Art, Ritual, and Reform: the Archconfraternity of the Holy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parish Apostolate: New Opportunities in the Local Church

IV. PARISH APOSTOLATE: NEW OPPORTUNITIES IN THE LOCAL CHURCH by John E. Rybolt, C.M. Beginning with the original contract establishing the Community, 17 April 1625, Vincentians have worked in parishes. At fIrst they merely assisted diocesan pastors, but with the foundation at Toul in 1635, the fIrst outside of Paris, they assumed local pastorates. Saint Vincent himself had been the pastor of Clichy-Ia-Garenne near Paris (1612-1625), and briefly (1617) of Buenans and Chatillon les-Dombes in the diocese of Lyons. Later, as superior general, he accepted eight parish foundations for his community. He did so with some misgiving, however, fearing the abandonment of the country poor. A letter of 1653 presents at least part of his outlook: ., .parishes are not our affair. We have very few, as you know, and those that we have have been given to us against our will, or by our founders or by their lordships the bishops, whom we cannot refuse in order not to be on bad terms with them, and perhaps the one in Brial is the last that we will ever accept, because the further along we go, the more we fmd ourselves embarrassed by such matters. l In the same spirit, the early assemblies of the Community insisted that parishes formed an exception to its usual works. The assembly of 1724 states what other Vincentian documents often said: Parishes should not ordinarily be accepted, but they may be accepted on the rare occasions when the superior general .. , [and] his consul tors judge it expedient in the Lord.2 229 Beginnings to 1830 The founding document of the Community's mission in the United States signed by Bishop Louis Dubourg, Fathers Domenico Sicardi and Felix De Andreis, spells out their attitude toward parishes in the new world, an attitude differing in some respects from that of the 1724 assembly. -

The Archconfraternity of the Most Precious Blood

The Archconfraternity of the Most Precious Blood By Francesco Bartoloni, cpps I should like to begin by noting that in preparing this presentation I have relied heavily on Michele Colagiovanni’s, Il Padre Segreto, Vita di Monsignore Francesco Albertini, especially chapters 10, 11, 12, and 18, and an article by Mario Dariozzi, cpps, “L’Arciconfraternità del Preziossissimo Sangue in San Nicola in Carcere Tulliano.” (See the end of the article for full references.) The Enciclopedia Cattolica defines a confraternity as an ecclesiastical corporation, composed primarily of the laity, canonically erected and governed by a competent superior, with the aim of promoting the Christian faith by means of special good works directed to divine worship or to charity to one’s neighbor. Often worship and charity are associated aims in the statutes of confraternities. Thus conceived, they are genuine and stable ecclesiastical foundations with their own organization, capable of having their own statutes, etc. According to the Code of Canon Law of 1917, confraternities are not to be confused with: 1. those institutes that have the title of “pious causes” (hospitality, recovery houses, orphanages, etc.) which have a more complex aim; 2. pious unions that exist for a particular occasion, held together by the will of their members, which go out of existence when there are no more members; 3. secular third orders that are closely linked with the religious order from which they derive their name; 4. associations of the arts and of craftsmen which have an aim that is primarily economic, even if they place themselves under the protection of a saint. -

Acollection of Correspondence

© 2012 Capuchin Friars of Australia. All Rights Reserved. A COLLECTION OF CORRESPONDENCE Some Letters … and other things, from Sixteenth Century Italy in their original languages Bernardo, ben potea bastarvi averne Co’l dolce dir, ch’a voi natura infonde, Qui dove ‘l re de’ fiume ha più chiare onde, Acceso i cori a le sante opre eterne; Ché se pur sono in voi pure l’interne Voglie, e la vita al destin corrisponde, Non uom di frale carne e d’ossa immonde, Ma sète un voi de le schiere sperne. Or le finte apparenze, e ‘l ballo, e ‘l suono, Chiesti dal tempo e da l’antica usanza, A che così da voi vietate sono? Non fôra santità,capdox fôra arroganza Tôrre il libero arbitrio, il maggior dono Che Dio ne diè ne la primera stanza.1 Compiled by Paul Hanbridge Fourth edition, formerly “A Sixteenth Century Carteggio” Rome, 2007, 2008, Dec 2009 1 “Bernardo, it should be enough for you / With that sweet speech infused in you by Nature, / To light our hearts to high eternal works, / Here where the King of Rivers flows most clearly. / Since your own inner wishes are sincere, / And your own life reflects a pure intent, / You’re ra- ther an inhabitant of heaven. /As to these masquerades, dances, and music, /Sanctioned by time and by ancient custom - /Why do you now forbid them in your sermons? /Holiness it is not, but arrogance to take away free will, the highest gift/ Which God bestowed on us from the begin- ning.” Tullia d’Aragona (c. -

Troubadour Tales

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES EDWARD- S- SULLIVAN Troubadour Tales Troubadour Tales By Evaleen Stein With Illustrations By Virginia Keep Maxfield Parrish B. Rosenmeyer &? Edward Edwards Indianapolis The Bobbs-Merrill Company Publishers Copyright 1903 The Bobbs-Merrill Company ~Jdy~ Printed in the United States of America PRESS OF RRAUNWORTH It CO. BOOK MANUFACTURER* BROOKLYN, N. Y. To My Mother 631959 Contents THE PAGE OF COUNT REYNAURD i THE LOST RUNE 27 COUNT HUGO'S SWORD 76 FELIX I3 2 Troubadour Tales THE PAGE OF COUNT REYNAURD HOW HE EARNED THE FAVOR OF KING RENE AND WON A SILVER CUP FOR CLEVERNESS IN THE LATIN TONGUE " PIERROT! Pierrot! are thy saddle-bags well fastened ? And how fare my lutestrings ? Have a care lest some of them snap with jog ging over this rough bit of road. And, Pierrot, next time we pass a fine periwinkle thou hadst best jump down and pluck a fresh bunch for my Barbo's ears." The speaker, Count Reynaurd of Poitiers, patted the fluffy black mane of his horse Barbo, and loosened the great nosegay of blue flowers 2 TROUBADOUR TALES tucked into his harness and nodding behind his ears. Barbo was gaily decked out; long sprays of myrtle dangled from his saddle-bow, and a wreath of periwinkle and violets hung round his neck for the Count was not ; Reynaurd only a noble lord, but also a famous troubadour. That is to say, he spent his time riding from castle to castle, playing on his lute or viol, and singing beautiful songs of his own making. -

Observing Protest from a Place

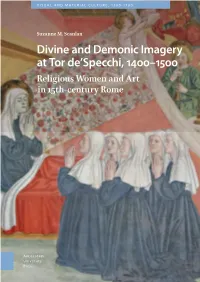

VISUAL AND MATERIAL CULTURE, 1300-1700 Suzanne M. Scanlan M. Suzanne Suzanne M. Scanlan Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Religious Women and Art in 15th-century Rome at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 de’Specchi, Tor at Divine and Demonic Imagery Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 A forum for innovative research on the role of images and objects in the late medieval and early modern periods, Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 publishes mono- graphs and essay collections that combine rigorous investigation with critical inquiry to present new narratives on a wide range of topics, from traditional arts to seeming- ly ordinary things. Recognizing the fluidity of images, objects, and ideas, this series fosters cross-cultural as well as multi-disciplinary exploration. We consider proposals from across the spectrum of analytic approaches and methodologies. Series Editor Dr. Allison Levy, an art historian, has written and/or edited three scholarly books, and she has been the recipient of numerous grants and awards, from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the American Association of University Women, the Getty Research Institute, the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library of Harvard University, the Whiting Foundation and the Bogliasco Foundation, among others. www.allisonlevy.com. Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Religious Women and Art in Fifteenth-Century Rome Suzanne M. Scanlan Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Attributed to Antoniazzo Romano, The Death of Santa Francesca Romana, detail, fresco, 1468, former oratory, Tor de’Specchi, Rome. Photo by Author with permission from Suor Maria Camilla Rea, Madre Presidente. -

The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions

Center for Basque Studies Basque Classics Series, No. 6 The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions by Philippe Veyrin Translated by Andrew Brown Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada This book was published with generous financial support obtained by the Association of Friends of the Center for Basque Studies from the Provincial Government of Bizkaia. Basque Classics Series, No. 6 Series Editors: William A. Douglass, Gregorio Monreal, and Pello Salaburu Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada 89557 http://basque.unr.edu Copyright © 2011 by the Center for Basque Studies All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Cover and series design © 2011 by Jose Luis Agote Cover illustration: Xiberoko maskaradak (Maskaradak of Zuberoa), drawing by Paul-Adolph Kaufman, 1906 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Veyrin, Philippe, 1900-1962. [Basques de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre. English] The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre : their history and their traditions / by Philippe Veyrin ; with an introduction by Sandra Ott ; translated by Andrew Brown. p. cm. Translation of: Les Basques, de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: “Classic book on the Basques of Iparralde (French Basque Country) originally published in 1942, treating Basque history and culture in the region”--Provided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-877802-99-7 (hardcover) 1. Pays Basque (France)--Description and travel. 2. Pays Basque (France)-- History. I. Title. DC611.B313V513 2011 944’.716--dc22 2011001810 Contents List of Illustrations..................................................... vii Note on Basque Orthography......................................... -

40"" Anniversary of Del Verbum International Congress "Sacred Scripture in the Life of the Church" CATHOLIC BIBLICAL FEDERATION 4T

VERBUM ic Biblical Federation I I I I I } i V \ 40"" Anniversary of Del Verbum International Congress "Sacred Scripture in the Life of the Church" CATHOLIC BIBLICAL FEDERATION 4t BULLETIN DEI VERBUM is a quarterly publica tion in English, French, German and Spanish. Editors Alexander M. Schweitzer Glaudio EttI Assistant to the editors Dorothea Knabe Production and layout bm-projekte, 70771 Leinf.-Echterdingen A subscription for one year consists of four issues beginning the quarter payment is Dei Verbum Congress 2005 received. Please indicate in which language you wish to receive the BULLETIN DEI VERBUM. Summary Subscription rates ■ Ordinary subscription: US$ 201 €20 ■ Supporting subscription: US$ 34 / € 34 Audience Granted by Pope Benedict XVI « Third World countries: US$ 14 / € 14 ■ Students: US$ 14/€ 14 Message of the Holy Father Air mail delivery: US$ 7 / € 7 extra In order to cover production costs we recom mend a supporting subscription. For mem Solemn Opening bers of the Catholic Biblical Federation the The Word of God In the Life of the Church subscription fee is included in the annual membership fee. Greeting Address by the CBF President Msgr. Vincenzo Paglia 6 Banking details General Secretariat "Ut Dei Verbum currat" (Address as indicated below) LIGA Bank, Stuttgart Opening Address of the Exhibition by the CBF General Secretary A l e x a n d e r M . S c h w e i t z e r 1 1 Account No. 64 59 820 IBAN-No. DE 28 7509 0300 0006 4598 20 BIO Code GENODEF1M05 Or per check to the General Secretariat. -

A Revolution in Information?

A Revolution in Information? The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Blair, Ann, and Devin Fitzgerald. 2014. "A Revolution in Information?" In The Oxford Handbook of Early Modern European History, 1350-1750, edited by Hamish Scott, 244-65. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Published Version doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199597253.013.8 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:34334604 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Policy Articles, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#OAP Manuscript of Ann Blair and Devin Fitzgerald, "A Revolution in Information?" in the Oxford Handbook of Early Modern European History, ed. Hamish Scott (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), pp. 244-65. Chapter 10 A revolution in information?1 Ann Blair and Devin Fitzgerald The notion of a revolution in information in early modern Europe is a recent historiographical construct, inspired by the current use of the term to designate the transformations of the late 20th century. The notion, first propounded in the 1960s, that we live in an "information age" crucially defined by digital technologies for creating, storing, commoditizing, and disseminating information has motivated historians, especially since the late 1990s, to reflect on parallels with the past.2 Given the many definitions for "information" and related concepts, we will use the term in a nontechnical way, as distinct from data (which requires further processing before it can be meaningful) and from knowledge (which implies an individual knower). -

A Transcription and Translation of Ms 469 (F.101R – 129R) of the Vadianische Sammlung of the Kantonsbibliothek of St. Gallen

A SCURRILOUS LETTER TO POPE PAUL III A Transcription and Translation of Ms 469 (f.101r – 129r) of the Vadianische Sammlung of the Kantonsbibliothek of St. Gallen by Paul Hanbridge PRÉCIS A Scurrilous Letter to Pope Paul III. A Transcription and Translation of Ms 469 (f.101r – 129r) of the Vadianische Sammlung of the Kantonsbibliothek of St. Gallen. This study introduces a transcription and English translation of a ‘Letter’ in VS 469. The document is titled: Epistola invectiva Bernhardj Occhinj in qua vita et res gestae Pauli tertij Pont. Max. describuntur . The study notes other versions of the letter located in Florence. It shows that one of these copied the VS469, and that the VS469 is the earliest of the four Mss and was made from an Italian exemplar. An apocryphal document, the ‘Letter’ has been studied briefly by Ochino scholars Karl Benrath and Bendetto Nicolini, though without reference to this particular Ms. The introduction considers alternative contemporary attributions to other authors, including a more proximate determination of the first publication date of the Letter. Mario da Mercato Saraceno, the first official Capuchin ‘chronicler,’ reported a letter Paul III received from Bernardino Ochino in September 1542. Cesare Cantù and the Capuchin historian Melchiorre da Pobladura (Raffaele Turrado Riesco) after him, and quite possibly the first generations of Capuchins, identified the1542 letter with the one in transcribed in these Mss. The author shows this identification to be untenable. The transcription of VS469 is followed by an annotated English translation. Variations between the Mss are footnoted in the translation. © Paul Hanbridge, 2010 A SCURRILOUS LETTER TO POPE PAUL III A Transcription and Translation of Ms 469 (f.101r – 129r) of the Vadianische Sammlung of the Kantonsbibliothek of St. -

Pentecosttoday

Publication of the National Service Committee of the Catholic Charismatic Renewal PENTECOSTToda y January/February/March 2001 Volume 26, Number 1 NEW COLUMN! Spiritual Formation ALLED & GIFTED Growing in faith .......................................... 7 What is faith and how do we mature in it? In Cooperators in the work of the Lord ........ 3 this new regular feature, Dorothy Ranaghan The role of the laity has shifted dramatically reflects on the basics of our spiritual lives. since Vatican Council II. Walter Matthews takes a look at the impact of the Decree on C the Apostolate of Lay People thirty-five years LEADERS FOCUS after its publication. Gifts for the church or gifts Taking it to the streets ............................... 5 for the kingdom? ................................... 9 Josephine Cachia describes how the Dio- Fr. George Montague invites us to take cese of Brooklyn took the celebration of the another look at what the charisms are and Jubilee from the churches out into the world. why they have been given to the church. The soul of the world ................................. 6 The mission of Christ is carried out not just in Newsbriefs ................................................. 11 parish ministries and programs, but in busi- nesses and social structures as well. Deacon Chairman’s Corner 2 Friends of the NSC 15 Keith Fournier shares his experience of being called to mission in the secular world. From the Director 14 Ministry Update 15 Photo: The Tablet, Diocese of Brooklyn Tablet, The Photo: Renewing the grace of Pentecost in the life and mission of the church. ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ PENTECOSTToday Chairman s ○○○○○○ Corner○○○○○ Director by Fr. Patsy Iaquinta Walter C. J. Matthews Editorial Board Fr. -

Download PDF Datastream

DOORWAYS TO THE DEMONIC AND DIVINE: VISIONS OF SANTA FRANCESCA ROMANA AND THE FRESCOES OF TOR DE’SPECCHI BY SUZANNE M. SCANLAN B.A., STONEHILL COLLEGE, 2002 M.A., BROWN UNIVERSITY, 2006 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY OF ART AND ARCHITECTURE AT BROWN UNIVERSITY PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND MAY, 2010 © Copyright 2010 by Suzanne M. Scanlan ii This dissertation by Suzanne M. Scanlan is accepted in its present form by the Department of History of Art and Architecture as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Date_____________ ______________________________________ Evelyn Lincoln, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date______________ ______________________________________ Sheila Bonde, Reader Date______________ ______________________________________ Caroline Castiglione, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date______________ _____________________________________ Sheila Bonde, Dean of the Graduate School iii VITA Suzanne Scanlan was born in 1961 in Boston, Massachusetts and moved to North Kingstown, Rhode Island in 1999. She attended Stonehill College, in North Easton, Massachusetts, where she received her B.A. in humanities, magna cum laude, in 2002. Suzanne entered the graduate program in the Department of History of Art and Architecture at Brown University in 2004, studying under Professor Evelyn Lincoln. She received her M.A. in art history in 2006. The title of her masters’ thesis was Images of Salvation and Reform in Poccetti’s Innocenti Fresco. In the spring of 2006, Suzanne received the Kermit Champa Memorial Fund pre- dissertation research grant in art history at Brown. This grant, along with a research assistantship in Italian studies with Professor Caroline Castiglione, enabled Suzanne to travel to Italy to begin work on her thesis. -

Molto Più Di Una Vacanza

Molto più di una vacanza Gentile Ospite, a nome nostro e di tutto lo staff siamo lieti di porgerLe il più caloroso benvenuto e La ringraziamo di aver scelto il Giardinetto per soggiornare sul Lago d’Orta. La nostra casa è affacciata sulle acque del romantico lago d’Orta in un’oasi di tranquillità e relax. Siamo a pochi minuti dal centro di Orta San Giulio, dove scoprirà testimonianze storiche, artistiche e culturali. La invitiamo ad assaggiare la cucina mediterranea creativa e le specialità del nostro Ristorante, la nostra carta vini conta più di 300 etichette, italiane e non, per ogni piacevole occasione! Ci auguriamo che Lei possa trovare in questo luogo l’atmosfera di casa, la Sua tranquillità ed il Suo calore, con quel pizzico di charme in più che ci contraddistingue. Le ricordiamo inoltre che troverà a Sua disposizione piscina con acqua vitalizzata del circuito “Grander”, sdraio e ombrelloni per il Suo relax sul lago nonché la possibilità di praticare diversi sport acquatici. Dear Guest, on behalf of the staff and ourselves we have the pleasure of wishing you our warmest welcome and thank you for having chosen Hotel Giardinetto for your stay on Lake Orta. Our hotel is beautifully located in a romantic and quiet relaxing oasis. We are a few minutes away from Orta San Giulio where you can discover some of its history, art and culture. We invite you to taste the Mediterranean and creative local cuisine of our Restaurant, our great wine list has more than 300 labels for every special occasion! We hope that you can find here the same comfort you have at home, with the peaceful charm and warmth that sets us apart.