The Balanchine Dilemma: “So-Called Abstraction” and the Rhetoric of Circumvention in Black-And-White Ballets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charles M. Joseph. 2011. Stravinsky's Ballets. New Haven: Yale University

Charles M. Joseph. 2011. Stravinsky’s Ballets. New Haven: Yale University Press. Reviewed by Maeve Sterbenz Charles M. Joseph’s recent monograph explores an important subset of Stravinsky’s complete oeuvre, namely his works for dance. One of the aims of the book is to stress the importance of dance for Stravinsky throughout his career as a source of inspiration that at times significantly shaped his develop- ment as a composer. Joseph offers richly contextualized and detailed pictures of Stravinsky’s ballets, ones that will be extremely useful for both dance and music scholars. While he isolates each work, several themes run through Joseph’s text. Among the most important are Stravinsky’s self–positioning as simultaneously Russian and cosmopolitan; and Stravinsky’s successes in collaboration, through which he was able to create fully integrated ballets that elevated music’s traditionally subservient role in relation to choreography. To begin, Joseph introduces his motivation for the project, arguing for the necessity of an in–depth study of Stravinsky’s works for dance in light of the fact that they comprise a significant fraction of the composer’s output (more so than any other Western classical composer) and that these works, most notably The Rite of Spring, occupy such a prominent place in the Western canon. According to Joseph, owing to Stravinsky’s sensitivity to the “complexly subtle counterpoint between ballet’s interlocking elements” (xv), the ballets stand out in the genre for their highly interdisciplinary nature. In the chapters that follow, Joseph examines each of the ballets, focusing alternately on details of the works, histories of their production and reception, and their biographical contexts. -

Singapore Dance Theatre Launches 25 Season with Coppélia

ARTISTIC DIRECTOR | JANEK SCHERGEN FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MEDIA CONTACT Melissa Tan Publicity and Advertising Executive [email protected] Joseph See Acting Marketing Manager [email protected] Office: (65) 6338 0611 Fax: (65) 6338 9748 www.singaporedancetheatre.com Singapore Dance Theatre Launches 25th Season with Coppélia 14 - 17 March 2013 at the Esplanade Theatre As Singapore Dance Theatre (SDT) celebrates its 25th Silver Anniversary, the Company is proud to open its 2013 season with one of the most well-loved comedy ballets, Coppélia – The Girl with Enamel Eyes. From 14 – 17 March at the Esplanade Theatre, SDT will mesmerise audiences with this charming and sentimental tale of adventure, mistaken identity and a beautiful life-sized doll. A new staging by Artistic Director Janek Schergen, featuring original choreography by Arthur Saint-Leon, Coppélia is set to a ballet libretto by Charles Nuittier, with music by Léo Delibes. Based on a story by E.T.A. Hoffman, this three-act ballet tells the light-hearted story of the mysterious Dr Coppélius who owns a beautiful life-sized puppet, Coppélia. A village youth named Franz, betrothed to the beautiful Swanilda becomes infatuated with Coppélia, not knowing that she just a doll. The magic and fun begins when Coppélia springs to life! Coppélia is one of the most performed and favourite full-length classical ballets from SDT’s repertoire. This colourful ballet was first performed by SDT in 1995 with staging by Colin Peasley of The Australian Ballet. Following this, the production was revived again in 1997, 2001 and 2007. This year, Artistic Director Janek Schergen will be bringing this ballet back to life with a new staging. -

The Caramel Variations by Ian Spencer Bell from Ballet Review Spring 2012 Cover Photograph by Stephanie Berger, BAM : Silas Riener in Merce Cunningham’S Split Sides

Spring 2012 Ball et Review The Caramel Variations by Ian Spencer Bell from Ballet Review Spring 2012 Cover Photograph by Stephanie Berger, BAM : Silas Riener in Merce Cunningham’s Split Sides . © 2012 Dance Research Foundation, Inc. All rights reserved. 4 Moscow – Clement Crisp 5 Chicago – Joseph Houseal 6 Oslo – Peter Sparling 9 Washington, D. C. – George Jackson 10 Boston – Jeffrey Gantz 12 Toronto – Gary Smith 13 Ann Arbor – Peter Sparling 16 Toronto – Gary Smith 17 New York – George Jackson Ian Spencer Bell 31 18 The Caramel Variations Darrell Wilkins 31 Malakhov’s La Péri Francis Mason 38 Armgard von Bardeleben on Graham Don Daniels 41 The Iron Shoe Joel Lobenthal 64 46 A Conversation with Nicolai Hansen Ballet Review 40.1 Leigh Witchel Spring 2012 51 A Parisian Spring Editor and Designer: Marvin Hoshino Francis Mason Managing Editor: 55 Erick Hawkins on Graham Roberta Hellman Joseph Houseal Senior Editor: 59 The Ecstatic Flight of Lin Hwa-min Don Daniels Associate Editor: Emily Hite Joel Lobenthal 64 Yvonne Mounsey: Encounters with Mr B 46 Associate Editor: Nicole Dekle Collins Larry Kaplan 71 Psyché and Phèdre Copy Editor: Barbara Palfy Sandra Genter Photographers: 74 Next Wave Tom Brazil Costas 82 London Reporter – Clement Crisp 89 More Balanchine Variations – Jay Rogoff Associates: Peter Anastos 90 Pina – Jeffrey Gantz Robert Gres kovic 92 Body of a Dancer – Jay Rogoff George Jackson 93 Music on Disc – George Dorris Elizabeth Kendall 71 100 Check It Out Paul Parish Nancy Reynolds James Sutton David Vaughan Edward Willinger Cover Photograph by Stephanie Berger, BAM : Silas Riener Sarah C. -

Study of the Body Dimensions of Elite Professional Ballet Dancers

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Documento descargado de http://www.apunts.org el 25/01/2011. Copia para uso personal, se prohíbe la transmisión de este documento por cualquier medio o formato. provided by Revistes Catalanes amb Accés Obert 3 ORIGINAL ARTICLES Study of the body dimensions of elite professional ballet dancers HAMLET BETANCOURT LEÓNa, JULIETA ARÉCHIGA VIRAMONTESb, CARLOS MANUEL RAMÍREZ GARCÍAc AND MARIA ELENA DÍAZ SÁNCHEZd aAutonomous Metropolitan University. Iztapalapa Unit. México. bInstitute of Anthropological Research. UNAM. Mexico. bNational Technical Institute. Mexico. cInstitute of Nutrition and Food Hygiene. Cuba. ABstract RESUMEN The similarities and differences in the body dimensions of a Las diferencias o similitudes referidas a los tamaños absolu- group of ballet dancers compared with those of modern or tos de un grupo de bailarines de ballet frente a bailarines de folklore dances are indicators of corporal heterogeneity or danza moderna y folclórica son indicadores de variabilidad homogeneity and of the spatial volume occupied by a group o de la homogeneidad corporal y de la expresión del volu- of dancers. The present study aimed to analyze the kinan- men espacial que ocupa un grupo de danzantes. Este traba- thropometric similarities and differences among elite pro- jo se propuso analizar las similitudes y las diferencias ci- fessional ballet dancers compared with modern and folk- neantropométricas de los tamaños absolutos entre los lore dancers. The anthropometric profiles of dancers from bailarines profesionales de elite de ballet respecto a los de the National Ballet, National Dance and National Folkloric danza moderna y folclórica. -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with Arthur Mitchell

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with Arthur Mitchell Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Mitchell, Arthur, 1934-2018 Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with Arthur Mitchell, Dates: October 5, 2016 Bulk Dates: 2016 Physical 9 uncompressed MOV digital video files (4:21:20). Description: Abstract: Dancer, choreographer, and artistic director Arthur Mitchell (1934 - 2018 ) was a principal dancer for the New York City Ballet for fifteen years. In 1969, he co-founded the Dance Theatre of Harlem, the first African American classical ballet company and school. Mitchell was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on October 5, 2016, in New York, New York. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2016_034 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Dancer, choreographer and artistic director Arthur Mitchell was born on March 27, 1934 in Harlem, New York to Arthur Mitchell, Sr. and Willie Hearns Mitchell. He attended the High School of Performing Arts in Manhattan. In addition to academics, Mitchell was a member of the New Dance Group, the Choreographers Workshop, Donald McKayle and Company, and High School of Performing Arts’ Repertory Dance Company. After graduating from high school in 1952, Mitchell received scholarships to attend the Dunham School and the School of American received scholarships to attend the Dunham School and the School of American Ballet. In 1954, Mitchell danced on Broadway in House of Flowers with Geoffrey Holder, Louis Johnson, Donald McKayle, Alvin Ailey and Pearl Bailey. -

In the Zone with Dance Theatre of Harlem by Lynn Matluck Brooks

Photo: Rachel Neville In the Zone with Dance Theatre of Harlem by Lynn Matluck Brooks Although they were playing in Philadelphia directly opposite Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater—a company that competes for similar audiences—Dance Theatre of Harlem (DTH) drew a full house at the Annenberg Center (University of Pennsylvania). In that house on Saturday evening was the founder of Philadelphia Dance Company (PHILADANCO), Joan Myers Brown, who has ignited generations of dancers, particularly black dancers, in this city. Brown received a warm ovation when one of her former dancers, Robert Garland, acknowledged her from the Annenberg stage. Garland, DTH’s first Resident Choreographer, graciously acknowledged his Philly roots, his family, and his start with ’Danco. He then shared with the audience that the dancers from DTH and Ailey had gathered earlier with Brown and ’Danco to celebrate Brown’s contributions to their artistic trajectories and to the art of dance in Philly and beyond. That mood of warm, familial celebration set us up for the dancing that followed. Thus, it was apt that Garland chose to premiere his new work, Nyman String Quartet No. 2, in Philadelphia, as the program-opener. The work mixed contrasting signals that I found difficult to reconcile: the ten dancers wore lush pink-and-purple costumes and flashed showy, virtuosic dance phrases, set against the minimalist shifts of Nyman’s music and the stripped-to-the-bare-walls backstage and wings. Oddly, the extra space this staging choice allowed the dancers—who certainly can move big!—remained unused, essentially unacknowledged. Garland sent the dancers onto the stage in varied groupings that alternated and occasionally intermixed boogie with batterie, bopping with bourrees, hip thrusts and shoulder circles with split-leaps and chasses. -

'In Ballet You Need to Be Perfect'

‘In ballet you need to be perfect’ Ivan Vasiliev Rudolph Nureyev Ivan Vasiliev is a Russian ballet dancer. He is the principal dancer with the American Ballet Theatre. I live in a flat in St Petersburg with my girlfriend. I usually get up at about nine and then I have a shower. In my job I often stay in hotels. When you have a shower in the morning in a hotel you can leave your towel on the floor. I love that! I always have a good breakfast, and I love eggs. When I am very hungry, I sometimes eat five. I like sausages, too. Classes start at 10.30. I practise all morning without a break. I sometimes have lunch, but not always. In the afternoon, I practise more. Of course in ballet, you need to be perfect. Nureyev is my favourite dancer. I have a pair of his ballet shoes. After work I want to eat. I love meat. My favourite is a big steak. No vegetables. Only steak. English File third edition Beginner • Student’s Book • Unit 6B, p.37 © Oxford University Press 2015 1 In the evening we sometimes go out. Before we go out my girlfriend looks at my clothes and she usually says: “No, Ivan. Change!” I’m not interested in clothes, but I love watches. I have seven, including a Montblanc, three Rolexes, and a Maurice Lacroix. Sometimes, I don’t go to bed until 1.00 or 2.00. It’s often difficult to sleep. I have a lot of things in my head. -

A Conversation with Gelsey Kirkland & Misha Chernov

Spring 2010 Ballet Revi ew From the Spring 2010 issue of Ballet Review A Conversation with Gelsey Kirkland and Misha Chernov On the cover: New York City Ballet’s Tiler Peck in Peter Martins’ The Sleeping Beauty. 4 New York – Alice Helpern 7 Stuttgart – Gary Smith 8 Lisbon – Peter Sparling 10 Chicago – Joseph Houseal 11 New York – Sandra Genter 13 Ann Arbor – Peter Sparling 16 New York – Sandra Genter 17 Toronto – Gary Smith 19 New York – Marian Horosko 20 San Francisco – Paul Parish David Vaughan 45 23 Paris 1909-2009 Sandra Genter 29 Pina Bausch (1940-2009) Laura Jacobs & Joel Lobenthal 31 A Conversation with Gelsey Kirkland & Misha Chernov Marnie Thomas Wood Edited by 37 Celebrating the Graham Anti-heroine Francis Mason Morris Rossabi Ballet Review 38.1 51 41 Ulaanbaatar Ballet Spring 2010 Darrell Wilkins Associate Editor and Designer: 45 A Mary Wigman Evening Marvin Hoshino Daniel Jacobson Associate Editor: 51 La Danse Don Daniels Associate Editor: Michael Langlois Joel Lobenthal 56 ABT 101 Associate Editor: Joel Lobenthal Larry Kaplan 61 Osipova’s Season Photographers: 37 Tom Brazil Davie Lerner Costas 71 A Conversation with Howard Barr Subscriptions: Don Daniels Roberta Hellman 75 No Apologies: Peck &Mearns at NYCB Copy Editor: Barbara Palfy Annie-B Parson 79 First Class Teachers Associates: Peter Anastos 88 London Reporter – Clement Crisp Robert Gres kovic 93 Alfredo Corvino – Elizabeth Zimmer George Jackson 94 Music on Disc – George Dorris Elizabeth Kendall 23 Paul Parish 100 Check It Out Nancy Reynolds James Sutton David Vaughan Edward Willinger Cover photo by Paul Kolnik, New York City Ballet: Tiler Peck Sarah C. -

22 by Gretchen Horlacher a Fundamental Issue in the Analysis Of

Sketches and Superimposition in Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms by Gretchen Horlacher A fundamental issue in the analysis of Stravinsky’s music is to describe how the composer juxtaposes and superimposes repeating motivic fragments. Do layered ostinati spin out in opposition to one another or do they interact? Does the progress of one affect the progress of another? Do they create for- mal relationships beyond their own repetitions? Evidence in sketches for works spanning the Russian period through the early serial work Agon (1953–57) suggests that this issue was a primary concern for the composer: many sketches and drafts are dedicated to working out the relationships be- tween and among simultaneously sounding strata so that they jointly shape passages of music. These documents share a common working method. Early in the composi- tional process, Stravinsky seems often to have drafted short “phrases” where the constituent motivic fragments are placed in relationship but repeated only briefly or not at all; subsequent drafts expand the lengths of phrases by in- serting repetitions of existing material into the original phrases.1 Such a pro- cedure allows us to compare the longer (and most often retained) versions with their shorter predecessors, giving us insight both into how Stravinsky develops his material and what might constitute a complete formal unit. In other words, we can trace the expansions of phrases through interpolation in order to identify how later versions have a more continuous formal shape and fit more easily into larger formal units. Consider as an example two sketches for a passage from the third move- ment of the Symphony of Psalms (1929–30); the two sketches are reproduced as Examples 1a and 1b and the final score is reproduced as Example 2.2 A pre- liminary description of the passage might go as follows. -

18Th Century Dance

18TH CENTURY DANCE THE 1700’S BEGAN THE ERA WHEN PROFESSIONAL DANCERS DEDICATED THEIR LIFE TO THEIR ART. THEY COMPETED WITH EACH OTHER FOR THE PUBLIC’S APPROVAL. COMING FROM THE LOWER AND MIDDLE CLASSES THEY WORKED HARD TO ESTABLISH POSITIONS FOR THEMSELVES IN SOCIETY. THINGS HAPPENING IN THE WORLD IN 1700’S A. FRENCH AND AMERICAN REVOLUTIONS ABOUT TO HAPPEN B. INDUSTRIALIZATION ON THE WAY C. LITERACY WAS INCREASING DANCERS STROVE FOR POPULARITY. JOURNALISTS PROMOTED RIVALRIES. CAMARGO VS. SALLE MARIE ANNE DE CUPIS DE CAMARGO 1710 TO 1770 SPANISH AND ITALIAN BALLERINA BORN IN BRUSSELS. SHE HAD EXCEPTIONAL SPEED AND WAS A BRILLIANT TECHNICIAN. SHE WAS THE FIRST TO EXECUTE ENTRECHAT QUATRE. NOTEWORTHY BECAUSE SHE SHORTENED HER SKIRT TO SEE HER EXCEPTIONAL FOOTWORK. THIS SHOCKED 18TH CENTURY STANDARDS. SHE POSSESSED A FINE MUSICAL SENSE. MARIE CAMARGO MARIE SALLE 1707-1756 SHE WAS BORN INTO SHOW BUSINESS. JOINED THE PARIS OPERA SALLE WAS INTERESTED IN DANCE EXPRESSING FEELINGS AND PORTRAYING SITUATIONS. SHE MOVED TO LONDON TO PUT HER THEORIES INTO PRACTICE. PYGMALION IS HER BEST KNOWN WORK 1734. A, CREATED HER OWN CHOREOGRAPHY B. PERFORMED AS A DRAMATIC DANCER C. DESIGNED DANCE COSTUMES THAT SUITED THE DANCE IDEA AND ALLOWED FREEDOM OF MOVEMENT MARIE SALLE JEAN-GEORGES NOVERRE 1727-1820; MOST FAMOUS PERSON OF 18TH CENTURY DANCE. IN 1760 WROTE LETTERS ON DANCING AND BALLETS, A SERIES OF ESSAYS ATTACKING CHOREOGRAPHY AND COSTUMING OF THE DANCE ESTABLISHMENT ESPECIALLY AT PARIS OPERA. HE EMPHASIZED THAT DANCE WAS AN ART FORM OF COMMUNICATION: OF SPEECH WITHOUT WORDS. HE PROVED HIS THEORIES BY CREATING SUCCESSFUL BALLETS AS BALLET MASTER AT THE COURT OF STUTTGART. -

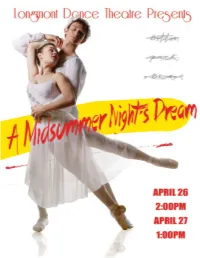

AMND-Program-Final.Pdf

ARTISTIC DIRECTOR KRISTIN KINGSLEY Story & Selected Lyrics from WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE Music by FELIX MENDELSSOHN Ballet Mistress STEPHANIE TULEY Music Director/Conductor BRANDON MATTHEWS Production Design SEAN COCHRAN Technical Director ISAIAH BOOTHBY Lighting Design DAVID DENMAN Costume Design NAOMI PRENDERGAST, SUSIE FAHRING, ANN MARCECA, & WANDA RICE WITH STRACCI FOR DANCE NIWOT HIGH SCHOOL AUDITORIUM APRIL 26 2:00PM APRIL 27 1:00PM Longmont Dance Theatre Our mission is simply stated but it is not simple to achieve: we strive to enliven and elevate the human spirit by means of dance, specifically the perfect form of dance known as ballet. A technique of movement that was born in the courts of kings and queens, ballet has survived to this day to become one of the most elegant, most adaptable and most powerful means of human communication. ARTISTIC DIRECTOR BALLET MISTRESS Kristin Kingsley Stephanie Tuley LDT BOARD OF DIRECTORS RESIDENT OPERATION PERSONNEL President Susan Burton Production & Design Vice President Dolores Kingsley Lighting Designer/ David Denman Secretary Marcella Cox Production Stage Manager Members Sean Cochran, Jeanine Hedstrom, Eileen Hickey, Stage Manager Jenn Zavattaro David Kingsley, & Moriah Sullivan Technical Dir./Master Carpenter Isaiah Boothby Ballet Guild Liason Cathy McGovern Scenic Design & Fabrication Sean Cochran with Enigma Concepts and Designs Properties Coordinator Lisa Taft House Manager Marcella Cox RESIDENT COMPANY MANAGEMENT Auditorium Manager Jason Watkins (Niwot HS Auditorium) Willow McGinty Office -

AM Tanny Bio FINAL

Press Contact: Natasha Padilla, WNET 212.560.8824, [email protected] Press Materials: http://pbs.org/pressroom or http://thirteen.org/pressroom Websites: http://pbs.org/americanmasters , http://facebook.com/americanmasters , @PBSAmerMasters , http://pbsamericanmasters.tumblr.com , http://youtube.com/AmericanMastersPBS , #AmericanMasters American Masters Tanaquil Le Clercq: Afternoon of a Faun Premieres nationally Friday, June 20, 10-11:30 p.m. on PBS (check local listings) Tanaquil Le Clercq Bio Born in Paris in 1929, Tanaquil was the daughter of a French intellectual and a society matron from St. Louis. When Tanny was 3, they moved to New York where Jacques Le Clercq taught romance languages. Tanny began ballet training in New York at age 5, studying with Mikhail Mordkin. She eventually transitioned to the School of American Ballet, which George Balanchine had founded in 1934. Balanchine discovered Tanny as a student there. He cast her as Choleric in The Four Temperaments at the tender age of 15, along with the great prima ballerinas in his company, then called Ballet Society. Before long she was dancing solo roles as a member of Ballet Society, never having danced in the corps de ballet. Some of Balanchine’s most memorable ballets were choreographed on Tanny; notably Symphony in C, La Valse, Concerto Barocco and Western Symphony . She was the original Dew Drop in The Nutcracker. Jerome Robbins was also fascinated with Tanny; famously attributing his enchantment with her unique style of dancing with his decision to join the New York City Ballet and work under Balanchine as both a dancer and choreographer. It was there he created his radical version of Afternoon of a Faun on Tanny.