Duan-Xiaoxuan-ACAS-Finalized.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY An Jingfu (1994) The Pain of a Half Taoist: Taoist Principles, Chinese Landscape Painting, and King of the Children . In Linda C. Ehrlich and David Desser (eds.). Cinematic Landscapes: Observations on the Visual Arts and Cinema of China and Japan . Austin: University of Texas Press, 117–25. Anderson, Marston (1990) The Limits of Realism: Chinese Fiction in the Revolutionary Period . Berkeley: University of California Press. Anon (1937) “Yueyu pian zhengming yundong” [“Jyutpin zingming wandung” or Cantonese fi lm rectifi cation movement]. Lingxing [ Ling Sing ] 7, no. 15 (June 27, 1937): no page. Appelo, Tim (2014) ‘Wong Kar Wai Says His 108-Minute “The Grandmaster” Is Not “A Watered-Down Version”’, The Hollywood Reporter (6 January), http:// www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/wong-kar-wai-says-his-668633 . Aristotle (1996) Poetics , trans. Malcolm Heath (London: Penguin Books). Arroyo, José (2000) Introduction by José Arroyo (ed.) Action/Spectacle: A Sight and Sound Reader (London: BFI Publishing), vii-xv. Astruc, Alexandre (2009) ‘The Birth of a New Avant-Garde: La Caméra-Stylo ’ in Peter Graham with Ginette Vincendeau (eds.) The French New Wave: Critical Landmarks (London: BFI and Palgrave Macmillan), 31–7. Bao, Weihong (2015) Fiery Cinema: The Emergence of an Affective Medium in China, 1915–1945 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press). Barthes, Roland (1968a) Elements of Semiology (trans. Annette Lavers and Colin Smith). New York: Hill and Wang. Barthes, Roland (1968b) Writing Degree Zero (trans. Annette Lavers and Colin Smith). New York: Hill and Wang. Barthes, Roland (1972) Mythologies (trans. Annette Lavers), New York: Hill and Wang. © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 203 G. -

Art, Politics, and Commerce in Chinese Cinema

Art, Politics, and Commerce in Chinese Cinema edited by Ying Zhu and Stanley Rosen Hong Kong University Press 14/F Hing Wai Centre, 7 Tin Wan Praya Road, Aberdeen, Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © Hong Kong University Press 2010 Hardcover ISBN 978-962-209-175-7 Paperback ISBN 978-962-209-176-4 All rights reserved. Copyright of extracts and photographs belongs to the original sources. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the copyright owners. Printed and bound by XXXXX, Hong Kong, China Contents List of Tables vii Acknowledgements ix List of Contributors xiii Introduction 1 Ying Zhu and Stanley Rosen Part 1 Film Industry: Local and Global Markets 15 1. The Evolution of Chinese Film as an Industry 17 Ying Zhu and Seio Nakajima 2. Chinese Cinema’s International Market 35 Stanley Rosen 3. American Films in China Prior to 1950 55 Zhiwei Xiao 4. Piracy and the DVD/VCD Market: Contradictions and Paradoxes 71 Shujen Wang Part 2 Film Politics: Genre and Reception 85 5. The Triumph of Cinema: Chinese Film Culture 87 from the 1960s to the 1980s Paul Clark vi Contents 6. The Martial Arts Film in Chinese Cinema: Historicism and the National 99 Stephen Teo 7. Chinese Animation Film: From Experimentation to Digitalization 111 John A. Lent and Ying Xu 8. Of Institutional Supervision and Individual Subjectivity: 127 The History and Current State of Chinese Documentary Yingjin Zhang Part 3 Film Art: Style and Authorship 143 9. -

1St China Onscreen Biennial

2012 1st China Onscreen Biennial LOS ANGELES 10.13 ~ 10.31 WASHINGTON, DC 10.26 ~ 11.11 Presented by CONTENTS Welcome 2 UCLA Confucius Institute in partnership with Features 4 Los Angeles 1st China Onscreen UCLA Film & Television Archive All Apologies Biennial Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Are We Really So Far from the Madhouse? Film at REDCAT Pomona College 2012 Beijing Flickers — Pop-Up Photography Exhibition and Film Seeding cross-cultural The Cremator dialogue through the The Ditch art of film Double Xposure Washington, DC Feng Shui Freer and Sackler Galleries of the Smithsonian Institution Confucius Institute at George Mason University Lacuna — Opening Night Confucius Institute at the University of Maryland The Monkey King: Uproar in Heaven 3D Confucius Institute Painted Skin: The Resurrection at Mason 乔治梅森大学 孔子学院 Sauna on Moon Three Sisters The 2012 inaugural COB has been made possible with Shorts 17 generous support from the following Program Sponsors Stephen Lesser The People’s Secretary UCLA Center for Chinese Studies Shanghai Strangers — Opening Night UCLA Center for Global Management (CGM) UCLA Center for Management of Enterprise in Media, Entertainment and Sports (MEMES) Some Actions Which Haven’t Been Defined Yet in the Revolution Shanghai Jiao Tong University Chinatown Business Improvement District Mandarin Plaza Panel Discussion 18 Lois Lambert of the Lois Lambert Gallery Film As Culture | Culture in Film Queer China Onscreen 19 Our Story: 10 Years of Guerrilla Warfare of the Beijing Queer Film Festival and -

Olga Bobrowska Towarzysz Te Wei

Olga Bobrowska Towarzysz Te Wei Media – Kultura – Komunikacja Społeczna 10/2, 105-123 2014 Olga Bobrowska Towarzysz Te Wei Słowa kluczowe: Te Wei, szanghajska szkoła animacji, Szaghajskie Studio Filmów Ani mowanych, styl minzu, manhua, animacja tuszu i wody Key words: Te Wei, Shanghai School of Animation, Shanghai Animation Film Studio, min zu style, manhua, ink-wash animation O Te Weiu, nestorze chińskiego filmu animowanego cieszącym się między narodowym uznaniem i estymą, w ramach zachodnich studiów nad animacją napisano niewiele. Sytuacja ta jest jednocześnie zaskakująca i zrozumiała. Budzi ona zdziwienie, jeżeli wziąć pod uwagę fakt, że twórczość Te Weia do strzeżono na Zachodzie już w latach sześćdziesiątych XX wieku, a samego artystę (jako jedynego spośród chińskich twórców) w 1995 roku odznaczono prestiżową nagrodą ASIFA za życiowe osiągnięcia. Przez niemal trzy dekady (lata 1957-1984, z wyłączeniem okresu Rewolucji Kulturalnej) kierował on działalnością jedynej chińskiej wytwórni filmów animowanych w Szanghaju (Shanghai Animation Film Studio, SAFS), wytyczając kierunki artystycznego i politycznego rozwoju chińskiego filmu animowanego. Niewielka, bowiem zło żona z siedmiu tytułów, filmografia stanowi „lekturę obowiązkową” nie tylko dla zainteresowanych klasycznym okresem animacji w ChRL-u (lata 1957 -1965, 1976-1989), ale dla wszystkich, których fascynuje niemal stuletnia już historia filmu animowanego w Państwie Środka1. Nieliczne publikacje anglojęzycznych filmoznawców z zakresu badań nad chińskim filmem animowanym pojawiają się jako rozdziały w pracach zbiorowych2 lub artykuły w czasopismach3. Także Encyclopedia of Chinese F ilm poświęca tej tematyce zaledwie cztery krótkie hasła4. Można zauważyć, 1 Nie zachowała się żadna kopia chińskiego filmu animowanego sprzed 1940 roku. Pio nierami i innowatorami filmu animowanego w Chinach byli bracia Wan z Nankinu (Laiming [1899-1997], Guchan [1899-1995], Chaochen [1906-1992] i Dihuan [ur. -

Chinese Literature in the Second Half of a Modern Century: a Critical Survey

CHINESE LITERATURE IN THE SECOND HALF OF A MODERN CENTURY A CRITICAL SURVEY Edited by PANG-YUAN CHI and DAVID DER-WEI WANG INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS • BLOOMINGTON AND INDIANAPOLIS William Tay’s “Colonialism, the Cold War Era, and Marginal Space: The Existential Condition of Five Decades of Hong Kong Literature,” Li Tuo’s “Resistance to Modernity: Reflections on Mainland Chinese Literary Criticism in the 1980s,” and Michelle Yeh’s “Death of the Poet: Poetry and Society in Contemporary China and Taiwan” first ap- peared in the special issue “Contemporary Chinese Literature: Crossing the Bound- aries” (edited by Yvonne Chang) of Literature East and West (1995). Jeffrey Kinkley’s “A Bibliographic Survey of Publications on Chinese Literature in Translation from 1949 to 1999” first appeared in Choice (April 1994; copyright by the American Library Associ- ation). All of the essays have been revised for this volume. This book is a publication of Indiana University Press 601 North Morton Street Bloomington, IN 47404-3797 USA http://www.indiana.edu/~iupress Telephone orders 800-842-6796 Fax orders 812-855-7931 Orders by e-mail [email protected] © 2000 by David D. W. Wang All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses’ Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences— Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. -

Newsletter 13

Prelude to the Opening: Integrating Wares Hard and Soft The construction of the Hong Kong Film Archive building has finally been completed. In August, we bid farewell to our Planning Office and moved into the new building. All sections of the Archive are busy working with each other to make sure that the new environment will serve as an effective site for the preservation and promotion of our film culture. The Administration Section has shouldered the responsibility of coordinating the relocation, from supervising the progress of construction to purchasing furnishings. While the Conservation Section is testing the temperature and humidity of our storage vaults, the Cataloguing Section is shelving publications, prints and audio-visual materials as well as working with the IT Systems Section to input data of our collection into the computer system. Our new structure also includes the Programming Section, which has been established to take over the curation of screenings and exhibitions from the Research and Editorial Sections. We are putting our facilities through vigorous testing to ensure that when the Archive opens, we can share the 80-year treasures of Hong Kong cinema with the public. In what way can we expediently serve the citizens of Hong Kong and researchers of the world? In what manner do we share our collection with the public? Heads of the Programming and Conservation Sections are invited to answer these questions, providing a key to understanding our operation. We will continue to introduce other facilities and services in our coming issues. Prelude to the Opening - Some Thoughts on Assuming a New Responsibility Law Kar, HKFA Programmer The Hong Kong Film Archive has come about as a result of repeated urgings from the public. -

English Translation

Hong Kong Film Archive e-Newsletter 69 More English translation Publisher: Hong Kong Film Archive © 2014 Hong Kong Film Archive All rights reserved. No part of the content of this document may be reproduced, distributed or exhibited in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Feature In Full Bloom: The Development of Contemporary Chinese Animation (2) Fung Yuk-sung Cont’d from Newsletter Issue 68 for 1947-1976 Liberation and Creativity (1977–1989) The demise of the Gang of Four in the autumn of 1976 marked the end of the Cultural Revolution and ten years of turbulence in the country. After 1977, China implemented policies to ‘restore order after chaos,’ and also to reform and open the doors to international communication and exchange. Te Wei returned to his position as the head of the Shanghai Animation Film Studio, and Chinese animators welcomed a period of liberation, creativity and freedom of ideas. A Night in an Art Gallery, completed in 1978 and directed by A Da and others, is a fable that hints heavily at real-life events. It uses a visual style similar to that of a comic book to satirise the oppressive tyranny of the Gang of Four. It is a work that closely reflects the spirit of its times and how the people felt about the ten violent years that had just passed. A Night in an Art Gallery signified the end of a dark period and the beginning of a cultural renaissance. -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 341 5th International Conference on Arts, Design and Contemporary Education (ICADCE 2019) The Rise, Development and Turning of Chinese National Animation* Yang Zhao College of Communication Northwest Normal University Lanzhou, China Abstract—Chinese animation after 1949 has mainly first domestically produced animated film after the founding experienced three stages of development. During the of New China. After that, although Chinese animation has "Seventeen Years" Chinese animation period, the basic tone of experienced a series of political movements such as "the the development of Chinese national animation and children's three evils and the five evils", " literary and artistic animation was basically established. After 1979, with the rectification", "anti-right enlargement" and "great leap gradual opening up of animation creation ideas and the forward", it also produced animation production for deepening of foreign exchanges, Chinese national animation Shanghai Fine Arts Film Studio in individual years. Some began to show a richer and more diverse face. Beginning in the influences, such as the suspension of animation production 1990s, with the end of the national planned economy era, caused by "the three evils and the five evils" in 1951, only under the influence of animation outsourcing and foundry, a one 18 minutes animated short film "Small Iron Pillar" was large number of animation talents flowed out from the animation studios in the state-owned system, and Chinese completed in the whole year, and the literary rectification in national animation began to lose its independence, has become 1952, there was only one 15 minutes of "The Kitten Who a part of global animation production. -

"The Chinese Animation Industry: from the Mao Era to the Digital Age"

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Master's Projects and Capstones Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects Spring 5-18-2019 "The hineseC Animation Industry: from the Mao Era to the Digital Age" Stephanie Jones [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone Part of the Asian Art and Architecture Commons, Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, Chinese Studies Commons, Contemporary Art Commons, Cultural History Commons, Ethnic Studies Commons, Film Production Commons, International and Intercultural Communication Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, Language Interpretation and Translation Commons, Mass Communication Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, Other Political Science Commons, Social Influence and Political Communication Commons, Sociology of Culture Commons, Television Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Jones, Stephanie, ""The hineC se Animation Industry: from the Mao Era to the Digital Age"" (2019). Master's Projects and Capstones. 907. https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone/907 This Project/Capstone is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Projects and Capstones by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "The Chinese Animation Industry: from the Mao Era to the Digital Age" Stephanie “Maomi” Jones University of San Francisco Masters in Asian Pacific Studies Capstone Paper APS 650 Professor John Nelson 1 Abstract Since the 1950’s the Chinese Animation industry has been trying to create a unique national style for China. -

Searchable PDF Format

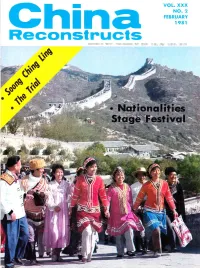

Australia: A S0 72 New Zealand: NZ S0 8:+ U K:39p U S A: S0 7E Red Rocks and Green Stream Set Ofl Each Other. l'raditional Cltirtt'yc puirtting ht Shi br PUBLISHED MONTHTY lll..FNG!!-S_!:1,_-FRENCH, SPAN_ISH,_ARABIC, GERMAN, PORTUGUESE AND cHrNEsE By THE CHINA WETFARE lNsflrurE isooNa' aHiNa"''riNd'-ti#\I[iriil, vot. xxx No.2 FEBRUARY T981 Articles of the Month Recolling One of Our Founders CONTENTS 5oon9 Ching Ling writes of lormer Politics/Low editoriol boord choirmon Jin .Zhong. huo, hounded Recalling One of Our Founders 2 to deqth by membeis of the gong ol 2 Historic Trial: lnside and Outside the Courtroom 4 four. Poge Notionolities Festival of Minority Song and Dance I Visitors' Views on the Festival 15 lnside ond Outside the Courtroom Economy Giant Project on the Changjiang (Yangtze) 20 At the triol lor Diversified Economy in 'Earthly Paradise' 30 mojor crimes ol Growing Rubber in Colder Climates 48 the ten princi. Pol members Society of the Lin Bioo- Employment and Unemployment 25 Jiong QinE cli- How One City Provided Jobs for All 28 ques. Poge I Salvaging Ships in the South China Sea 38 Foreign Commerce First U S. Trade Exhibition in China 35 Stort on Hornessing the Culture/Medio Chongjiong (Yongtze) River The Old Summer Palace, Yuan Ming Yu6n 40 China's Animated Cartoon Films 45 'Radio Peking' and lts Listeneis 57 Ihe lorgest woter conservotion Children's Books by the Hundred Million bb ond on Medicine Chino ted neor i ing Encyclopedia of Chinese Medicine 53 from uc. -

Hong Kong Film Archive E-Newsletter 68

Hong Kong Film Archive e-Newsletter 68 More English translation Publisher: Hong Kong Film Archive © 2014 Hong Kong Film Archive All rights reserved. No part of the content of this document may be reproduced, distributed or exhibited in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Feature In Full Bloom: The Development of Contemporary Chinese Animation (1) Fung Yuk-sung Introduction In the Chengxi district of Shanghai, couched between Jing’an Temple and Caojiadu, lies Wanhangdu Road, which is around 2,000 metres in length, and used to be called Jisifei’er Road. A number of intellectuals of the Republican period – Hu Shi, Feng Ziyou, Zhang Zhiji – lived here. At the south end of the road is the famed Paramount, still well known today as the most glamorous nightclub of its era. 618 Wanhangdu Road is a Western-style mansion designed like a cruise ship and was widely believed to be the property of the mayor of Shanghai during the Republic. Later it was combined with the mansion next door to the south, left behind by an Englishman, to form a film studio just over 10,000 square metres – the Shanghai Animation Film Studio. In the half-century or so, from the 1950s to the present day, this has been the largest studio for animation production in China, attracting the best people working in the industry. Although much has changed in the industry over the last 30 years since the Central Government’s economic reforms, any study of its history and development will almost certainly focus on this mecca of Chinese animation film. -

Havoc in Heaven and the Golden Age of Chinese Animation

Jiashu Hu Critical Seminar MFA Illustration Practice Havoc in Heaven and the Golden Age of Chinese Animation In March, 2013, an old Chinese Film Studio, Shanghai Animation Film Studio reclaimed that they will remake the famous Chinese old animation such as Havoc in Heaven, Mr. Black, and Brother Calabash. This is not the first time they tried to remake the glorious age of those classical animations. The 3D version Havoc in Heaven, released last year, showed the vanity of their attempt. The total box office is no more than $3 million, which can only pay for the 3D production cost by an American 3D production company. (Chen) Shanghai Animation Film studio represented the highest level of the Chinese animation and had been gained the unduplicated success. Why can’t it be glories again for Chinese animation? To find the solution to this problem, we should go back to the golden age of Chinese 1. Havoc in Heaven Animation Cover animation and research the reason for their success. The glories: Shanghai Animation Film Studio Shanghai Animation Film Studio was founded in 1957. Ten years before that, Dongbei Film Studio, which is its predecessor, made some documentaries about victory from war of liberation in Dongbei province. People in art departments have to study the most basic animation in order to make motional map for the story of the war in documentary. Those people in the art department made the earliest short animation, Emperor Dream and Catch a Turtle in the Jar, in order to satire the Kuo Ming Tang Government. Although those two animations are pretty simple, they gained good effects of publicity.