Download PDF Datastream

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Observing Protest from a Place

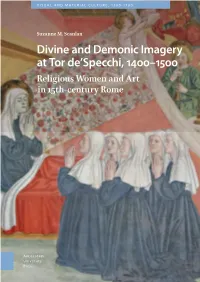

VISUAL AND MATERIAL CULTURE, 1300-1700 Suzanne M. Scanlan M. Suzanne Suzanne M. Scanlan Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Religious Women and Art in 15th-century Rome at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 de’Specchi, Tor at Divine and Demonic Imagery Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 A forum for innovative research on the role of images and objects in the late medieval and early modern periods, Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 publishes mono- graphs and essay collections that combine rigorous investigation with critical inquiry to present new narratives on a wide range of topics, from traditional arts to seeming- ly ordinary things. Recognizing the fluidity of images, objects, and ideas, this series fosters cross-cultural as well as multi-disciplinary exploration. We consider proposals from across the spectrum of analytic approaches and methodologies. Series Editor Dr. Allison Levy, an art historian, has written and/or edited three scholarly books, and she has been the recipient of numerous grants and awards, from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the American Association of University Women, the Getty Research Institute, the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library of Harvard University, the Whiting Foundation and the Bogliasco Foundation, among others. www.allisonlevy.com. Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Religious Women and Art in Fifteenth-Century Rome Suzanne M. Scanlan Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Attributed to Antoniazzo Romano, The Death of Santa Francesca Romana, detail, fresco, 1468, former oratory, Tor de’Specchi, Rome. Photo by Author with permission from Suor Maria Camilla Rea, Madre Presidente. -

Antonio Paolucci. Il Laico Che Custodisce I Tesori Del Papa

Trimestrale Data 06-2015 NUOVA ANTOLOGIA Pagina 178/82 Foglio 1 / 3 Italiani ANTONIO PAOLUCCI IL LAICO CHE CUSTODISCE I TESORI DEL PAPA Non e cambiato. All’imbrunire di una bella giornata d’inverno l’ho intravisto vicino al Pantheon. Si soffermava, osservava, scrutava gente e monumenti, come per anni gli avevo visto fare a Firenze, tra Palazzo Vecchio e Santa Croce. Si muoveva in modo dinoccolato, ma estremamente elegante e con autorevolezza. A Firenze il popolino e i bottegai lo salutavano con rispetto e con calore. A Roma, una frotta di turisti cinesi, senza sapere chi sia, gli fa spazio per farlo passare e il tono delle voci si abbassa. Ha un tratto e uno stile che lo distingue dagli altri, che lo fa notare. Dopo aver vissuto per anni a Firenze, Antonio Paolucci ora abita a Roma, ma ci sta da fi orentino. Cioè pronto a tornare sulle rive dell’Arno il venerdì sera e a riprendere il «Frecciarossa» il lunedì mattina. Dal 2007 lavora per l’ultimo monarca assoluto al mondo, che lo ha chiamato a curare una delle più importanti collezioni d’arte esistenti. La Bolla pontifi cia, fi rmata da Benedetto XVI, lo ha nominato, infatti, direttore dei Musei Vaticani. Paolucci considera questo incarico un «riconoscimento alla carriera». Un percorso lungo e glorioso per chi continua a defi nirsi un «tecnico della tutela». Classe 1939, nato a Rimini, nel 1969, dopo aver studiato a Firenze e Bologna, vince il concorso come ispettore delle Belle Arti. Inizia alla Soprintendenza di Firenze, poi nel 1980 diviene soprintendente di Venezia, quindi di Verona e di Mantova. -

'˜—Œ ˜ 'Ž ˜••˜ '— '˜ '•• ›Žœž'ÿž 'Ž Šœ›Š–Ž—

43,7&9:1&9.438=94=9-*=+4114<.3,=<-4=<.11=7*(*.;*=9-*= &(7&2*39=4+=&=43+.72&9.43=43=43)&>`=(94'*7=/`=,*,*a= Church of the Nativity at Immaculate Conception *;.=4-3=473*11= 1.;.&33*=43.(&= 4:8&<= 48*5-.3*= 1>25.&8=&?&7&8= 41.3=-.1.5=:11.;&3= Church of the Nativity at St. Leo’s & St. Patrick’s 3)7*<=-7.8945-*7=&7'*7= Church of the Nativity at &0-&1&=42.3.(=&991*= Saint Joseph’s 1*==&79.3=)*=477*8=*(0*7= .)&3=&7.&33*=45*=7.++.3= 22&= 4&3=4+= 7(=>2*= &.91>3= 4&3= .'1.3,= 47,&3= 4&3=4+= 7(=!4<3*8= 3)7*<= 3)7*<=479*7= "4'>3=1.?&'*9-=4+=:3,&7>=!7?*<.(0.= &9*1>3= 43&=4+=.8&=$&24:7*:== 3:= 3,*1&=(4+.*1)= %*77*3(*=!,3&9.:8=4+="4>41&=$>3,= .(-41&8=.(-41&8=0*;&1= *11*3=&97.(0=(&&81&3)= .(0= 4-3=9-*= 54891*=<&3= 89*11&= *73&7)=4+=*39-43='&3*;*7*3= *;.3=$7&3(.8=4+= 88.8.=(44)= # % % + ( %# # # ! " # # ( $ ! ( " $ ( ' % &% ! %# & ' %! ( , " - ( ! " # ( $ %# ) & * * ! " # , & , $ % ! " " # $ " $ % :3 & ' % & ' ! & -

Film Film Film Film

Annette Michelson’s contribution to art and film criticism over the last three decades has been un- paralleled. This volume honors Michelson’s unique C AMERA OBSCURA, CAMERA LUCIDA ALLEN AND TURVEY [EDS.] LUCIDA CAMERA OBSCURA, AMERA legacy with original essays by some of the many film FILM FILM scholars influenced by her work. Some continue her efforts to develop historical and theoretical frame- CULTURE CULTURE works for understanding modernist art, while others IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION practice her form of interdisciplinary scholarship in relation to avant-garde and modernist film. The intro- duction investigates and evaluates Michelson’s work itself. All in some way pay homage to her extraordi- nary contribution and demonstrate its continued cen- trality to the field of art and film criticism. Richard Allen is Associ- ate Professor of Cinema Studies at New York Uni- versity. Malcolm Turvey teaches Film History at Sarah Lawrence College. They recently collaborated in editing Wittgenstein, Theory and the Arts (Lon- don: Routledge, 2001). CAMERA OBSCURA CAMERA LUCIDA ISBN 90-5356-494-2 Essays in Honor of Annette Michelson EDITED BY RICHARD ALLEN 9 789053 564943 MALCOLM TURVEY Amsterdam University Press Amsterdam University Press WWW.AUP.NL Camera Obscura, Camera Lucida Camera Obscura, Camera Lucida: Essays in Honor of Annette Michelson Edited by Richard Allen and Malcolm Turvey Amsterdam University Press Front cover illustration: 2001: A Space Odyssey. Courtesy of Photofest Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: japes, Amsterdam isbn 90 5356 494 2 (paperback) nur 652 © Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 2003 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, me- chanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permis- sion of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. -

Medieval Music: Chant As Cure and Miracle Transcript

Medieval Music: Chant as Cure and Miracle Transcript Date: Thursday, 12 November 2015 - 1:00PM Location: St. Sepulchre Without Newgate 12 November 2015 Chant as Cure and Miracle Professor Christopher Page I begin with the life of a saint, a form of medieval writing that few read today outside the academy but which can nonetheless shed a great deal of light on many aspects of medieval life, thought and imagination. The one that concerns me here is a life of St. Bona of Pisa, written over seven hundred years ago. At one point, the author relates how some gifted singers, who are travelling together, enter a church and sing a chant for the purposes of offering their devotions but also no doubt for the pleasure of hearing their voices in a resonant space. According to the author I am following, they were so struck by the sound of their own voices fading into nothing in the vast spaces of the church – by the 'passing away' or transitus of their music – that they pondered the fading of all earthly things and decided to enter a monastery together. Perhaps they were thinking of the biblical text Wisdom 4,18: 'our time is as the flitting, the transitus, of a shadow'. There may indeed be something in the claim of the fifteenth-century composer and theorist, Adam of Fulda, that music is 'a philosophy, a true philosophy, a continuous meditation upon death'. It hath a dying fall. I imagine that most singers of the medieval Church, when they thought seriously about their task, accepted that theirs was the music of Mankind on the long march to Domesday: a trek that surely could not go on much longer as they looked back over their shoulders to the journey Humanity had made, since the time of our first parents, in the Garden of Eden. -

TWA EMPLOYEES See Page Four

King For A Day PUBLISHED BI-WEEKLY FOR TWA EMPLOYEES See Page Four VOL. NO. 25, NO. 7 MARCH 26, 1962 Two Top Posts TWA Places Order For Filled at MKC 10 Boeing 727 Jets KANSAS CITY—The appointment of John E. Harrington as system director of customer service effec NEW YORK—TWA is ordering 10 Boeing 727 jetliners, President tive April 1 has been announced by Charles C. Tillinghast, Jr., announced March 9. J. E. Frankum, vice president and At the same time, TWA revised an existing order for 20 Boeing general transportation manager. 707-131B and six 707-331B turofan jets. Under the revision, TWA General transportation manager will purchase 18 of the 131Bs and lease five of the larger, longer for the Central region since June, range 331Bs. The new contract also involves a lease-purchase 1959, Harrington succeeds J. I. agreement with Pratt & Whitney Aircraft for engines. Greenwald, who will transfer to The purchase order, including the airplanes, engines and spare the sales division. Greenwald's new duties will be announced later. parts involves approximately $174,000,000, President Tillinghast said. TWA's order for 20 Nouvelle Frankum also named Byron G. Jackson as director of terminal Caravelle jets from Sud Aviation of service. Formerly director of cus Brock Named France, announced last September, tomer service for the Central re has been revised so as to give gion, Jackson fills the position va TWA until May to determine cated recently by the transfer and To Sales Staff whether it wishes to proceed with promotion of Joseph A. -

The Lives of the Saints

'"Ill lljl ill! i j IIKI'IIIII '".'\;\\\ ','".. I i! li! millis i '"'''lllllllllllll II Hill P II j ill liiilH. CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Cornell University Library BR 1710.B25 1898 v.7 Lives of the saints. 3 1924 026 082 598 The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924026082598 *— * THE 3Utoe* of tt)e Saints; REV. S. BARING-GOULD SIXTEEN VOLUMES VOLUME THE SEVENTH *- -* . l£ . : |£ THE Itoes of tfje faints BY THE REV. S. BARING-GOULD, M.A. New Edition in 16 Volumes Revised with Introduction and Additional Lives of English Martyrs, Cornish and Welsh Saints, and a full Index to the Entire Work ILLUSTRATED BY OVER 400 ENGRAVINGS VOLUME THE SEVENTH KttljJ— PARTI LONDON JOHN C. NIMMO &° ' 1 NEW YORK : LONGMANS, GREEN, CO. MDCCCXCVIII *• — ;— * Printed by Ballantyne, Hanson & Co. At the Eallantyne Press *- -* CONTENTS' PAGE S. Athanasius, Deac. 127 SS. Aaron and Julius . I SS. AudaxandAnatholia 203 S. Adeodatus . .357 „ Agilulf . 211 SS. Alexanderandcomp. 207 S. Amalberga . , . 262 S. Bertha . 107 SS. AnatholiaandAudax 203 ,, Bonaventura 327 S. Anatolius,B. of Con- stantinople . 95 „ Anatolius, B.ofLao- dicea . 92 „ Andrew of Crete 106 S. Canute 264 Carileff. 12 „ Andrew of Rinn . 302 „ ... SS. Antiochus and SS. Castus and Secun- dinus Cyriac . 351 .... 3 Nicostra- S. Apollonius . 165 „ Claudius, SS. Apostles, The Sepa- tus, and others . 167 comp. ration of the . 347 „ Copres and 207 S. Cyndeus . 277 S. Apronia . .357 SS. Aquila and Pris- „ Cyril 205 Cyrus of Carthage . -

Jheronimus Bosch-His Sources

In the concluding review of his 1987 monograph on Jheronimus Bosch, Roger Marijnissen wrote: ‘In essays and studies on Bosch, too little attention has been paid to the people who Jheronimus Bosch: his Patrons and actually ordered paintings from him’. 1 And in L’ABCdaire de Jérôme Bosch , a French book published in 2001, the same author warned: ‘Ignoring the original destination and function his Public of a painting, one is bound to lose the right path. The function remains a basic element, and What we know and would like to know even the starting point of all research. In Bosch’s day, it was the main reason for a painting to exist’. 2 The third International Bosch Conference focuses precisely on this aspect, as we can read from the official announcement (’s-Hertogenbosch, September 2012): ‘New information Eric De Bruyn about the patrons of Bosch is of extraordinary importance, since such data will allow for a much better understanding of the original function of these paintings’. Gathering further information about the initial reception of Bosch’s works is indeed one of the urgent desiderata of Bosch research for the years to come. The objective of this introductory paper is to offer a state of affairs (up to September 2012) concerning the research on Bosch’s patronage and on the original function of his paintings. I will focus on those things that can be considered proven facts but I will also briefly mention what seem to be the most interesting hypotheses and signal a number of desiderata for future research. -

Musica Sanat Corpus Per Animam': Towar Tu Erstanding of the Use of Music

`Musica sanat corpus per animam': Towar tU erstanding of the Use of Music in Responseto Plague, 1350-1600 Christopher Brian Macklin Doctor of Philosophy University of York Department of Music Submitted March 2008 BEST COPY AVAILABLE Variable print quality 2 Abstract In recent decadesthe study of the relationship between the human species and other forms of life has ceased to be an exclusive concern of biologists and doctors and, as a result, has provided an increasingly valuable perspective on many aspectsof cultural and social history. Until now, however, these efforts have not extended to the field of music, and so the present study representsan initial attempt to understand the use of music in Werrn Europe's responseto epidemic plague from the beginning of the Black Death to the end of the sixteenth century. This involved an initial investigation of the description of sound in the earliest plague chronicles, and an identification of features of plague epidemics which had the potential to affect music-making (such as its geographical scope, recurrence of epidemics, and physical symptoms). The musical record from 1350-1600 was then examined for pieces which were conceivably written or performed during plague epidemics. While over sixty such pieces were found, only a small minority bore indications of specific liturgical use in time of plague. Rather, the majority of pieces (largely settings of the hymn Stella coeli extirpavit and of Italian laude whose diffusion was facilitated by the Franciscan order) hinted at a use of music in the everyday life of the laity which only occasionally resulted in the production of notated musical scores. -

Wisconsin Wind Siting Council

Dr. Mark Roberts Testimony, Ex. ____, Exhibit 4 Page 1 of 97 Wisconsin Wind Siting Council Wind Turbine Siting-Health Review and Wind Siting Policy Update October 2014 Dr. Mark Roberts Testimony, Ex. ____, Exhibit 4 Page 2 of 97 Dr. Mark Roberts Testimony, Ex. ____, Exhibit 4 Page 3 of 97 October 31, 2014 Chief Clerk Jeff Renk Wisconsin State Senate P.O. Box 7882 Madison, WI 53707 Chief Clerk Patrick E. Fuller Wisconsin State Assembly 17 West Main Street, Room 401 Madison, WI 53703 Re: Wind Turbine Siting-Health Review and Wind Siting Policy Update Pursuant to Wis. Stat. § 196.378(4g)(e). Dear Chief Renk and Chief Fuller: Enclosed for your review is the 2014 Report of the Wind Siting Council. This report is a summary of developments in the scientific literature regarding health effects associated with the operation of wind energy systems, and also includes state and national policy developments regarding wind siting policy. The Wind Siting Council has no recommendations to be considered for legislation at this time. On behalf of the Council, I wish to thank you for the opportunity to provide this report to the legislature. Sincerely, Carl W. Kuehne Wind Siting Council Chairperson Enclosure Dr. Mark Roberts Testimony, Ex. ____, Exhibit 4 Page 4 of 97 Dr. Mark Roberts Testimony, Ex. ____, Exhibit 4 Page 5 of 97 Contents Executive Summary 1 The Council at Work 5 Wind Siting Council Membership 5 Wind-health Report Drafting 5 Wind-policy Update Drafting 5 Council Review of Wind Turbine – Health Literature 6 Survey of Peer-reviewed Literature 6 Empirical Research 7 Reviews and Opinions 13 Conclusion 16 Wind Siting Policy Update 17 Findings Related to Wind Siting Rules under PSC 128 18 Jurisdiction 18 Noise 18 Turbine Setbacks 19 Shadow Flicker 20 Decommisioning 20 Signal Interference 20 Other Pertinent Findings 21 Permitting Process 21 Population Density 21 Property Impacts 22 Conclusion 22 Appendices Appendix A – Wind Siting Council Membership Appendix B – Peer Review Appendix C – Summary of Governmental Reports Dr. -

Alberto Aringhieri and the Chapel of Saint John the Baptist: Patronage, Politics, and the Cult of Relics in Renaissance Siena Timothy B

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2002 Alberto Aringhieri and the Chapel of Saint John the Baptist: Patronage, Politics, and the Cult of Relics in Renaissance Siena Timothy B. Smith Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF VISUAL ARTS AND DANCE ALBERTO ARINGHIERI AND THE CHAPEL OF SAINT JOHN THE BAPTIST: PATRONAGE, POLITICS, AND THE CULT OF RELICS IN RENAISSANCE SIENA By TIMOTHY BRYAN SMITH A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2002 Copyright © 2002 Timothy Bryan Smith All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Timothy Bryan Smith defended on November 1 2002. Jack Freiberg Professor Directing Dissertation Mark Pietralunga Outside Committee Member Nancy de Grummond Committee Member Robert Neuman Committee Member Approved: Paula Gerson, Chair, Department of Art History Sally McRorie, Dean, School of Visual Arts and Dance The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the abovenamed committee members. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First I must thank the faculty and staff of the Department of Art History, Florida State University, for unfailing support from my first day in the doctoral program. In particular, two departmental chairs, Patricia Rose and Paula Gerson, always came to my aid when needed and helped facilitate the completion of the degree. I am especially indebted to those who have served on the dissertation committee: Nancy de Grummond, Robert Neuman, and Mark Pietralunga. -

Renaissance at the Vatican

Mensile Data Novembre 2013 Sotheby’s Pagina 46-47 Foglio 1 / 3 ART WORLD INSIDER Renaissance at the vatican VI (reigned 1963 to 1978), who knew many artists from his time in Paris, inaugurated the collection of modern art in the Borgia Apartments, decorated in the 15th century by Pinturicchio and home to some 600 donated works of variable quality (ironically, the Vatican’s version of Bacon’s famous popes is not among the best). Now, the Vatican is once again engaging with work by living artists and this year, for the fi rst time, it has a national pavilion at the Venice Biennale with commissioned works by the Italian multimedia collective Studio Azzurro, the Czech photographer Josef Koudelka and the American painter Lawrence Carroll. What do you say to these who think the Church should sell all of its treasures and give it to the poor? If it sold all its masterpieces, the poor would be poorer. Everything that is here is for the people of the world. Has the election of Pope Francis made a difference? PROFESSOR ANTONIO PAOLUCCI, DIRECTOR, VATICAN MUSEUMS Because of him, even more people have come to Rome. After the Angelus prayer and the papal audiences, they want to see the museums. We have 5.1 Anna Somers Cocks profi les Professor Antonio million visitors a year and I would like to have zero Paolucci, the custodian of one of the world’s growth now. greatest repositories of art at the Vatican Museums in Rome What is the role of the Vatican Museums? People expect them to be very pious: instead, you see After a brilliant career as a museum director in more male and female nudes than in most museums.