Politics II.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rulers of Palenque a Beginner’S Guide

The Rulers of Palenque A Beginner’s Guide By Joel Skidmore With illustrations by Merle Greene Robertson Citation: 2008 The Rulers of Palenque: A Beginner’s Guide. Third edition. Mesoweb: www. mesoweb.com/palenque/resources/rulers/PalenqueRulers-03.pdf. Publication history: The first edition of this work, in html format, was published in 2000. The second was published in 2007, when the revised edition of Martin and Grube’s Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens was still in press, and this third conforms to the final publica- tion (Martin and Grube 2008). To check for a more recent edition, see: www.mesoweb.com/palenque/resources/rulers/rulers.html. Copyright notice: All drawings by Merle Greene Robertson unless otherwise noted. Mesoweb Publications The Rulers of Palenque INTRODUCTION The unsung pioneer in the study of Palenque’s dynastic history is Heinrich Berlin, who in three seminal studies (Berlin 1959, 1965, 1968) provided the essential outline of the dynasty and explicitly identified the name glyphs and likely accession dates of the major Early and Late Classic rulers (Stuart 2005:148-149). More prominent and well deserved credit has gone to Linda Schele and Peter Mathews (1974), who summarized the rulers of Palenque’s Late Classic and gave them working names in Ch’ol Mayan (Stuart 2005:149). The present work is partly based on the transcript by Phil Wanyerka of a hieroglyphic workshop presented by Schele and Mathews at the 1993 Maya Meet- ings at Texas (Schele and Mathews 1993). Essential recourse has also been made to the insights and decipherments of David Stuart, who made his first Palenque Round Table presentation in 1978 at the age of twelve (Stuart 1979) and has recently advanced our understanding of Palenque and its rulers immeasurably (Stuart 2005). -

Mexico), a Riverine Settlement in the Usumacinta Region

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE From Movement to Mobility: The Archaeology of Boca Chinikihá (Mexico), a Riverine Settlement in the Usumacinta Region A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology by Nicoletta Maestri June 2018 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Wendy Ashmore, Chairperson Dr. Scott L. Fedick Dr. Karl A. Taube Copyright by Nicoletta Maestri 2018 The Dissertation of Nicoletta Maestri is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation talks about the importance of movement and – curiously enough – it is the result of a journey that started long ago and far away. Throughout this journey, several people, in the US, Mexico and Italy, helped me grow personally and professionally and contributed to this accomplishment. First and foremost, I wish to thank the members of my dissertation committee: Wendy Ashmore, Scott Fedick and Karl Taube. Since I first met Wendy, at a conference in Mexico City in 2005, she became the major advocate of me pursuing a graduate career at UCR. I couldn’t have hoped for a warmer and more engaged and encouraging mentor. Despite the rough start and longer path of my graduate adventure, she never lost faith in me and steadily supported my decisions. Thank you, Wendy, for your guidance and for being a constant inspiration. During my graduate studies and in developing my dissertation research, Scott and Karl offered valuable advice, shared their knowledge on Mesoamerican cultures and peoples and provided a term of reference for rigorous and professional work. Aside from my committee, I especially thank Tom Patterson for his guidance and patience in our “one-to-one” core theory meetings. -

State Interventionism in the Late Classic Maya Palenque Polity: Household and Community Archaeology at El Lacandón

STATE INTERVENTIONISM IN THE LATE CLASSIC MAYA PALENQUE POLITY: HOUSEHOLD AND COMMUNITY ARCHAEOLOGY AT EL LACANDÓN by Roberto López Bravo Licenciado en Arqueología, Escuela Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 1995 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2013 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Roberto Lopez Bravo It was defended on April 18, 2013 and approved by Katheryn M. Linduff Robert D. Drennan Marc Bermann Olivier de Montmollin Dissertation Advisor ii Copyright © by Roberto López Bravo 2013 iii STATE INTERVENTIONISM IN THE LATE CLASSIC MAYA PALENQUE POLITY: HOUSEHOLD AND COMMUNITY ARCHAEOLOGY AT EL LACANDÓN Roberto López Bravo, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2013 Archaeological materials from seven excavated households (three commoner, three elite and a super-elite) from El Lacandón, a rural settlement of the Ancient Maya Palenque polity in Chiapas, Mexico; are analyzed to examine how households and communities were articulated and later affected by incorporation into larger sociopolitical entities. The study spans El Lacandón’s foundation in the Late Preclassic period (300 B.C. -A.D. 150), its abandonment as part of its assimilation into the Palenque polity at the beginning of the Classic period (ca. A.D. 150), and its re-foundation as a 2nd level community in the political hierarchy of the Palenque polity at the end of the Late Classic (A.D. 750-850). Economic analyses consider patterns of production and consumption. -

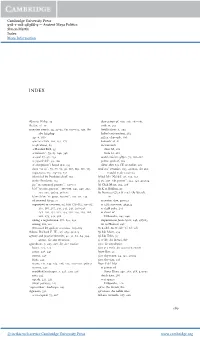

Ancient Maya Politics Simon Martin Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-48388-9 — Ancient Maya Politics Simon Martin Index More Information INDEX Abrams, Philip, 39 destruction of, 200, 258, 282–283 Acalan, 16–17 exile at, 235 accession events, 24, 32–33, 60, 109–115, 140, See fortifications at, 203 also kingship halted construction, 282 age at, 106 influx of people, 330 ajaw as a verb, 110, 252, 275 kaloomte’ at, 81 as ajk’uhuun, 89 monuments as Banded Bird, 95 Altar M, 282 as kaloomte’, 79, 83, 140, 348 Stela 12, 282 as sajal, 87, 98, 259 mutul emblem glyph, 73, 161–162 as yajawk’ahk’, 93, 100 patron gods of, 162 at a hegemon’s home seat, 253 silent after 810 CE or earlier, 281 chum “to sit”, 79, 87, 89, 99, 106, 109, 111, 113 Ahk’utu’ ceramics, 293, 422n22, See also depictions, 113, 114–115, 132 mould-made ceramics identified by Proskouriakoff, 103 Ahkal Mo’ Nahb I, 96, 130, 132 in the Preclassic, 113 aj atz’aam “salt person”, 342, 343, 425n24 joy “to surround, process”, 110–111 Aj Chak Maax, 205, 206 k’al “to raise, present”, 110–111, 243, 249, 252, Aj K’ax Bahlam, 95 252, 273, 406n4, 418n22 Aj Numsaaj Chan K’inich (Aj Wosal), k’am/ch’am “to grasp, receive”, 110–111, 124 171 of ancestral kings, 77 accession date, 408n23 supervised or overseen, 95, 100, 113–115, 113–115, as 35th successor, 404n24 163, 188, 237, 239, 241, 243, 245–246, as child ruler, 245 248–250, 252, 252, 254, 256–259, 263, 266, as client of 268, 273, 352, 388 Dzibanche, 245–246 taking a regnal name, 111, 193, 252 impersonates Juun Ajaw, 246, 417n15 timing, 112, 112 tie to Holmul, 248 witnessed by gods or ancestors, 163–164 Aj Saakil, See K’ahk’ Ti’ Ch’ich’ Adams, Richard E. -

Cuadro Resumen De Pirámides Mayas

Cuadro resumen de pirámides mayas Sitio Edificio Base (m) Altura (m) Referencias Becán IX 50 × 50 31.50 Campaña, 2002: 16. Calakmul II 150 × 130 55 Folan et al., 2001: 31. Calakmul I 100 × 100 50 Folan et al., 2001: 31. Caracol Caaná 120 × 80 43 Martin y Grube, 2000 Chacchoben Templo 1 30 × 30 20 Romero, 2000 Chichén Itzá Castillo 55 × 55 31 Marquina, 1964 Chakanbakán Nohochbalam 60 × 60 42 Cortés, 2000: 100. Cobá Nohoch Mul 60 × 50 42 Benavides, 1981: 52, 54. Cobá Gran Plataforma 125 × 110 30 Benavides, 1981: 60. Cobá La Iglesia 40 × 30 24 Benavide,s 1981: 34. Dzibanché Kinichná 70 × 60 35 Nalda et al., 1999 Dzibanché Templo del Búho 27 × 20 (?) 22 Campaña ,1995 Edzná Edificio de los Cinco Pisos 80 × 80 36.50 Benavides, 2014 Ek Balam Acrópolis 160 × 70 30 Vargas y Castillo, 1999 El Mirador Los Monos 70 × 80 48 Matheny, 1987 El Mirador El Tigre 70 × 70 55 Matheny, 1987 El Mirador La Danta 80 × 80 72 Matheny, 1987 El Tigre Estructura IV 40 × 40 28 Vargas, 2013: 153-154. Ichkabal Edificio 4 110 × 100 45 Balanzario, 2017, comunicación personal Ichkabal Edificio 5 110 × 70 35 Balanzario, 2017, comunicación personal Izamal Kinich Kak Moo 200 × 200 32 Marquina, 1964: 807. Lamanai Templo Elevado (N10-43) 60 × 50 33 Shelby, 2000 Moral Reforma Edificio 14A 25 × 25 20 Cuevas, 2010 Edificio 14B 30 × 30 23.50 Cuevas, 2010 Palenque Inscripciones 60 × 40 33 Marquina, 1964; Ruz, 1973 Tikal Templo IV 88 × 65 m 64.60 Marquina, 1964; Harrison, 1999 Tikal Templo III o del Sacerdote Jaguar 60 × 60 55 Marquina, 1964; Harrison, 1999 Uxmal Adivino 77 × 56 35 Marquina, 1964 Xunantunich Castillo 100 × 100 40 <es.wikipedia.org> Bibliografía Andrews, George F. -

A Glimpse from Edzna's Hieroglyphics

Contributions in New World Archaeology 4: 89–110 A GLIMPSE FROM EDZNA’S hieroglyphics: MIDDLE, Late AND TERMINAL CLASSIC PROCESSES OF Cultural INTERACTION BETWEEN THE SOUTHERN, Northern AND WESTERN LOWLANDS CARLOS PALLÁN GAYOL Instituto Nacional de Antropologia e Historia, Mexico and University of Bonn, Germany Abstract From its advantageous location, Edzna readily interacted with different cultural regions of the lowlands and beyond. After four years of research, a new documentation and decipherment of its large hieroglyphic corpus (including over 32 stelae and two hieroglyphic stairways) has yielded important results, including the definition of a dynastic sequence comprising ten rulers and the 7th century “arrival” of a lady possibly from the Petexbatún region. In addition, further evidence detailing the role that Yuhknoom the Great could have exerted as an “overlord” of Edzna will be discussed, along with formulae of subordination possibly linking Edzna to the vast political orbit of Calakmul. Under such an alliance, Edzna may have raised itself to a “golden age” as a major regional capital within an extended Puuc area. Emic geopolitical models discovered at both Tikal and Altar de los Reyes will be examined, within which Edzna appears to be mentioned along with other great lowland centers. The last part will deal with a series of wars waged against an enemy whose identity is preliminary explored. Such events may have provoked Edzna to plunge into a possible “sculptural-hiatus”, a period ended only by another “arrival”, this time led by an individual whose very name and associated portraiture strongly evoke foreign origins within the western Gulf-coastal plains. -

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title A Study of Classic Maya Rulership Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6pb5g8h2 Author Wright, Mark Alan Publication Date 2011 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE A Study of Classic Maya Rulership A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology by Mark Alan Wright August 2011 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Karl A. Taube, Chairperson Dr. Wendy Ashmore Dr. Stephen D. Houston Copyright by Mark Alan Wright 2011 The Dissertation of Mark Alan Wright is approved: ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ___________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements Countless people have helped bring this work to light through direct feedback, informal conversations, and general moral support. I am greatly indebted to my dissertation committee, Karl Taube, Wendy Ashmore, and Stephen Houston for their patience, wisdom, and guidance throughout this process. Their comments have greatly improved this dissertation; all that is good within the present study is due to them, and any shortcomings in this work are entirely my responsibility. I would also like to thank Thomas Patterson for sitting in on my dissertation defense committee on impossibly short notice. My first introduction to Maya glyphs came by way of a weekend workshop at UCLA led by Bruce Love back when I was still trying to decide what I wanted to be when I grew up. His enthusiasm and knowledge for the Maya forever altered the trajectory of my undergraduate and graduate studies, and I am grateful for the conversations we‘ve had over the ensuing years at conferences and workshops. -

Redalyc.POLITICS in the WESTERN MAYA REGION (II)

Estudios de Cultura Maya ISSN: 0185-2574 [email protected] Centro de Estudios Mayas México BÍRÓ, PÉTER POLITICS IN THE WESTERN MAYA REGION (II): EMBLEM GLYPHS Estudios de Cultura Maya, vol. XXXIX, 2012, pp. 31-66 Centro de Estudios Mayas Distrito Federal, México Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=281323561002 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative POLITICS IN THE WESTERN MAYA REGION (II): EMBLEM GLYPHS PÉTER BÍRÓ Abteilung für Altamerikanistik, Bonn RESUMEN: En una serie de artículos investigo el uso de varias palabras en las inscripciones ma- yas de la época Clásica de la Región Occidental que se conectan con lo que nosotros llamamos “política”. Estas palabras expresan ideas y conceptos que ayudan a entender los matices de las relaciones entre las entidades políticas de las Tierras Bajas Mayas y su organización interna. En este artículo investigo el significado de los glifos emblema. Propongo que originalmente fueron topónimos y después llegaron a ser títulos de origen que indicaron descendencia común de un lugar original. PALABRAS CLAVE: Maya Clásico, epigrafía, vocabulario político, glifos emblema. ABSTRACT: In a series of articles I reflect on the use of various expressions which are connected to what we call the political in the inscriptions of the Classic Maya Western Region. These words express ideas and concepts which help to understand the intricate details of the in- teractions between the political entities and their internal organisations in the Classic Maya Lowlands. -

Universidad De San Carlos De Guatemala Escuela De Historia Carrera De Arqueología

UNIVERSIDAD DE SAN CARLOS DE GUATEMALA ESCUELA DE HISTORIA CARRERA DE ARQUEOLOGÍA “Análisis de artefactos malacológicos provenientes del sitio arqueológico El Zotz, Petén, Guatemala” YENY MYSHELL GUTIÉRREZ CASTILLO Nueva Guatemala de la Asunción, Guatemala, C.A. Julio de 2015 UNIVERSIDAD DE SAN CARLOS DE GUATEMALA ESCUELA DE HISTORIA CARRERA DE ARQUEOLOGÍA “Análisis de artefactos malacológicos provenientes del sitio arqueológico El Zotz, Petén, Guatemala” TESIS Presentada por: YENY MYSHELL GUTIÉRREZ CASTILLO Previo a conferírsele el título de: ARQUEÓLOGA En el grado de LICENCIADA Nueva Guatemala de la Asunción, Guatemala, C.A. Julio de 2015 UNIVERSIDAD DE SAN CARLOS DE GUATEMALA ESCUELA DE HISTORIA AUTORIDADES UNIVERSITARIAS RECTOR: Dr. Carlos Guillermo Alvarado Cerezo SECRETARIO: Dr. Carlos Camey AUTORIDADES DE LAS ESCUELA DE HISTORIA DIRECTOR: Dra. Artemis Torres Valenzuela SECRETARIO: Licda. Olga Pérez CONSEJO DIRECTIVO DIRECTOR: SECRETARIO: Vocal I (Representante Docente): Dra. Tania Sagastume Paiz Vocal II (Representante Docente): Licda. María Laura Lizeth Jiménez Chacón Vocal III (Representante de Graduados): Licda. Zoila Rodríguez Girón Vocal IV: (Representante Estudiantil): Amalia Judith Tzunux Sanic Vocal V: (Representante Estudiantil): Byron Anderson Chivalán ASESOR DE TESIS Mtro. Edwin René Román Ramírez COMITÉ DE TESIS Mtra. Lucía Prado Mtra. Griselda Pérez Robles ―Los autores serán responsables de las opiniones o criterios expresados en su obra‖. Capitulo V, Arto. 11 del Reglamento del Consejo Editorial de la Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala‖ DEDICATORIA A Dios por ser el fundamento y quien guía mi camino a lo largo de la vida y sin quien cada meta propuesta no sería realizada. Infinitas gracias por cada día, por cada oportunidad, gracias por todo. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE a Study of Classic

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE A Study of Classic Maya Rulership A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology by Mark Alan Wright August 2011 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Karl A. Taube, Chairperson Dr. Wendy Ashmore Dr. Stephen D. Houston Copyright by Mark Alan Wright 2011 The Dissertation of Mark Alan Wright is approved: ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ___________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements Countless people have helped bring this work to light through direct feedback, informal conversations, and general moral support. I am greatly indebted to my dissertation committee, Karl Taube, Wendy Ashmore, and Stephen Houston for their patience, wisdom, and guidance throughout this process. Their comments have greatly improved this dissertation; all that is good within the present study is due to them, and any shortcomings in this work are entirely my responsibility. I would also like to thank Thomas Patterson for sitting in on my dissertation defense committee on impossibly short notice. My first introduction to Maya glyphs came by way of a weekend workshop at UCLA led by Bruce Love back when I was still trying to decide what I wanted to be when I grew up. His enthusiasm and knowledge for the Maya forever altered the trajectory of my undergraduate and graduate studies, and I am grateful for the conversations we‘ve had over the ensuing years at conferences and workshops. I have continued to study the glyphs at the Texas Meetings at Austin, where I have met many wonderful people that have helped me along the way. -

The PARI Journal Vol. XVI, No. 4

ThePARIJournal A quarterly publication of the Ancient Cultures Institute Volume XVI, No. 4, Spring 2016 In This Issue: Death Becomes Her: Death Becomes Her: An Analysis of Panel An Analysis of Panel 3, Xunantunich, Belize 3, Xunantunich, Belize CHRISTOPHE HELMKE University of Copenhagen by Christophe Helmke and JAIME J. AWE Jaime Awe Northern Arizona University PAGES 1-14 The hieroglyphic stair discovered at remains the pivotal record of this hiero- • Naranjo remains one of the most impor- glyphic stair, since the monument has suc- The Ocellated tant and most discussed monuments in cumbed to the predation of looters, two Turkey in Maya Maya studies. In part this has to do with panels having disappeared altogether, Thought its unique context as well as its evocative whereas others have been displaced to a narrative. It was in 1905 that the Austrian variety of locations, including the collec- by explorer Teobert Maler documented and tions of the British Museum in London Ana Luisa Izqueirdo y photographed the carved monuments at and those of the Museum of Natural de la Cueva and María the archaeological site of Naranjo in what History in New York and the bodega of Elena Vega Villalobos is now Guatemala. Among these is the the Parque Nacional Tikal in Guatemala PAGES 15–23 hieroglyphic stair, composed of twelve (Graham 1978:107). • panels and three sculptures representing With the advent of decipherment, The Further human crania (Maler 1908:Pl. 24) (Figure Tatiana Proskouriakoff (1993:40-41) and Adventures of Merle 1). During subsequent visits in the suc- Michael Closs (1984:78, Table 1) defined (continued) ceeding years, early epigraphers such as the range of dates of the hieroglyphic stair by Sylvanus G. -

Places of Power and Memory in Mesoamerica's Past and Present

Daniel Graña-Behrens (ed.) Places of Power and Memory in Mesoamerica’s Past and Present How Sites, Toponyms and Landscapes Shape History and Remembrance ESTUDIOS INDIANA 9 Places of Power and Memory in Mesoamerica’s Past and Present How Sites, Toponyms and Landscapes Shape History and Remembrance Daniel Graña-Behrens (ed.) Gebr. Mann Verlag • Berlin 2016 Estudios Indiana e monographs and essay collections in the Estudios Indiana series present the results of research on multiethnic, indigenous, and Afro-American societies and cultures in Latin America, both contemporary and historical. It publishes original contributions from all areas within the study of the Americas, including archaeology, ethnohistory, sociocultural anthropology and linguistic anthropology. e volumes are published in print form and online with free and open access. En la serie Estudios Indiana se publican monografías y compilaciones que representan los resultados de investigaciones sobre las sociedades y culturas multiétnicas, indígenas y afro-americanas de América Latina y el Caribe tanto en el presente como en el pasado. Reúne contribuciones originales de todas las áreas de los estudios americanistas, incluyendo la arqueología, la etnohistoria, la antropología socio-cultural y la antropología lingüística. Los volúmenes se publican en versión impresa y online con acceso abierto y gratuito. Editado por: Ibero-Amerikanisches Institut – Preußischer Kulturbesitz Potsdamer Straße 37 D-10785 Berlin, Alemania e-mail: [email protected] http://www.iai.spk-berlin.de