The Biography of Paul Wilson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Here to Be Objectively Apprehended

UMCSEET UNEARTHING THE MUSIC Creative Sound and Experimentation under European Totalitarianism 1957-1989 Foreword: “Did somebody say totalitarianism?” /// Pág. 04 “No Right Turn: Eastern Europe Revisited” Chris Bohn /// Pág. 10 “Looking back” by Chris Cutler /// Pág. 16 Russian electronic music: László Hortobágyi People and Instruments interview by Alexei Borisov Lucia Udvardyova /// Pág. 22 /// Pág. 32 Martin Machovec interview Anna Kukatova /// Pág. 46 “New tribalism against the new Man” by Daniel Muzyczuk /// Pág. 56 UMCSEET Creative Sound and Experimentation UNEARTHING THE MUSIC under European Totalitarianism 1957-1989 “Did 4 somebody say total- itarian- ism?” Foreword by Rui Pedro Dâmaso*1 Did somebody say “Totalitarianism”* Nietzsche famously (well, not that famously...) intuited the mechanisms of simplification and falsification that are operative at all our levels of dealing with reality – from the simplification and metaphorization through our senses in response to an excess of stimuli (visual, tactile, auditive, etc), to the flattening normalisation processes effected by language and reason through words and concepts which are not really much more than metaphors of metaphors. Words and concepts are common denominators and not – as we'd wish and believe to – precise representations of something that's there to be objectively apprehended. Did We do live through and with words though, and even if we realize their subjectivity and 5 relativity it is only just that we should pay the closest attention to them and try to use them knowingly – as we can reasonably acknowledge that the world at large does not adhere to Nietzsche’s insight - we do relate words to facts and to expressions of reality. -

Mark Alan Smith Formatted Dissertation

Copyright by Mark Alan Smith 2019 The Dissertation Committee for Mark Alan Smith Certifies that this is the approved version of the following Dissertation: To Burn, To Howl, To Live Within the Truth: Underground Cultural Production in the U.S., U.S.S.R. and Czechoslovakia in the Post World War II Context and its Reception by Capitalist and Communist Power Structures. Committee: Thomas J. Garza, Supervisor Elizabeth Richmond-Garza Neil R. Nehring David D. Kornhaber To Burn, To Howl, To Live Within the Truth: Underground Cultural Production in the U.S., U.S.S.R. and Czechoslovakia in the Post World War II Context and its Reception by Capitalist and Communist Power Structures. by Mark Alan Smith. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May, 2019 Dedication I would like to dedicate this work to Jesse Kelly-Landes, without whom it simply would not exist. I cannot thank you enough for your continued love and support. Acknowledgements I would like to thank my dissertation supervisor, Dr. Thomas J. Garza for all of his assistance, academically and otherwise. Additionally, I would like to thank the members of my dissertation committee, Dr. Elizabeth Richmond-Garza, Dr. Neil R. Nehring, and Dr. David D. Kornhaber for their invaluable assistance in this endeavor. Lastly, I would like to acknowledge the vital support of Dr. Veronika Tuckerová and Dr. Vladislav Beronja in contributing to the defense of my prospectus. -

CZECH (With Slovak)

UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD FACULTY OF MEDIEVAL AND MODERN LANGUAGES Information for the Preliminary Course in CZECH (with Slovak) 2011/2012 THE PRELIMINARY COURSE The Prelims course in “Czech (with Slovak)” is normally devoted entirely to the study of Czech – although a student competent in Slovak may translate from English into Slovak instead of Czech in the examination. (An introduction to reading Slovak is provided during the second year.) First-year teaching in Czech language and literature – in the form of university lectures, college classes/seminars and tutorials – is coordinated by: Dr James D. Naughton (St Edmund Hall) University Lecturer in Czech and Slovak email: [email protected] The timetable of classes in Michaelmas Term will be arranged at a meeting held towards the end of Freshers Week (= Noughth Week). Beginners will receive around three hours of intensive Czech language classes per week, and more advanced students will be catered for as appropriate. Students also attend a weekly lecture on Czech literature and a weekly seminar on Czech literary texts. These continue throughout the year. There will also be tutorials for essays on Czech literature; these tutorials are usually held in Hilary and Trinity Terms. A number of links to local and outside web resources for students of Czech and Slovak language and literature are provided on the following web pages: http://users.ox.ac.uk/~tayl0010/links.html http://users.ox.ac.uk/~tayl0010/czech.html Further details about the papers to be sat in the Preliminary Examination and set texts for literature are given below, followed by an introductory reading list, with recommended dictionaries, textbooks and some background reading. -

Diplomová Práce 2016

Diplomová práce 2016 Petra Veselá Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Fakulta filozofická Diplomová práce Procesy Plastic People of the Universe v kontextu totalitního režimu Petra Veselá Plzeň 2016 Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Fakulta filozofická Katedra historických věd Studijní program Historické vědy Studijní obor Moderní dějiny Diplomová práce Procesy s Plastic People of the Universe v kontextu totalitního režimu Petra Veselá Vedoucí práce: PhDr. Lukáš Novotný, Ph.D. Katedra historických věd Fakulta filozofická Západočeské univerzity v Plzni Plzeň 2016 Prohlašuji, že jsem práci zpracovala samostatně a použila jen uvedených pramenů a literatury. Plzeň, duben 2016 ……………………… Touto cestou bych ráda poděkovala PhDr. Lukáši Novotnému, Ph.D. za odborné vedení mé diplomové práce. 1. Obsah 1. Úvod ...................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Vývoj k procesům s undergroundem .................................................................................... 6 2.1 Společnost v období „normalizace“ 1969–1975 ........................................................... 6 2.2 Formování undergroundu jakožto nezávislého kulturního prostředí ............................ 8 2.3 Jednotlivé etapy undergroundu ................................................................................... 10 2.4 Vznik kapely Plastic People of the Universe a první narušení normalizace ............... 11 2.5 Postoj totalitního režimu k undergroundu .................................................................. -

Poetika Tvorby Vratislava Brabence Magisterská Diplomová Práce

Masarykova univerzita Filozofická fakulta Ústav české literatury a knihovnictví Český jazyk a literatura Bc. Klára Přibylová Poetika tvorby Vratislava Brabence Magisterská diplomová práce Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Luisa Nováková, Ph.D. 2019 Prohlašuji, že jsem diplomovou práci vypracovala samostatně s využitím uvedených pramenů a literatury. ............................................................ Bc. Klára Přibylová Děkuji Mgr. Luise Novákové, Ph.D., za její odborné připomínky, cenné rady, ochotu, trpělivost a čas, který mi věnovala během zpracování této diplomové práce. Obsah Úvod .................................................................................................................................. 5 1 Život .......................................................................................................................... 9 2 Tvorba ..................................................................................................................... 14 3 Poezie před rokem 1989 ......................................................................................... 18 Víra a náboženství .................................................................................................. 20 Příroda ..................................................................................................................... 26 Literární underground ............................................................................................. 29 4 Poezie a próza po roce 1989 .................................................................................. -

Events That Led to the Czechoslovakian Prague Spring and Its Immediate Aftermath

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 2015 Events that led to the Czechoslovakian Prague Spring and its immediate aftermath Natalie Babjukova Trinity College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Recommended Citation Babjukova, Natalie, "Events that led to the Czechoslovakian Prague Spring and its immediate aftermath". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2015. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/469 Events that led to the Czechoslovakian Prague Spring and its immediate aftermath Senior thesis towards Russian major Natalie Babjukova Spring 2015 ` The invasion of Czechoslovakia by the Soviet Union on August 21 st 1968 dramatically changed not only Czech domestic, as well as international politics, but also the lives of every single person in the country. It was an intrusion of the Soviet Union into Czechoslovakia that no one had expected. There were many events that led to the aggressive action of the Soviets that could be dated way back, events that preceded the Prague Spring. Even though it is a very recent topic, the Cold War made it hard for people outside the Soviet Union to understand what the regime was about and what exactly was wrong about it. Things that leaked out of the country were mostly positive and that is why the rest of the world did not feel the need to interfere. Even within the country, many incidents were explained using excuses and lies just so citizens would not want to revolt. Throughout the years of the communist regime people started realizing the lies they were being told, but even then they could not oppose it. -

June 2010 Issue

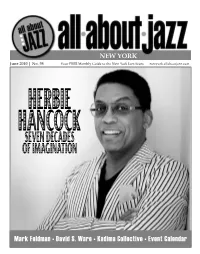

NEW YORK June 2010 | No. 98 Your FREE Monthly Guide to the New York Jazz Scene newyork.allaboutjazz.com HERBIE HANCOCKSEVEN DECADES OF IMAGINATION Mark Feldman • David S. Ware • Kadima Collective • Event Calendar NEW YORK Despite the burgeoning reputations of other cities, New York still remains the jazz capital of the world, if only for sheer volume. A night in NYC is a month, if not more, anywhere else - an astonishing amount of music packed in its 305 square miles (Manhattan only 34 of those!). This is normal for the city but this month, there’s even more, seams bursting with amazing concerts. New York@Night Summer is traditionally festival season but never in recent memory have 4 there been so many happening all at once. We welcome back impresario George Interview: Mark Feldman Wein (Megaphone) and his annual celebration after a year’s absence, now (and by Sean Fitzell hopefully for a long time to come) sponsored by CareFusion and featuring the 6 70th Birthday Celebration of Herbie Hancock (On The Cover). Then there’s the Artist Feature: David S. Ware always-compelling Vision Festival, its 15th edition expanded this year to 11 days 7 by Martin Longley at 7 venues, including the groups of saxophonist David S. Ware (Artist Profile), drummer Muhammad Ali (Encore) and roster members of Kadima Collective On The Cover: Herbie Hancock (Label Spotlight). And based on the success of the WinterJazz Fest, a warmer 9 by Andrey Henkin edition, eerily titled the Undead Jazz Festival, invades the West Village for two days with dozens of bands June. -

The Types and Functions of Samizdat Publications in Czechoslovakia, 1948–1989

The Types and Functions of Samizdat Publications in Czechoslovakia, 1948–1989 Martin Machovec Czech Literature, Charles University, Prague Abstract The term samizdat, now widespread, denotes the unofficial dissemination of any variety of text (book, magazine, leaflet, etc.) within “totalitarian” political sys- tems, especially those after World War II. Such publishing, though often not explic- itly forbidden by law, was always punishable through the misuse of a variety of laws under various pretexts. It occurred first in the Soviet Union as early as the 1920s, before the term was used, and then, labeled as such, from the 1950s onward. While samizdat publication occurred in Czechoslovakia after 1948, the word itself was used there only from the 1970s on. This article seeks to clarify the term and the phenome- non of samizdat with regard to the Czech literary scene to trace its historical limits and the justification for it. I will first describe the functions of Czech samizdat during the four decades of the totalitarian regime (1948–89), that is, examine it as a non- static, developing phenomenon, and then I will offer criteria by which to classify it. Such texts are classifiable by motivations for publishing and distributing samizdat; the originator; traditionally recognized types of printed material; date of production and of issuance, if different; textual content; occurrence in the chronology of politi- cal and cultural events under the totalitarian regime; and type of technology used in production. The applicability of such criteria is tested against the varied samizdat activities of the Czech poet and philosopher Egon Bondy. Both in Czech literary history and, as far as we know, in the literary his- tories of other countries as well there is a tendency to claim what is more or less obvious: that samizdat books, periodicals, leaflets, and recordings 1. -

Table of Contents

Table of contents 1. Prologue 3 Introduction 3 “RIO” – categorical misuse 4 A “true” progressive 4 Arnold Schonberg 7 Allan Moore 11 Bill Martin 15 2. California Outside Music Assiciation 19 The story begins 19 Coma coming out 22 Demographical setting, booking and other challenges 23 An expanding festival 23 A Beginner’s Guide 26 Outside music – avant rock 27 1980’s “Ameriprog”: creativity at the margins 29 3. The Music 33 4. Thinking Plague 37 ”Dead Silence” 37 Form and melody 37 The song ”proper” 40 Development section 42 Harmonic procedures and patterns 45 Non-functional chords and progressions 48 Polytonality: Vertical structures and linear harmony 48 Focal melodic lines and patterns 50 Musical temporality – ”the time of music” 53 Production 55 5. Motor Totemist Guild / U Totem 58 ”Ginger Tea” 62 Motives and themes 63 Harmonic patterns and procedures 67 Orchestration/instrumentation 68 Production 69 ”One Nail Draws another” and ”Ginger Tea” 70 1 6. Dave Kerman / The 5UU’s 80 Bought the farm in France… 82 Well…Not Chickenshit (to be sure…) 84 Motives and themes / harmony 85 Form 93 A precarious song foundationalism 95 Production, or: Aural alchemy - timbre as organism 99 7. Epilogue 102 Progressive rock – a definition 102 Visionary experimentalism 103 Progressive sensibility – radical affirmation and negation 104 The ”YesPistols” dialectic 105 Henry Cow: the radical predecessor 106 An astringent aesthetic 108 Rock instrumentation, -background and –history 109 Instrumental roles: shifts and expansions 109 Rock band as (chamber) orchestra – redefining instr. roles 110 Timbral exploration 111 Virtuosity: instrumental and compositional skills 114 An eclectic virtuosity 116 Technique and “anti-technique” 117 “The group’s the thing” vs. -

About the Project

Introduction About the Project This handbook is the fruit of the cooperation of a Polish-Czech-German team of re- searchers that has been working together for more than ten years. Starting on the in- itiative of Prof. em. Reinhard Ibler in May 2010, when specialists in Jewish literature, history, and culture from the universities of Giessen, Lodz, and Prague first met, the project has produced nine workshops and six publications to date. Researchers from Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznan joined the project in 2015. Our group consists mainly of Slavicists and comparative literature researchers who decided to explore the East-Central European literatures about the Holocaust and persecution of Jews during World War II, first by a chronological approach and second in terms of aesthetics.1 Throughout our meetings, we noticed a gap between the literary production of the Slavonic countries where the Holocaust mainly took place and recognition of these works outside this community. We want to increase the visibility and show the versa- tility of these literatures in the academic representation of the Holocaust in the arts. Mainly émigré authors (like Jerzy Kosinski, for his Painted Bird, 1965) received interna- tional attention because there was no language barrier right from the beginning. The underrepresentation is clear from the numbers: the Reference Guide to Holocaust Lit- erature (Young, Riggs, 2002) presents 225 authors but only two of them were of Czech origin, three of Slovak. For Polish the situation looks slightly better: 23 authors. In Ho- locaust Literature. An Encyclopedia of Writers and Their Work (Kremer, 2003), out of 312 entries, we count 31 Polish, 3 Czech, and not a single Slovak entry. -

Snow Patrol ‘Chasing Cars’

Rockschool Grade Pieces Snow Patrol ‘Chasing Cars’ Snow Patrol SONG TITLE: CHASING CARS ALBUM: EYES OPEN RELEASED: 2006 LABEL: POLYDOR GENRE: INDIE PERSONNEL: GARY LIGHTBODY (VOX+GTR) NATHAN CONNOLLY (GTR) PAUL WILSON (BASS) JONNY QUINN (DRUMS) TOM SIMPSON (KEYS) UK CHART PEAK: 6 US CHART PEAK: 5 BACKGROUND INFO NOTES ‘Chasing Cars’ is the second single from Snow Although it didn’t achieve a number 1 in the UK or Patrol’s 2006 album Eyes Open. It is a based on a the U.S. ‘Chasing Cars’ still receives massive airplay single three-chord progression, but ‘Chasing Cars’ is and can be heard almost constantly in TV shows. A far from simple. The song starts with a sparse picked moving acoustic version of ‘Chasing Cars’ appears on eighth-note guitar line which is augmented by subtle the soundtrack for the US TV show Grey’s Anatomy. keyboard parts. The arrangement uses changes in dynamics to develop the song. The third chorus sees ‘Chasing Cars’ move up another notch adding RECOMMENDED LISTENING drums and several distorted guitars playing different inversions (where the notes of a chord are arranged Snow Patrol’s songs are masterpieces of in a different order) to create an orchestra-like wall of arrangement and see the guitar adopting a supporting guitars. The end of the song sees the song return to role on their songs rather than the dominant riffs its sparse beginnings with the re-stating of the simple and extended guitar solos you might expect to hear picked guitar part. from a rock, blues or metal band. -

Magorův Zápisník Ivan Martin Jirous Znění Tohoto Textu Vychází Z Díla Magorův Zápisník Tak, Jak Bylo Vydáno Nakladatelstvím Torst V Praze V Roce 1997

Magorův zápisník Ivan Martin Jirous Znění tohoto textu vychází z díla Magorův zápisník tak, jak bylo vydáno nakladatelstvím Torst v Praze v roce 1997. Pro potřeby vydání Městské knihovny v Praze byl text redakčně zpracován. § Text díla (Ivan Martin Jirous: Magorův zápisník), publikovaného Městskou knihovnou v Praze, je vázán autorskými právy a jeho použití je definováno Autorským zákonem č. 121/2000 Sb. Vydání (obálka, upoutávka, citační stránka a grafická úprava), jehož autorem je Městská knihovna v Praze, podléhá licenci Creative Commons Uveďte autora-Nevyužívejte dílo komerčně-Zachovejte licenci 3.0 Česko. Verze 1.0 z 28. 2. 2020. OBSAH I . 8 Eva Fuková . 9 JaromírZ Funke . 11 Konstruktivní tendence. .13 ateliéru Dušana Kadlece. .16 Zemřel Lucio Fontana. .18 Otevřené možnosti. 24 Marcel Duchamp. 32 Pavel Laška. .34 Socha v plenéru. .36 Socha piešťanských parků 69. 44 Američané v Praze. 4955 ComicsI . 5552 3× Naděžda Plíšková. III. Grafika Naděždy Plíškové. .57 . 58 Beatles v obrazech. 60 Sochy pro budoucí město?. .62 Otakar Slavík Karel Nepraš. 68 Čas unáší Krásu Čas odhaluje Pravdu. 71 Několik pražských výstav . .75 Sporckův Kuks aneb Od minulosti k utopii. .81 Kamil Linhart . 90 Jan a Josef Wagnerovi. .92 Liběchov Václava Levého. 94 Konfrontace II . 97 Pocta Andy Warholovi. .99 Tato výstava . .109 Divnost, že vůbec jsme. .112 Zpráva o činnosti Křižovnické školy . 116 Eugen Brikcius. .125 Bude religiózní, nebo…. .129 II Fotografie Jana Šafránka . .133 Ach Nachtigal. 134 . .139 Mesaliance, či zásnuby mezi beatovou hudbou a výtvarným uměním? . .140 II. beatový festival. 145 SedmáI generace romantiků . 149 ZprávaII o třetím českém hudebním obrození. 158 III. 158 IV.