La Cimade and Non-Governmental Aid for Migrants in Southern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sinfo-December-2013.Pdf

12 ISSN 1854-0805 December 2013 The latest from Slovenia ON THE POLITICAL AGENDA INTERVIEW: Miroslav Mozetič, MSc IN FOCUS INTERVIEW: Dr Bojana Rogelj Škafar HERITAGE: Slovenian Potica Polona Anja Valerija Tanja Irena Vesna Let this New Year be the one, where all your dreams come true, so with a joyful heart, put a start to this year anew. Wishing you a happy and prosperous New Year 2014. Editorial Board CONTEnts EDITORIAL ON THE POLITICAL AGENDA INTERVIEW 7 Miroslav Mozetič, MSc Photo: Bruno Toič In these times of financial and social crisis, the Consti- tutional Court faces new chalenges A Photo: Tamino Petelinšek/ST Tamino Photo: IN FOCUS INTERVIEW 14 Dr Bojana Rogelj Škafar Tanja Glogovčan, editor Research and communicating our knowledge of the wealth of ethnological heritage are of key importance A few of this year’s events to inspire you for the year to come Our December issue being focused on Slovenian ethnological Photo: Personal archives Personal Photo: characteristics, we are delighted to present below the work and success of the Slovene Ethnographic Museum, viewed through the experience of its Director, Dr Bojana Rogelj Škafar, and its permanent exhibition entitled “The Relationship between Nature and Culture”. The forthcoming year will mark the 600th anniversary of the beginning of the enthronement rituals of the Carinthian dukes, which has since been one of the most important distinctions of Slovenia in the European area and is also one of the topics dealt with in this issue. HERITAGE 28 Dr Janez Bogataj There is no holiday in Slovenia without the traditional Slovenian Slovenian potica festive cake potica. -

The GRT Achievement Programme 2006/8

Li Sobindoy –Roma in Action Edited by Dr Brian Belton Senior Lecturer YMCA George Williams College Canning Town London THIS PROJECT HAS BEEN FUNDED WITH SUPPORT FROM THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION. THIS PUBLICATION [COMMUNICATION] REFLECTS THE VIEWS ONLY OF THE AUTHORS, AND THE COMMISSION CANNOT BE HELD RESPONSIBLE FOR ANY USE WHICH MAY BE MADE OF THE INFORMATION CONTAINED THEREIN. Introduction The following is the result of a Grundvig partnership, made up of organizations from Germany, Turkey, Spain and the UK. We sought to focus at educational (formal and informal) activities, principally focusing on the position of Roma and Sinti1, transmitting something of the history, culture and values of Roma, but also suggest ways and means of responding to these socially and economically challenged groups. We also wanted to question existing non-Roma perceptions about Roma, providing some food for thought and perhaps inspiration in terms of social responses that can effectively promote the challenging of stereotyping, prejudice and discrimination, while inviting Roma to develop a level of autonomy within host societies, but also contribute to those societies as a the culturally rich, vibrant and diverse population they are. However, the core of the research is the effort to share and suggest innovative practice, approaches to and practical action for building positive relations between Roma and majority populations in the European context. This encompassed examining actual and potential responses to the causes of Roma poverty and exclusion, which we take to be part of the cause and effect of prejudice and discrimination experienced by these groups. The partnership has proved to be a valuable resource to create a platform for exchange of methods, the sharing of information and successful approaches, developing personal and group insight and providing educational activities for non-Roma about and with Roma as well as for dissemination of good practice. -

University of Dundee Enhancing Gypsy, Roma And

University of Dundee Enhancing Gypsy, Roma and Traveller peoples’ trust McFadden, Alison; Siebelt, Lindsay; Jackson, Cath; Jones, Helen; Innes, Nicola; MacGillivray, Stephen DOI: 10.20933/100001117 Publication date: 2018 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in Discovery Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): McFadden, A., Siebelt, L., Jackson, C., Jones, H., Innes, N., MacGillivray, S., ... Atkin, K. (2018). Enhancing Gypsy, Roma and Traveller peoples’ trust: using maternity and early years’ health services and dental health services as exemplars of mainstream service provision. Dundee: University of Dundee. https://doi.org/10.20933/100001117 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in Discovery Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from Discovery Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain. • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 10. Mar. 2020 Enhancing Gypsy, Roma and Traveller peoples’ trust: using maternity and early years’ health services and dental health services as exemplars of mainstream service provision Final Report September 2018 Authors and affiliations Alison McFadden1, Lindsay Siebelt1, Cath Jackson2, Helen Jones3, Nicola Innes4, Stephen MacGillivray1, Kerry Bell2, Belen Corbacho2, Anna Gavine1, Haggi Haggi1, Karl Atkin2. -

Cultural Resources for Roma Inclusion

Cultural Resources for Roma Inclusion Feasibility phase of a cultural enterprise project in Roma settlements PART 2 Prepared by: Agata Sardelič Photos: Children from the Roma settlement Kamenci Translation: INTERPRET – Romana Mlačak, s.p. Ljubljana‐SI 2 Identification of Roma Settlements/Organisations 3 The Set of Criteria for the Identification of Potential Partner Roma Settlements/Organisations We prepared the criteria for the identification of potential partner Roma settlements/organisations by bearing in mind minimum conditions for the adoption of the Kamenci development model. The criteria consist of the following 6 sets: 1. Interest for cooperation in the project In line with this criterion, we checked if an organisation that received our sent questionnaire is interested in cooperation in the Council of Europe project: “Cultural resources for Roma inclusion”. We also examined possibilities for active participation of the target Roma settlement in the project and probability for setting up a local Roma development partnership. We are of the opinion that this is one of the key prerequisites for successful (“bottom up”) planning of the development of the target Roma settlement/community. 2. Organization skills and management The second criterion pertains to the organisation’s objectives and activities as well as its HR, financial and material potentials (facilities and equipment). 3. Project experience In line with this criterion, we assessed the organisation’s project experience and its specific experience in working with the Roma population (projects/programmes/actions). 4 4. Size of the target Roma settlement and infrastructure As the Kamenci development model is best suited for smaller Roma settlements (with a population of up to 500), the adequacy of the target Roma settlement was also assessed by considering the size criterion. -

D5.2 Title: Minority Heritage Pilot Results

RE-designing Access to Cultural Heritage for a wider participation in preservation, (re-)use and management of European Culture This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement no 769827. Deliverable 5.2 number Title Minority heritage pilot results Due date Month 27 Actual date of 21 March 2020 delivery to EC Project Coordinator: Coventry University Professor Neil Forbes Priority Street, Coventry CV1 5FB, United Kingdom E-mail: [email protected] Project website address: http://www.reach-culture.eu Page 1 of 56 REACH Deliverable: D5.2 Title: Minority heritage pilot results Context: Partner responsible for ELTE deliverable Deliverable author(s) Eszter György, Gábor Sonkoly, Gábor Oláh (ELTE) and Tim Hammerton (COVUNI) Deliverable version number 1.0 Dissemination Level Public History: Change log Version Date Author Reason for change 0.1 21/01/2020 Eszter György, Gábor Sonkoly and Gábor Oláh 0.2 12/02/2020 Eszter György and Gábor Additional text added Oláh following peer review by COVUNI 1.0 21/03/2020 Eszter György and Tim Final amendments and edit Hammerton Release approval Version Date Name & organisation Role 1.0 21/03/2020 Tim Hammerton, COVUNI Project Manager Page 2 of 56 REACH Deliverable: D5.2 Title: Minority heritage pilot results Statement of originality: This deliverable contains original unpublished work except where clearly indicated otherwise. Acknowledgement of previously published material and of the work of others has been made through appropriate -

Romani | Language Roma Children Council Conseil of Europe De L´Europe in Europe Romani | Language

PROJECT EDUCATION OF ROMANI | LANGUAGE ROMA CHILDREN COUNCIL CONSEIL OF EUROPE DE L´EUROPE IN EUROPE ROMANI | LANGUAGE Factsheets on Romani Language: General Introduction 0.0 Romani-Project Graz / Dieter W. Halwachs The Roma, Sinti, Calè and many other European population groups who are collectively referred to by the mostly pejorative term “gypsies” refer to their language as Romani, Romanes or romani čhib. Linguistic-genetically it is a New Indo-Aryan language and as such belongs to the Indo-Iranian branch of the Indo-European languages. As an Indo-Aryan diaspora language which occurs only outside the Indian subcontinent, Romani has been spoken in Europe since the Middle Ages and today forms an integral part of European linguistic diversity. The first factsheet addresses the genetic and historical aspects of Romani as indicated. Four further factsheets cover the individual linguistic structural levels: lexis, phonology, morphology and syntax. This is followed by a detailed discussion of dialectology and a final presentation of the socio-linguistic situation of Romani. 1_ ROMANI: AN INDO-ARYAN LANGUAGE OF EUROPE deals with the genetic affiliation and with the history of science and linguistics of Romani and Romani linguistics. 2_ WORDS discusses the Romani lexicon which is divided into two layers: Recent loanwords from European languages are opposed by the so-called pre-European inherited lexicon. The latter allowed researchers to trace the migration route of the Roma from India to Europe. 3_ SOUNDS describes the phonology of Romani, which includes a discussion of typical Indo-Aryan sounds and of variety- specific European contact phenomena. THE OPINIONS EXPRESSED IN THIS WORK ARE THE RESPONSIBILITY OF THE AUTHORS AND DO NOT NECESSARILY REFLECT THE OFFICIAL POLICY OF THE COUNCIL OF EUROPE. -

Contribution Au Glossaire Sur Les Roms

1 HDIM.IO/218/07 27 September 2007 ORIGINAL: English Roma and Travellers Glossary Compiled by Claire PEDOTTI (French Translation Department) and Michaël GUET (DGIII Roma and Travellers Division) in consultation with the English and French Translation Departments and Aurora AILINCAI (DGIV Project «Schooling for Roma Children in Europe»). Kindly translated into English by Vincent NASH (English Translation Department). General comments: The many different terms found in Council of Europe texts and on Council websites make harmonisation of the Organisation’s usage essential. That is the purpose of this glossary, which will be up-dated regularly . This glossary reflects the current consensus. Following its suggestions is thus strongly recommended (if in doubt, use the underlined term). Last update : 11 December 2006 2 The terminology used by the Council of Europe (CoE) has varied considerably since the early 1970s : «Gypsies and other travellers»1, «nomads»2, « populations of nomadic origin»3, «Gypsies»4, «Rroma (Gypsies)»5, «Roma»6, « Roma/Gypsies»7, «Roma/Gypsies and Travellers»8, « Roms et Gens du voyage »9. Some of our decisions on terminology are based on the conclusions of a seminar held at the Council of Europe in September 2003 on «The cultural identities of Roma, Gypsies, Travellers and related groups in Europe», which was attended by representatives of the various groups in Europe (Roma, Sinti, Kale, Romanichals, Boyash, Ashkali, Egyptians, Yenish, Travellers, etc.) and of various international organisations (OSCE-ODIHR, European Commission, UNHCR and others). The question’s complexity has obliged us to lay down a number of linguistic principles, which may seem a little arbitrary. -

(Ed.) (2014) Migrating Heritage: Experiences of Cultural Networks and Cultural Dialogue in Europe

Innocenti, P., (Ed.) (2014) Migrating Heritage: Experiences of Cultural Networks and Cultural Dialogue in Europe. Ashgate, Farnham. ISBN 9781472422811 Copyright © 2014 Ashgate A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge Content must not be changed in any way or reproduced in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder(s) When referring to this work, full bibliographic details must be given http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/80836/ Deposited on: 12 December 2014 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk PREPRINT DRAFT – DO NOT CITE © Copyrighted Material Pre-press version (i.e. the final version of the text before any editorial input or formatting by the publishers) of the book chapters from: Innocenti, P. Ed. 2014. Migrating Heritage: Experiences of Cultural Networks and Cultural Dialogue in Europe. Ashgate, Aldershot, UK. ISBN 9781472422811, http://www.ashgate.com/isbn/9781472422811 The introduction of the book by Perla Innocenti is the post-press version already publicly available on Ashgate website. This pre-press version is made publicly available by the University of Glasgow in accordance to Special Clause 39 regarding Open Access agreed by the University of Glasgow as partner of the EU-funded FP7 collaborative research project European Museums in an Age of Migrations (MeLa) 2011-2014, SSH-2010-5.2-2, Grant Agreement No. 266757, and by the publisher. DO NOT CITE PREPRINT DRAFT – DO NOT CITE -

"Roma and "Gypsies"

Roma and “Gypsies” Definitions and Groups in Sweden there are both Romer and Resande (Roma and Traveller) The term “Gypsy” is commonly used as designation for the people whose correct ethnic name is Roma. However, the same word is employed also to indicate different non-Roma groups whose lifestyle is apparently similar; like some “Travellers” and other itinerant people. We are not dealing here with the derogatory implications that are ascribed to this term, but only with the respectful meaning of the word which may be acceptable as a popular term to define a community of people having distinguishable cultural features. There are also other applications of this word which are not of our interest, as for example, in reference to people whose lifestyle is regarded as unconventional ‒ in a similar way as “Bohemian” ‒ or as it is applied mainly in America, to artists who have actually not any ethnic relationship with any Gypsy group, neither Romany nor non-Romany. Therefore, we can say that there are ethnic Gypsies who are Roma, and other Gypsies who are not ethnically Roma. In this essay we intend to briefly expose about both: Romany and non-Romany Gypsies. Romany Gypsies The Roma are a well defined ethnic community, composed by groups and sub-groups having a common origin and common cultural patterns ‒ that in many cases have been modified or adapted, according to the land of sojourn and other circumstances along history. There is a common Romany Law, which several groups do not keep any longer, but still recognizing that their ancestors have observed such complex of laws until not too long time ago. -

OSCE Human Dimension Implementation Meeting Warsaw

OSCE Human Dimension Implementation Meeting Warsaw, 23 September – 3 October 2013 Contribution of the Council of Europe Follow-up to the Strasbourg Declaration on Roma September 2012 - September 2013 By the Special Representative of the Council of Europe Secretary General for Roma Issues Full information: www.coe.int/Roma INTRODUCTION The Strasbourg Declaration on Roma adopted at the CoE High-level meeting of 20 October 2010 has generated a stronger focus on action to improve the situation of the Roma in the Council of Europe member States. Using transversal methods wherever possible and involving various sectors such as Education, the Congress of Local and Regional authorities and Youth, the Council of Europe has been able to mobilize resources which are strategically important for achieving progress on the social inclusion of Roma and the full respect of their human rights. This document gives an overview of different lines and areas of action, such as the ROMED mediators training programme, the shift from standard-setting to implementation through innovations in the intergovernmental cooperation methods adopted by the CAHROM, the sharing of good practice among member states, the empowerment of Roma women, awareness raising activities through the Dosta! campaign and through the training of lawyers programme and, with the active involvement of the Congress, building capacities of national, regional and local authorities through the European Alliance of Cities and Regions for Roma Inclusion. Much of this work is carried out in cooperation -

The Phylogeography of Y-Chromosome Haplogroup H1a1a-M82 Reveals the Likely Indian Origin of the European Romani Populations | Downloaded: 13.3.2017

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bern Open Repository and Information System (BORIS) The phylogeography of Y-chromosome haplogroup H1a1a-M82 reveals the likely Indian origin of the European Romani populations | downloaded: 13.3.2017 Marek Olách, a Roma man of Slovakia Photography: Miroslav Vretenár of Ružomberok (with kind permission) by Niraj Rai, Gyaneshwer Chaubey, Rakesh Tamang, Ajai Kumar Pathak, Vipin Kumar Singh, Monika Karmin, Manvendra Singh, Deepa Selvi Rani, Sharath Anugula, Brijesh Kumar Yadav, Ashish Singh, Ramkumar Srinivasagan, Anita Yadav, Manju Kashyap, Sapna Narvariya, Alla G. Reddy, George van Driem, Peter A. Underhill, https://doi.org/10.7892/boris.46275 Richard Villems, Toomas Kivisild, Lalji Singh, Kumarasamy Thangaraj source: published online 29 November 2012$ http://www.plosone.org/article/info:doi/10.1371/journal.pone.0048477 The Phylogeography of Y-Chromosome Haplogroup H1a1a-M82 Reveals the Likely Indian Origin of the European Romani Populations Niraj Rai1., Gyaneshwer Chaubey2*., Rakesh Tamang1., Ajai Kumar Pathak3, Vipin Kumar Singh1, Monika Karmin2,3, Manvendra Singh1, Deepa Selvi Rani1, Sharath Anugula1, Brijesh Kumar Yadav1, Ashish Singh1, Ramkumar Srinivasagan1, Anita Yadav1, Manju Kashyap1, Sapna Narvariya1, Alla G. Reddy1, George van Driem4., Peter A. Underhill5, Richard Villems2,3,6, Toomas Kivisild3,7, Lalji Singh1,8,9, Kumarasamy Thangaraj1* 1 CSIR-Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology, Uppal Road, Hyderabad, India, 2 Evolutionary Biology -

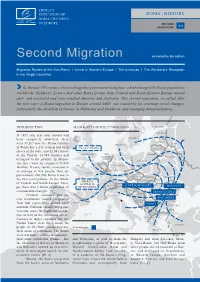

Second Migration Compiled by the Editors

PROJECT EDucaTION OF ROma | HISTORY ROma CHILDREN COUNCIL CONSEIL OF EUROPE DE L´EUROPE IN EuROPE SECOND 4.0 MIGRATION Second Migration compiled by the editors Migration Routes of the Vlax-Roma l Arrival in Western Europe l The Americas l The Wanderers’ Reception in the Target Countries In the mid-19th century, a second migratory movement took place, which changed the Roma population worldwide. Kalderaš, Lovara and other Roma groups from Central and South-Eastern Europe moved east- and westward and even reached America and Australia. This second migration, so-called after the first wave of Roma migration in Europe around 1400, was caused by far-reaching social changes, particularly the abolition of slavery in Wallachia and Moldavia, and emerging industrialisation. INTRODucTION MAIN ROUTES OF THE 2ND MIGRATION Ill. 1 FINLAND EsTONIA In 1857, one year after slavery had been completely abolished, there SWEDEN LaTVIA were 33,267 now free Roma families DENmaRK RUssIA in Wallachia; 6,241 of them had been USA & CANADA LITHuaNIA slaves of the state, and 12,081 slaves of the Church. 14,945 families had ENGLAND THE NETHER- BELARus belonged to the nobility. In Molda- LANDS POLAND via, there were an estimated 20,000 BELGIum GERMANY families. If every family consisted of an average of five people, then ap- LuXEmbOURG FRANCE proximately 250,000 Roma lived in CZECH REPubLIC UKRAINE the two principalities. In the whole amERIca SLOVAKIA of Central and South-Eastern Euro- ausTRALIA SWITZER- AusTRIA-HuNgaRY MOLDAVIA pe, there was a Roma population of SOUTH afRIca LAND considerable strength. SLOVENIA TRANsyLVANIA Political, economic and so- ITALY CROATIA WaLLacHIA cial revolutions caused emigration BOSNIA HERZ.