Migrant-Friendly.Pdf (11.62Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Budgetworldclass Drives

Budget WorldClass Drives Chiang Mai-Sukhothai Loop a m a z i n g 1998 Tourism Authority of Thailand (TAT) SELF DRIVE VACATIONS THAILAND 1999 NORTHERN THAILAND : CHIANG MAI - SUKHOTHAI AND BURMESE BORDERLANDS To Mae Hong Son To Fang To Chiang Rai To Wang Nua To Chiang Rai 1001 1096 1 107 KHUN YUAM 118 1317 1 SAN KAMPHAENG 1269 19 CHIANG MAI1006 MAE ON 1317 CHAE HOM HANG DONG SARAPHI 108 Doi Inthanon 106 SAN PA TONG 11 LAMPHUN 1009 108 116 MAE CHAEM 103 1156 PA SANG 1035 1031 1033 18 MAE THA Thung Kwian MAE LA NOI 11 Market 1088 CHOM TONG 1010 1 108 Thai Elephant HANG CHAT BAN HONG 1093 Conservation 4 2 1034 Centre 3 LAMPANG 11 To 106 1184 Nan 15 16 HOD Wat Phrathat 1037 LONG 17 MAE SARIANG 108 Lampang Luang KO KHA 14 MAE 11 PHRAE km.219 THA Ban Ton Phung 1103 THUNG 1 5 SUNGMEN HUA SOEM 1099 DOI TAO NGAM 1023 Ban 1194 SOP MOEI CHANG Wiang Kosai DEN CHAI Mae Sam Laep 105 1274 National Park WANG CHIN km.190 Mae Ngao 1125 National Park 1124 LI SOP PRAP OMKOI 1177 101 THOEN LAP LAE UTTARADIT Ban Tha 102 Song Yang Ban Mae Ramoeng MAE SI SATCHANALAI PHRIK 1294 Mae Ngao National Park 1305 6 Mae Salit Historical 101 km.114 11 1048 THUNG Park SAWAN 105 SALIAM 1113 7 KHALOK To THA SONG SAM NGAO 1113 Phitsa- YANG Bhumipol Dam Airport nuloke M Y A N M A R 1056 SI SAMRONG 1113 1195 Sukhothai 101 ( B U R M A ) 1175 9 Ban Tak Historical 1175 Ban 12 Phrathat Ton Kaew 1 Park BAN Kao SUKHOTHAI MAE RAMAT 12 DAN LAN 8 10 105 Taksin 12 HOI Ban Mae Ban National Park Ban Huai KHIRIMAT Lamao 105 TAK 1140 Lahu Kalok 11 105 Phrathat Hin Kiu 13 104 1132 101 12 Hilltribe Lan Sang Miyawadi MAE SOT Development National Park Moei PHRAN KRATAI Bridge 1090 Centre 1 0 10 20 kms. -

Rstc Meeting, Trat, Thailand Project Co-Ordinating Unit 1

SEAFDEC/UN Environment/GEF/FR-RSTC.1 INF.1 Regional Scientific and Technical Committee Meeting for the SEAFDEC/UN Environment/GEF Project on Establishment and Operation of a Regional System of Fisheries Refugia in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand 11th – 13th September 2018 Centara Chaan Talay Resort & Villas, Trat Province, Thailand Logistic Information for Participants QUICK LINKS (Click on title) to directly access the relevant text in this document Meeting Venue Accommodation Transportation Registration Weather Currency and DSA Meal Wi-Fi Visa Requirements Time Zone Electricity Health Fisheries Refugia Sites Other Information Local Contact Point RSTC MEETING, TRAT, THAILAND PROJECT CO-ORDINATING UNIT 1 SEAFDEC/UN Environment/GEF/FR-RSTC.1 INF.1 Dear Participants, Welcome to Thailand! To facilitate your travel preparations, please find below the information on logistic arrangements. 1. Meeting Venue The events will be held at the Centara Chaan Talay Resort & Villas Trat (Krissana Hall). Address: 4/2 Moo 9, Tambol Laem Klud, Amphur Muang, 23000 Phone: +66 (0) 3952 1561 -70, (0) 90 880 0248 Fax: +66 (0) 3952 1563 E-mail: [email protected] Location Map: The resort is 5 hours drive from Suvarnabhumi International Airport in Bangkok. Located 40 minutes from Trat town, in Thailand’s south-eastern province bordering on Cambodia with Khao Banthat Mountain range as a natural demarcation. *venue pictures from: https://www.centarahotelsresorts.com/centara/cct/ RSTC MEETING, TRAT, THAILAND PROJECT CO-ORDINATING UNIT 2 SEAFDEC/UN Environment/GEF/FR-RSTC.1 INF.1 2. Accommodation The organizers will take the responsibility for booking and paying for accommodation cost of the representative which cover room charge (single room) with Breakfast only. -

EDUCATION KNOWS NO BORDER: a COLLECTION of GOOD PRACTICES and LESSONS LEARNED on MIGRANT EDUCATION in THAILAND © UNICEF Thailand/2019/Keenapan ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

CONTACT US Facebook: facebook.com/unicefthailand Twitter: twitter.com/unicef_thailand UNICEF Thailand IG: @UNICEF_Thailand LINE: UNICEF Thailand EDUCATION KNOWS 19 Phra Atit Road Pranakorn, Bangkok 10200 Youtube: youtube.com/unicefthailand Thailand Website: www.unicef.or.th NO BORDER: Telephone: +66 2 356 9499 To donate Fax: +66 2 281 6032 Phone: +66 2 356 9299 A COLLECTION OF GOOD PRACTICES AND Email: [email protected] Fax: +66 2 356 9229 Email: [email protected] LESSONS LEARNED ON MIGRANT EDUCATION IN THAILAND This publication was produced with the financial support of the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of UNICEF and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union. The presentation of data and information as contained in this publication, and the opinions expressed therein, do not necessarily reflect the position of UNICEF. UNICEF is committed to widely disseminating information and to this end welcomes enquiries for reprints, adaptations, republishing or translating this or other publications. Cover photo: © UNICEF Thailand/2019/Apikul EDUCATION KNOWS NO BORDER: A COLLECTION OF GOOD PRACTICES AND LESSONS LEARNED ON MIGRANT EDUCATION IN THAILAND © UNICEF Thailand/2019/Keenapan ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Education Knows No Border: A Collection of Good Practices and Lessons Learned on Migrant Education in Thailand was commissioned as part of the “Protecting children affected by migration” – a project implemented by UNICEF Thailand and co-funded by the European Union and UNICEF. The publication contributes to the Programme Objective that Children affected by migration, including those trafficked, benefit from an enhanced enabling environment (policies and procedures) that provides better access to child protection systems, through the development, design, print and dissemination of a publication documenting good practices at the school and local education authority levels, addressing barriers to enrolment for migrant children and the quality of their education. -

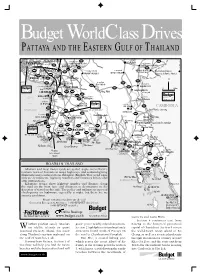

Budgetworldclassdrives

Budget WorldClass Drives PATTAYA AND THE EASTERN GULF OF THAILAND √–·°â« BANG NAM PRIED Õ.æπ¡ “√§“¡ 319 348 PHANOM SARAKHAM SA KAEO Õ.«—≤π“π§√ BANGKOK Õ.∫“ßπÈ”‡ª√’Ȭ« 304 Õ.∫“ߧ≈â“ BANG KHLA WATTHANA NAKHON 3245 33 3121 9 CHACHOENGSAO 304 Õ. π“¡™—¬‡¢µ Õ.‡¢“©°√√®å ARANYAPRATHET International Border Oliver Hargreave ©–‡™‘߇∑√“ 304 KHA0 CHAKAN Õ.Õ√—≠ª√–‡∑» 7 SANAMCHAI KHET Crossing & Border Market 3268 BANG BO Õ.∫â“π‚æ∏‘Ï 34 BAN PHO BANG PHLI Õ.∫“ß∫àÕ PLAENG YAO N Õ.∫“ßæ≈’ Õ.·ª≈߬“« 3395 Õ.æ“π∑Õß ∑à“µ–‡°’¬∫ 3 PHAN THONG 3434 Õ.§≈ÕßÀ“¥ 3259 THA TAKIAP Õ.∫“ߪ–°ß BANG PHANAT NIKHOM 3067 KHLONG HAT PAKONG 3259 0 20km ™≈∫ÿ√’ Õ.æπ— π‘§¡ WANG SOMBUN CHONBURI 349 331 Nong Khok Õ.«—ß ¡∫Ÿ√≥å 344 3245 BANG SAEN 3340 Õ.∫àÕ∑Õß G U L F BAN BUNG ∫.∑ÿàߢπ“π ∫“ß· π Õ.∫â“π∫÷ß 3401 BO THONG Thung Khanan Õ.»√’√“™“ O F SI RACHA Õ.ÀπÕß„À≠à Õ. Õ¬¥“« NONG YAI SOI DAO 3406 C A M B O D I A 3 T H A I L A N D 3138 3245 Tel: (0) 3895 4352 Local border crossing 7 Soi Dao Falls 344 317 Õ.∫“ß≈–¡ÿß 2 Bo Win Õ.ª≈«°·¥ß Khao Chamao Falls BAN LAMUNG PLUAK DAENG Khlong Pong Nam Ron Rafting Ko Lan Krathing 1 Khao Wong PONG NAM RON Local border crossing 3191 WANG CHAN 3377 Õ.‚ªÉßπÈ”√âÕπ Pattaya City 3 36 3471 «—ß®—π∑√å Õ.∫â“π©“ß Õ.∫â“π§à“¬ Õ.·°≈ß Khiritan Dam 3143 KLAENG BAN CHANG BAN KHAI 4 3 3138 3220 Tel: (0) 3871 0717-8 3143 MAKHAM Ko Khram √–¬Õß Õ.¡–¢“¡ Ban Noen RAYONG ®—π∑∫ÿ√’ Tak Daet SATTAHIP 3 Ban Phe Laem Õ.∑à“„À¡à Õ. -

Notification of the Central Committee on the Price of Goods and Services No

Notification of the Central Committee on the Price of Goods and Services No. 4, B.E. 2560 (2017) Regarding Control of Transport of Paddy, Rice ------------------------------------ Whereas the Central Committee on the Price of Goods and Services has repealed the Notification of the Central Committee on the Price of Goods and Services No. 1, B.E. 2559 (2016) regarding Determination of Goods and Services under Control dated 21 January B.E. 2559 ( 2016) , resulting in the end of enforcement of the Notification of the Central Committee on the Price of Goods and Services No. 4, B.E. 2559 (2016) regarding Control of Transport of Paddy, Rice dated 25 January B.E. 2559 (2016). In the meantime, the Central Committee on the Price of Goods and Services has already reconsidered the exercise of its power regarding the stipulation of the aforesaid measure, it is of the view that the measure of the control of transport of paddy, rice should be maintained in order to bring about the fairness of price, quantity and the maintenance of stability of the rice market system within the Kingdom. By virtue of Section 9 (2) and Section 25 (4), (7) of the Price of Goods and Services Act, B.E. 2542 ( 1999) , the Central Committee on the Price of Goods and Services has therefore issued this Notification, as follows. Article 1. This Notification shall come into force in all areas of the Kingdom for the period of one year as from the day following the date of its publication.1 Article 2. In this Notification, “rice” means rice, pieces of rice, broken-milled rice. -

Usaid Thailand Counter Trafficking in Persons Quarterly Performance Report April - June 2019

USAID THAILAND COUNTER TRAFFICKING IN PERSONS QUARTERLY PERFORMANCE REPORT APRIL - JUNE 2019 Cooperative Agreement No. AID-486-LA-17-00001 Submitted to United States Agency for International Development Regional Development Mission for Asia Submitted by Winrock International 2121 Crystal Drive Arlington, Virginia 22202 30 July 2019 chReview/USAID Thailand CTIP FY2019 Q3 Quarterly Performance Report USAID THAILAND COUNTER TRAFFICKING IN PERSONS QUARTERLY PERFORMANCE REPORT APRIL - JUNE 2019 DISCLAIMER The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations ....................................................................................................................................................................... i I. Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................................... iv II. Project Description ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 III. Summary of Activities ............................................................................................................................................... 2 A. Project Management and Administration ....................................................................................................... 2 B. -

Assessment of Greater Mekong Subregion Economic Corridors

About the Assessment of Greater Mekong Subregion Economic Corridors The transformation of transport corridors into economic corridors has been at the center of the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS) Economic Cooperation Program since 1998. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) conducted this Assessment to guide future investments and provide benchmarks for improving the GMS economic corridors. This Assessment reviews the state of the GMS economic corridors, focusing on transport infrastructure, particularly road transport, cross-border transport and trade, and economic potential. This assessment consists of six country reports and an integrative report initially presented in June 2018 at the GMS Subregional Transport Forum. About the Greater Mekong Subregion Economic Cooperation Program The GMS consists of Cambodia, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Myanmar, the People’s Republic of China (specifically Yunnan Province and Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region), Thailand, and Viet Nam. In 1992, with assistance from the Asian Development Bank and building on their shared histories and cultures, the six countries of the GMS launched the GMS Program, a program of subregional economic cooperation. The program’s nine priority sectors are agriculture, energy, environment, human resource development, investment, telecommunications, tourism, transport infrastructure, and transport and trade facilitation. About the Asian Development Bank ADB is committed to achieving a prosperous, inclusive, resilient, and sustainable Asia and the Pacific, while sustaining -

Tax & Legal Services Newsletter

Tax & Legal Services Newsletter Vol. September 2014 ๖ Proposal for 10-Year Corporate Income Tax Exemption for Special Economic Zones The Ministry of Finance is considering the granting of incentives in the form of a tax exemption to five special economic zones established by the National Council for Peace and Order. The affected zones are the Mae Sot district in Tak province, the Aranyaprathet district in Sa Kaeo province, the Khlong Yai district in Trat province, Mukdahan province and the Sadao district in Songkhla province. The incentives would be granted more favorable treatment than incentives in Zone 3 currently granted by the Thailand Board of Investment (e.g. a 8-year exemption from corporate income tax with 50% reduction for another 3- 5 years) in order to promote investment in the above zones. Studies of Negative Income Tax The Fiscal Policy Office of the Ministry of Finance has released a study of negative income tax. According to a proposal in the study, the government would provide assistance to low income individuals, i.e. individuals who earn income below THB 30,000 would receive a payment from the government in an amount equal to 20% of their annual income. The payment would decrease as income rises and cease once income exceeds THB 80,000. If the initiative is approved, the government would use information provided in the personal income tax return to determine whether an individual qualifies for the payment. Revenue Department Rulings Specific Business Tax Treatment of Intercompany Guarantee Company A, a major shareholder of Company B, shares a board of directors with Company B. -

Precaution Praised As Ban on Boats Leaving Shore Enforced Amid Pabuk Fallout

THEPHUKETNEWS.COM FRIDAY, JANUARY 11, 2019 thephuketnews thephuketnews1 thephuketnews.com Friday, January 11 – Thursday, January 17, 2019 Since 2011 / Volume IX / No. 2 20 Baht FISHING FLEET DODGES ECONOMIC HIT > PAGE 9 NEWS PAGE 4 Island readies for mass fun on Children’s Day LIFE PAGE 11 SAFETY Using Eco-Logic: New trends in voluntourism A tour boat returns to Phuket with hundreds of tourists who were stranded on Phi Phi Island. Photo: PR Dept FIRST PRECAUTION PRAISED AS BAN ON BOATS LEAVING SHORE ENFORCED AMID PABUK FALLOUT The Phuket News No reports of serious damage or on high alert. Emergency services the ‘Phuket Model’ format as a work [email protected] landslides were recorded anywhere were on standby and Phuket Gov- guide for coping with all kinds of across Phuket. ernor Phakaphong Tavipatana last disasters and future events as well, PAGE 32 eople across Phuket breathed Nakhon Sri Thammarat on South- Wednesday (Jan 5) ordered local which requires the integration of the SPORT a collective sigh of relief last ern Thailand’s east coast, however, authorities to take steps to ensure that work of all sectors in order to help Pweekend when the worst of suffered greatly with winds belting up essential services such as electricity the people and for tourists to have Darren to ‘bike Tropical Storm Pabuk missed the to 89km/h and a monstrous 270.5mm supply remained available. maximum security,” he added. island entirely. By that time Pabuk of rainfall recorded in just the 24 hours “In this operation, to be prepared However, by then the news of Everest’ for had already been downgraded to a of last Friday (Jan 4). -

Usaid Thailand Counter Trafficking in Persons Annual Report October 1, 2018 - September 30, 2019

USAID THAILAND COUNTER TRAFFICKING IN PERSONS ANNUAL REPORT OCTOBER 1, 2018 - SEPTEMBER 30, 2019 COOPERATIVE AGREEMENT NUMBER: AID-486-LA-17-00001 Submitted to United States Agency for International Development Regional Development Mission for Asia Submitted by Winrock International 2121 Crystal Drive Arlington, Virginia 22202 October 30, 2019 chReview/ USAID Thailand CTIP, Year 2 Annual Report USAID THAILAND COUNTER TRAFFICKING IN PERSONS ANNUAL REPORT OCTOBER 2018- SEPTEMBER 2019 DISCLAIMER The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations ....................................................................................................................................................................... i I. Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................................... 1 II. Project Description ....................................................................................................................................................... 2 III. Highlights and Key Achivements ........................................................................................................................... 3 A. Project Management and Administration ....................................................................................................... 5 B. Key Project Deliverables -

Afghanistan Bangladesh

PACIFIC DISASTER MANAGEMENT INFORMATION NETWORK (PDMIN) 1 Jarrett White Road MCPA-DM, Tripler AMC, HI 96859-5000 Telephone: 808.433.7035 · [email protected] · http://www.coe-dmha.org Asia-Pacific Daily Report April 12, 2004 Afghanistan Afghan government to send more troops to northwestern Faryab province following factional clashes over the weekend The Afghan central government of President Hamid Karzai is sending some 200 additional troops to Afghanistan’s northwestern Faryab province following new skirmishes between rival factions in the area. Mohammad Shafi, a local commander, told the United Nations Integrated Regional Information Network (IRIN) that a small skirmish between fighters loyal to ethnic Uzbek warlord General Abdul Rashid Dostum and that of his Tajik rival, Atta Mohammad, took place on Saturday (April 10) in Kod-i-Barq town, some 12 miles (20 kilometers) from the northern city of Mazar-i-Sharif in Balkh province. Following the incident which left several people wounded, schools and other public institutions were reportedly closed in Kod-i-Barq. Lutfullah Mashal, spokesman for the Afghan Interior Ministry, told IRIN that the situation in the provincial capital Maimana (also spelled Maymana) of Faryab province, which was overrun by Dostum’s troops last Tuesday (April 6), was calm and that some 500 troops from the Afghan National Army (ANA) were in control of Maimana. Manoel de Almedia e Silva, spokesman for the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) told a press briefing yesterday that the situation in Maimana and Faryab in general was calm with no reports of further unrest since last Thursday (April 8). -

Strengthening Sustainable Tourism

Strengthening Sustainable Tourism Strategic Environmental Assessment of the Tourism Sector in Cambodia Strategic Environmental Assessment of the Tourism Sector in Cambodia The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank, or its Board of Governors or the governments they represent. The Asian Development Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequences of their use. Use of the term “country” does not imply any judgment by the authors or the Asian Development Bank as to the legal or other status of any territorial entity. Copyright © 2009 Asian Development Bank Report authors: Peter King, Robert Basiuk, Bou Serey Chan and Dararath Yem Project management: Pavit Ramachandran, GMS-EOC Maps and spatial analysis: Lothar Linde, GMS-EOC Cover photos and photo credits: Stephen Griffiths, ADB; GMS-EOC Design and layout: Keen Media (Thailand) Co., Ltd. GMS Environment Operations Center The Offices at Central World, 23rd Floor 999/9 Rama I Road, Pathumwan Bangkok 10330, Thailand Tel: +66 2 207 4444 Fax: +66 2 207 4400 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.gms-eoc.org Contents List of Tables v List of Figures vi Acronyms and Abbreviations vii Notes ix Executive Summary x 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Socio-Economic Context 1 1.2 SEA Scoping Stage 2 2. Tourism Sector in Cambodia 3 2.1 Tourism Sector and the Economy 3 2.2 National Tourism Strategy Plans and Policies 7 2.3 Tourism Laws and Regulations 16 2.4 Institutions in Cambodia with Tourism-related Responsibilities 18 2.5 Tourism Plans in Northeast Cambodia 22 2.6 Tourism Plans in Southwest Cambodia 28 3.