The PARI Journal Vol. XVI, No. 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Criteria-Based System for the Qualitative Assessment of Reading Proposals for the Deciphering of Classic Mayan Hieroglyphs

Modelling vagueness – A criteria-based system for the qualitative assessment of reading proposals for the deciphering of Classic Mayan hieroglyphs Franziska Diehr1, Sven Gronemeyer2, 3, Elisabeth Wagner2, Christian Prager2, Katja Diederichs2, Uwe Sikora1, Maximilian Brodhun1, Nikolai Grube2 1 State and University Library Göttingen, Germany 2 Department for Anthropology of the Americas, University of Bonn, Germany 3 Department of Archaeology and History, La Trobe University, Australia [email protected] Abstract office, located at the Department for the Anthropo- logy of the Americas, University of Bonn,3 works The project ‘Text Database and Diction- in close collaboration with the State and University ary of Classic Mayan’ aims at creating a Library Göttingen.4 Since 2014, the hieroglyphic machine-readable corpus of all Maya texts texts have been prepared, evaluated, and interpreted and compiling a dictionary on this basis. in interdisciplinary cooperation using methods and The characteristics of this complex writ- tools from the humanities and information techno- ing system pose particular challenges to logy (Prager, 2014c). research, resulting in contradictory and am- One result of this collaboration, and at the same biguous deciphering hypotheses. In this time an important milestone of the project, is the paper, we present a system for the qualitat- digital Sign Catalogue which is the subject of this ive evaluation of reading proposals that is paper. For the creation of a text corpus and a dic- integrated into a digital Sign Catalogue for tionary of an only partially understood language Mayan hieroglyphs, establishing a novel and script, a Sign Catalogue, an inventory of all concept for sign systematisation and clas- used signs, is an indispensable instrument. -

The Rulers of Palenque a Beginner’S Guide

The Rulers of Palenque A Beginner’s Guide By Joel Skidmore With illustrations by Merle Greene Robertson Citation: 2008 The Rulers of Palenque: A Beginner’s Guide. Third edition. Mesoweb: www. mesoweb.com/palenque/resources/rulers/PalenqueRulers-03.pdf. Publication history: The first edition of this work, in html format, was published in 2000. The second was published in 2007, when the revised edition of Martin and Grube’s Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens was still in press, and this third conforms to the final publica- tion (Martin and Grube 2008). To check for a more recent edition, see: www.mesoweb.com/palenque/resources/rulers/rulers.html. Copyright notice: All drawings by Merle Greene Robertson unless otherwise noted. Mesoweb Publications The Rulers of Palenque INTRODUCTION The unsung pioneer in the study of Palenque’s dynastic history is Heinrich Berlin, who in three seminal studies (Berlin 1959, 1965, 1968) provided the essential outline of the dynasty and explicitly identified the name glyphs and likely accession dates of the major Early and Late Classic rulers (Stuart 2005:148-149). More prominent and well deserved credit has gone to Linda Schele and Peter Mathews (1974), who summarized the rulers of Palenque’s Late Classic and gave them working names in Ch’ol Mayan (Stuart 2005:149). The present work is partly based on the transcript by Phil Wanyerka of a hieroglyphic workshop presented by Schele and Mathews at the 1993 Maya Meet- ings at Texas (Schele and Mathews 1993). Essential recourse has also been made to the insights and decipherments of David Stuart, who made his first Palenque Round Table presentation in 1978 at the age of twelve (Stuart 1979) and has recently advanced our understanding of Palenque and its rulers immeasurably (Stuart 2005). -

Mexico), a Riverine Settlement in the Usumacinta Region

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE From Movement to Mobility: The Archaeology of Boca Chinikihá (Mexico), a Riverine Settlement in the Usumacinta Region A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology by Nicoletta Maestri June 2018 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Wendy Ashmore, Chairperson Dr. Scott L. Fedick Dr. Karl A. Taube Copyright by Nicoletta Maestri 2018 The Dissertation of Nicoletta Maestri is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation talks about the importance of movement and – curiously enough – it is the result of a journey that started long ago and far away. Throughout this journey, several people, in the US, Mexico and Italy, helped me grow personally and professionally and contributed to this accomplishment. First and foremost, I wish to thank the members of my dissertation committee: Wendy Ashmore, Scott Fedick and Karl Taube. Since I first met Wendy, at a conference in Mexico City in 2005, she became the major advocate of me pursuing a graduate career at UCR. I couldn’t have hoped for a warmer and more engaged and encouraging mentor. Despite the rough start and longer path of my graduate adventure, she never lost faith in me and steadily supported my decisions. Thank you, Wendy, for your guidance and for being a constant inspiration. During my graduate studies and in developing my dissertation research, Scott and Karl offered valuable advice, shared their knowledge on Mesoamerican cultures and peoples and provided a term of reference for rigorous and professional work. Aside from my committee, I especially thank Tom Patterson for his guidance and patience in our “one-to-one” core theory meetings. -

State Interventionism in the Late Classic Maya Palenque Polity: Household and Community Archaeology at El Lacandón

STATE INTERVENTIONISM IN THE LATE CLASSIC MAYA PALENQUE POLITY: HOUSEHOLD AND COMMUNITY ARCHAEOLOGY AT EL LACANDÓN by Roberto López Bravo Licenciado en Arqueología, Escuela Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 1995 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2013 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Roberto Lopez Bravo It was defended on April 18, 2013 and approved by Katheryn M. Linduff Robert D. Drennan Marc Bermann Olivier de Montmollin Dissertation Advisor ii Copyright © by Roberto López Bravo 2013 iii STATE INTERVENTIONISM IN THE LATE CLASSIC MAYA PALENQUE POLITY: HOUSEHOLD AND COMMUNITY ARCHAEOLOGY AT EL LACANDÓN Roberto López Bravo, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2013 Archaeological materials from seven excavated households (three commoner, three elite and a super-elite) from El Lacandón, a rural settlement of the Ancient Maya Palenque polity in Chiapas, Mexico; are analyzed to examine how households and communities were articulated and later affected by incorporation into larger sociopolitical entities. The study spans El Lacandón’s foundation in the Late Preclassic period (300 B.C. -A.D. 150), its abandonment as part of its assimilation into the Palenque polity at the beginning of the Classic period (ca. A.D. 150), and its re-foundation as a 2nd level community in the political hierarchy of the Palenque polity at the end of the Late Classic (A.D. 750-850). Economic analyses consider patterns of production and consumption. -

Disharmony in Maya Hieroglyphic Writing

FIVE Disharmony in Maya Hieroglyphic Writing Linguistic Change and Continuity in Classic Society Stephen Houston Brigham Young University David Stuart Peabody Museum, Harvard University John Robertson Brigham Young University Some forty-five years ago Yuri Knorozov discovered the existence of phonetic syllables in Maya writing (1952, 1958, 1965, 1967a). Despite strong opposition, Knorozov made an excellent case that Maya script recorded signs of consonant + vowel form. When com- bined in groupings of two or more glyphs these signs spelled words like ma + ma→ mam or ku + tzu→ kutz. In each instance the final vowel of the second syllable—a superfluous, “dead” vowel—could be safely detached once the two syllables were joined into a CVC (or CVCVC) root, the most common configuration in Mayan languages. Knorozov’s in- sight has been discussed elsewhere, either as an issue in intellectual history (Houston 1988; Coe 1992) or as a topic in decipherment (Justeson and Campbell, eds., 1984). To- day, few epigraphers question the singular importance of Knorozov’s contribution. Work- ing in near-total isolation from other Mayanists, he succeeded in achieving a break- through that fundamentally changed modern views of Maya writing. Yet Knorozov could not explain one feature of syllabic signs: What, precisely, deter- mined the final sign in such groupings? Knorozov detected a default arrangement, which he labeled “synharmony,” by which the vowel of the second sign duplicated that of the first (Knorozov 1965: 174–75). As Kelley pointed out, this pattern explained a large num- ber of spellings (Kelley 1976: 18). Lounsbury, too, found that synharmony accorded with morphophonemic processes in Mayan languages (1973: 100), especially the “echo” sylla- ble, a “voiceless . -

Kettunen and Helmke: Introduction to Maya Hieroglyphs

Introduction to Maya Hieroglyphs Workshop Handbook 10th European Maya Conference Leiden, December 5–10, 2005 Harri Kettunen University of Helsinki Christophe Helmke University College London Wayeb & Leiden University Dedicated to the memory of John Montgomery Introduction to Maya Hieroglyphs Harri Kettunen & Christophe Helmke Wayeb & Leiden University 2005 Kettunen & Helmke 2005 Introduction to Maya Hieroglyphs TABLE OF CONTENTS: Foreword ................................................................................................................................................. 4 Acknowledgments................................................................................................................................... 4 Note on the Orthography......................................................................................................................... 5 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 6 2. History of Decipherment.................................................................................................................... 7 3. Origins of the Maya Script ............................................................................................................... 11 4. Language(s) of the Hieroglyphs....................................................................................................... 12 5. Writing System................................................................................................................................ -

Ancient Maya Politics Simon Martin Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-48388-9 — Ancient Maya Politics Simon Martin Index More Information INDEX Abrams, Philip, 39 destruction of, 200, 258, 282–283 Acalan, 16–17 exile at, 235 accession events, 24, 32–33, 60, 109–115, 140, See fortifications at, 203 also kingship halted construction, 282 age at, 106 influx of people, 330 ajaw as a verb, 110, 252, 275 kaloomte’ at, 81 as ajk’uhuun, 89 monuments as Banded Bird, 95 Altar M, 282 as kaloomte’, 79, 83, 140, 348 Stela 12, 282 as sajal, 87, 98, 259 mutul emblem glyph, 73, 161–162 as yajawk’ahk’, 93, 100 patron gods of, 162 at a hegemon’s home seat, 253 silent after 810 CE or earlier, 281 chum “to sit”, 79, 87, 89, 99, 106, 109, 111, 113 Ahk’utu’ ceramics, 293, 422n22, See also depictions, 113, 114–115, 132 mould-made ceramics identified by Proskouriakoff, 103 Ahkal Mo’ Nahb I, 96, 130, 132 in the Preclassic, 113 aj atz’aam “salt person”, 342, 343, 425n24 joy “to surround, process”, 110–111 Aj Chak Maax, 205, 206 k’al “to raise, present”, 110–111, 243, 249, 252, Aj K’ax Bahlam, 95 252, 273, 406n4, 418n22 Aj Numsaaj Chan K’inich (Aj Wosal), k’am/ch’am “to grasp, receive”, 110–111, 124 171 of ancestral kings, 77 accession date, 408n23 supervised or overseen, 95, 100, 113–115, 113–115, as 35th successor, 404n24 163, 188, 237, 239, 241, 243, 245–246, as child ruler, 245 248–250, 252, 252, 254, 256–259, 263, 266, as client of 268, 273, 352, 388 Dzibanche, 245–246 taking a regnal name, 111, 193, 252 impersonates Juun Ajaw, 246, 417n15 timing, 112, 112 tie to Holmul, 248 witnessed by gods or ancestors, 163–164 Aj Saakil, See K’ahk’ Ti’ Ch’ich’ Adams, Richard E. -

Cuadernos De Trabajo 38

Cuadernos de Trabajo Instituto de Investigaciones Histórico-Sociales UNIVERSIDAD VERACRUZANA 38 La Escritura Mesoamericana y Maya Patrimonio Epigráfico de los Mayas La Casa Knorosov Xcaret Dr. Pedro Jiménez Lara Xalapa, Veracruz Noviembre de 2010 INSTITUTO DE INVESTIGACIONES HISTÓRICO-SOCIALES Director: Martín Aguilar Sánchez CUADERNOS DE TRABAJO Editor: Feliciano García Aguirre Comité Editorial: Joaquín R. González Martinez Rosío Córdova Plaza Pedro Jiménez Lara David Skerritt Gardner CUADERNO DE TRABAJO N° 38 © Instituto de Investigaciones Histórico-Sociales Universidad Veracruzana Diego Leño 8, Centro Xalapa, C.P. 91000, Veracruz ISSN 1405-5600 Viñeta de la portada: Luis Rechy (†) Cuidado de la edición: Lilia del Carmen Cárdenas Vázquez La Escritura Mesoamericana y Maya Patrimonio Epigráfico de los Mayas La Casa Knorosov Xcaret Dr. Pedro Jiménez Lara Cuadernos de trabajo Instituto de Investigaciones Histórico-Sociales Universidad Veracruzana Indice Página Introducción 6 Yuri Valentinovich Knorosov Desciframiento de la Escritura Maya 9 Sus primeros estudios 9 Un epigrafista rojo 10 En tierras mayas previo a su último viaje 11 Knorosov un cientifico completo 11 Proyecto para la escritura mesoamericana y maya 16 Socios Fundadores 29 Universidad Estatal de Rusia de Ciencias Humanas de Moscu Facultad de Historia, Politología y Derecho: Centro de Estudios Mesoamericanos “Yuri knórosov” (Moscú) 29 Universidad Veracruzana 31 Instituto de Investigaciones Histórico-Sociales 33 Centro turistico Kcaret 34 Conclusiones 37 Bibliografía 38 Anexo 1. Protocolo de intenciones entre Universidad Estatal de Rusia de Ciencias Humanas (Federación de Rusia) y Universidad Veracruzana, Xalapa (México) 39 “Cualquier sistema o código elaborado por un ser humano podría ser resuelto por cualquier otro ser humano” Knorosov, Moscú, 1952 Introducción Una de las creaciones, por excelencia, hecha por el hombre es sin lugar a dudas la escritura como medio comunicación y de dejar evidencia de su existencia. -

Semble-T-Il, La Posture Fondamentale Des Auteurs Devant Geminoïd, C'est

Rezensionen 285 semble-t-il, la posture fondamentale des auteurs devant uscript). The book also features a brief introduction by Geminoïd, c’est-à-dire une posture qui évacue presque Nikolai Grube on the basics of Maya hieroglyphic writ- complètement le sens critique. Les auteurs veulent croire ing, mathematics, calendar, and religion, as well as the dans la possibilité d’établir une communication avec Ge- structure and content of the codex. Another short article minoïd, et cette croyance est au fondement de la surin- by Thomas Bürger outlines the history of the manuscript. terprétation. Ils parlent bien de “résistance au simulacre” Photographs are of high quality and constitute the first (158), mais ils y résistent très peu, ou seulement spora- accurate reproduction of the Codex, which was meticu- diquement. Comme ils le disent, ils se laissent prendre lously restored after it had suffered serious damage during au jeu (40). the firebombing of Dresden in World War II. As the qual- Les conclusions des auteurs au sujet de la communi- ity of photographic reproductions and facsimiles before cation sont somme toute assez triviales. Il est en effet dif- World War II cannot be compared with modern reproduc- ficile de communiquer avec une machine, même quand tions, it is not just a nicely illustrated edition for people on a la croyance. “Deux modes d’existence entrent ici en who want to learn about the Maya, but also an invaluable friction, l’organique et le machinique. Ils s’affrontent sans source for Mayanists. The whole codex is also now online possibilité de s’unir, de se combiner, dans une nouvelle in high resolution. -

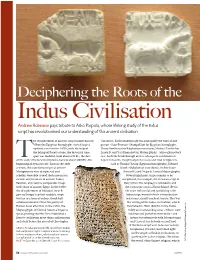

Deciphering the Roots Of

Deciphering the Roots of the Indus Civilisation Andrew Robinson pays tribute to Asko Parpola, whose lifelong study of the Indus script has revolutionised our understanding of this ancient civilisation. he decipherment of ancient scripts makes history. Columbus. Each breakthrough was principally the work of one When the Egyptian hieroglyphs started to give person – Jean-François Champollion for Egyptian hieroglyphs, up their secrets in the 1820s, with the help of Henry Rawlinson for Babylonian cuneiform, Michael Ventris for the bilingual Rosetta stone, the historical time Linear B, and Yuri KnoroZov for Mayan glyphs – although in every span was doubled, from about 600 BC, the date case, both the breakthrough and its subsequent confirmation ofT the earliest Hebrew inscriptions, back to about 3000 BC, the depended on the insights of predecessors and rival decipherers, beginning of dynastic rule. Later in the 19th such as Thomas Young (Egyptian hieroglyphs), Edward century, the cuneiform scripts of ancient Hincks (Babylonian cuneiform), Arthur Evans Mesopotamia were deciphered; and (Linear B), and Diego de Landa (Mayan glyphs). scholars were able to read the bureaucratic Several significant scripts remain to be records and literature of ancient Sumer, deciphered, for example, the Etruscan script of Babylon, and Assyria, comparable in age Italy (where the language is unknown) and with those of ancient Egypt. In the 1950s, the rongorongo script of Easter Island. By far the decipherment of Minoan Linear B the most influential and tantalising is the gave us Europe’s earliest readable script, Indus script, most of which is inscribed on written in a form of archaic Greek half seal stones, chiefly made of steatite. -

La Península Ibérica

Los mayas Chichen Itza Yucatan Tikal Guatemala Mapa Maya Según Carlos A. Loprete. Iberoamérica: historia de su civilización y cultura. (4ª ed. Prentice Hall, 2001). Capítulo 2 (Outline) Los mayas. ¿Su origen? Un misterio. Probablemente, durante muchos años o siglos llevaron una vida nómada, en busca de una region propia, hasta que se asentaron en la región de las actuales Yucatán (México), Guatemala, parte de Honduras y El Salvador. Es probable que recorrieran tierras muy frías y muy cálidas y que el descubrimiento del maíz en la zona les diera la oportunidad de quedarse allí y dedicarse a su cultivo. El pueblo maya contó con excelentes artistas, hombres de ciencia, astronómicos y arquitectos. Es posible que por el refinamiento estético de su arte y arquitectura, la precisión de su sistema astronómico, la complejidad de sus calendarios y el desarrollo de su matemática y escritura, no hayan sido superados por ninguna otra civilización del Nuevo Mundo y apenas igualados por muy pocas del Viejo Mundo. Están considerados como “los griegos” de América. Los mayas se establecieron en Centroamérica hacia los años 2000 o 1500 antes de Jesucristo. Durante varios siglos vivieron en un estado de formación cultural, hasta que, aproximadamente en el año 300 d.C., lograron las características esenciales de su civilización, en la región denominada El Petén, en el norte de Guatemala. Esta civilización estuvo integrada por numerosas ciudades-estados, que hablaban una lengua común, aunque con ligeras variantes dialectales, y tenían similares rasgos culturales. Sin embargo, no parecen haber tenido una unidad política ni una ciudad capital. En distintas etapas, fueron levantando grandes ciudades: Tikal (la más Antigua y la mayor) y Uaxactún, en Guatemala; Chichén-Itzá (abandonada y reconstruida tres veces) y Palenque, en México; y Copán, en Honduras. -

Russia in Global Affairs July

RUSSIA in GLOBAL AFFAIRS Vol. 4•No. 3•JULY – SEPTEMBER•2006 Contents The Russian Season Fyodor Lukyanov 5 Russia in Focus Russia’s G8 History: From Guest to President Vadim Lukov 8 Russia’s participation in the G8 has provided the group with a major incen- tive for confronting a broad range of international political problems involv- ing strategic stability, regional conflicts and nonproliferation. The expansion of summit agendas has given “fresh oxygen” to the dialog between the G8 leaders. The Kremlin at the G8’s Helm: Choosing the Right Steps Vlad Ivanenko 22 Chairing the G8 meeting in St. Petersburg is an important test of the Kremlin administration’s ability to advance its national interests abroad. If Russia engages other members in a substantive discussion of its proposals, it will make a significant accomplishment. Comments by Hiski Haukkala and Peter Rutland. Russia, an Engine for Global Development Fyodor Shelov-Kovedyaev 36 Russia should cease playing a game of “catch up” with the so-called devel- oped economies, as well as relinquish the idea of antagonism between Russian and Western interests. Russia and the West objectively need each other. Contents The Russian Economy Today and Tomorrow Arkady Dvorkovich 46 While the problems that Russia must solve in the next three years are quite serious, the long-term challenges are much more fundamental. These chal- lenges include the reduction of the Russian population; the decline in the skill level of manpower resources; the aging of the infrastructure; and the need for sufficient competitive niches in the global division of labor. Foreign Policy Imperatives Asia’s Future and Russia’s Policy Situation Analysis 56 The formation of Russia’s new policy toward the Asia-Pacific countries is impossible without transforming its foreign-policy thinking, which has been traditionally focused on the Euro-Atlantic space.