Alexander's Silver Coins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antik Çağ'da Doğu-Bati Mücadelesi Kapsaminda

T.C. BURSA ULUDAĞ ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ TARİH ANABİLİM DALI ESKİÇAĞ BİLİM DALI ANTİK ÇAĞ’DA DOĞU-BATI MÜCADELESİ KAPSAMINDA ROMA-PART İLİŞKİLERİ (Yüksek Lisans Tezi) Serhat Pir TOSUN BURSA 2020 T.C. BURSA ULUDAĞ ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ TARİH ANABİLİM DALI ESKİÇAĞ BİLİM DALI ANTİK ÇAĞ’DA DOĞU-BATI MÜCADELESİ KAPSAMINDA ROMA-PART İLİŞKİLERİ (Yüksek Lisans Tezi) Serhat Pir TOSUN Danışman: Dr. Öğr. Üyesi Kamil DOĞANCI BURSA 2020 YEMİN METNİ Yüksek Lisans / Doktora Tezi/Sanatta Yeterlik Tezi/ Çalışması olarak sunduğum “Antik Çağ’da Doğu-Batı Mücadelesi Kapsamında Roma-Part İlişkileri” başlıklı çalışmanın bilimsel araştırma, yazma ve etik kurallarına uygun olarak tarafımdan yazıldığına ve tezde yapılan bütün alıntıların kaynaklarının usulüne uygun olarak gösterildiğine, tezimde intihal ürünü cümle veya paragraflar bulunmadığına şerefim üzerine yemin ederim. 30/03/2020 Adı Soyadı: Serhat Pir TOSUN Öğrenci No:701742007 Anabilim/Anasanat Dalı: Tarih Programı: Tezli Yüksek Lisans Statüsü: Yüksek Lisans Doktora : Sanatta Yeterlik ÖZET Yazarın Adı ve Soyadı : Serhat Pir TOSUN Üniversite : Bursa Uludağ Üniversitesi Enstitüsü : Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Anabilim Dalı : Tarih Bilim Dalı : Eskiçağ Tarihi Bilim Dalı Tezin Niteliği : Yüksek Lisans Tezi Sayfa Sayısı : xv+156 Mezuniyet Tarihi : …. /…. / 2020 Tez Danışmanı : Dr. Öğr. Üyesi Kamil DOĞANCI ANTİK ÇAĞ’DA DOĞU-BATI MÜCADELESİ KAPSAMINDA ROMA-PART İLİŞKİLERİ MÖ 92 yılında başlayan Roma-Part ilişkileri MÖ 53 yılına kadar dostane bir şekilde devam etmiş, ancak MÖ I. yüzyılda ortaya çıkan Armenia problemi nedeniyle ilişkiler bozulmuştur. MÖ 53 yılında Syria’ya proconsul olarak atanan Romalı General Marcus Licinius Crassus, bir süre sonra Part seferi hazırlıklarına başlamıştır. MÖ 53 yılında sefere çıkan Crassus, Carrhae’de büyük bir hezimete uğramış, kendisi ve oğlu öldürülmüş, lejyon sancağı Part ordusu tarafından ele geçirilmiştir. -

09-Khodadad-Rezakhani-02.Pdf

Samuel Jordan Center for Persian Studies and Culture www.dabirjournal.org Digital Archive of Brief notes & Iran Review ISSN: 2470-4040 Vol.01 No.03.2017 1 xšnaoθrahe ahurahe mazdå Detail from above the entrance of Tehran’s fire temple, 1286š/1917–18. Photo by © Shervin Farridnejad The Digital Archive of Brief notes & Iran Review (DABIR) ISSN: 2470-4040 www.dabirjournal.org Samuel Jordan Center for Persian Studies and Culture University of California, Irvine 1st Floor Humanities Gateway Irvine, CA 92697-3370 Editor-in-Chief Touraj Daryaee (University of California, Irvine) Editors Parsa Daneshmand (Oxford University) Arash Zeini (Freie Universität Berlin) Shervin Farridnejad (Freie Universität Berlin) Book Review Editor Shervin Farridnejad (Freie Universität Berlin) Editorial Assistants Ani Honarchian (UCLA) Sara Mashayekh (UCI) Advisory Board Samra Azarnouche (École pratique des hautes études); Dominic P. Brookshaw (Oxford University); Matthew Canepa (University of Minnesota); Ashk Dahlén (Uppsala University) Peyvand Firouzeh (Cambridge University); Leonardo Gregoratti (Durham University); Frantz Grenet (Collège de France); Wouter F.M. Henkelman (École Pratique des Hautes Études); Rasoul Jafarian (Tehran University); Nasir al-Ka‘abi (University of Kufa); Andromache Karanika (UC Irvine); Agnes Korn (Goethe Universität Frankfurt am Main); Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones (University of Edinburgh); Jason Mokhtarain (University of Indiana); Ali Mousavi (UC Irvine); Mahmoud Omidsalar (CSU Los Angeles); Antonio Panaino (University of Bologna); Alka Patel (UC Irvine); Richard Payne (University of Chicago); Khoda- dad Rezakhani (Princeton University); Vesta Sarkhosh Curtis (British Museum); M. Rahim Shayegan (UCLA); Rolf Strootman (Utrecht University); Giusto Traina (University of Paris-Sorbonne); Mohsen Zakeri (University of Göttingen) Logo design by Charles Li Layout and typesetting by Kourosh Beighpour Contents Notes 1. -

Marina Gavryushkina UC Berkeley Art History 2013

UC Berkeley Berkeley Undergraduate Journal of Classics Title The Persian Alexander: The Numismatic Portraiture of the Pontic Dynasty Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7xh6g8nn Journal Berkeley Undergraduate Journal of Classics, 2(1) ISSN 2373-7115 Author Gavryushkina, Marina Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Undergraduate eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Gavryushkina 1 The Persian Alexander: The Numismatic Portraiture of the Pontic Dynasty Marina Gavryushkina UC Berkeley Art History 2013 Abstract: Hellenistic coinage is a popular topic in art historical research as it is an invaluable resource of information about the political relationship between Greek rulers and their subjects. However, most scholars have focused on the wealthier and more famous dynasties of the Ptolemies and the Seleucids. Thus, there have been considerably fewer studies done on the artistic styles of the coins of the smaller outlying Hellenistic kingdoms. This paper analyzes the numismatic portraiture of the kings of Pontus, a peripheral kingdom located in northern Anatolia along the shores of the Black Sea. In order to evaluate the degree of similarity or difference in the Pontic kings’ modes of representation in relation to the traditional royal Hellenistic style, their coinage is compared to the numismatic depictions of Alexander the Great of Macedon. A careful art historical analysis reveals that Pontic portrait styles correlate with the individual political motivations and historical circumstances of each king. Pontic rulers actively choose to diverge from or emulate the royal Hellenistic portrait style with the intention of either gaining support from their Anatolian and Persian subjects or being accepted as legitimate Greek sovereigns within the context of international politics. -

Tome 25 - 1996 - Fascicule 2

EXTRAIT Tome 25 - 1996 - fascicule 2 PUBLIE PAR L'ASSOCIATION POUR L'AVANCEMENT DES ETUDES IRANIENNES AVEC LE CONCOURS DU CENTRE NATIONAL DE LA RECHERCHE SCIENTIFIQUE 1 Frantz GRENET et Osmund BOPEARACHCHI CNRS, PARIS UNE MONNAIE EN OR DU SOUVERAIN INDO-PARTHE ABDAGASES II La pièce qui fait I' objet de cet article a, selon notre informateur M. Muhammad Riaz Babar, été trouvée par un habitant de Chilas (près de Gilgit) dont il a directement recueilli le témoignage. Ce villageois, en récupérant des pierres taillées dans les ruines d'un ancien monument pour construire sa maison, a mis au jour un vase en terre cuite contenant, entre autres, la pièce d'or en question, un bracelet en bronze, et des perles en corail, en verre bleu et jaune et en terre cuite (Fig. I). Nous n'avons malheureusement pas pu examiner directement cette pièce et il faut signaler que nos observations sont faites a partir des photographies (Fig. 2) qui nous a été envoyées par M.R. Babar a qui nous exprimons notre sincère reconnaissance. Joe Cribb, conservateur des monnaies orientales du British Museum, qui a eu la pièce entre les mains, a bien voulu nous communiquer un certain nombre de renseignements précieux auxquels nous ferons allusion lorsque nous discuterons la question de son authenticité. Cette pièce est depuis entrée dans la collection privée du professeur Ikuo Hirayama, au Japon, et il nous a aimablement autorises à la publier. DESCRIPTION Avers: Buste drape du souverain à g., coiffé d'un tiare haute et arrondie surmontée de plusieurs rangs de perles, avec à l'arrière un nœud surmontant un long ruban flottant, et tenant en face une flèche. -

Seleucid Coinage and the Legend of the Horned Bucephalas

Seleucid coinage and the legend of the horned Bucephalas Autor(en): Miller, Richard P. / Walters, Kenneth R. Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Schweizerische numismatische Rundschau = Revue suisse de numismatique = Rivista svizzera di numismatica Band (Jahr): 83 (2004) PDF erstellt am: 04.10.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-175883 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch RICHARD P. MILLER AND KENNETH R.WALTERS SELEUCID COINAGE AND THE LEGEND OF THE HORNED BUCEPHALAS* Plate 8 [21] Balaxian est provincia quedam, gentes cuius Macometi legem observant et per se loquelam habent. Magnum quidem regnum est. Per successionem hereditariam regitur, quae progenies a rege Alexandra descendit et a filia regis Darii Magni Persarum... -

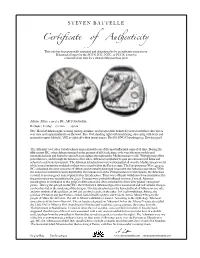

Ceificate of Auenticity

S T E V E N B A T T E L L E Ce!ificate of Au"enticity This coin has been personally inspected and determined to be an authentic ancient coin . If deemed a forgery by the ACCS, IGC, NGC, or PCGS, it may be returned at any time for a refund of the purchase price. Athens, Attica, 449-404 BC, AR Tetradrachm B076961 / U02697 17.1 Gm 25 mm Obv: Head of Athena right, wearing earring, necklace, and crested Attic helmet decorated with three olive leaves over visor and a spiral palmette on the bowl. Rev: Owl standing right with head facing, olive sprig with berry and crescent in upper left field, AOE to right; all within incuse square. Kroll 8; SNG Copenhagen 31; Dewing 1591-8 The Athenian “owl” silver tetradrachm is unquestionably one of the most influential coins of all time. During the fifth century BC, when Athens emerged as the greatest of all Greek cities, owls were the most widely used international coin and helped to spread Greek culture throughout the Mediterranean world. With the help of her powerful navy, and through the taxation of her allies, Athens accomplished to gain pre-eminance in Hellas and achieved a celebrated prosperity. The Athenian tetradrachms were well-accepted all over the Mediterranean world, while several imitations modeled on them were issued within the Persian state. The Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC) exhausted the silver resources of Athens and eventually destroyed irreparably the Athenian supremacy. With the mines lost and their treasury depleted by the ruinous cost of the Pelloponesian war with Sparta, the Athenians resorted to an emergency issue of plated silver tetradrachms. -

The Politics of Parthian Coinage in Media

The Politics of Parthian Coinage in Media Author(s): Farhang Khademi Nadooshan, Seyed Sadrudin Moosavi, Frouzandeh Jafarzadeh Pour Reviewed work(s): Source: Near Eastern Archaeology, Vol. 68, No. 3, Archaeology in Iran (Sep., 2005), pp. 123-127 Published by: The American Schools of Oriental Research Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25067611 . Accessed: 06/11/2011 07:31 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The American Schools of Oriental Research is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Near Eastern Archaeology. http://www.jstor.org The Parthians (174 BCE-224CE) suc- , The coins discussed here are primarily from ceeded in the the Lorestan Museum, which houses the establishing longest jyj^' in the ancient coins of southern Media.1 However, lasting empire J0^%^ 1 Near East.At its Parthian JF the coins of northern Media are also height, ^S^ considered thanks to the collection ruleextended Anatolia to M from ^^^/;. housed in the Azerbaijan Museum theIndus and the Valley from Ef-'?S&f?'''' in the city of Tabriz. Most of the Sea to the Persian m Caspian ^^^/// coins of the Azerbaijan Museum Farhang Khademi Gulf Consummate horsemen el /?/ have been donated by local ^^ i Nadooshan, Seyed indigenoustoCentral Asia, the ? people and have been reported ?| ?????J SadrudinMoosavi, Parthians achieved fame for Is u1 and documented in their names. -

Marathon 2,500 Years Edited by Christopher Carey & Michael Edwards

MARATHON 2,500 YEARS EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS BULLETIN OF THE INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SUPPLEMENT 124 DIRECTOR & GENERAL EDITOR: JOHN NORTH DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS: RICHARD SIMPSON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS PROCEEDINGS OF THE MARATHON CONFERENCE 2010 EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 The cover image shows Persian warriors at Ishtar Gate, from before the fourth century BC. Pergamon Museum/Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin. Photo Mohammed Shamma (2003). Used under CC‐BY terms. All rights reserved. This PDF edition published in 2019 First published in print in 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN: 978-1-905670-81-9 (2019 PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/1019.9781905670819 ISBN: 978-1-905670-52-9 (2013 paperback edition) ©2013 Institute of Classical Studies, University of London The right of contributors to be identified as the authors of the work published here has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Designed and typeset at the Institute of Classical Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory note 1 P. J. Rhodes The battle of Marathon and modern scholarship 3 Christopher Pelling Herodotus’ Marathon 23 Peter Krentz Marathon and the development of the exclusive hoplite phalanx 35 Andrej Petrovic The battle of Marathon in pre-Herodotean sources: on Marathon verse-inscriptions (IG I3 503/504; Seg Lvi 430) 45 V. -

Copyrighted Material

Index Note : Geographical landmarks are listed under the proper name itself: for “Cape Sepias” or “Mt. Athos” see “Sepias” or “Athos.” When a people and a toponym share the same base, see under the toponym: for “Thessalians” see “Thessaly.” Romans are listed according to the nomen, i.e. C. Julius Caesar. With places or people mentioned once only, discretion has been used. Abdera 278 Aeaces II 110, 147 Abydus 222, 231 A egae 272–273 Acanthus 85, 207–208, 246 Aegina 101, 152, 157–158, 187–189, Acarnania 15, 189, 202, 204, 206, 251, 191, 200 347, 391, 393 Aegium 377, 389 Achaia 43, 54, 64 ; Peloponnesian Aegospotami 7, 220, 224, 228 Achaia, Achaian League 9–10, 12–13, Aemilius Paullus, L. 399, 404 54–56, 63, 70, 90, 250, 265, 283, 371, Aeolis 16–17, 55, 63, 145, 233 375–380, 388–390, 393, 397–399, 404, Aeschines 281, 285, 288 410 ; Phthiotic Achaia 16, 54, 279, Aeschylus 156, 163, 179 286 Aetoli Erxadieis 98–101 Achaian War 410 Aetolia, Aetolian League 12, 15, 70, Achaius 382–383, 385, 401 204, 250, 325, 329, 342, 347–348, Acilius Glabrio, M. 402 376, 378–380, 387, 390–391, 393, Acragas 119, COPYRIGHTED165, 259–261, 263, 266, 39MATERIAL6–397, 401–404 352–354, 358–359 Agariste 113, 117 Acrocorinth 377, 388–389 Agathocles (Lysimachus ’ son) 343, 345 ; Acrotatus 352, 355 (King of Sicily) 352–355, 358–359; Actium 410, 425 (King of Bactria) 413–414 Ada 297 Agelaus 391, 410 A History of Greece: 1300 to 30 BC, First Edition. Victor Parker. -

Mercenaries, Poleis, and Empires in the Fourth Century Bce

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts ALL THE KING’S GREEKS: MERCENARIES, POLEIS, AND EMPIRES IN THE FOURTH CENTURY BCE A Dissertation in History and Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies by Jeffrey Rop © 2013 Jeffrey Rop Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2013 ii The dissertation of Jeffrey Rop was reviewed and approved* by the following: Mark Munn Professor of Ancient Greek History and Greek Archaeology, Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Gary N. Knoppers Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies, Religious Studies, and Jewish Studies Garrett G. Fagan Professor of Ancient History and Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies Kenneth Hirth Professor of Anthropology Carol Reardon George Winfree Professor of American History David Atwill Associate Professor of History and Asian Studies Graduate Program Director for the Department of History *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT This dissertation examines Greek mercenary service in the Near East from 401- 330 BCE. Traditionally, the employment of Greek soldiers by the Persian Achaemenid Empire and the Kingdom of Egypt during this period has been understood to indicate the military weakness of these polities and the superiority of Greek hoplites over their Near Eastern counterparts. I demonstrate that the purported superiority of Greek heavy infantry has been exaggerated by Greco-Roman authors. Furthermore, close examination of Greek mercenary service reveals that the recruitment of Greek soldiers was not the purpose of Achaemenid foreign policy in Greece and the Aegean, but was instead an indication of the political subordination of prominent Greek citizens and poleis, conducted through the social institution of xenia, to Persian satraps and kings. -

Hellenistic Central Asia: Current Research, New Directions

Hellenistic Central Asia: Current Research, New Directions Inaugural Colloquium of the Hellenistic Central Asia Research Network (HCARN) Department of Classics, University of Reading (UK) 15-17 April 2016 ABSTRACTS All conference sessions will be held in Lecture Room G 15, Henley Business School, University of Reading Whiteknights Campus. Baralay, Supratik (University of Oxford) The Arsakids between the Seleucids and the Achaemenids Abstract pending. Bordeaux, Olivier (Paris-Sorbonne) Graeco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek numismatics: Methodologies, new research and limits Numismatics is one of the leading fields in Hellenistic Central Asia studies, since it has enabled historians to identify 45 different Graeco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek kings, while written sources only speak of 10. The coins struck by the Greek kings are often remarkable, both because of their quality and the multiple innovations some of them show: Indian iconography, local language (Brahmi or Kharoshthi), new weight system, etc. Yet, broad studies by properly trained numismatists still remained scarce, while new coins mainly find their origin on the art market rather than archaeological digs. The current situation in Central Asia, especially in Afghanistan and Pakistan, does not help archaeologists to broaden their fieldwork. Die-studies are more and more often the methodology followed by the numismatists in the last decade, so as to draw as much data as possible from large corpora. During our PhD research, we focused on six kings: Diodotus I and II, Euthydemus I, Eucratides I, Menander I and Hippostratus. Beyond individual results and hypothesis, we tried to ascertain this particular methodology regarding Central Asia Greek coinages. Generally, our die-studies provided good outcomes, while most of our attempts to geographically locate mints or even borders remain quite fragile, in the lack of archaeological data. -

Notes on the Yuezhi - Kushan Relationship and Kushan Chronology”, by Hans Loeschner

“Notes on the Yuezhi - Kushan Relationship and Kushan Chronology”, by Hans Loeschner Notes on the Yuezhi – Kushan Relationship and Kushan Chronology By Hans Loeschner Professor Michael Fedorov provided a rejoinder1 with respect to several statements in the article2 “A new Oesho/Shiva image of Sasanian ‘Peroz’ taking power in the northern part of the Kushan empire”. In the rejoinder Michael Fedorov states: “The Chinese chronicles are quite unequivocal and explicit: Bactria was conquered by the Ta-Yüeh-chih! And it were the Ta-Yüeh-chih who split the booty between five hsi-hou or rather five Ta-Yüeh-chih tribes ruled by those hsi-hou (yabgus) who created five yabguates with capitals in Ho-mo, Shuang-mi, Hu-tsao, Po-mo, Kao-fu”. He concludes the rejoinder with words of W.W. Tarn3: “The new theory, which makes the five Yüeh- chih princes (the Kushan chief being one) five Saka princes of Bactria conquered by the Yüeh- chih, throws the plain account of the Hou Han shu overboard. The theory is one more unhappy offshoot of the elementary blunder which started the belief in a Saka conquest of Greek Bactria”.1 With respect to the ethnical allocation of the five hsi-hou Laszlo Torday provides an analysis with a result which is in contrast to the statement of Michael Fedorov: “As to the kings of K’ang- chü or Ta Yüeh-shih, those chiefs of foreign tribes who acknowledged their supremacy were described in the Han Shu as “lesser kings” or hsi-hou. … The hsi-hou (and their fellow tribespeople) were ethnically as different from the Yüeh-shih and K’ang-chü as were the hou… from the Han.