JRRP2018 Kelly Guccione.Pdf (781.7Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atheneum Nantucket Dance Festival

NANTUCKET ATHENEUM DANCE FESTIVAL 2011 Featuring stars of New York City Ballet & Paris Opera Ballet Benjamin Millepied Artistic Director Dorothée Gilbert Teresa Reichlen Amar Ramasar Sterling Hyltin Tyler Angle Daniel Ulbricht Maria Kowroski Alessio Carbone Ana Sofia Scheller Sean Suozzi Chase Finlay Georgina Pazcoguin Ashley Laracey Justin Peck Troy Schumacher Musicians Cenovia Cummins Katy Luo Gillian Gallagher Naho Tsutsui Parrini Maria Bella Jeffers Brooke Quiggins Saulnier Cover: Photo of Benjamin Millepied by Paul Kolnik 1 Welcometo the Nantucket Atheneum Dance Festival! For 177 years the Nantucket Atheneum has enriched our island community through top quality library services and programs. This year the library served more than 200,000 adults, teens and children year round with free access to over 1.4 million books, CDs, and DVDs, reference and information services and a wide range of cultural and educational programs. In keeping with its long-standing tradition of educational and cultural programming, the Nantucket Atheneum is very excited to present a multifaceted dance experience on Nantucket for the fourth straight summer. This year’s performances feature the world’s best dancers from New York City Ballet and Paris Opera Ballet under the brilliant artistic direction of Benjamin Millepied. In addition to live music for two of the pieces in the program, this year’s program includes an exciting world premier by Justin Peck of the New York City Ballet. The festival this week has offered a sparkling array of free community events including two dance-related book author/illustrator talks, Frederick Wiseman’s film La Danse, Children’s Workshop, Lecture Demonstration and two youth master dance classes. -

DHS at Odds Withdep Tersection

NON PROFIT ORG. U.S. Postage Paid Darien, Conn. Permit No. 43 Darien High School 80High School Lane Darien, CT 06820 Courts: Students cannot grade other students' papers .ByMike Sullivan Rights and Privacy Act, when they al rights to a student, which allows the stu all federal funding to an institution, News Editor lowed other students to grade her dent to see his or her educational which violates FERPA. These harsh pen Privacy in our classrooms is some children's assignments. Ms. Falvo filed records, seek amendment to those alties associated with FERPA are why thing that students take for granted a class-action lawsuit against the school records, the right to consent disclosure the ruling is such a landmark decision. these days. Many of us don't think district in October of 1998. The lawsuit ofhis or her records, and the right to file The problem for some people is that about it when peers edit or grade our was turned down on both counts in 1998, a compliant with the Department ofEdu the decision is too broad and affects too papers. Many of us share our grades in however the Court of Appeals over cation. In short, it means that the educa many aspects of school life, such as the hallways, in attempts to determine our turned the lower courts' decision on the tional records of a student must be kept posting of honor rolls, and displays of how we rank in our group of friends. second count of the case. As the Court confidential. Although this law has been student work in hallways. -

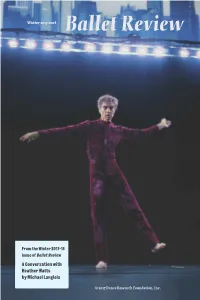

Michael Langlois

Winter 2 017-2018 B allet Review From the Winter 2017-1 8 issue of Ballet Review A Conversation with Heather Watts by Michael Langlois © 2017 Dance Research Foundation, Inc. 4 New York – Elizabeth McPherson 6 Washington, D.C. – Jay Rogoff 7 Miami – Michael Langlois 8 Toronto – Gary Smith 9 New York – Karen Greenspan 11 Paris – Vincent Le Baron 12 New York – Susanna Sloat 13 San Francisco – Rachel Howard 15 Hong Kong – Kevin Ng 17 New York – Karen Greenspan 19 Havana – Susanna Sloat 46 20 Paris – Vincent Le Baron 22 Jacob’s Pillow – Jay Rogoff 24 Letter to the Editor Ballet Review 45.4 Winter 2017-2018 Lauren Grant 25 Mark Morris: Student Editor and Designer: Marvin Hoshino and Teacher Managing Editor: Joel Lobenthal Roberta Hellman 28 Baranovsky’s Opus Senior Editor: Don Daniels 41 Karen Greenspan Associate Editors: 34 Two English Operas Joel Lobenthal Larry Kaplan Claudia Roth Pierpont Alice Helpern 39 Agon at Sixty Webmaster: Joseph Houseal David S. Weiss 41 Hong Kong Identity Crisis Copy Editor: Naomi Mindlin Michael Langlois Photographers: 46 A Conversation with Tom Brazil 25 Heather Watts Costas Associates: Joseph Houseal Peter Anastos 58 Merce Cunningham: Robert Gres kovic Common Time George Jackson Elizabeth Kendall Daniel Jacobson Paul Parish 70 At New York City Ballet Nancy Reynolds James Sutton Francis Mason David Vaughan Edward Willinger 22 86 Jane Dudley on Graham Sarah C. Woodcock 89 London Reporter – Clement Crisp 94 Music on Disc – George Dorris Cover photograph by Tom Brazil: Merce Cunningham in Grand Central Dances, Dancing in the Streets, Grand Central Terminal, NYC, October 9-10, 1987. -

NEW YORK CITY BALLET DIGITAL SPRING SEASON | APRIL 20 – JUNE 1, 2020 Nycballet.Com/Digitalspring

NEW YORK CITY BALLET DIGITAL SPRING SEASON | APRIL 20 – JUNE 1, 2020 nycballet.com/digitalspring WEEK 6: Monday, May 25 – Monday, June 1 Monday, May 25: City Ballet The Podcast “New Combinations” episode, featuring interviews with NYCB Resident Choreographer Justin Peck (recorded in 2017 about The Times Are Racing) and choreographer Pam Tanowitz (recorded in 2019 about Bartók Ballet), hosted by Wendy Whelan, NYCB Associate Artistic Director (available at podcast.nycballet.com, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, Luminary, the iHeartRadio app, and other podcast platforms) Ballet Essentials – Stars and Stripes 45-minute interactive movement workshop suitable for people of all ages and level of training consisting of a ballet warm-up and a movement combination inspired by George Balanchine’s Stars and Stripes, taught by NYCB Soloist Indiana Woodward (register at balletessentials.nycballet.com; workshop at 6pm EDT) Tuesday, May 26: NYCB Performance Donizetti Variations Music by Gaetano Donizetti Choreography by George Balanchine PRINCIPAL CASTING: Ashley Bouder and Andrew Veyette with the NYCB Orchestra conducted by Daniel Capps, NYCB Resident Conductor Filmed on January 28, 2015, David H. Koch Theater, Lincoln Center Introduction by Kay Mazzo, former NYCB Principal Dancer and School of American Ballet Chairman of Faculty (available at nycballet.com, facebook.com/nycballet, and youtube.com/nycballet from Tuesday, May 26 at 8pm until Friday, May 29, at 8pm EDT) Wednesday, May 27: Wednesday with Wendy Live ballet-inspired movement class suitable -

New York City Ballet Moves Odc/Dance Malpaso Dance Company

2017 // 18 SEASON FALL PROGAM MALPASO DANCE COMPANY with special guest Zenon Dance Company Tue, Oct 10 Coming Home Indomitable Waltz Ocaso Why You Follow NEW YORK CITY BALLET MOVES Sat, Oct 28 In the Night La Stravaganza Sonatine After the Rain pas de deux In Creases ODC/DANCE Thu, Nov 2 boulders and bones Presents WELCOME to the Northrop Dance fall season performances! ODC will wrap up the Fall Series with a special event for families and children—their holiday classic, The Velveteen Rabbit. It’s a beautiful story about love and the things that really matter, and a great beginning Fall is a beautiful time of year here in Minnesota, with to the holiday season. gorgeous autumn colors drawing us outdoors. But, as the days get shorter and the air gets crisper and colder, Twin When artists are doing the kind of fascinating work described above, don’t you just want to learn more Cities arts organizations present a cornucopia full of about them, and hear more about the inspiration that ignites these projects? I certainly do! That’s why I exciting events, enticing us all to come inside and share the am pleased to continue the performance previews—still FREE to all Northrop ticket holders—in the Best communal experience of live performances. Buy Theater, one hour and 15 minutes before curtain. I hope you’ll join me there to meet some of the artists, and ask questions about the work you are about to experience. I am pleased and grateful that you have chosen Northrop as one of your gathering places and that you are part And if you want to learn even more, and have a great time as well, join us for any and all of the films of a community that celebrates dance. -

Choreographer Oona Doherty on Dancing Into Motherhood | Financial Times

4/1/2021 Choreographer Oona Doherty on dancing into motherhood | Financial Times Dance Choreographer Oona Doherty on dancing into motherhood A new generation of dancers are bringing their pregnancies into performances Laura Cappelle 9 HOURS AGO Pregnant or not, the Northern Irish choreographer Oona Doherty isn’t one to sway gently under soft lighting. In The Devil, a dance film she made with Luca Truffarelli for New York’s Irish Arts Center, she gets chased, killed and tied up — before emerging naked from a literal bloodbath. “I was trying to figure out how to do a pregnancy dance film that’s not cliché, and I just had this taste for blood,” Doherty says over Zoom from her home in Bangor, near Belfast. She was eight months pregnant when she filmed The Devil; now, her nine- week-old daughter Rosaria is in the next room. The plain-spoken 35-year-old may be one of the few dancer-choreographers to have relished the pandemic. Doherty has been in high demand since the success of 2017’s Hard to Be Soft: A Belfast Prayer and The Ascension Into Lazarus, both visceral explorations of working-class masculinity (and femininity, too). Yet life on tour proved lonely. “I started to have a little bit of a nervous breakdown,” she says. “I needed a break.” https://www.ft.com/content/c43c420e-501f-400e-9a81-f444b1b9d86d 1/8 4/1/2021 Choreographer Oona Doherty on dancing into motherhood | Financial Times Oona Doherty performing last year © Jane Hobson/Shutterstock Doherty got her wish, and then some. Described by her as a “transition film”, The Devil is a still-rare example of a visibly pregnant performer in the spotlight. -

Restless Creature: Wendy Whelan

Presents RESTLESS CREATURE: WENDY WHELAN 2016 - USA - 90 MINUTES - IN ENGLISH A FILM BY LINDA SAFFIRE, ADAM SCHLESINGER Distributed in Canada by Films We Like Bookings and General Inquries: mike@filmswelike.com Publicity and Media: mallory@filmswelike.com SYNOPSIS RESTLESS CREATURE: WENDY WHELAN offers an intimate portrait of prima ballerina Wendy Whelan as she prepares to leave New York City Ballet after a record-setting three decades with the company. One of the modern era’s most acclaimed dancers, Whelan was a principal ballerina for NYCB and, over the course of her celebrated career, danced numerous ballets by George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins, as well as new works by more modern standout choreographers like Christopher Wheeldon and Alexei Ratmansky; many roles were made specifically for Whelan. As the film opens, Whelan is 46, battling a painful injury that has kept her from the ballet stage, and facing the prospect of her impending retirement from the company. What we see, as we journey with her, is a woman of tremendous strength, resilience and good humor. We watch Whelan brave the surgery that she hopes will enable her comeback to NYCB and we watch her begin to explore the world of contemporary dance, as she steps outside the traditionally patriarchal world of ballet to create Restless Creature, a collection of four contemporary vignettes forged in collaboration with four young choreographers. Throughout Linda Saffire and Adam Schlesinger’s riveting documentary, we watch Whelan grapple with questions of her own identity and worth. Historical footage shows her dancing as a very young girl in her hometown of Louisville, Kentucky, then as a teenager on her own in New York and, finally, as a rising ballerina with the company. -

THE PATIENT IS BREATHING Again

162 DANCING chine’s style, and also his last wife, and the honoree of the festival’s opening night, and, not incidentally, the holder of the American rights to most of his repertory, on which N.Y.C.B. depends. The video was thrilling. Even if you knew it (it’s famous), it gave you chills THE PATIENT IS BREATHING again. Le Clercq stood at arm’s length from her partner (Jacques d’Amboise), Signs of life at New York City Ballet. and pirouetted, now inward, now out- BY JOAN ACOCELLA ward, against him. Her movement had a whiplike momentum: this was some- thing private, something understood be- “ HE audience is changed,” the among the new patrons, trying to see tween them. Yet, again and again, as she New York City Ballet dancer what they saw. Of course, I also saw turned to face us, she opened her arms to T Darci Kistler said to the Times what I saw—turns bobbled, details lost. us, gathering us into the event. There it a few years ago. “I don’t know what Still, you can’t lose the whole ballet. In was, the Balanchine style: objective—no happened.” I know what happened. “Agon,” the lead woman whipping her dramatics—and yet piercing. The film George Balanchine, who founded the leg around her partner’s neck, simulta- having been shown, the curtain was company, with Lincoln Kirstein, and cre- neously embracing and garroting him; raised, and Yvonne Borree, one of the ated its style and its repertory, died in in “Symphony in Three Movements,” company’s young principal dancers, 1983. -

DANCE for a CITY: FIFTY YEARS of the NEW YORK CITY BALLET New-York Historical Society Exhibition Curated by Lynn Garafola April 20 - August 15, 1999

DANCE FOR A CITY: FIFTY YEARS OF THE NEW YORK CITY BALLET New-York Historical Society Exhibition Curated by Lynn Garafola April 20 - August 15, 1999 The labels, wall texts, and reflections complement the volume Dance for a City: Fifty Years of the New York City Ballet published by Columbia University Press in 1999. Edited by Lynn Garafola, with Eric Foner, and including essays by Thomas Bender, Sally Banes, Charles M. Joseph, Richard Sennett, Jonathan Weinberg, and Nancy Reynolds, the book, unlike most exhibition catalogues, does not include a checklist. In revisiting this material, I wanted to evoke the experience of walking through six large galleries on the ground floor of the New-York Historical Society, with the reader enjoying by suggestion and as an act of imagination the numerous objects on display tracing the long history of the New York City Ballet. As I prepare this for publication on the Columbia University Academic Commons nearly two decades after the exhibition was dismantled, I thank once again the many lenders who made it possible. I also remain deeply grateful to the exhibition designer, Stephen Saitas, for his guidance and for creating an installation of haunting beauty.—Lynn Garafola Introductory Text Founded in 1948 by George Balanchine and Lincoln Kirstein, the New York City Ballet is universally recognized as one of the world's outstanding dance companies. This exhibition traces its development both as an artistic and social entity. The story begins with the fateful encounter of the two men in 1933, when Kirstein, an arts maverick and patron extraordinaire, invited the twenty-nine-year-old Russian-born choreographer to establish a company and a school in the United States. -

Orchestra Magazin Broj 45/50

y g y Br. 45 / 50 OrchestraDANCE MAGAZINE ČASOPIS ZA UMETNIČKU IGRU besplatan primerak / Free Copy Orchestra plus - Konci vremena Umetnička igra u Srbiji - putokaz istraživačima Milica Zajcev + Orchestra plus Plesna scena u Njujorku Marija Krtolica Poštovani čitaoci, Još jedna tema često me je naterivala na razmišljanje – poli- prošlo je više od godinu i po dana od poslednjeg izdanja tički korektan govor prema predloženom kodeksu neseksističke časopisa Orchestra. Različiti društveni, ekonomski, socijalni i upotrebe jezika (2004), preciznije predlog medijima da koriste lični razlozi osnivača uspeli su da tokom ovog perioda zakoče forme ženskog roda za profesije i titule, odnosno, kada su tzv. Orchestru koja se pre četrnaest godina drsko pojavila u javnosti ženske reči na prepad osvojile srpski jezik i počele da nas forsi- kao prvi i još uvek jedini stručno – informativni i edukativ- raju da za sve profesije, pošto poto, pronađemo oblik ženskog ni časopis posvećen isključivo svetu umetničke igre, kada je roda jer jedino tada iskazujemo poštovanje prema liku i delu Orchestra i postala član porodice koja čini srpsku kulturnu peri- neke ženske osobe. Činjenica je da se u ženski rod mogu sasvim odiku. Kreativni napori građanina, osnivača časopisa, ali i izvan- lako prevesti nazivi brojnih profesija, pogotovo u umetničkoj redno, dugogodišnje ulaganje intelektualne svojine u Orchestru igri, ali problem nastaje kada se rogobatnim i za govor teško svih njenih saradnika iz zemlje i sveta u ovom periodu konačno razumljivim i izgovorljivim ženskim rodom neke profesije ozbilj- su potpuno zanemareni, zatim uporno prećutkivani i, najzad, no ruži lepota i pravopis srpskog jezika. Dakle, može koreograf- s velikim uspehom zaboravljeni. -

City Ballet's Beauty

Spring 2013 Ball et Review From the Spring 2013 issue of Ballet Review The Sleeping Beauty at NYCB On the Cover: National Ballet of Cuba’s Viengsay Valdés in Peter Quanz’s Double Bounce 4 Jacob’s Pillow – Christine Temin 7 London – Jay Rogoff 8 Brooklyn, NY – Sandra Genter 9 New York – Joseph Houseal 11 Stuttgart – Gary Smith 12 New York – Sophie Flack 15 Basel – Renée E. D’Aoust 16 Hong Kong – Kevin Ng 17 London – Leigh Witchel 21 New York – Jay Rogoff 64 Larry Kaplan 24 Maria Tallchief: A Personal Recollection 27 Maria Tallchief (1925-201 3) Hugo von Hofmannstahl 50 Two Essays on Dance 27 Francis Mason Ballet Review 41.1 55 James Nomikos on Graham Spring 2013 Editor and Designer: Harris Green Marvin Hoshino 58 City Ballet’s Beauty Managing Editor: Roberta Hellman Sandra Genter Senior Editor: 64 Trisha Brown Don Daniels Associate Editor: Joel Lobenthal Gary Smith 58 69 Grand Theater Associate Editor: Larry Kaplan Ilona Landgraf Copy Editor: Barbara Palfy 74 Buckle’s Nijinsky Photographers: Tom Brazil 81 London Reporter – Clement Crisp Costas 92 Hanya Holm – George Jackson Associates: 93 Music on Disc – George Dorris Peter Anastos 100 Check It Out Robert Greskovic George Jackson Elizabeth Kendall 69 Paul Parish Nancy Reynolds James Su:on David Vaughan Edward Willinger Cover Photograph by Linda Reyes, National Ballet of Cuba: Sarah C. Woodcock Viengsay Valdés in Peter Quanz’s Double Bounce . Tiler Peck as Aurora. (Photo: Paul Kolnik, NYCB) 58 City Ballet’s Beauty because Diaghilev’s lavish 121 production for London had been the great impresario’s most spectacular flop. -

July 23–28, 2012

33481 Nan Ath CVR_Layout 1 7/16/12 11:44 AM Page 2 July 23–28, 2012 Benjamin Millepied Artistic Director Friday, July 27th at 6:30 p.m. Saturday, July 28th at 6:30 p.m. Nantucket High School Mary P. Walker Auditorium 33481 Nan Ath CVR_Layout 1 7/16/12 11:44 AM Page 3 DANCE FESTIVAL COMMITTEE 2012 Jane A. Tyler Marcia P. Welch Dance Festival Co-Chairs Marion Martin, Honorary Chair Susan Ambrecht Kathleen Hay Samantha Sandler Mary Randolph Ballinger Kathryn Kay Denise Saul Maureen Bousa Barbara E. Jones Audrey K. Schuster Roxanne Casscells Orla Murphy-LaScola Randee Seiger Jeanne Cohane Curtis Livingston Catharine Soros Barbara G. Cohen John W. Loose Maria Spears Patti Deuster Judy Goyette MacLeod Esta-Lee Stone John Falk Bonnie F. McCausland Pamela Thomas Barbara J. Fife Mary Jane McLean Phoebe Tudor Al Forster Patricia Moran Cathy Weinroth Cosby George Jeanne C. Miller Mary Wolff Tim George Penny Nieroth Marcella Zimmerman Nan Geschke A. Steven Perelman Suzy Grote Gleaves Rhodes NANTUCKET ATHENEUM BOARDOF TRUSTEES Alice F. Emerson William G. Spears Chair Vice-Chair Marcia P. Welch Alan M. Forster Secretary Treasurer Susan Boardman Kathryn Kay David Ross William J. Charlton Jeanne Casey Miller Bernard L. Swain Barbara J. Fife Orla Murphy-LaScola Jane A. Tyler Timothy M. George Pamela J. Nieroth Jay M. Wilson Robert A. Greenspon A. Steven Perelman Ronald Winters William E. Hannum III Anne Phaneuf P. Rhoads Zimmerman Barbara Jones Chairman Emeritus Trustees Emeriti Executive Director John W. Loose Nan Geschke Molly C. Anderson Martha Groetzinger President Emeritus Nancy A.