REG: Sustainable Tourism Development Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of the Anlong Veng Community a History Of

A HIstoRy Of Anlong Veng CommunIty A wedding in Anlong Veng in the early 1990s. (Cover photo) Aer Vietnamese forces entered Cambodia in 1979, many Khmer Rouge forces scaered to the jungles, mountains, and border areas. Mountain 1003 was a prominent Khmer Rouge military base located within the Dangrek Mountains along the Cambodian-Thai border, not far from Anlong Veng. From this military base, the Khmer Rouge re-organized and prepared for the long struggle against Vietnamese and the People’s Republic of Kampuchea government forces. Eventually, it was from this base, Khmer Rouge forces would re-conquer and sele Anlong Veng in early 1990 (and a number of other locations) until their re-integration into Cambodian society in late 1998. In many ways, life in Anlong Veng was as difficult and dangerous as it was in Mountain 1003. As one of the KR strongholds, Anlong Veng served as one of the key launching points for Khmer Rouge guerrilla operations in Cambodia, and it was subject to constant aacks by Cambodian government forces. Despite the perilous circumstances and harsh environment, the people who lived in Anlong Veng endeavored, whenever possible, to re-connect with and maintain their rich cultural heritage. Tossed from the seat of power in 1979, the Khmer Rouge were unable to sustain their rigid ideo- logical policies, particularly as it related to community and family life. During the Democratic Movement of the Khmer Rouge Final Stronghold Kampuchea regime, 1975–79, the Khmer Rouge prohibited the traditional Cambodian wedding ceremony. Weddings were arranged by Khmer Rouge leaders and cadre, who oen required mass ceremonies, with lile regard for tradition or individual distinction. -

History a Work in Progress in One-Time KR Stronghold May Titthara January 25, 2011

History a work in progress in one-time KR stronghold May Titthara January 25, 2011 Sitting under a tree outside Malai High School, 20-year-old Phen Soeurm offers a dismissive approach to his history class typical of many his age. As the teacher lectures, “the class just listens without paying attention at all,” Phen Soeurm says. “They just want to kill time.” Here in this dusty district of Banteay Meanchey province, however, there is more to this phenomenon than a simple case of student laziness. The lecture in question covers the history of the Democratic Kampuchea regime, an understandably sensitive topic in this former Khmer Rouge stronghold. “Most students don’t want to study Khmer Rouge history because they don’t want to be reminded of what happened, and because all of their parents are former Khmer Rouge,” Phen Soeurm said. In schools throughout the Kingdom, the introduction of KR-related material has been a sensitive project. Prior to last year, high school history tests drew from a textbook that gave short shrift to the regime and its history, omitting some of the most basic facts about it. But on the 2010 national history exam, five of the 14 questions dealt with the Khmer Rouge period. In addition to identifying regime leaders, students are asked to explain why it is said that Tuol Sleng prison was a tragedy for the Cambodian people; who was behind Tuol Sleng; how the administrative zones of Democratic Kampuchea were organised; and when the regime was in power. These new additions to the exam follow the 2007 introduction of a government-approved textbook created by the Documentation Centre of Cambodia titled A History of Democratic Kampuchea. -

Data Collection Survey on Electric Power Sector in Cambodia Final Report

Kingdom of Cambodia Data Collection Survey on Electric Power Sector in Cambodia Final Report March 2012 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) The Chugoku Electric Power Co., Inc. SAP JR 12 -021 Data Collection Survey on Electric Power Sector in Cambodia Final Report Contents Chapter 1 Background, Objectives and Scope of Study……...............................................................1-1 1.1 Background of the Study………....................................................................................................1-1 1.2 Objectives of the Study...................................................................................................................1-1 1.3 Supported agencies of the study.....................................................................................................1-2 1.4 Road map of study..........................................................................................................................1-2 Chapter 2 Current Status of the Power Sector in Cambodia................................................................2-1 2.1 Organizations of the Power Sector.................................................................................................2-1 2.1.1 Structure of the power sector.............................................................................................2-1 2.1.2 MIME................................................................................................................................2-1 2.1.3 EAC...................................................................................................................................2-3 -

Report on Power Sector of the Kingdom of Cambodia

ELECTRICITY AUTHORITY OF CAMBODIA REPORT ON POWER SECTOR OF THE KINGDOM OF CAMBODIA 2013 EDITION Compiled by Electricity Authority of Cambodia from Data for the Year 2012 received from Licensees Electricity Authority of Cambodia ELECTRICITY AUTHORITY OF CAMBODIA REPORT ON POWER SECTOR OF THE KINGDOM OF CAMBODIA 2013 EDITION Compiled by Electricity Authority of Cambodia from Data for the Year 2012 received from Licensees Report on Power Sector for the Year 2012 0 Electricity Authority of Cambodia Preface The Annual Report on Power Sector of the Kingdom of Cambodia 2013 Edition is compiled from informations for the year 2012 availble with EAC and received from licensees, MIME and other organizations in the power sector. The data received from some licensees may not up to the required level of accuracy and hence the information provided in this report may be taken as indicative. This report is for dissemination to the Royal Government, institutions, investors and public desirous to know about the situation of the power sector of the Kingdom of Cambodia during the year 2012. With addition of more HV transmission system and MV sub-transmission system, more and more licensees are getting connected to the grid supply. This has resulted in improvement in the quality of supply to more consumers. By end of 2012, more than 91% of the consumers are connected to the grid system. More licensees are now supplying electricity for 24 hours a day. The grid supply has reduced the cost of supply and consequently the tariff for supply to consumers. Due to lower cost and other measures taken by Royal Government of Cambodia, in 2012 there has been a substantial increase in the number of consumers availing electricity supply. -

Budgetworldclass Drives

Budget WorldClass Drives Chiang Mai-Sukhothai Loop a m a z i n g 1998 Tourism Authority of Thailand (TAT) SELF DRIVE VACATIONS THAILAND 1999 NORTHERN THAILAND : CHIANG MAI - SUKHOTHAI AND BURMESE BORDERLANDS To Mae Hong Son To Fang To Chiang Rai To Wang Nua To Chiang Rai 1001 1096 1 107 KHUN YUAM 118 1317 1 SAN KAMPHAENG 1269 19 CHIANG MAI1006 MAE ON 1317 CHAE HOM HANG DONG SARAPHI 108 Doi Inthanon 106 SAN PA TONG 11 LAMPHUN 1009 108 116 MAE CHAEM 103 1156 PA SANG 1035 1031 1033 18 MAE THA Thung Kwian MAE LA NOI 11 Market 1088 CHOM TONG 1010 1 108 Thai Elephant HANG CHAT BAN HONG 1093 Conservation 4 2 1034 Centre 3 LAMPANG 11 To 106 1184 Nan 15 16 HOD Wat Phrathat 1037 LONG 17 MAE SARIANG 108 Lampang Luang KO KHA 14 MAE 11 PHRAE km.219 THA Ban Ton Phung 1103 THUNG 1 5 SUNGMEN HUA SOEM 1099 DOI TAO NGAM 1023 Ban 1194 SOP MOEI CHANG Wiang Kosai DEN CHAI Mae Sam Laep 105 1274 National Park WANG CHIN km.190 Mae Ngao 1125 National Park 1124 LI SOP PRAP OMKOI 1177 101 THOEN LAP LAE UTTARADIT Ban Tha 102 Song Yang Ban Mae Ramoeng MAE SI SATCHANALAI PHRIK 1294 Mae Ngao National Park 1305 6 Mae Salit Historical 101 km.114 11 1048 THUNG Park SAWAN 105 SALIAM 1113 7 KHALOK To THA SONG SAM NGAO 1113 Phitsa- YANG Bhumipol Dam Airport nuloke M Y A N M A R 1056 SI SAMRONG 1113 1195 Sukhothai 101 ( B U R M A ) 1175 9 Ban Tak Historical 1175 Ban 12 Phrathat Ton Kaew 1 Park BAN Kao SUKHOTHAI MAE RAMAT 12 DAN LAN 8 10 105 Taksin 12 HOI Ban Mae Ban National Park Ban Huai KHIRIMAT Lamao 105 TAK 1140 Lahu Kalok 11 105 Phrathat Hin Kiu 13 104 1132 101 12 Hilltribe Lan Sang Miyawadi MAE SOT Development National Park Moei PHRAN KRATAI Bridge 1090 Centre 1 0 10 20 kms. -

Searching for the TRUTH

Magazine of the Documentation Center of Cambodia Searching for THE TRUTH w Reconciliation from the Destruction of the Genocide w Phnom Kraol Security Center and Cardres Purged at Region 105 “Recalling May 20th makes me think about the Khmer Rouge regime SpecialEnglish Edition and especially the death of my father. The Khmer Rouge forced my Second Quater 2016 father to dig the grave to bury himself” -- Rous Vannat, Khmer Rouge Survivor Searching for the truth. TABLE OF CONTENTS Magazine of the Documentation Center of Cambodia Special English Edition, Second Quarter 2016 EDITORIAL u Reconciliation from the Destruction of the Genocide.....................................1 DOCUMENTATION u Ty Sareth and the Traitorous Plans Against Angkar..........................................3 u Men Phoeun Chief of Statistics of the North-West Region.............................7 u News for Revolutionary Male and Female Youth...........................................13 HISTORY u I Believe in Good Deeds.............................................................................................16 u My Uncle Died because of Visting Hometown.................................................20 u The Murder in Region 41 under the Control of Ta An.................................22 u May 20: The Memorial of My Father’s Death....................................................25 u Ouk Nhor, Former Sub-Chief of Prey Pdao Cooperative..............................31 u Nuon Chhorn, Militiawoman...................................................................................32 -

Land Transactions in Rural Cambodia a Synthesis of Findings from Research on Appropriation and Derived Rights to Land

Études et Travaux en ligne no 18 Pel Sokha, Pierre-Yves Le Meur, Sam Vitou, Laing Lan, Pel Setha, Hay Leakhena & Im Sothy Land Transactions in Rural Cambodia A Synthesis of Findings from Research on Appropriation and Derived Rights to Land LES ÉDITIONS DU GRET Land Transactions in Rural Cambodia Document Reference Pel Sokha, Pierre-Yves Le Meur, Sam Vitou, Laing Lan, Pel Setha, Hay Leakhen & Im Sothy, 2008, Land Transactions in Rural Cambodia : A synthesis of Findings from Research on Appropriation and Derived Rights to Land, Coll. Études et Travaux, série en ligne n°18, Éditions du Gret, www.gret.org, May 2008, 249 p. Authors: Pel Sokha, Pierre-Yves Le Meur, Sam Vitou, Laing Lan, Pel Setha, Hay Leakhen & Im Sothy Subject Area(s): Land Transactions Geographic Zone(s): Cambodia Keywords: Rights to Land, Rural Development, Land Transaction, Land Policy Online Publication: May 2008 Cover Layout: Hélène Gay Études et Travaux Online collection This collection brings together papers that present the work of GRET staff (research programme results, project analysis documents, thematic studies, discussion papers, etc.). These documents are placed online and can be downloaded for free from GRET’s website (“online resources” section): www.gret.org They are also sold in printed format by GRET’s bookstore (“publications” section). Contact: Éditions du Gret, [email protected] Gret - Collection Études et Travaux - Série en ligne n° 18 1 Land Transactions in Rural Cambodia Contents Acknowledgements.................................................................................................................................. -

Cambodian Journal of Natural History

Cambodian Journal of Natural History Giant ibis census Patterns of salt lick use Protected area revisions Economic contribution of NTFPs New plants, bees and range extensions June 2016 Vol. 2016 No. 1 Cambodian Journal of Natural History ISSN 2226–969X Editors Email: [email protected] • Dr Neil M. Furey, Chief Editor, Fauna & Flora International, Cambodia. • Dr Jenny C. Daltry, Senior Conservation Biologist, Fauna & Flora International, UK. • Dr Nicholas J. Souter, Mekong Case Study Manager, Conservation International, Cambodia. • Dr Ith Saveng, Project Manager, University Capacity Building Project, Fauna & Flora International, Cambodia. International Editorial Board • Dr Stephen J. Browne, Fauna & Flora International, • Dr Sovanmoly Hul, Muséum National d’Histoire Singapore. Naturelle, Paris, France. • Dr Martin Fisher, Editor of Oryx – The International • Dr Andy L. Maxwell, World Wide Fund for Nature, Journal of Conservation, Cambridge, U.K. Cambodia. • Dr L. Lee Grismer, La Sierra University, California, • Dr Brad Pett itt , Murdoch University, Australia. USA. • Dr Campbell O. Webb, Harvard University Herbaria, • Dr Knud E. Heller, Nykøbing Falster Zoo, Denmark. USA. Other peer reviewers for this volume • Prof. Leonid Averyanov, Komarov Botanical Institute, • Neang Thy, Minstry of Environment, Cambodia. Russia. • Dr Nguyen Quang Truong, Institute of Ecology and • Prof. John Blake, University of Florida, USA. Biological Resources, Vietnam. • Dr Stephan Gale, Kadoorie Farm & Botanic Garden, • Dr Alain Pauly, Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Hong Kong. Sciences, Belgium. • Fredéric Goes, Cambodia Bird News, France. • Dr Colin Pendry, Royal Botanical Garden, Edinburgh, • Dr Hubert Kurzweil, Singapore Botanical Gardens, UK. Singapore. • Dr Stephan Risch, Leverkusen, Germany. • Simon Mahood, Wildlife Conservation Society, • Dr Nophea Sasaki, University of Hyogo, Japan. -

A Comparative Study of Transitional Justice Between the Rwandan

Theiring: The Policy of Truth: A Comparative Study of Transitional Justice Theiringcamera ready (Do Not Delete) 6/20/2018 11:11 AM COMMENT THE POLICY OF TRUTH: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF TRANSITIONAL JUSTICE BETWEEN THE RWANDAN GACACA COURT AND THE EXTRAORDINARY CHAMBERS IN THE COURTS OF CAMBODIA TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................................................... 160 I. RWANDA AND THE GACACA COURT ....................................... 164 A. Formation .................................................................... 164 B. Structure ...................................................................... 165 C. Categories of Crimes .................................................. 166 D. Procedural Methods and Problems ............................ 168 II. THE EXTRAORDINARY CHAMBERS IN THE COURTS OF CAMBODIA ....................................................................... 170 A. Formation ................................................................... 170 B. Structure ..................................................................... 172 C. Administrative Divisions of the Court ........................ 173 1. Support for the Victims During the Process ........ 173 2. Access to Legal Counsel for Defendants ............. 174 3. A Central Office that Provides Support and Stability ................................................................ 175 D. Procedural Methods .................................................. 176 1. Role of the Victim ................................................ -

Rstc Meeting, Trat, Thailand Project Co-Ordinating Unit 1

SEAFDEC/UN Environment/GEF/FR-RSTC.1 INF.1 Regional Scientific and Technical Committee Meeting for the SEAFDEC/UN Environment/GEF Project on Establishment and Operation of a Regional System of Fisheries Refugia in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand 11th – 13th September 2018 Centara Chaan Talay Resort & Villas, Trat Province, Thailand Logistic Information for Participants QUICK LINKS (Click on title) to directly access the relevant text in this document Meeting Venue Accommodation Transportation Registration Weather Currency and DSA Meal Wi-Fi Visa Requirements Time Zone Electricity Health Fisheries Refugia Sites Other Information Local Contact Point RSTC MEETING, TRAT, THAILAND PROJECT CO-ORDINATING UNIT 1 SEAFDEC/UN Environment/GEF/FR-RSTC.1 INF.1 Dear Participants, Welcome to Thailand! To facilitate your travel preparations, please find below the information on logistic arrangements. 1. Meeting Venue The events will be held at the Centara Chaan Talay Resort & Villas Trat (Krissana Hall). Address: 4/2 Moo 9, Tambol Laem Klud, Amphur Muang, 23000 Phone: +66 (0) 3952 1561 -70, (0) 90 880 0248 Fax: +66 (0) 3952 1563 E-mail: [email protected] Location Map: The resort is 5 hours drive from Suvarnabhumi International Airport in Bangkok. Located 40 minutes from Trat town, in Thailand’s south-eastern province bordering on Cambodia with Khao Banthat Mountain range as a natural demarcation. *venue pictures from: https://www.centarahotelsresorts.com/centara/cct/ RSTC MEETING, TRAT, THAILAND PROJECT CO-ORDINATING UNIT 2 SEAFDEC/UN Environment/GEF/FR-RSTC.1 INF.1 2. Accommodation The organizers will take the responsibility for booking and paying for accommodation cost of the representative which cover room charge (single room) with Breakfast only. -

EDUCATION KNOWS NO BORDER: a COLLECTION of GOOD PRACTICES and LESSONS LEARNED on MIGRANT EDUCATION in THAILAND © UNICEF Thailand/2019/Keenapan ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

CONTACT US Facebook: facebook.com/unicefthailand Twitter: twitter.com/unicef_thailand UNICEF Thailand IG: @UNICEF_Thailand LINE: UNICEF Thailand EDUCATION KNOWS 19 Phra Atit Road Pranakorn, Bangkok 10200 Youtube: youtube.com/unicefthailand Thailand Website: www.unicef.or.th NO BORDER: Telephone: +66 2 356 9499 To donate Fax: +66 2 281 6032 Phone: +66 2 356 9299 A COLLECTION OF GOOD PRACTICES AND Email: [email protected] Fax: +66 2 356 9229 Email: [email protected] LESSONS LEARNED ON MIGRANT EDUCATION IN THAILAND This publication was produced with the financial support of the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of UNICEF and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union. The presentation of data and information as contained in this publication, and the opinions expressed therein, do not necessarily reflect the position of UNICEF. UNICEF is committed to widely disseminating information and to this end welcomes enquiries for reprints, adaptations, republishing or translating this or other publications. Cover photo: © UNICEF Thailand/2019/Apikul EDUCATION KNOWS NO BORDER: A COLLECTION OF GOOD PRACTICES AND LESSONS LEARNED ON MIGRANT EDUCATION IN THAILAND © UNICEF Thailand/2019/Keenapan ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Education Knows No Border: A Collection of Good Practices and Lessons Learned on Migrant Education in Thailand was commissioned as part of the “Protecting children affected by migration” – a project implemented by UNICEF Thailand and co-funded by the European Union and UNICEF. The publication contributes to the Programme Objective that Children affected by migration, including those trafficked, benefit from an enhanced enabling environment (policies and procedures) that provides better access to child protection systems, through the development, design, print and dissemination of a publication documenting good practices at the school and local education authority levels, addressing barriers to enrolment for migrant children and the quality of their education. -

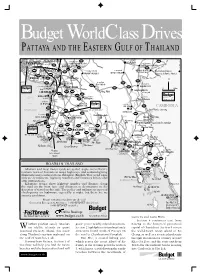

Budgetworldclassdrives

Budget WorldClass Drives PATTAYA AND THE EASTERN GULF OF THAILAND √–·°â« BANG NAM PRIED Õ.æπ¡ “√§“¡ 319 348 PHANOM SARAKHAM SA KAEO Õ.«—≤π“π§√ BANGKOK Õ.∫“ßπÈ”‡ª√’Ȭ« 304 Õ.∫“ߧ≈â“ BANG KHLA WATTHANA NAKHON 3245 33 3121 9 CHACHOENGSAO 304 Õ. π“¡™—¬‡¢µ Õ.‡¢“©°√√®å ARANYAPRATHET International Border Oliver Hargreave ©–‡™‘߇∑√“ 304 KHA0 CHAKAN Õ.Õ√—≠ª√–‡∑» 7 SANAMCHAI KHET Crossing & Border Market 3268 BANG BO Õ.∫â“π‚æ∏‘Ï 34 BAN PHO BANG PHLI Õ.∫“ß∫àÕ PLAENG YAO N Õ.∫“ßæ≈’ Õ.·ª≈߬“« 3395 Õ.æ“π∑Õß ∑à“µ–‡°’¬∫ 3 PHAN THONG 3434 Õ.§≈ÕßÀ“¥ 3259 THA TAKIAP Õ.∫“ߪ–°ß BANG PHANAT NIKHOM 3067 KHLONG HAT PAKONG 3259 0 20km ™≈∫ÿ√’ Õ.æπ— π‘§¡ WANG SOMBUN CHONBURI 349 331 Nong Khok Õ.«—ß ¡∫Ÿ√≥å 344 3245 BANG SAEN 3340 Õ.∫àÕ∑Õß G U L F BAN BUNG ∫.∑ÿàߢπ“π ∫“ß· π Õ.∫â“π∫÷ß 3401 BO THONG Thung Khanan Õ.»√’√“™“ O F SI RACHA Õ.ÀπÕß„À≠à Õ. Õ¬¥“« NONG YAI SOI DAO 3406 C A M B O D I A 3 T H A I L A N D 3138 3245 Tel: (0) 3895 4352 Local border crossing 7 Soi Dao Falls 344 317 Õ.∫“ß≈–¡ÿß 2 Bo Win Õ.ª≈«°·¥ß Khao Chamao Falls BAN LAMUNG PLUAK DAENG Khlong Pong Nam Ron Rafting Ko Lan Krathing 1 Khao Wong PONG NAM RON Local border crossing 3191 WANG CHAN 3377 Õ.‚ªÉßπÈ”√âÕπ Pattaya City 3 36 3471 «—ß®—π∑√å Õ.∫â“π©“ß Õ.∫â“π§à“¬ Õ.·°≈ß Khiritan Dam 3143 KLAENG BAN CHANG BAN KHAI 4 3 3138 3220 Tel: (0) 3871 0717-8 3143 MAKHAM Ko Khram √–¬Õß Õ.¡–¢“¡ Ban Noen RAYONG ®—π∑∫ÿ√’ Tak Daet SATTAHIP 3 Ban Phe Laem Õ.∑à“„À¡à Õ.