Beyond the Pavement RTA Urban Design Policy, Procedures and Design Principles Eastern Distributor, Sydney CONTENTS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Graham Clifton Southwell

Graham Clifton Southwell A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts (Research) Department of Art History Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences University of Sydney 2018 Bronze Southern Doors of the Mitchell Library, Sydney A Hidden Artistic, Literary and Symbolic Treasure Table of Contents Abstract Acknowledgements Chapter One: Introduction and Literature Review Chapter Two: The Invention of Printing in Europe and Printers’ Marks Chapter Three: Mitchell Library Building 1906 until 1987 Chapter Four: Construction of the Bronze Southern Entrance Doors Chapter Five: Conclusion Bibliography i! Abstract Title: Bronze Southern Doors of the Mitchell Library, Sydney. The building of the major part of the Mitchell Library (1939 - 1942) resulted in four pairs of bronze entrance doors, three on the northern facade and one on the southern facade. The three pairs on the northern facade of the library are obvious to everyone entering the library from Shakespeare Place and are well documented. However very little has been written on the pair on the southern facade apart from brief mentions in two books of the State Library buildings, so few people know of their existence. Sadly the excellent bronze doors on the southern facade of the library cannot readily be opened and are largely hidden from view due to the 1987 construction of the Glass House skylight between the newly built main wing of the State Library of New South Wales and the Mitchell Library. These doors consist of six square panels featuring bas-reliefs of different early printers’ marks and two rectangular panels at the bottom with New South Wales wildflowers. -

Phillips, Michael

Australian Earthquake Engineering Society 2013 Conference, Nov 15-17 2013, Hobart, Tas Measuring Bridge Characteristics to Predict their Response in Earthquakes Michael Phillips1 and Kevin McCue2 1. EPSO Seismic, PO Box 398, Coonabarabran, NSW 2357. Email: [email protected] 2. Adjunct Professor, Central Queensland University, Rockhampton, Qld 4701. Email: [email protected] Abstract During 2011 and 2012 we measured the response of the Sydney Harbour Bridge (SHB) to ambient vibration, and determined the natural frequencies and damping of various low-order resonance modes. These measurements were conducted using a simple triaxial MEMS acceleration sensor located at the mid-point of the road deck. The effectiveness of these measurements suggested that a full mapping of modal amplitudes along the road deck could be achieved by making many incremental measurements along the deck, then using software to integrate these data. To accommodate the briefer spot-measurements required, improved recording equipment was acquired, resulting in much improved data quality. Plotting the SHB deck motion data with 3D graphics nicely presents the modal amplitude characteristics of various low order modes, and this analysis technique was then applied to a more complex bridge structure, namely the road deck of Sydney’s Cahill Expressway Viaduct. Unlike the single span of the SHB, the Cahill Expressway Viaduct (CHE) dramatically changes its modal behavior along its length, and our analysis system highlights a short section of this elevated roadway that is seismically vulnerable. On the basis of these observations, the NSW Roads & Maritime Services (RMS) indicated that they will conduct an investigation into the structure at this location. -

Sydney Harbour Bridge Footpath and Cycleway Waterproofing Trial

Union Street LAVENDER BAY High Street Sydney Harbour Bridge Footpath water proong trial E l am a During night work, Burton Street ng A 5 venue McMAHONS pedestrians will be directed 4 MILSONS POINT Glenn Street Bligh Street by sta from the pedestrian POINT STATION Fitzroy Street path (5) to the cycleway (4) Y L Work Trial Alfred Street South N O Location S T Point Road S I L C Y Jeffrey Street Jeffrey Blues KIRRIBILLI C Kirribilli Avenue NORTH SYDNEY Street Broughton OLYMPIC POOL AND LUNA PARK rive D ic p m y l O Port Jackson During night work, pedestrians will be directed Sydney Harbour Bridge PEDESTRIANS ONLY by sta from the pedestrian Sydney Harbour Tunnel path (3) to the cycleway (2) DAWES POINT PARK Road BENNELONG POINT CAMPBELLS Hickson Road Hickson COVE THE Windmill Street ROCKS Lower Fort Street Argyle Street OBSERVATORY Cumberland Street PARK 2 CIRCULAR 3 Circular Quay West QUAY Street George Street CIRCULAR GOVERNMENT Kent Street 1 QUAY HOUSE STATION Macquarie Street Upper Fort Street Circular Quay East Harrington Highway Cahill Expressway ROYAL Bradfield BOTANIC GARDENS LEGEND Grosvenor Street 1 Cumberland Street, The Rocks. Bridge Street Circular Quay to Sydney Harbour Bridge pedestrian Pedestrian access to the Sydney Harbour Bridge access via Cahill Expressway. Wheelchair access to via the Cahill Walkway and Bridge Stairs. and from Circular Quay Station by lift. Phillip Street THE 2 Upper Fort Street, Millers Point. Sydney Harbour Bridge pedestrian access. This access Main access point for cyclists on the southern side of the Sydney will be closed forDOMAIN the trial. -

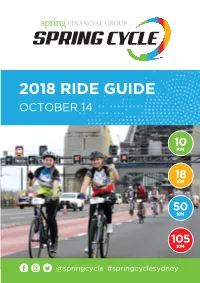

2018 Ride Guide October 14

2018 RIDE GUIDE OCTOBER 14 10 KM 18 KM 50 KM 105 KM @springcycle #springcyclesydney TAKE THE ROAD TO YOUR FINANCIAL FUTURE. The best way to get where you want to go in life is to plan the journey. At Spring Financial Group, we’ll help you navigate the road ahead and make the most of your financial future. We offer a fresh approach by providing tailored financial advice that is affordable, and would like to extend an invitation for you to come in and talk with us on a confidential and obligation free basis. Call 02 9248 0422 to arrange a meeting or visit springFG.com CONTENTS 2018 Spring Financial Group Spring Cycle 4 Get More With a Bicycle NSW Membership! 7 Ride Day Ready 9 Getting There 16 Road Closures 20 Rider Support 22 Festival Finish – What’s On 24 Spring Cycle Ambassador 25 Make Your Ride Count – Fundraise 27 Getting Home 29 For Your Safety 30 Cycling Etiquette 32 Sydney Olympic Park Finish Map 35 Pyrmont Finish Map 36 Sponsors 40 3 WELCOME TO THE 2018 SPRING FINANCIAL GROUP SPRING CYCLE Bicycle NSW along with Fairfax Events & Entertainment is pleased to present the 2018 Spring Financial Group Spring Cycle. This Ride Guide contains important information to help you make the most of Spring Cycle on Sunday October 14. Bicycle NSW want as many people as possible in New South Wales to experience the thrill of riding over the Sydney Harbour Bridge and past some of Sydney’s most iconic landmarks. Spring Cycle is a day we can celebrate cycling and rediscover its joys by riding through Sydney and beyond on roads, paths and through parks you may never have crossed before. -

New South Wales Class 1 Agricultural Vehicles (Notice) 2015 (No

Commonwealth of Australia Gazette Published by the Commonwealth of Australia GOVERNMENT NOTICES HEAVY VEHICLE NATIONAL LAW New South Wales Class 1 Agricultural Vehicles (Notice) 2015 (No. 1) This notice revokes the Class 1 Agricultural Vehicles Notice 2014 published in the New South Wales Government Gazette No. 15 of 7 February 2014, at page 426 to 459 and replaces it with Schedule 1. 1 Purpose (1) The purpose of this notice is to exempt the stated categories of class 1 heavy vehicles from the prescribed mass and dimension requirements specified in the notice subject to the conditions specified in the notice. 2 Authorising Provision(s) (1) This notice is made under Section 117, and Section 23 of Schedule 1, of the Heavy Vehicle National Law as in force in each participating jurisdiction. 3 Title (1) This notice may be cited as the New South Wales Class 1 Agricultural Vehicles (Notice) 2015 (No. 1) 4 Period of operation (1) This notice commences on the date of its publication in the Commonwealth Gazette and is in force for a period of five years from and including the date of commencement. 5 Definitions and interpretation (1) In this Instrument— (a) any reference to a provision of, or term used in, the former legislation, is to be taken to be a reference to the corresponding provision of, or nearest equivalent term used in, the Heavy Vehicle National Law; and (b) former legislation, means the Road Transport (Mass, Loading and Access) Regulation 2005 (NSW) and the Road Transport (Vehicle and Driver Management) Act 2005 (NSW); and (c) National Regulation means the Heavy Vehicle (Mass, Dimension and Loading) National Regulation. -

New South Wales from 1810 to 1821

Attraction information Sydney..................................................................................................................................................................................2 Sydney - St. Mary’s Cathedral ..............................................................................................................................................3 Sydney - Mrs Macquarie’s Chair ..........................................................................................................................................4 Sydney - Hyde Park ..............................................................................................................................................................5 Sydney - Darling Harbour .....................................................................................................................................................7 Sydney - Opera House .........................................................................................................................................................8 Sydney - Botanic Gardens ................................................................................................................................................. 10 Sydney - Sydney Harbour Bridge ...................................................................................................................................... 11 Sydney - The Rocks .......................................................................................................................................................... -

Macquarie Street and East Circular Quay Sydney New Year's Eve

December 2018 2018 Sydney New Year’s Eve – Macquarie Street and East Circular Quay Sydney New Year’s Eve attracts over a million people to Sydney Harbour and more than one billion people across the globe. Getting in and out of the city is different on New Year’s Eve. There will be road closures, on-street fencing and diversions to help people get around safely. Changed parking conditions Once a road is closed, you, your guests, or suppliers / contractors will not be able to gain access to or exit from car parks and loading docks. Sections of Macquarie Street will be closed from as early as 4am on the morning of New Year’s Eve. It is an offence to drive on closed roads, even from car parks. Plan your movements ahead of time. Special event clearway parking restrictions These will be in place on Macquarie Street, Circular Quay and throughout the Sydney CBD early on New Year’s Eve until New Year’s Day. Clearways are strict ‘no-parking’ zones, even for local residents and mobility scheme permit holders. Vehicles in clearways will be towed and a fee will apply. Special event clearways will be in effect from: 2am on New Year’s Eve to 4am on New Year’s Day on Macquarie Street between Bridge Street and the Opera House roundabout (both sides). 6am on New Year’s Eve to 4am on New Year’s Day on roads through East Circular Quay and remainder of the Sydney CBD. Look for the bright yellow signs and read them carefully when parking, particularly on the night before. -

Report to General Manager

Item 4.5 - Traffic - 24/07/15 NORTH SYDNEY COUNCIL To the General Manager Attach: 1. TMP SUBJECT: (4.4) 2015 Sydney Running Festival - Traffic Management Plan AUTHOR: Report of Manager Traffic and Transport Operations, Michaela Kemp DESCRIPTION/SUBJECT MATTER: Events & Sports Australia has submitted an application for the annual Blackmore’s Sydney Running Festival to be held on Sunday 20th September 2015. The event comprises four different courses with similar routes to last year’s event. The North Sydney leg for each course will start from Bradfield Park via Alfred Street, Middlemiss Street, Arthur Street Tunnel/ Lavender Street and Pacific Highway to the Harbour Bridge. Road closures between 4am and 11am and special event clearways between 1am and 10am in areas of Milsons Point, Lavender Bay and Kirribilli are proposed on the day. These will be implemented under Police and RMS control. The applicant has also provided Traffic Control Plans for pedestrian management between Milsons Point Train Station and the event marshalling area in Bradfield Park. The plans include water-filled and crowd control barriers on the western side of Ennis Road and Broughton Street, closure of the exit on the western side of Milsons Point Train Station in liaison with Sydney Trains, and a reduced temporary 40 km/h speed limit for Broughton Street during the event. Speed limit authorisations require approval from RMS. Standard or Guideline Used: RMS Traffic Control for Work Sites, AS 1742.3; RMS Special Events Guide Signs & Lines Priority: N/A Precinct and Ward: Various, Victoria Impact on Bicycles: Bicycle access to be managed under traffic control as outlined in plans Impact on Pedestrians: Impacts as outlined in plans Impact on Parking: Clearways to be imposed in some areas, as outlined in plans RECOMMENDATION: 1. -

Item 4.7 - Traffic - 6/9/13

Item 4.7 - Traffic - 6/9/13 NORTH SYDNEY COUNCIL To the General Manager Attach TMP SUBJECT: (4.7) 2013 Spring Cycle AUTHOR: Report of Traffic & Transport Engineer, Michaela Kemp DESCRIPTION/SUBJECT MATTER: An application has been received on behalf of Bicycle NSW for the annual Spring Cycle event which is to be held on Sunday 20th October 2013. As in previous years the North Sydney section of the event will start from St Leonards Park in North Sydney to the Harbour Bridge. The courses then continue to Pyrmont and Sydney Olympic Park. Temporary road closures are proposed along Miller Street, Berry Street, Arthur Street, Mount Street and Cahill Expressway, from between 4.00am to 9.30am similar to previous years’ events. Road closures will be implemented by the RMS and/or NSW Police. The applicant has submitted the Draft 2013 Traffic Management Plan. No major route changes in the North Sydney area are proposed and will be similar to previous years’ events. Standard or Guideline Used: AS 1742.3, RMS’s Traffic Control at Work Sites, RMS’s Special Events Guide Signs & Lines Priority: N/A Precinct and Ward: Various, Victoria & Tunks Impact on Bicycles: Impacts as outlined in the report Impact on Pedestrians: Impacts as outlined in the report RECOMMENDATION: THAT Council raises no objection to the Sydney Spring Cycle event to be held on Sunday 20th October 2013, subject to Police and RMS approval, appropriate public liability insurance, and the event being carried out in accordance with AS 1742.3 and 2013 Traffic Management Plan. 2013 Spring Cycle DRAFT TRAFFIC MANAGEMENT PLAN as at August 2013 Traffic Management Plan Contents 1. -

NSW State Budget 2021/22

NSW State Budget 2021/22 Overview The New South Wales State Budget was handed down on Tuesday 22 June by New South Wales Treasurer Dominic Perrottet, his fifth Budget since becoming Treasurer in January 2017. The State deficit is projected to be $8.6 billion in the 2021/22 financial year. Deficits are forecast to remain over the forward estimates. However, a forecasted return to surplus is expected in 2024/2025. State net debt will increase to 6.3 percent of GSP and is expected to reach 13.7% in 2024/25. Treasury expects unemployment will average 5.25 per cent in 2021/22. The summary below provides an overview of the Budget measures: State Development and Resilience • $1.1 billion for Infrastructure NSW supporting major infrastructure • $789.1 million for Resilience NSW coordinating and overseeing disaster management, disaster recovery and building community resilience to future disasters across New South Wales. Funding includes: o $370.2 million in disaster relief through the 2021 NSW Storm and Flood Recovery package o $16.5 million as part of a $268.2 million Stage 2 response to the NSW Bushfire Inquiry, for the establishment of a Bushfire and Natural Hazards Research and Technology Program • $416.1 million for Investment NSW, including: • $35.0 million implementing initiatives under the Entrepreneurship and Innovation Ecosystem government action plan • $11.0 million for two research initiatives aligned with the State’s 2021 Accelerating Research and Development Action Plan: o Emerging Industry Infrastructure Fund to encourage co-investment -

Weekend Shutdown of Cahill Expressway from 8Pm Friday 31 July to 5Am Monday 3 August

Weekend shutdown of Cahill Expressway from 8pm Friday 31 July to 5am Monday 3 August As part of the Northern Toll Plaza Precinct How will the work affect you? Upgrade, Transport for NSW will close the Cahill Expressway to motorists from 8pm During the weekend closure we will work Friday 31 July to 5am Monday 3 August continuously 2020. The bus lane will remain open for Our work might be noisy at times but we will buses and taxis during the day. do everything we can to reduce its impact, During this closure we will remove the toll including carrying out noisier work during the booths and office. day where possible. Investigations that involve digging into the We will also lessen the impacts by using road surface will also be done on the Sydney equipment fitted with noise reduction devices Harbour Bridge. where possible and will carry out noise monitoring at night. Northern toll plaza precinct, looking south towards Sydney Harbour Bridge Transport for NSW 1 Temporary detours and traffic A lane will be open for buses so they can operate from 10am to 7pm on Saturday and advice Sunday. To create a safe work zone, changes to traffic will occur during this weekend closure. A safe work zone will also be in place on Ennis Road Milsons Point, with pedestrian The Cahill Expressway (lanes 7 and 8 of the and vehicle access changes from 9pm Friday bridge) will be closed at High Street Kirribilli to 9am Saturday and 9pm Saturday to 9am and motorists will be encouraged to use the Sunday. -

Yallamundi Rooms Technical and Production Information

Sydney Opera House Yallamundi Rooms Technical and Production Information Yallamundi Rooms Technical and Production Information May 2019 sydneyoperahouse.com Street Address: Mailing Address: Sydney Opera House Sydney Opera House Bennelong Point GPO Box 4274 2 Macquarie St Sydney NSW 2001 Sydney NSW 2000 Australia Australia Venue Bookings: Functions Sales Team T +61 2 9250 7070 [email protected] The information contained in this document is given in good faith and is believed to be correct. All measurements are approximate and should be checked on site. While every effort is made to fulfil production requirements from in-house stock, no guarantee is made that the equipment listed will be available for a particular event. Availability is subject to the requirements of the other Opera House venues. Sydney Opera House Sydney Opera House Yallamundi Rooms Technical and Production Information Page 2 of 23 June 2019 Contents Introduction _____________________________________________________________ 5 Yallamundi Rooms General Information ______________________________________ 6 Accessibility .................................................................................................................................... 7 Hearing Augmentation System ...................................................................................................... 7 Venue Limitations ........................................................................................................................... 7 Furniture ........................................................................................................................................