Contextualizing the Current Crisis: Post-Fordism, Neoliberal Restructuring, and Financialization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ASA ECONOMIC SOCIOLOGY SECTION NEWSLETTER ACCOUNTS Volume 9 Issue 1 Spring 2010

ASA ECONOMIC SOCIOLOGY SECTION NEWSLETTER ACCOUNTS Volume 9 Issue 1 Spring 2010 Section Chair’s Introduction 2009‐10 Editors Jiwook Jung T Kim Pernell Sameer Srivastava The events of the last year and a half, or two if you were watching things Harvard University closely, have led many to question whether the economy operates as most everyone understood it to operate. The Great Recession has undermined many shibboleths of economic theory and challenged the idea that free markets regulate themselves. The notion that investment bankers and titans of industry would never take risks that might put the economy in jeopardy, because they would pay the price for a collapse, now seems Inside this Issue quaint. They did take such risks, and few of them have paid any kind of price. The CEOs of the leading automakers were chided for using private Markets on Trial: Progress and jets to fly to Washington to testify before Congress, and felt obliged to Prognosis for Economic Sociology’s Response to the Financial Crisis— make their next trips in their own products, but the heads of the investment Report on a Fall 2009 Symposium banks that led us down the road to perdition received healthy bonuses this by Adam Goldstein, UC Berkeley year, as they did last year. The Dollar Standard and the Global ProductionI System: The In this issue of Accounts, the editors chose to highlight challenges to Institutional Origins of the Global conventional economic wisdom. First, we have a first-person account, Financial Crisis by Bai Gao, Duke from UC-Berkeley doctoral candidate Adam Goldstein, of a fall Kellogg Book Summary and Interview: School (Northwestern) symposium titled Markets on Trial: Sociology’s David Stark’s The Sense of Response to the Financial Crisis. -

The Future of Money: from Financial Crisis to Public Resource

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Mellor, Mary Book — Published Version The future of money: From financial crisis to public resource Provided in Cooperation with: Pluto Press Suggested Citation: Mellor, Mary (2010) : The future of money: From financial crisis to public resource, ISBN 978-1-84964-450-1, Pluto Press, London, http://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/30777 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/182430 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further -

Walpole Public Library DVD List A

Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] Last updated: 9/17/2021 INDEX Note: List does not reflect items lost or removed from collection A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Nonfiction A A A place in the sun AAL Aaltra AAR Aardvark The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.1 vol.1 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.2 vol.2 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.3 vol.3 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.4 vol.4 ABE Aberdeen ABO About a boy ABO About Elly ABO About Schmidt ABO About time ABO Above the rim ABR Abraham Lincoln vampire hunter ABS Absolutely anything ABS Absolutely fabulous : the movie ACC Acceptable risk ACC Accepted ACC Accountant, The ACC SER. Accused : series 1 & 2 1 & 2 ACE Ace in the hole ACE Ace Ventura pet detective ACR Across the universe ACT Act of valor ACT Acts of vengeance ADA Adam's apples ADA Adams chronicles, The ADA Adam ADA Adam’s Rib ADA Adaptation ADA Ad Astra ADJ Adjustment Bureau, The *does not reflect missing materials or those being mended Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] ADM Admission ADO Adopt a highway ADR Adrift ADU Adult world ADV Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ smarter brother, The ADV The adventures of Baron Munchausen ADV Adverse AEO Aeon Flux AFF SEAS.1 Affair, The : season 1 AFF SEAS.2 Affair, The : season 2 AFF SEAS.3 Affair, The : season 3 AFF SEAS.4 Affair, The : season 4 AFF SEAS.5 Affair, -

A Critique of the Fordism of the Regulation School

A Critique of the Fordism of the Regulation School Ferruccio Gambino1 Introduction Some of the categories that people have used in recent years to describe the changes taking place in the world of production, such as Fordism, post-Fordism and immaterial production, have shown themselves to be rather blunt instruments.2 Here I intend to deal with the use of the concepts “Fordism” and “post-Fordism” by the regulation school, which has given a particular twist to the former term, and which coined ex novo the latter. The aim of my article is to help break the conflict-excluding spell under which the regulation school has succeeded in casting Fordism and post-Fordism. From midway through the 1970s, as a result of the writings of Michel Aglietta3 and then of other exponents of the regulation school, 1 The English version of this paper appeared in 1996 in Common Sense no. 19 and was subsequently published as a chapter in Werner Bonefeld (ed), Revolutionary Writing: Common Sense Essays In Post-Political Politics Writing, New York, Autonomedia, 2003. 2 For a timely critique of the term “immaterial production”, see Sergio Bologna, “Problematiche del lavoro autonomo in Italia” (Part I), Altreragioni, no. 1 (1992), pp. 10-27. 3 Michel Aglietta, (1974), Accumulation et régulation du capitalisme en longue période. L’exemple des Etats Unis (1870-1970), Paris, INSEE, 1974; the second French edition has the title Régulation et crises du capitalisme, Paris, Calmann- Lévy, 1976; English translation, A Theory of Capitalist Regulation: the US Experience, London and New York, Verso, 1979; in 1987 there followed a second English edition from the same publisher. -

The Domestication of Ford Model T in Denmark

Aalborg Universitet The Domestication of Ford Model T in Denmark Wagner, Michael Publication date: 2009 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication from Aalborg University Citation for published version (APA): Wagner, M. (2009). The Domestication of Ford Model T in Denmark. Paper presented at Appropriating America Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. ? Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. ? You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain ? You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us at [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from vbn.aau.dk on: September 24, 2021 The domestication of Ford Model T in Denmark By Michael F. Wagner, Institute for History and Social Studies, Aalborg University Ford Motor Company started to operate on a commercial level in Denmark from 1907 by appointing a sales agent, Bülow & Co., as importer of Ford automobiles to the Scandinavian market. The major breakthrough for the company on a global scale came with the introduction of the Model T by the end of 1908. -

Video Resources Feature Films Boiler Room

Video Resources Feature Films Boiler Room. New Line Cinema, 2000.A college dropout, attempting to win back his father's high standards he gets a job as a broker for a suburban investment firm, which puts him on the fast track to success, but the job might not be as legitimate as it once appeared to be. Margin Call. Before the Door Pictures, 2011. Follows the key people at an investment bank, over a 24- hour period, during the early stages of the 2008 financial crisis. The Wolf of Wall Street. Universal Pictures, 2013. Based on the true story of Jordan Belfort, from his rise to a wealthy stock-broker living the high life to his fall involving crime, corruption and the federal government. The Big Short. Paramount Pictures,2015. In 2006-7 a group of investors bet against the US mortgage market. In their research they discover how flawed and corrupt the market is. The Last Days of Lehman Brothers. British Broadcasting Corporation, 2009. After six months' turmoil in the world's financial markets, Lehman Brothers was on life support and the government was about to pull the plug. Documentaries Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room. Jigsaw Productions, 2005. A documentary about the Enron Corporation, its faulty and corrupt business practices, and how they led to its fall. Inside Job. Sony Pictures Classics, 2010. Takes a closer look at what brought about the 2008 financial meltdown. Too Big to Fail. HBO Films, 2011. Chronicles the financial meltdown of 2008 and centers on Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson. Money for Nothing: Inside the Federal Reserve. -

The Paradox of Positivism

Dylan Riley The Paradox of Positivism The essays in The Politics of Method in the Human Sciences contribute to a historical and comparative sociology of social science by systematically com- paring the rises, falls, and absences of ‘‘methodological positivism’’ across the human sciences. Although all of the essays are of extremely high quality, three contributions develop the argument most fully: George Steinmetz’s introduction and William H. Sewell Jr.’s and Steinmetz’s contributions to the volume. My remarks focus on these three pieces, drawing on the other contributions to illustrate aspects of the argument or to suggest tensions that need exploration. What Is Positivism? What are the authors trying to explain? The term positivism has at least three meanings. It can be a commitment to social evolution in the sense of Auguste Comte and Emile Durkheim. It can refer to an articulated philosophical tra- dition: logical positivism. Or it can refer to a set of scientific research prac- tices: methodological positivism. It is the last meaning that is most relevant for Steinmetz (2005c: 109). Methodological positivism refers to a concept of knowledge, a concept of social reality, and a concept of science. First, it is an epistemology that identifies scientific knowledge with covering laws—that is, statements of the type ‘‘if A occurs, then B will follow.’’ Second, it is an ontology that equates existence with objects that are observable. Third, it is associated with a self- understanding of scientific activity in which social science is independent -

“Comparative Urbanism” in Post- Fordist Cities

Journal for interdisciplinary research in architecture, design and planning contourjournal.org RESEARCH ARTICLE COMPARING HABITATS The Challenges of “Comparative Urbanism” in Post- Fordist Cities: The cases of Turin and Detroit AUTHORS Asma Mehan 1 AFFILIATIONS 1 CITTA - Research Center for Territory, Transports and Environment. University of Porto UP . Portugal CONTACT [email protected] 1 | September 15, 2019 | DOI https://doi.org/10.6666/contour.v0i4.92 ASMA MEHAN Abstract In 1947, the U.S. Secretary of State, George C. Marshall announced that the USA would provide development aid to help the recovery and reconstruction of the economies of Europe, which was widely known as the ‘Marshall Plan’. In Italy, this plan generated a resurgence of modern industrialization and remodeled Italian Industry based on American models of production. As the result of these transnational transfers, the systemic approach known as Fordism largely succeeded and allowed some Italian firms such as Fiat to flourish. During this period, Detroit and Turin, homes to the most powerful automobile corporations of the twentieth century, became intertwined in a web of common features such as industrial concentration, mass flows of immigrations, uneven urban sprawl, radical iconography and inner-city decay, which characterized Fordism in both cities. In the crucial decades of the postwar expansion of the automobile industries, both cities were hubs of labor battles and social movements. However, after the radical decline in their industries as previous auto cities, they experienced the radical shift toward post-Fordist urbanization and production of political urbanism. This research responds to the recent interest for a comparative (re)turn in urban studies by suggesting the conceptual theoretical baseline for the proposed comparative framework in post-Fordist cities. -

UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Playing Along Infinite Rivers: Alternative Readings of a Malay State Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/70c383r7 Author Syed Abu Bakar, Syed Husni Bin Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Playing Along Infinite Rivers: Alternative Readings of a Malay State A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature by Syed Husni Bin Syed Abu Bakar August 2015 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Hendrik Maier, Chairperson Dr. Mariam Lam Dr. Tamara Ho Copyright by Syed Husni Bin Syed Abu Bakar 2015 The Dissertation of Syed Husni Bin Syed Abu Bakar is approved: ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements There have been many kind souls along the way that helped, suggested, and recommended, taught and guided me along the way. I first embarked on my research on Malay literature, history and Southeast Asian studies not knowing what to focus on, given the enormous corpus of available literature on the region. Two years into my graduate studies, my graduate advisor, a dear friend and conversation partner, an expert on hikayats, Hendrik Maier brought Misa Melayu, one of the lesser read hikayat to my attention, suggesting that I read it, and write about it. If it was not for his recommendation, this dissertation would not have been written, and for that, and countless other reasons, I thank him kindly. I would like to thank the rest of my graduate committee, and fellow Southeast Asianists Mariam Lam and Tamara Ho, whose friendship, advice, support and guidance have been indispensable. -

S Name Is Fordism Simon Clarke, Department of Sociology, University of Warwick

What in the F---’s name is Fordism Simon Clarke, Department of Sociology, University of Warwick British Sociological Association Conference, University of Surrey Wednesday, 4th April 1990 There is a widespread belief that the 1980s marked a period of transition to a new epoch of capitalism, underlying which were fundamental changes in the forms of capitalist production. There is little agreement over the precise contours of the new epoch, or even over the term by which it is to be called, but there is a near universal consensus that it derives from the crisis and breakdown of something called „Fordism‟. The one thing that unites the exponents of „neo-Fordism‟, „post-Fordism‟, „post-Modernism‟, „Toyotism‟, „Nextism‟, „Benettonism‟, „Proudhonism‟, „Japanisation‟, „flexible specialisation‟, etc. is that the new „mode of accumulation‟, or „mode of life‟, is „Not-Fordism‟. Behind all the disagreements is a consensus that the 1960s marked the apogee of something called „Fordism‟, the 1970s was marked by the „crisis of Fordism‟, the 1980s marked the transition to „Not-Fordism‟, which will be realised in the 1990s. Much energy has been expended in debating the diffuse characterisations of „Not-Fordism‟. However, much less attention has been paid to the characterisation of Fordism. In this paper I want to ask the simple question „What in the Ford‟s name is Fordism?‟ In view of the title of the session as a whole I will keep a particular eye on the supposed „inflexibility‟ of Fordism.1 The Life and Works of Our Ford The Fordist technological revolution Where better to begin our quest than with the technical revolution which Henry Ford carried through at the Ford Motor Company. -

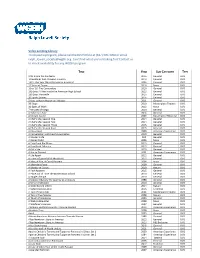

Video Lending Library to Request a Program, Please Call the RLS Hotline at (617) 300-3900 Or Email Ralph Lowell [email protected]

Video Lending Library To request a program, please call the RLS Hotline at (617) 300-3900 or email [email protected]. Can't find what you're looking for? Contact us to check availability for any WGBH program. TITLE YEAR SUB-CATEGORY TYPE 9/11 Inside the Pentagon 2016 General DVD 10 Buildings that Changed America 2013 General DVD 1421: The Year China Discovered America? 2004 General DVD 15 Years of Terror 2016 Nova DVD 16 or ’16: The Contenders 2016 General DVD 180 Days: A Year inside the American High School 2013 General DVD 180 Days: Hartsville 2015 General DVD 20 Sports Stories 2016 General DVD 3 Keys to Heart Health Lori Moscas 2011 General DVD 39 Steps 2010 Masterpiece Theatre DVD 3D Spies of WWII 2012 Nova DVD 7 Minutes of Magic 2010 General DVD A Ballerina’s Tale 2015 General DVD A Certain Justice 2003 Masterpiece Mystery! DVD A Chef’s Life, Season One 2014 General DVD A Chef’s Life, Season Two 2014 General DVD A Chef’s Life, Season Three 2015 General DVD A Chef’s Life, Season Four 2016 General DVD A Class Apart 2009 American Experience DVD A Conversation with Henry Louis Gates 2010 General DVD A Danger's Life N/A General DVD A Daring Flight 2005 Nova DVD A Few Good Pie Places 2015 General DVD A Few Great Bakeries 2015 General DVD A Girl's Life 2010 General DVD A House Divided 2001 American Experience DVD A Life Apart 2012 General DVD A Lover's Quarrel With the World 2012 General DVD A Man, A Plan, A Canal, Panama 2004 Nova DVD A Moveable Feast 2009 General DVD A Murder of Crows 2010 Nature DVD A Path Appears 2015 General -

The Ascent of Money: a Financial History of the World Author: Niall Ferguson Publisher: Penguin Group Date of Publication: November 2008 ISBN: 9781594201929 No

The Ascent of Money: A Financial History of the World Author: Niall Ferguson Publisher: Penguin Group Date of Publication: November 2008 ISBN: 9781594201929 No. of Pages: 432 Buy This Book [Summary published by CapitolReader.com on April 23, 2009] Click here for more political and current events books from Penguin. About The Author: Niall Ferguson is one of Britain’s most renowned historians. He teaches history at both Harvard and Oxford. He is also the author of numerous bestsellers including The War of the World. In addition, Ferguson has brought economics and history to a wider audience through several highly-popular TV documentary series and also through his frequent newspaper and magazine articles. General Overview: Bread, cash, dough, loot: Call it what you like, it matters. To Christians, love of it is the root of all evil. To generals, it’s the sinews of war. To revolutionaries, it’s the chains of labor. But in The Ascent of Money, Niall Ferguson shows that finance is in fact the foundation of human progress. What’s more, he reveals financial history as the essential backstory behind all history. The evolution of credit and debt, in his view, was as important as any technological innovation in the rise of civilization. * Please Note: This CapitolReader.com summary does not offer judgment or opinion on the book’s content. The ideas, viewpoints and arguments are presented just as the book’s author has intended. - Page 1 Reprinted by arrangement with The Penguin Press, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc., from THE ASCENT OF MONEY by Niall Ferguson.