The Ascent of Money: a Financial History of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ASA ECONOMIC SOCIOLOGY SECTION NEWSLETTER ACCOUNTS Volume 9 Issue 1 Spring 2010

ASA ECONOMIC SOCIOLOGY SECTION NEWSLETTER ACCOUNTS Volume 9 Issue 1 Spring 2010 Section Chair’s Introduction 2009‐10 Editors Jiwook Jung T Kim Pernell Sameer Srivastava The events of the last year and a half, or two if you were watching things Harvard University closely, have led many to question whether the economy operates as most everyone understood it to operate. The Great Recession has undermined many shibboleths of economic theory and challenged the idea that free markets regulate themselves. The notion that investment bankers and titans of industry would never take risks that might put the economy in jeopardy, because they would pay the price for a collapse, now seems Inside this Issue quaint. They did take such risks, and few of them have paid any kind of price. The CEOs of the leading automakers were chided for using private Markets on Trial: Progress and jets to fly to Washington to testify before Congress, and felt obliged to Prognosis for Economic Sociology’s Response to the Financial Crisis— make their next trips in their own products, but the heads of the investment Report on a Fall 2009 Symposium banks that led us down the road to perdition received healthy bonuses this by Adam Goldstein, UC Berkeley year, as they did last year. The Dollar Standard and the Global ProductionI System: The In this issue of Accounts, the editors chose to highlight challenges to Institutional Origins of the Global conventional economic wisdom. First, we have a first-person account, Financial Crisis by Bai Gao, Duke from UC-Berkeley doctoral candidate Adam Goldstein, of a fall Kellogg Book Summary and Interview: School (Northwestern) symposium titled Markets on Trial: Sociology’s David Stark’s The Sense of Response to the Financial Crisis. -

The Future of Money: from Financial Crisis to Public Resource

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Mellor, Mary Book — Published Version The future of money: From financial crisis to public resource Provided in Cooperation with: Pluto Press Suggested Citation: Mellor, Mary (2010) : The future of money: From financial crisis to public resource, ISBN 978-1-84964-450-1, Pluto Press, London, http://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/30777 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/182430 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further -

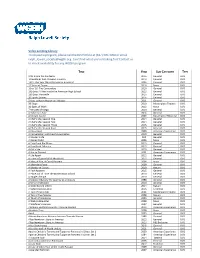

Walpole Public Library DVD List A

Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] Last updated: 9/17/2021 INDEX Note: List does not reflect items lost or removed from collection A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Nonfiction A A A place in the sun AAL Aaltra AAR Aardvark The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.1 vol.1 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.2 vol.2 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.3 vol.3 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.4 vol.4 ABE Aberdeen ABO About a boy ABO About Elly ABO About Schmidt ABO About time ABO Above the rim ABR Abraham Lincoln vampire hunter ABS Absolutely anything ABS Absolutely fabulous : the movie ACC Acceptable risk ACC Accepted ACC Accountant, The ACC SER. Accused : series 1 & 2 1 & 2 ACE Ace in the hole ACE Ace Ventura pet detective ACR Across the universe ACT Act of valor ACT Acts of vengeance ADA Adam's apples ADA Adams chronicles, The ADA Adam ADA Adam’s Rib ADA Adaptation ADA Ad Astra ADJ Adjustment Bureau, The *does not reflect missing materials or those being mended Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] ADM Admission ADO Adopt a highway ADR Adrift ADU Adult world ADV Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ smarter brother, The ADV The adventures of Baron Munchausen ADV Adverse AEO Aeon Flux AFF SEAS.1 Affair, The : season 1 AFF SEAS.2 Affair, The : season 2 AFF SEAS.3 Affair, The : season 3 AFF SEAS.4 Affair, The : season 4 AFF SEAS.5 Affair, -

Video Resources Feature Films Boiler Room

Video Resources Feature Films Boiler Room. New Line Cinema, 2000.A college dropout, attempting to win back his father's high standards he gets a job as a broker for a suburban investment firm, which puts him on the fast track to success, but the job might not be as legitimate as it once appeared to be. Margin Call. Before the Door Pictures, 2011. Follows the key people at an investment bank, over a 24- hour period, during the early stages of the 2008 financial crisis. The Wolf of Wall Street. Universal Pictures, 2013. Based on the true story of Jordan Belfort, from his rise to a wealthy stock-broker living the high life to his fall involving crime, corruption and the federal government. The Big Short. Paramount Pictures,2015. In 2006-7 a group of investors bet against the US mortgage market. In their research they discover how flawed and corrupt the market is. The Last Days of Lehman Brothers. British Broadcasting Corporation, 2009. After six months' turmoil in the world's financial markets, Lehman Brothers was on life support and the government was about to pull the plug. Documentaries Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room. Jigsaw Productions, 2005. A documentary about the Enron Corporation, its faulty and corrupt business practices, and how they led to its fall. Inside Job. Sony Pictures Classics, 2010. Takes a closer look at what brought about the 2008 financial meltdown. Too Big to Fail. HBO Films, 2011. Chronicles the financial meltdown of 2008 and centers on Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson. Money for Nothing: Inside the Federal Reserve. -

UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Playing Along Infinite Rivers: Alternative Readings of a Malay State Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/70c383r7 Author Syed Abu Bakar, Syed Husni Bin Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Playing Along Infinite Rivers: Alternative Readings of a Malay State A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature by Syed Husni Bin Syed Abu Bakar August 2015 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Hendrik Maier, Chairperson Dr. Mariam Lam Dr. Tamara Ho Copyright by Syed Husni Bin Syed Abu Bakar 2015 The Dissertation of Syed Husni Bin Syed Abu Bakar is approved: ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements There have been many kind souls along the way that helped, suggested, and recommended, taught and guided me along the way. I first embarked on my research on Malay literature, history and Southeast Asian studies not knowing what to focus on, given the enormous corpus of available literature on the region. Two years into my graduate studies, my graduate advisor, a dear friend and conversation partner, an expert on hikayats, Hendrik Maier brought Misa Melayu, one of the lesser read hikayat to my attention, suggesting that I read it, and write about it. If it was not for his recommendation, this dissertation would not have been written, and for that, and countless other reasons, I thank him kindly. I would like to thank the rest of my graduate committee, and fellow Southeast Asianists Mariam Lam and Tamara Ho, whose friendship, advice, support and guidance have been indispensable. -

Video Lending Library to Request a Program, Please Call the RLS Hotline at (617) 300-3900 Or Email Ralph Lowell [email protected]

Video Lending Library To request a program, please call the RLS Hotline at (617) 300-3900 or email [email protected]. Can't find what you're looking for? Contact us to check availability for any WGBH program. TITLE YEAR SUB-CATEGORY TYPE 9/11 Inside the Pentagon 2016 General DVD 10 Buildings that Changed America 2013 General DVD 1421: The Year China Discovered America? 2004 General DVD 15 Years of Terror 2016 Nova DVD 16 or ’16: The Contenders 2016 General DVD 180 Days: A Year inside the American High School 2013 General DVD 180 Days: Hartsville 2015 General DVD 20 Sports Stories 2016 General DVD 3 Keys to Heart Health Lori Moscas 2011 General DVD 39 Steps 2010 Masterpiece Theatre DVD 3D Spies of WWII 2012 Nova DVD 7 Minutes of Magic 2010 General DVD A Ballerina’s Tale 2015 General DVD A Certain Justice 2003 Masterpiece Mystery! DVD A Chef’s Life, Season One 2014 General DVD A Chef’s Life, Season Two 2014 General DVD A Chef’s Life, Season Three 2015 General DVD A Chef’s Life, Season Four 2016 General DVD A Class Apart 2009 American Experience DVD A Conversation with Henry Louis Gates 2010 General DVD A Danger's Life N/A General DVD A Daring Flight 2005 Nova DVD A Few Good Pie Places 2015 General DVD A Few Great Bakeries 2015 General DVD A Girl's Life 2010 General DVD A House Divided 2001 American Experience DVD A Life Apart 2012 General DVD A Lover's Quarrel With the World 2012 General DVD A Man, A Plan, A Canal, Panama 2004 Nova DVD A Moveable Feast 2009 General DVD A Murder of Crows 2010 Nature DVD A Path Appears 2015 General -

The Ascent of Money: a Financial History of the World Author: Niall Ferguson Publisher: Penguin Group Date of Publication: November 2008 ISBN: 9781594201929 No

The Ascent of Money: A Financial History of the World Author: Niall Ferguson Publisher: Penguin Group Date of Publication: November 2008 ISBN: 9781594201929 No. of Pages: 432 Buy This Book [Summary published by CapitolReader.com on April 23, 2009] Click here for more political and current events books from Penguin. About The Author: Niall Ferguson is one of Britain’s most renowned historians. He teaches history at both Harvard and Oxford. He is also the author of numerous bestsellers including The War of the World. In addition, Ferguson has brought economics and history to a wider audience through several highly-popular TV documentary series and also through his frequent newspaper and magazine articles. General Overview: Bread, cash, dough, loot: Call it what you like, it matters. To Christians, love of it is the root of all evil. To generals, it’s the sinews of war. To revolutionaries, it’s the chains of labor. But in The Ascent of Money, Niall Ferguson shows that finance is in fact the foundation of human progress. What’s more, he reveals financial history as the essential backstory behind all history. The evolution of credit and debt, in his view, was as important as any technological innovation in the rise of civilization. * Please Note: This CapitolReader.com summary does not offer judgment or opinion on the book’s content. The ideas, viewpoints and arguments are presented just as the book’s author has intended. - Page 1 Reprinted by arrangement with The Penguin Press, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc., from THE ASCENT OF MONEY by Niall Ferguson. -

February 2009

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Inland Empire Business Journal Special Collections & University Archives 2-2009 February 2009 Inland Empire Business Journal Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/iebusinessjournal Part of the Business Commons Recommended Citation Inland Empire Business Journal, "February 2009" (2009). Inland Empire Business Journal. 159. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/iebusinessjournal/159 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections & University Archives at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Inland Empire Business Journal by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ...SiliiTID PAID A E **"""*"AUJO••SCH 1 DIGIT 916 Onwno,('·- \ IHGRlD nHJHOHV Ptmut ,,. I OR CURRfHI OCCUPAHI 6511 CRISTA PAlHA OR HUHIIHGIOH DEACH, CA 9264/ 6617 ourn 11.1 .... 1.1.11 ... 1•• 11,,,1,11 ... 11,,,,,111 ••• 1••• 11 ,,,1111 ... 1 \\\\\\ 0USJOoHI Jl l-01'1 VOLUME 21. UMBER 2 '52.00 February 200L) School for Autism Spectrum Disorders expands to AT DEADLINE meet the needs of the grO\\ing autistic population Special LeRo) Ha)nec., Center It \\a\ jU\t ll\C year\ ago that n----'T::::';J;;:::::.. 11111"'~F., Sections Appoints former Habitat LeRo) llaynes Center tkcided to open ,t clas,room to meet the 'Pl' Thr ( rtdit l'nsrs an Inland t.mptre for Humanit) controller as Opportumh? Quarttrl) Eronollllf cial need' of thL' grovv ing autistJL' nen chief financial officer Report population. The former controller for Focus is placed on the develop Pg. 3 Pg.J! I laoitat for llumantt) of Greater mg. -

THE ASCENT of MONEY: a FINANCIAL HISTORY of the WORLD Niall Ferguson, 2008, Penguin Books Ltd., London, UK, Pp

THE ASCENT OF MONEY: A FINANCIAL HISTORY OF THE WORLD Niall Ferguson, 2008, Penguin Books Ltd., London, UK, pp. 350 Review* Niall Ferguson is considered one of the most influential of economic historians. In his latest book The ascent of money: a financial history of the world he boldly argues that fi- nance is behind every major event in history. But if financial history is one of the key ele- ments in interpreting history, then surely it deserves more attention than 350 pages. The proper subtitle of his book might as well be A very concise financial history of the world. The reason why this book is relatively short, especially when the title is so ambitious, is that it was written as a script for a TV show of the same name, and I guess Ferguson fa- iled to obtain funding for more than four episodes. The fact that this book is also a TV show is important in understanding its structure of arguments. The book is full of histori- cal examples, biographies of people who have shaped finance in their times, which makes this book very enjoyable to read (and watch), but which does not necessary contribute to rigorous analysis or strengthen its arguments. In fact, the target group of this book seems to be “ordinary” people and not economic historians or finance experts. Even if this book is not an epitome of rigorous scientific analysis, its conclusions cle- arly make it a part of the liberal camp of economic thought. Possibly one of the boldest claims of this book is that in spite of the recent crisis, the direction of development of fi- nance is clearly upwards. -

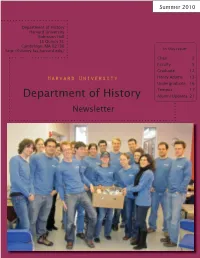

2010 Alumni Newsletter Draft.Indd

Summer 2010 Department of History Harvard University Robinson Hall 35 Quincy St. Cambridge, MA 02138 In this issue: http://history.fas.harvard.edu/ Chair 2 Faculty 5 Graduate 12 Harvard University Henry Adams 13 Undergraduate 16 Tempus 17 Department of History Alumni Updates 21 Newsletter From the Chair reetings and distributing them, have had the completion of Laurel Ulrich’s Gfrom their own benefits, in this case presidency of the American His- CCambridge, contributing to a more sustain- torical Association in January with Massachu- able future. The History Depart- a party at the AHA co-sponsored setts, at the ment has also partnered with the with the History Department of eend of the History of Science Department the University of New Hampshire, 2009-10 aca- to pioneer a new administrative where Laurel previously taught, ddemic year. structure designed to save costs and Alfred A. Knopf, her pub- I am com- by combining staff and services lisher. (See photo on page 3.) We ing to the across departments. Aided by this gave our deep thanks to staff as- cconclusion new administrative support group, sistant Laura Johnson, well loved of my two- our History Department staff have by current and former students year stint as Chair of the History worked harder than ever to handle and faculty as the mainstay of the Department. My colleague in US the department’s work load and Undergraduate Program (former History, Jim Kloppenberg, will re- for that we are extremely grateful. Tutorial) Office, who was honored turn to the helm for the next two In the spirit of being as construc- for 25 years of service to Harvard, years, after which I will serve a tive as possible in the face of the all of it spent in Robinson 101 final year. -

The Ethical Stance in Banking

The Ethical Stance in Banking Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Philosophie an der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universiät München vorgelegt von Jesús Simeón Villa aus den Philippinen 2010 Referent: Prof. Dr. Wilhelm Vossenkuhl Korreferent: PD Dr. Stephan Sellmaier Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 19.07.2010 Acknowledgements This thesis is especially dedicated to my wife, Joy, whose loving encouragement has enabled me to envisage and achieve my doctoral contribution to the field of ethics. I wish to express my gratitude to all those who made it possible for me to complete my thesis. Above all, I am deeply indebted to Prof. Dr. Wilhelm Vossenkuhl for providing me excellent advice and support as my supervisor and subsequent examiner, to Prof. Jeff Malpas of the University of Tasmania for his attentive supervision and positive suggestions. I am similarly grateful to PD Dr. Stephan Sellmaier for allowing me to work in the Münchner Kompetenzzentrum Ethik and for agreeing to be my second examiner, and to Prof. Dr. Tobias Döring for his encouragement and agreement to act as my third examiner. Special thanks go to all the individuals, financial institutions, and regulators in Hong Kong and Australia for their participation in my empirical research, and to Vernon Moore and John McCleod for their assistance therewith. There are many others to whom I owe my gratitude for their contribution: Dr. Valerie Hazel for valuable assistance on formatting; my daughter, Giselle Villa- Hansen for reviewing and merging my documents: Dr. Brita Hansen for proofreading; Kristine Hinterholzinger for her help on the Zusammenfassung. Contents ABSTRACT ...................................................................................................................................................1 PART A. -

The Ascent of Money: a Financial History of the World

NIALL FERGUSON Author of THE WAR OF THE WORLD THE ASCENT OF MONEY A FINANCIAL HISTORY of THE WORLD U.S. $29.95 Canada $33.00 Bread, cash, dosh, dough, loot: Call it what you like, it matters. To Christians, love of it is the root of all evil. To generals, it's the sinews of war. To revolu tionaries, it's the chains of labor. But in The Ascent of Money, Niall Ferguson shows that finance is in fact the foundation of human progress. What's more, he reveals financial history as the essential backstory behind all history. The evolution of credit and debt was as impor tant as any technological innovation in the rise of civilization, from ancient Babylon to the silver mines of Bolivia. Banks provided the material basis for the splendors of the Italian Renaissance while the bond market was the decisive factor in conflicts from the Seven Years' War to the American Civil War. With the clarity and verve for which he is known, Ferguson explains why the origins of the French Revolution lie in a stock market bubble caused by a convicted Scots murderer. He shows how financial failure turned Argentina from the world's sixth richest country into an inflation- ridden basket case—and how a financial revolution is propelling the world's most populous country from poverty to power in a single generation. Yet the most important lesson of the financial history is that sooner or later every bubble bursts —sooner or later the bearish sellers outnumber the bullish buyers, sooner or later greed flips into fear.