifesto: www.americanhumanist.org/what-is-humanism/manifesto3/ The Ten Commitments: www.humanistcommitments.org Effective Altruism: https://www.effectivealtruism.org Camp Quest: www.campquest.org Foundation Beyond Belief: https://foundationbeyondbelief.org Oasis: www.networkoasis.org Sunday Assembly: www.sundayassembly.com Unitarian Universalist Association: www.UUA.org Center For Inquiry: www.centerforinquiry.org Freedom From Religion Foundation: www.ffrf.org American Ethical Union: www.aeu.org Secular Student Alliance: www.secularstudents.org Skeptic Society: https://www.skeptic.com Black Non-Believers www.blacknonbelievers.com Hispanic American Freethinkers: http://hafree.org Freethought Society: www.ftsociety.org Friendly Atheist: www.friendlyatheist.patheos.com Thinking Atheist: www.thethinkingatheist.com American Atheists: www.atheists.org Annabelle & Aiden Book Series: www.annabelleandaiden.com Stardust Book Series: www.stardustscience.com Society for Humanistic Judaism: www.shj.org Openly Secular: www.openlysecular.org Secular Coalition: www.secular.org Teacher Institute for Evolutionary Science: www.tieseducation.org Richard Dawkins Foundation: www.richarddawkins.net Humanists International: www.humanists.international Humanist Community -

A Short Course on Humanism

A Short Course On Humanism © The British Humanist Association (BHA) CONTENTS About this course .......................................................................................................... 5 Introduction – What is Humanism? ............................................................................. 7 The course: 1. A good life without religion .................................................................................... 11 2. Making sense of the world ................................................................................... 15 3. Where do moral values come from? ........................................................................ 19 4. Applying humanist ethics ....................................................................................... 25 5. Humanism: its history and humanist organisations today ....................................... 35 6. Are you a humanist? ............................................................................................... 43 Further reading ........................................................................................................... 49 33588_Humanism60pp_MH.indd 1 03/05/2013 13:08 33588_Humanism60pp_MH.indd 2 03/05/2013 13:08 About this course This short course is intended as an introduction for adults who would like to find out more about Humanism, but especially for those who already consider themselves, or think they might be, humanists. Each section contains a concise account of humanist The unexamined life thinking and a section of questions -

Humanism in America Today

Humanism Humanism in America Today Humanism in America Today Summary: Writers and public figures with large audiences have contributed to the increasing popularity of atheism and Humanism in the United States. Thousands of people attended the 2012 Reason Rally, demonstrating the rise of atheism as a political movement, yet many atheists and Humanists experience marginalization within American culture and the challenge of translating a mostly intellectual doctrine into a social movement. On a rainy day in March of 2012, roughly 20,000 people from all parts of the Humanist, atheist, and freethinking movements converged on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. They gathered to celebrate secular values, dispel stereotypes about secular people, and support secular equality. Sponsored by twenty of the country’s major secular organizations, the Reason Rally featured live music and remarks from academics, bloggers, student activists, media personalities, comedians, and two members of Congress, including Representative Pete Stark (D-CA), the first openly atheistic member of Congress. The Reason Rally is evidence of a growing energy and excitement among atheists in America. This new visibility of secularism was inspired in part by the “New Atheists”—including authors such as Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris and Christopher Hitchens—who have pushed the discussion of the potentially dangerous aspects of religion to the forefront of the public discussion. More people than ever are turning away from traditional religious faith, with the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life reporting that, as of 2014, some 20% of the US population identify as “unaffiliated.” This is particularly true of the rising millennial generation, which has increasingly come to view institutional and traditional religion as associated with conservative social views such as opposition to gay marriage, and is therefore much more skeptical of the role of religion in public life than their parents and grandparents. -

Religion and Public Reasons Works of John Finnis Available from Oxford University Press

Religion and Public Reasons Works of John Finnis available from Oxford University Press Reason in Action Collected Essays: Volume I Intention and Identity Collected Essays: Volume II Human Rights and Common Good Collected Essays: Volume III Philosophy of Law Collected Essays: Volume IV Religion and Public Reasons Collected Essays: Volume V Natural Law and Natural Rights Second Edition Aquinas Moral, Political, and Legal Theory Nuclear Deterrence, Morality and Realism with Joseph Boyle and Germain Grisez RELIGION AND PUBLIC REASONS Collected Essays: Volume V John Finnis 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX2 6DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offi ces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © J. M. Finnis, 2011 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Crown Copyright material reproduced with the permission of the Controller, HMSO (under the terms of the Click Use licence) Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2011 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. -

A Contextual Examination of Three Historical Stages of Atheism and the Legality of an American Freedom from Religion

ABSTRACT Rejecting the Definitive: A Contextual Examination of Three Historical Stages of Atheism and the Legality of an American Freedom from Religion Ethan Gjerset Quillen, B.A., M.A., M.A. Mentor: T. Michael Parrish, Ph.D. The trouble with “definitions” is they leave no room for evolution. When a word is concretely defined, it is done so in a particular time and place. Contextual interpretations permit a better understanding of certain heavy words; Atheism as a prime example. In the post-modern world Atheism has become more accepted and popular, especially as a reaction to global terrorism. However, the current definition of Atheism is terribly inaccurate. It cannot be stated properly that pagan Atheism is the same as New Atheism. By interpreting the Atheisms from four stages in the term‟s history a clearer picture of its meaning will come out, hopefully alleviating the stereotypical biases weighed upon it. In the interpretation of the Atheisms from Pagan Antiquity, the Enlightenment, the New Atheist Movement, and the American Judicial and Civil Religious system, a defense of the theory of elastic contextual interpretations, rather than concrete definitions, shall be made. Rejecting the Definitive: A Contextual Examination of Three Historical Stages of Atheism and the Legality of an American Freedom from Religion by Ethan Gjerset Quillen, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Approved by the J.M. Dawson Institute of Church-State Studies ___________________________________ Robyn L. Driskell, Ph.D., Interim Chairperson Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved by the Thesis Committee ___________________________________ T. -

CFI-Annual-Report-2018.Pdf

Message from the President and CEO Last year was another banner year for the Center the interests of people who embrace reason, for Inquiry. We worked our secular magic in a science, and humanism—the principles of the vast variety of ways: from saving lives of secular Enlightenment. activists around the world who are threatened It is no secret that these powerful ideas like with violence and persecution to taking the no others have advanced humankind by nation’s largest drugstore chain, CVS, to court unlocking human potential, promoting goodness, for marketing homeopathic snake oil as if it’s real and exposing the true nature of reality. If you medicine. are looking for humanity’s true salvation, CFI stands up for reason and science in a way no look no further. other organization in the country does, because This past year we sought to export those ideas to we promote secular and humanist values as well places where they have yet to penetrate. as scientific skepticism and critical thinking. The Translations Project has taken the influential But you likely already know that if you are reading evolutionary biology and atheism books of this report, as it is designed with our supporters in Richard Dawkins and translated them into four mind. We want you not only to be informed about languages dominant in the Muslim world: Arabic, where your investment is going; we want you to Urdu, Indonesian, and Farsi. They are available for take pride in what we have achieved together. free download on a special website. It is just one When I meet people who are not familiar with CFI, of many such projects aimed at educating people they often ask what it is we do. -

Vision of Universal Identity in World Religions: from Life-Incoherent to Life- Grounded Spirituality – John Mcmurtry

PHILOSOPHY AND WORLD PROBLEMS – Vision of Universal Identity in World Religions: From Life-Incoherent to Life- Grounded Spirituality – John McMurtry VISIONS OF UNIVERSAL IDENTITY IN WORLD RELIGIONS: FROM LIFE-INCOHERENT TO LIFE-GROUNDED SPIRITUALITY John McMurtry University of Guelph,Guelph NIG 2W1, Canada Keywords: atman, breath, Buddhism, capitalist religion, civil commons, death, dream model, dualities, externalist fallacy, false religion, God, the Great Round, I- consciousness, idolatry, illusionism, integral yoga, invisible hand, incentives, Islam, Jesus, Krishna, Lao, life necessities/needs, life-coherence principle, prophets, sacrifice levels, self/self-group, social orders, spiritual ecology, structures of life blindness, suffering, Sufis, sustainability, Tantric, theo-capitalism, Vedas/Vedanta, war Contents 1. Understanding False Religion across History and Cultures 1.1 Spiritual Consciousness versus False Religion 1.2 Variations of Sacrificial Theme 1.3 The Unseen Contradictions 2. From Life Sacrifice for Selfish Gain to Offerings for Renewal of the Great Round 2.1. Sustainability of Life Systems versus Sustainability of Profit 3. The Animating Breath of Life: The Unseen Common Ground of the Spiritual Across Religions 4. Sacrificing Self to Enable Life across Divisions: The Ancient Spiritual Vision 5. What Is the I That Has a Body? Rational Explanation of the Infinite Consciousness Within 6. Counter-Argument: How Analytic Philosophy and Science Explain Away Inner Life 7. From the Soul of the Upanishads to the Ecology of Universal Life Identity 8. Reconnecting Heaven to Earth: The Inner-Outer Infinitude of Spiritual Comprehension 9. Re-Grounding Spirituality: From the Light-Fields to Universal Life Necessities 9.1. Why the Buddhist Reformation of Hinduism Still Does Not Solve the Problem 9.2. -

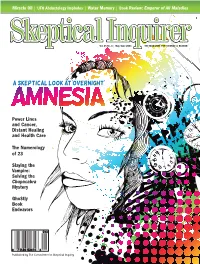

A Skeptical Look at Overnight

SI May June 2011_SI JF 10 V1 3/25/11 11:53 AM Page 1 Miracle Oil | UFO Abductology Implodes | Water Memory | Book Review: Emperor of All Maladies Vol. 35 No. 3 | May/June 2011 THE MAGAZINE FOR SCIENCE & REASON A Skeptical Look At Overnight Power Lines and Cancer, Distant Healing and Health Care The Numerology of 23 Slaying the Vampire: Solving the Chupacabra Mystery Gho$tly Book Endeavors Published by The Committee for Skeptical Inquiry SI May June 11 CUT_SI new design masters 3/25/11 10:01 AM Page 2 AT THE CEN TERFOR IN QUIRY /TRANSNATIONAL www.csicop.org Paul Kurtz, Founder Joe Nickell, Senior Research Fellow Richard Schroeder, Chairman Massimo Polidoro, Research Fellow Ronald A. Lindsay, President and CEO Benjamin Radford, Research Fellow Bar ry Karr, Ex ec u tive Di rect or Richard Wiseman, Research Fellow James E. Al cock*, psy chol o gist, York Univ., Tor on to Thom as Gi lov ich, psy chol o gist, Cor nell Univ. Lor en Pan kratz, psy chol o gist, Or e gon Health Mar cia An gell, MD, former ed i tor-in-chief, Wendy M. Grossman, writer; founder and first editor, Sci en ces Univ. New Eng land Jour nal of Med i cine The Skeptic magazine (UK) Robert L. Park,professor of physics, Univ. of Maryland Kimball Atwood IV, MD, physician, author, Sus an Haack, Coop er Sen ior Schol ar in Arts and Jay M. Pasachoff, Field Memorial Professor of Newton, MA Sci en ces, professor of phi los o phy and professor Astronomy and director of the Hopkins Steph en Bar rett, MD, psy chi a trist, au thor, con sum er of Law, Univ.