A Case Study: Prospect Reservoir at Western Sydney

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Professionals Australia's Response on Behalf of Members in Relation to The

Professionals Australia’s response on behalf of members in relation to the proposed restructure PA met with engineers who work in the Engineering Division on two occasions at WNSW Parramatta offices with members dialling-in from regional NSW. PA encouraged members to put forward their professional views on the proposed restructure on whether it addressed existing problems. PA has received some very detailed responses from our members. It is clear there is a high level of concern that the restructure will have undesired impacts on both employees and the functions of Engineering. Many members have taken the opportunity to respond directly to the WNSW email address set up for feedback. This submission does not repeat those comments. This submission is concerned with the first order issue – Does the restructure enhance the undertaking of engineering functions by WaterNSW or not? The next level of concerns which appear to be the main focus of the input provided via the WNSW email are the detail of position descriptions and the arrangements for filling the structure. We understand such matters have also attracted a large number of comments and concerns from members. However, those issues arise only when the first order issue is satisfied. The focus of this submission is whether the restructure has accurately identified the deficiencies and whether the proposal will address those deficiencies. What can a restructure address? A restructure can address issues such as resourcing levels, specific function focus and functional alignment. It cannot address issues caused by dysfunctional organisational behaviour, lack of effective processes, etc. Does the restructure enhance engineering functions at WNSW? The view of WNSW engineers is that overall the restructure will not result in the enhanced performance of the engineering functions required by WNSW. -

October 2010

1 ASHET News October 2010 Volume 3, number 4 ASHET News October 2010 Newsletter of the Australian Society for History of Engineering and Technology th Reservoir, was approved in 1938 and completed in 1940. Preliminary University of Queensland’s 100 geological work for a dam on the Warragamba finally commenced in Anniversary 1942. A dam site was selected in 1946. The University of Queensland and its engineering school are celebrating Building the dam their 100th anniversary this year. Naming the members of the first Senate Excavation work on the Warragamba Dam started in 1948 and actual in the Government Gazette of 16 April 1910 marked the foundation of the construction of the dam began in 1950. It was completed in 1960. It was University. It was Australia’s fifth university. built as a conventional mass concrete dam, 142 metres high and 104 The University’s foundation professor of engineering was Alexander metres thick at the base. For the first time in Australia, special measures James Gibson, Born in London in 1876, he was educated at Dulwich were taken to reduce the effects of heat generated during setting of the College and served an apprenticeship with the Thames Ironworks, concrete; special low-heat cement was used, ice was added to the concrete Shipbuilding and Engineering Company. He became an Assocaite during mixing, and chilled water was circulated through embedded pipes Member of the Institution of Civil Engineers in 1899. He migrated to during setting of the concrete. Shanghai in that year, and came to Sydney in 1900, where he became a The dam was designed to pass a maximum flow of 10,000 cubic fitter at Mort’s Dock. -

Sydney Water in 1788 Was the Little Stream That Wound Its Way from Near a Day Tour of the Water Supply Hyde Park Through the Centre of the Town Into Sydney Cove

In the beginning Sydney’s first water supply from the time of its settlement Sydney Water in 1788 was the little stream that wound its way from near A day tour of the water supply Hyde Park through the centre of the town into Sydney Cove. It became known as the Tank Stream. By 1811 it dams south of Sydney was hardly fit for drinking. Water was then drawn from wells or carted from a creek running into Rushcutter’s Bay. The Tank Stream was still the main water supply until 1826. In this whole-day tour by car you will see the major dams, canals and pipelines that provide water to Sydney. Some of these works still in use were built around 1880. The round trip tour from Sydney is around 350 km., all on good roads and motorway. The tour is through attractive countryside south Engines at Botany Pumping Station (demolished) of Sydney, and there are good picnic areas and playgrounds at the dam sites. source of supply. In 1854 work started on the Botany Swamps Scheme, which began to deliver water in 1858. The Scheme included a series of dams feeding a pumping station near the present Sydney Airport. A few fragments of the pumping station building remain and can be seen Tank stream in 1840, from a water-colour by beside General Holmes Drive. Water was pumped to two J. Skinner Prout reservoirs, at Crown Street (still in use) and Paddington (not in use though its remains still exist). The ponds known as Lachlan Swamp (now Centennial Park) only 3 km. -

Draft Cumberland Community Wellbeing Report 2020 Aacknowledgementcknowledgement Ooff Ccountryountry

CUMBERLAND CITY COUNCIL Draft Cumberland Community Wellbeing Report 2020 AAcknowledgementcknowledgement ooff CCountryountry Cumberland City Council acknowledges the Darug Nation and People as Traditional Custodians of the land on which Cumberland City is situated and pays respect to Aboriginal Elders both past, present and future. We acknowledge Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples as the First Peoples of Australia. Cumberland City Council acknowledges other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples living in the Cumberland Local Government Area and reaffirms that we will work closely with all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities to advance reconciliation within the area. 2 DRAFT CUMBERLAND COMMUNITY WELLBEING REPORT Contents Introduction 4 Transport 8 Education 12 Health 16 Recreation 20 Environment 24 Emergency Services and Justice 28 Monitoring Progress 31 DRAFT CUMBERLAND COMMUNITY WELLBEING REPORT 3 Cumberland City Structure Plan Introduction TOONGABBIE TThehe ‘‘DraftDraft CCumberlandumberland CCommunityommunity WWellbeingellbeing PENDLE HILL RReporteport 22020020 ooutlinesutlines CCouncil’souncil’s kkeyey pprioritiesriorities Great Western Hwy WENTWORTHVILLE ttoo iimprovemprove hhealthealth aandnd wwellbeingellbeing ooutcomesutcomes ttoo M4 Smart Motorway enableenable rresidentsesidents ttoo lliveive rrewarding,ewarding, hhealthyealthy aandnd ssociallyocially cconnectedonnected llives.ives. PROSPECT HILL PEMULWUY Cumberland is experiencing strong population growth. dnalrebmuC ywH MAR-RONG Whilst this growth -

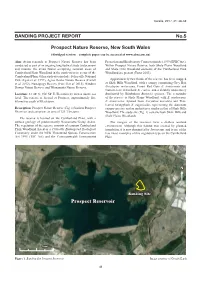

BANDING PROJECT REPORT No.5 Prospect Nature Reserve, New

Corella, 2017, 41: 48-52 BANDING PROJECT REPORT No.5 Prospect Nature Reserve, New South Wales (Abridged version – complete paper can be accessed at www.absa.asn.au) Aim: Avian research at Prospect Nature Reserve has been Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act). conducted as part of an ongoing longitudinal study to document Within Prospect Nature Reserve, both Shale Plains Woodland and monitor the avian faunas occupying remnant areas of and Shale Hills Woodland elements of the Cumberland Plain Cumberland Plain Woodland in the north-western sector of the Woodland are present (Tozer 2003). Cumberland Plain. Other study sites include: Scheyville National Park (Egan et al. 1997), Agnes Banks Nature Reserve (Farrell Approximately two-thirds of the reserve has been mapped et al. 2012), Nurragingy Reserve (Farrell et al. 2015), Windsor as Shale Hills Woodland, with a canopy comprising Grey Box Downs Nature Reserve and Wianamatta Nature Reserve. Eucalyptus moluccana, Forest Red Gum E. tereticornis and Narrow-leaved Ironbark E. crebra, and a shrubby understorey Location: 33° 48′ S; 150° 54′ E. Elevation 61 metres above sea dominated by Blackthorn Bursaria spinosa. The remainder level. The reserve is located at Prospect, approximately five of the reserve is Shale Plains Woodland, with E. moluccana, kilometres south of Blacktown. E. tereticornis, Spotted Gum Corymbia maculata and Thin- leaved Stringybark E. eugenioides representing the dominant Description: Prospect Nature Reserve (Fig. 1) borders Prospect canopy species, and an understorey similar to that of Shale Hills Reservoir and comprises an area of 325.3 hectares. Woodland. The study site (Fig. 1) contains both Shale Hills and Shale Plains Woodlands. -

22 Powers Road SEVEN HILLS

22 Powers Road SEVEN HILLS BUILDING B2 - TOP QUALITY SMALL UNIT - PLENTY OF ACCESS DOORS UNIQUE OPPORTUNITY - MULTIPLE ON-GRADE DOORS LOCATION: RENT: $/sqm pa Net (+GST) 22 Powers Road is a quality Business Park Estate, that offers immediate access to Station Road, $ pa Net (+GST) Prospect Highway, Old Windsor Road and the M2 and M7 Motorways. Seven Hills Railway Station AREA (SQM): Office 155.00 and Bus Interchange is only a short walk from the property. Warehouse 378.00 DESCRIPTION: Total 533.00 Unit B1 will be available in December, get in quick! This space won't be available for long. OUTGOINGS: $/sqm pa (+GST) approx. $ pa (+GST) Unit B1 offers a practical warehouse with a compact office and 12 on-site parking spaces. PARKING: On site parking 22 Powers Road is a premium commercial and industrial estate, conveniently located near the M2 COMMENTS: + AVAILABLE NOW Hills Motorway, M4 Western Motorway and Westlink M7- three major arterial roads that link Seven Hills to other parts of Sydney. Close to public transport, 22 Powers Road is approximately 750 CONTACT: metres from the Seven Hills Railway Station and Bus Terminus. Ben Lindsay Tenants and visitors, enjoy the convenience of the many on-site amenities, including a cafe, with 0421 248 587 outdoor seating, which offers a variety of eat-in and takeaway options. [email protected] T 02 9438 1888 E [email protected] W propertyfox.com.au Sydney CBD Sydney North Sydney West Suite 8.03 Suite 12 Ground Floor Level 8, 14 Martin Place Level 1, 67 Christie Street 79 George Street Sydney NSW 2000 St Leonards NSW 2065 Parramatta NSW 2150 Misrepresentation act - these details and measurements herein do not form any part of any contract and whilst every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, this cannot be guaranteed.. -

Graham Clifton Southwell

Graham Clifton Southwell A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts (Research) Department of Art History Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences University of Sydney 2018 Bronze Southern Doors of the Mitchell Library, Sydney A Hidden Artistic, Literary and Symbolic Treasure Table of Contents Abstract Acknowledgements Chapter One: Introduction and Literature Review Chapter Two: The Invention of Printing in Europe and Printers’ Marks Chapter Three: Mitchell Library Building 1906 until 1987 Chapter Four: Construction of the Bronze Southern Entrance Doors Chapter Five: Conclusion Bibliography i! Abstract Title: Bronze Southern Doors of the Mitchell Library, Sydney. The building of the major part of the Mitchell Library (1939 - 1942) resulted in four pairs of bronze entrance doors, three on the northern facade and one on the southern facade. The three pairs on the northern facade of the library are obvious to everyone entering the library from Shakespeare Place and are well documented. However very little has been written on the pair on the southern facade apart from brief mentions in two books of the State Library buildings, so few people know of their existence. Sadly the excellent bronze doors on the southern facade of the library cannot readily be opened and are largely hidden from view due to the 1987 construction of the Glass House skylight between the newly built main wing of the State Library of New South Wales and the Mitchell Library. These doors consist of six square panels featuring bas-reliefs of different early printers’ marks and two rectangular panels at the bottom with New South Wales wildflowers. -

Reducing the Impact of Weirs on Aquatic Habitat

REDUCING THE IMPACT OF WEIRS ON AQUATIC HABITAT NSW DETAILED WEIR REVIEW REPORT TO THE NEW SOUTH WALES ENVIRONMENTAL TRUST SYDNEY METROPOLITAN CMA REGION Published by NSW Department of Primary Industries. © State of New South Wales 2006. This publication is copyright. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in an unaltered form only (retaining this notice) for your personal use or for non-commercial use within your organisation provided due credit is given to the author and publisher. To copy, adapt, publish, distribute or commercialise any of this publication you will need to seek permission from the Manager Publishing, NSW Department of Primary Industries, Orange, NSW. DISCLAIMER The information contained in this publication is based on knowledge and understanding at the time of writing (July 2006). However, because of advances in knowledge, users are reminded of the need to ensure that information upon which they rely is up to date and to check the currency of the information with the appropriate officer of NSW Department of Primary Industries or the user‘s independent adviser. This report should be cited as: NSW Department of Primary Industries (2006). Reducing the Impact of Weirs on Aquatic Habitat - New South Wales Detailed Weir Review. Sydney Metropolitan CMA region. Report to the New South Wales Environmental Trust. NSW Department of Primary Industries, Flemington, NSW. ISBN: 0 7347 1753 9 (New South Wales Detailed Weir Review) ISBN: 978 0 7347 1833 4 (Sydney Metropolitan CMA region) Cover photos: Cob-o-corn Weir, Cob-o-corn Creek, Northern Rivers CMA (upper left); Stroud Weir, Karuah River, Hunter/Central Rivers CMA (upper right); Mollee Weir, Namoi River, Namoi CMA (lower left); and Hartwood Weir, Billabong Creek, Murray CMA (lower right). -

Government Gazette No 164 of Friday 23 April 2021

GOVERNMENT GAZETTE – 4 September 2020 Government Gazette of the State of New South Wales Number 164–Electricity and Water Friday, 23 April 2021 The New South Wales Government Gazette is the permanent public record of official NSW Government notices. It also contains local council, non-government and other notices. Each notice in the Government Gazette has a unique reference number that appears in parentheses at the end of the notice and can be used as a reference for that notice (for example, (n2019-14)). The Gazette is compiled by the Parliamentary Counsel’s Office and published on the NSW legislation website (www.legislation.nsw.gov.au) under the authority of the NSW Government. The website contains a permanent archive of past Gazettes. To submit a notice for gazettal, see the Gazette page. By Authority ISSN 2201-7534 Government Printer NSW Government Gazette No 164 of 23 April 2021 DATA LOGGING AND TELEMETRY SPECIFICATIONS 2021 under the WATER MANAGEMENT (GENERAL) REGULATION 2018 I, Kaia Hodge, by delegation from the Minister administering the Water Management Act 2000, pursuant to clause 10 of Schedule 8 to the Water Management (General) Regulation 2018 (the Regulation) approve the following data logging and telemetry specifications for metering equipment. Dated this 15 day of April 2021. KAIA HODGE Executive Director, Regional Water Strategies Department of Planning, Industry and Environment By delegation Explanatory note This instrument is made under clause 10 (1) of Schedule 8 to the Regulation. The object of this instrument is to approve data logging and telemetry specifications for metering equipment that holders of water supply work approvals, water access licences and Water Act 1912 licences and entitlements that are subject to the mandatory metering equipment condition must comply with. -

Including the Upper Nepean Scheme), at Which Time It Was Used Only to Flush Creeks and Ponds 14 in the Botanic Gardens.13F13F

by 1890 (including the Upper Nepean Scheme), at which time it was used only to flush creeks and ponds 14 in the Botanic Gardens.13F13F FIGURE 6: WOOLCOTT & CLARKE’S MAP OF THE CITY OF SYDNEY, 1864 (SOURCE: HISTORICAL ATLAS OF SYDNEY) FIGURE 7: BUSBY’S BORE ACROSS HYDE PARK, FINAL FLOW OF WATER ACROSS TRESTLES, TO BE COLLECTED AND DISTRIBUTED BY HORSE DRAWN CART (SOURCE: CITY OF SYDNEY ARCHIVES, CALL NUMBER: SSV1 / WAT) 14 ibid Archaeological Assessment—Sydney Football Stadium Prepared by Curio Projects for Infrastructure NSW 25 FIGURE 8: SECTION OF BUSBY’S BORE NEAR INTERSECTION OF LIVERPOOL AND COLLEGE STREETS, THIS SECTION OF THE BORE WAS CONSTRUCTED AS AN OPEN CUT TRENCH, LAID WITH SANDSTONE MASONRY AND SLAB ROOF (SOURCE: SYDNEY WATER ARCHIVES, REF: A1029) FIGURE 9: BUSBY’S BORE ACCESS POINT AT VICTORIA BARRACKS, PADDINGTON (SOURCE: CITY OF SYDNEY ARCHIVES, FILE. 029\029322) Archaeological Assessment—Sydney Football Stadium Prepared by Curio Projects for Infrastructure NSW 26 FIGURE 10: ORIGINAL 1892 PLAN OF BUSBY’S BORE (N.B. THIS MAP HAS BEEN PROVEN TO HAVE MANY LOCATIONAL INACCURACIES) (SOURCE: SYDNEY WATER ARCHIVES, REF: A1029) 3.4. Rifle Range and Moore Park Following the establishment and completion of construction of the Victoria Park Barracks, it became apparent that additional land was required for both a rifle range, as well as recreational facilities for the troops. Thus in 1849, additional land from the Sydney Common was set aside for a professional military rifle range (Figure 11), followed in 1852 by an additional 25 acres for a ‘military garden and cricket 15 ground’14F14F (the location of which eventually became the Sydney Cricket Ground). -

History of Sydney Water

The history of Sydney Water Since the earliest days of European settlement, providing adequate water and sewerage services for Sydney’s population has been a constant challenge. Sydney Water and its predecessor, the Metropolitan Water Sewerage and Drainage Board, has had a rich and colourful history. This history reflects the development and growth of Sydney itself. Over the past 200 years, Sydney’s unreliable rainfall has led to the development of one of the largest per capita water supplies in the world. A truly reliable water supply was not achieved until the early 1960s after constructing Warragamba Dam. By the end of the 20th Century, despite more efficient water use, Sydney once again faced the prospect of a water shortage due to population growth and unreliable rainfall patterns. In response to this, the NSW Government, including Sydney Water, started an ambitious program to secure Sydney’s water supplies. A mix of options has been being used including water from our dams, desalination, wastewater recycling and water efficiency. Timeline 1700s 1788 – 1826 Sydney was chosen as the location for the first European settlement in Australia, in part due to its outstanding harbour and the availability of fresh water from the Tank Stream. The Tank Stream remained Sydney’s main water source for 40 years. However, pollution rapidly became a problem. A painting by J. Skinner Prout of the Tank Stream in the 1840s 1800s 1880 Legislation was passed under Sir Henry Parkes, as Premier, which constitutes the Board of Water Supply and Sewerage. 1826 The Tank Stream was abandoned as a water supply because of pollution from rubbish, sewage and runoff from local businesses like piggeries. -

Phillips, Michael

Australian Earthquake Engineering Society 2013 Conference, Nov 15-17 2013, Hobart, Tas Measuring Bridge Characteristics to Predict their Response in Earthquakes Michael Phillips1 and Kevin McCue2 1. EPSO Seismic, PO Box 398, Coonabarabran, NSW 2357. Email: [email protected] 2. Adjunct Professor, Central Queensland University, Rockhampton, Qld 4701. Email: [email protected] Abstract During 2011 and 2012 we measured the response of the Sydney Harbour Bridge (SHB) to ambient vibration, and determined the natural frequencies and damping of various low-order resonance modes. These measurements were conducted using a simple triaxial MEMS acceleration sensor located at the mid-point of the road deck. The effectiveness of these measurements suggested that a full mapping of modal amplitudes along the road deck could be achieved by making many incremental measurements along the deck, then using software to integrate these data. To accommodate the briefer spot-measurements required, improved recording equipment was acquired, resulting in much improved data quality. Plotting the SHB deck motion data with 3D graphics nicely presents the modal amplitude characteristics of various low order modes, and this analysis technique was then applied to a more complex bridge structure, namely the road deck of Sydney’s Cahill Expressway Viaduct. Unlike the single span of the SHB, the Cahill Expressway Viaduct (CHE) dramatically changes its modal behavior along its length, and our analysis system highlights a short section of this elevated roadway that is seismically vulnerable. On the basis of these observations, the NSW Roads & Maritime Services (RMS) indicated that they will conduct an investigation into the structure at this location.