Tamil Language and Religion in Movies the Background and Process of Usage and Meaning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sacredkuralortam00tiruuoft Bw.Pdf

THE HERITAGE OF INDIA SERIES Planned by J. N. FARQUHAR, M.A., D.Litt. (Oxon.), D.D. (Aberdeen). Right Reverend V. S. AZARIAH, LL.D. (Cantab.), Bishop of Dornakal. E. C. BEWICK, M.A. (Cantab.) J. N. C. GANGULY. M.A. (Birmingham), {TheDarsan-Sastri. Already published The Heart of Buddhism. K. J. SAUNDERS, M.A., D.Litt. (Cantab.) A History of Kanarese Literature, 2nd ed. E. P. RICE, B.A. The Samkhya System, 2nd ed. A. BERRDZDALE KEITH, D.C.L., D.Litt. (Oxon.) As"oka, 3rd ed. JAMES M. MACPHAIL, M.A., M.D. Indian Painting, 2nd ed. Principal PERCY BROWN, Calcutta. Psalms of Maratha Saints. NICOL MACNICOL, M.A. D.Litt. A History of Hindi Literature. F. E. KEAY, M.A. D.Litt. The Karma-Mlmamsa. A. BERRIEDALE KEITH, D.C.L., D.Litt. (Oxon.) Hymns of the Tamil aivite Saints. F. KINGSBURY, B.A., and G. E. PHILLIPS, M.A. Hymns from the Rigveda. A. A. MACDONELL, M.A., Ph.D., Hon. LL.D. Gautama Buddha. K. J. SAUNDERS, M.A., D.Litt. (Cantab.) The Coins of India. C. J. BROWN, M.A. Poems by Indian Women. MRS. MACNICOL. Bengali Religious Lyrics, Sakta. EDWARD THOMPSON, M.A., and A. M. SPENCER, B.A. Classical Sanskrit Literature, 2nd ed. A. BERRIEDALE KEITH, D.C.L., D.Litt. (Oxon.). The Music of India. H. A. POPLEY, B.A. Telugu Literature. P. CHENCHIAH, M.L., and RAJA M. BHUJANGA RAO BAHADUR. Rabindranath Tagore, 2nd ed. EDWARD THOMPSON, M.A. Hymns of the Alvars. J. S. M. HOOPER, M.A. (Oxon.), Madras. -

Insight Gen. Studies &Csat

INSIGHT GEN. STUDIES &CSAT Under the Personal Guidance of S. BALIYAN SOUTH INDIAN HISTORY TOPIC - XVIII THE SANGAM AGE SANGAM AGE - LITERATURE ••• Sangam age is rightly regarded as constituting the Augustan age of Tamil literature. ••• It deals with secular matters relating to public and social activity like Government, war, charity, renunciation, worship, trade, and agriculture, physical manifestations of nature like mountains and rivers and private thoughts and activity like conjugal love and domestic life of the inner circle of the members of the family. ••• They are called Puram and Aham (Agam). Puram literature deals with matters capable of externalization or objectification. Aham literature deals with matters strictly limited to one aspect of subjective experience viz. love. The division of Aham and Puram is essentially Tamilian. ••• The Tamils were not strangers to other forms of classifying literary themes viz., Aram. Porul, Inbam and Vidu. These were four goals of life and the literature which deals with them falls under the corresponding sections. This classification is not much different from the Aham – Puram classification because Aram, Porul and Vidu come under Puram and Inbam under Aham. ••• Tolkappiyar, Valluvar, Iliango Adigal, Sittalai Sattanar, Nakkirar, Kapilar, Paranar, Auvaiyar, Mangudi Marudanar and a few others were outstanding the poets and thinkers of the Sangam age. ••• The Pattuppattu is a collection of ten long poems. Of these Mulaippattu, Kurinjipattu and Pattinappalai belong to Aham and the rest are Puram. ••• Some of the anthologies belong to Aham group and the others to Puram group. ••• The same is the case with the eighteen Killkkanakku works. ••• Nearly 75 small edicts have been found from caves near Madurai. -

FACULTY of ARTS, UNIVERSITY of JAFFNA Centre for Open and Distance Learning (CODL) BACHELOR of ARTS DEGREE PROGRAM

FACULTY OF ARTS, UNIVERSITY OF JAFFNA Centre for Open and Distance Learning (CODL) BACHELOR OF ARTS DEGREE PROGRAM Structure of the Degree programme 1.0 Introduction In accordance with the re-structuring of existing External Degree Program as per the Commission Circular no 932, Faculty of Arts, University of Jaffna, proposing a new structure, incorporating the provisions of the credit valued system. The new regulations shall be effective for the new entrants of the forthcoming academic year 2011/2012 onwards. 2.0 Structure of study program All study programs have designed to suit the semester based course unit system and Grade Point Average (GPA) evaluation and marking scheme. 2.1 Degrees The Faculty of Arts offers the following Degree programs. 2.1.1 B.A general Degree program of 03 years duration. (SLQF level – 05) 2.1.2 B.A special degree program of 04 years duration. (SLQF level – 06) The General Degree program offers a minimum of 90 credits, to be completed within a period of 03 years. (06 semesters of 20 weeks duration including examination period), with provision to extend up to a maximum of 06 years, depending on the students choice. The Special Degree program offers minimum of 120 credits, to be completed within a period of 04 years. (08 semesters of 20 week duration including examination period), with provision to extend maximum of 08 years, depending on the students choice. One credit is equivalent to 30 hours of contact hours (face to face instructions, tutorial, lab classes, if any, online or computer based learning, independent learning and examinations). -

Values in Leadership in the Tamil Tradition of Tirukkural Vs. Present-Day Leadership Theories

International Management Review Vol. 3 No. 1 2007 Values in Leadership in the Tamil Tradition of Tirukkural Vs. Present-day Leadership Theories Anand Amaladass Satya Nilayam Research Institute, Chennai, South India [Abstract] It is useful to keep in mind the present-day discussion on leadership theories from the Western traditions before looking at an ancient Indian text from a leadership perspective. The purpose is not to seek parallels, but to juxtapose them. In this way the reader will evocatively perceives the underlying value system found in the Indian text discussed here. Obviously, historical contexts and present day worldviews are different. But wisdom embedded in ancient Indian tradition has perennial values that transcends time and space; is applicable to every period of history and has cross-cultural appeal. The research shall briefly sum up what “leadership” means in today’s management sectors. The theme of the paper is ‘Values in Leadership.’ This presentation will be based on this ancient Tamil text Tirukkural, which discusses administration and management by a ruler in his country. [Keywords] Leadership; Tamil tradition; Tirukkural; administration; management; Indian ruler Introduction Western traditions concept of Leadership has a history of development (Bernard M. Bass). In the early days, prophets, priests, chiefs, and kings were models of leadership. The Greek concepts of leadership were illustrated by the heroes in Homer’s epic Iliad. The qualities admired by the Greeks are justice and judgment (Agamemnon), wisdom and council (Hector), shrewdness and cunning (Odysseus), valor and activism (Achilles). Philosophers like Plato looked for an ideal leader to rule the State with order and reason. -

English 710-882

AN ETHNOMUSICOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE ON KANIYAN KOOTHU Aaron J. Paige This paper will analyze some of the strategies by which Kaniyans, a minority com- munity from the Southern districts of Tamil Nadu, use music as a vehicle to negoti- ate, reconcile, and understand social, cultural, and economic change. Kaniyan Koothu performances are generally commissioned for kodai festivals, during which Kaniyans sing lengthy ballads. These stories vary locally from village to village and recount the adventures, exploits, and virtues of gods and goddesses specific to the area and community in which they are worshipped. While these narratives are en- tertaining in their own right, they also serve as springboards for subjective compari- son and interpretation. Kaniyans thus, transform mythological legends into modern social commentary. In a world perceived to be growing increasingly complicated by globalization and modernization, these folk musicians openly voice in performance both their concern for the loss of traditional values and their trepidation that Tamil culture, tamizh panpaadu – particularly village culture, gramiya panpaadu – are gradually being displaced by foreign principles, products, and technologies. In con- tradistinction to this conservative rhetoric, the Kaniyans, in recent years, have made major reformations to their own musical practice. Using specific textual examples, the first part of this paper will look at the ways in which musicians’ semi-improvised narratives foster solidarity under the rubric of a shared Tamil language and cultural identity. The second part of this paper, by way of musical examples, will attempt to illuminate how these same musicians are engaged in redefining and reformulating their musical tradition through the appropriation and integration of rhythmic models characteristic of Carnatic drumming. -

Inner Meaning of Human History.Pmd

THE INNER MEANING OF HUMAN HISTORY Collected works of Dr. Justice S. Maharajan Compiled and Published by: M.Chidambaram First Edition, 2012 © M.Chidambaram All Rights Reserved Price: Rs. 450 The cost of publishing this book is borne by the grand children of Justice. S.Maharajan. The proceeds from the sale of this book will go to charitable organizations. Cover Design: Ramkumar M Typeset by : Fairy Lass M Printed at : Books available at: Kalaignan Pathippagam 10, Kannadasan Salai, T.Nagar, Chennai 600 017 044-24345641 Published by : M.Chidambaram 31- Vijayaragava Road, T. Nagar, Chennai 600 017 E-mail: [email protected] CONTENT Foreword . 5 1. The Inner Meaning of Human History as Disclosing the One Increasing Purpose that runs through the Ages . 15 2. The Culture of Tamils . 51 3. Tiruvalluvar . 73 4. Kamban . 201 5. Tirumoolar and the Eighteen Siddhas . 327 6. Saint Arunagiri Nathar, The Mystic . 347 7. T.K.C. The Man of letters . 355 8. Rajaji’s Contribution to Tamil Prose . 361 9. Prof. A. Srinivasa Raghavan - as a Critic . 371 10. Thondaman – A Great Literary Force . 377 11. Some Problems of Shakespeare Translation into Tamil. 383 3 12. Some Problems of Law Translation into the Indian languages . 403 13. Administration of Franco- Indian Laws - Some Glimpses. 415 14. The English and the French Systems of Jurisprudence . 447 15. Address At The Conference Of District Judges and District Magistrates . 457 16. Reflections of a Retired Judge . 471 17. The High-Brow . 481 18. My experience in inter-faith dialogue . 489 19. The Gandhian Epic in Contemporary Society . -

Dr. Gloria V.Dhas

Dr. Gloria V.Dhas Head of the Department Department of Christian Tamil Studies Mobile No: 9865627359 School of Religions, Philosphy and Humanist Thought Email:[email protected] Educational Qualifications : M.A.,M.A., M.Ed., PG.Dip.Sikh., PG.Dip.Yoga.,M.Phil., Ph.D Professional Experience : 23 Year FIELD OF SPECIALIZATION . Literature . Comparative Religion . Ecology, Feminism and Dalit Philospy RESEARCH SPECIALIZATION . Tamil Literature . Social Changes through Religions . Transformation by Social Services Research Supervision: Program Completed Ongoing Ph.D 5 7 M.Phil 35 2 PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE No Institution Position From (date) To (date) Duration 1 Lady Doak College 23.11.1992 01.11.1993 One Year Lecturer 2 Lady Doak College 27.01.1994 16.04.1994 Three Lecturer MOnths 3 Avinasilingam 19.10.1994 15.05.1995 Eight Deemed Project Assistant Months University, Coimbator. 4 Madurai Kamaraj 18.05.1995 17.05.2000 Five University Research Associate Years Madurai - 21 5 Madurai Kamaraj 02.07.2000 30.04.2001 Ten University Teaching Assistant Months Madurai - 21 6 School of 02.07.2001 30.04.2002 Ten Religions, Teaching Assistant Months Philosophy & Humanist Thought 7 School of 02.07.2002 14.10.2010 Eight Religions, Guest Lecturer Years Philosophy & Humanist Thought 8 and Head in charge Madurai Kamaraj Assistant Professor 15.03.2010 Till Date Till Date University Madurai- COMPLETED RESEARCH PROJECT No Title of the Project Funding Agency Total Grant Year 1 God Concept in CICT 2,50,000 2013‐2014 Sangam Literature HONORS/AWARDS/RECOGNITIONS . Honour Award in Lady Dock College - 1983 . Best Teacher Award in Madurai Kamaraj University - 2017 PAPER PRESENTED IN CONFERENCE/SEMINAR/WORKSHOP International Papers S.No Year Seminars 1 2015 Tradition and culture in ancient tamils, International Seminar on Katralum Karpithalum, conduted by Ministry of Singapore, and Lady Doak College, 2 2015 Madurai in Tamil Literature,Christianity in Madurai, Arulmegu Meenakshi Women’s College, Madurai. -

Tiruvalluvar.Pdf

9 788126 053216 9 788126 053216 TIRUVALLUVAR The sculpture reproduced on the end paper depicts a scene where three soothsayers are interpreting to King Śuddhodana the dream of Queen Māyā, mother of Lord Buddha. Below them is seated a scribe recording the interpretation. This is perhaps the earliest available pictorial record of the art of writing in India. From: Nagarjunakonda, 2nd century A.D. Courtesy: National Museum, New Delhi MAKERS OF INDIAN LITERATURE TIRUVALLUVAR by S. Maharajan Sahitya Akademi Tiruvalluvar: A monograph in English on Tiruvalluvar, eminent Indian philosopher and poet by S. Maharajan, Sahitya Akademi, New Delhi: 2017, ` 50. Sahitya Akademi Head Office Rabindra Bhavan, 35, Ferozeshah Road, New Delhi 110 001 Website: http://www.sahitya-akademi.gov.in Sales Office ‘Swati’, Mandir Marg, New Delhi 110 001 E-mail: [email protected] Regional Offices 172, Mumbai Marathi Grantha Sangrahalaya Marg, Dadar Mumbai 400 014 Central College Campus, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar Veedhi Bengaluru 560 001 4, D.L. Khan Road, Kolkata 700 025 Chennai Office Main Guna Building Complex (second floor), 443, (304) Anna Salai, Teynampet, Chennai 600 018 First Published: 1979 Second Edition: 1982 Reprint: 2017 © Sahitya Akademi ISBN: 978-81-260-5321-6 Rs. 50 Printed by Sita Fine Arts Pvt. Ltd., A-16, Naraina Industrial Area Phase-II, New Delhi 110028 CONTENTS Introduction 7 The Times and Teachings of Tiruvalluvar 11 Translations and Citations 19 The Personality of Tiruvalluvar 25 Interpretation of the Kural 33 Word-worship 37 Sensual Love 41 Architectonics of the Kural 47 Some Glimpses of Tiruvalluvar 54 Valluvar at the World Vegetarian Congress 71 Valluvar’s Blue Print for the Evolution of Man 73 The Bard of Universal Man 98 APPENDIX Transliteration of Tamil words with diacritical marks 105 Bibliography 106 1 INTRODUCTION Though Tiruvalluvar lived about 2000 years ago, it does not seem he is dead. -

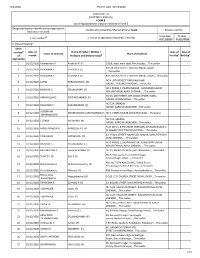

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V, PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applica Ons For

12/2/2020 Form9_AC6_02/12/2020 ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V, PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applicaons for inclusion received in Form 6 Designated locaon identy (where applicaons Constuency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): Avadi Revision identy have been received) From date To date @ 2. Period of applicaons (covered in this list) 1. List number 01/12/2020 01/12/2020 3. Place of hearing* Serial $ Date of Name of Father / Mother / Date of Time of number Name of claimant Place of residence of receipt Husband and (Relaonship)# hearing* hearing* applicaon 1 01/12/2020 Manikandan K Krishnan R (F) 135/8, avadi main road, Paruthipau, , Thiruvallur #20, BOUND STREET, KOVILPATHAGAI, AVADI 2 01/12/2020 PRASANNA E ELANGO R (F) , , Thiruvallur 3 01/12/2020 PRASANNA E ELANGO R (F) #20, BOUND STREET, KOVILPATHAGAI, AVADI, , Thiruvallur NO 6 , 8TH STREET THIRUVALLUVAR 4 01/12/2020 LATHA PARAMASIVAM (H) NAGAR, THIRUMULLAIVOYAL, , Thiruvallur NO 5 PHASE 1, SWATHI NAGAR , KANNADAPALAYAM 5 01/12/2020 BHAVANI S SELVAKUMAR (F) KOVILPATHAGAI AVADI CHENNAI , , Thiruvallur NO 26, 2ND STREET, 4TH CROSS STREET, INDRA 6 01/12/2020 AMANULLAH S SYED MOHAMED (F) NAGAR, CHOLAPURAM, , Thiruvallur NO 72A, SARADHI 7 01/12/2020 RAJAMANI C EAKAMBARAM (F) NAGAR, KARUNAKARACHERI, , Thiruvallur SUBISHANA 8 01/12/2020 DHARMAGURU LAKSHMANAN (F) NO 1, INDRA NAGAR, KOVILPADHAGAI, , Thiruvallur DHARMAGURU NO 72A, SARATHI 9 01/12/2020 C GIRIJA RAJAMANI (H) NAGAR, KARUNAKARACHERI, , Thiruvallur PLOT NO 91, 6 TH STREET THIRUMALAI VASAN NAGAR S 10 01/12/2020 MANU RAMESH R RAMESAN P G (F) M NAGAR POST, -

A Primer of Tamil Literature

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com A PRIMER OF TAMIL LITERATURE BY iA. S. PURNALINGAM PILLAI, b.a., Professor of English, St. Michael's College, Coimbatore. PRINTED AT THE ANANDA PRESS. 1904. Price One Rupee or Two Shillings. (RECAP) .OS FOREWORD. The major portion of this Primer was written at Kttaiyapuram in 1892, and the whole has lain till now in manuscript needing my revision and retouching. Owing to pressure of work in Madras, I could spare no time for it, and the first four years of my service at Coim- batore were so fully taken up with my college work that I had hardly breathing time for any literary pursuit. The untimely death of Mr. V. G. Suryanarayana Sastriar, B.A., — my dear friend and fellow-editor of J nana Bodhini — warned me against further delay, and the Primer in its present form is the result of it. The Age of the Sangams was mainly rewritten, while the other Ages were merely touched up. In the absence of historical dates — for which we must wait, how long we do not know — I have tried my best with the help of the researches already made to divide, though roughly, twenty centuries of Tamil Literature into Six Ages, each Age being distinguished by some great movement, literary or religious. However .defective it may be in point of chronology, the Primer will justify its existence if it gives foreigners and our young men in the College classes whose mother-tongue is Tamil, an idea of the world of Tamil books we have despite the ravages of time and white-ants, flood and fire, foreign malignity and native lethargy. -

Daniel Poor Memorial Library

Daniel Poor Memorial Library The American College, Madurai www.americancollege.edu.in Sponsored By: United Board, USA Digitized Books List SN Acc No Title Year Pages 1 8623 Pallava Antiquities vol.2 1918 40 2 8333 Natural Religion in India 1891 65 3 6062 A Birds-eye view of the origin and destiny 1911 181 4 7484 Hampi Ruins 1917 157 5 5959 A Guide of British 1912 189 6 8861 The Yogasara Sangraha 1894 173 7 20110 Economic Studies Vol.1 1918 303 8 17067 The Sciences of the Sulba 1932 267 9 3072 Life of Christ 1884 431 10 23275 Life Beyond Death 1944 303 11 18373 History of Math Notations 1921 367 12 12693 Tale of Tulsi plant 1916 177 13 12836 Historical Atlas 1927 96 14 7274 The Book of Ser Marco Polo1 1903 661 15 6716 The works of Thomas Dicks 1851 666 16 1453 Science of politics 1887 204 17 7564 Asian Athenths 1873 553 18 8992 Indian game birds 1921 328 19 35438 Thirukural Aaivu 1963 1020 20 2020 History of England vol 4 1856 750 21 9874 Coins of the Indian Museum 1895 288 22 7509 Progress of Education in India 1912 -1917 1918 215 23 7232 Buddhist record of Western India 1906 369 24 7644 Elizabethan Drama 1558 – 1642 1910 685 25 2017 History of England Vol-1 1849 619 26 22101 The Script of Harappa 1934 210 1 Daniel Poor Memorial Library The American College, Madurai www.americancollege.edu.in Sponsored By: United Board, USA Digitized Books List SN Acc No Title Year Pages 27 9024 On the Art of Writing 1921 251 28 2019 History of England Vol.3 1856 686 29 14056 Thembaavani 1927 415 30 4213 German Language 1842 452 31 9869 Ancient Coins -

Programme Outcomes

MUTHURANGAM GOVT. ARTS COLLEGE (A), VELLORE – 02 DEPARTMENT OF TAMIL PROGRAMME : FOUNDATION TAMIL, NON – MAJOR, B.A. MAJOR TAMIL Programme Outcomes PO – 1. Modern literature: ( Poetry - Prose - Non - detailed) These subjects are helping students to become a creative writers, essay writers, orators, actors, stage performers etc., to secure good fame and name in the society. PO – 2. Grammar: (nannool - yaapu - thandi - puraporul venbmaalai - nambi agapporul - dravida mozhigalin oppilakanam) The grammar subject is playing key role in the language syllabus. This subject is helping them to learn the language fluently to read write and speak. Tamil grammar is most important to sustain the standard of the language. PO _ 3. Inscription and archaeology: These are the allied subjects & Non major subjects which is closely related to the Tamil language and literature since from the ancient period. These subjects brings knowledge on the history and growth of Tamil language and literature as well as the culture of the Tamils. Programme specific Outcomes Pso – 1. Journalism and mass communication: This subject helps students to get job opportunities in the competitive society. Today mass media and communication is very familiar to accommodate skilled persons to run the departments well. In fact, Tamil learned graduates were giving first priority. PsO – 2. Tourism management: This subject also helps students to learn more about tourism places and its importance. This subject leads them to become a self employed person in various directions. PsO – 3. Folklore - feminism: These subjects also teaches the students about trends of the modern social changes and make them aware to build this equilibrium in the society.