Interspecific Variation in the Bony Labyrinth (Inner Ear) of Anurans. Amber L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pulsed Evolution Shaped Modern Vertebrate Body Sizes

Pulsed evolution shaped modern vertebrate body sizes Michael J. Landisa and Joshua G. Schraiberb,c,1 aDepartment of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06520; bDepartment of Biology, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA 19122; and cInstitute for Genomics and Evolutionary Medicine, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA 19122 Edited by Neil H. Shubin, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, and approved October 6, 2017 (received for review June 18, 2017) The relative importance of different modes of evolution in shap- ties of these methods, nor is much known about the prevalence of ing phenotypic diversity remains a hotly debated question. Fos- pulsed change throughout some of Earth’s most intensely stud- sil data suggest that stasis may be a common mode of evolution, ied clades. while modern data suggest some lineages experience very fast Here, we examine evidence for pulsed evolution across ver- rates of evolution. One way to reconcile these observations is to tebrate taxa, using a method for fitting L´evy processes to com- imagine that evolution proceeds in pulses, rather than in incre- parative data. These processes can capture both incremental and ments, on geological timescales. To test this hypothesis, we devel- pulsed modes of evolution in a single, simple framework. We oped a maximum-likelihood framework for fitting Levy´ processes apply this method to analyze 66 vertebrate clades containing to comparative morphological data. This class of stochastic pro- 8,323 extant species for evidence of pulsed evolution by compar- cesses includes both an incremental and a pulsed component. We ing the statistical fit of several varieties of L´evy jump processes found that a plurality of modern vertebrate clades examined are (modeling different types of pulsed evolution) to three models best fitted by pulsed processes over models of incremental change, that emphasize alternative macroevolutionary dynamics. -

Fallen in a Dead Ear: Intralabyrinthine Preservation of Stapes in Fossil Artiodactyls Maeva Orliac, Guillaume Billet

Fallen in a dead ear: intralabyrinthine preservation of stapes in fossil artiodactyls Maeva Orliac, Guillaume Billet To cite this version: Maeva Orliac, Guillaume Billet. Fallen in a dead ear: intralabyrinthine preservation of stapes in fossil artiodactyls. Palaeovertebrata, 2016, 40 (1), 10.18563/pv.40.1.e3. hal-01897786 HAL Id: hal-01897786 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01897786 Submitted on 17 Oct 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/297725060 Fallen in a dead ear: intralabyrinthine preservation of stapes in fossil artiodactyls Article · March 2016 DOI: 10.18563/pv.40.1.e3 CITATIONS READS 2 254 2 authors: Maeva Orliac Guillaume Billet Université de Montpellier Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle 76 PUBLICATIONS 745 CITATIONS 103 PUBLICATIONS 862 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: The ear region of Artiodactyla View project Origin, evolution, and dynamics of Amazonian-Andean ecosystems View project All content following this page was uploaded by Maeva Orliac on 14 March 2016. -

CONGENITAL MALFORMATIONS of the INNER EAR Malformaciones Congénitas Del Oído Interno

topic review CONGENITAL MALFORMATIONS OF THE INNER EAR Malformaciones congénitas del oído interno. Revisión de tema Laura Vanessa Ramírez Pedroza1 Hernán Darío Cano Riaño2 Federico Guillermo Lubinus Badillo2 Summary Key words (MeSH) There are a great variety of congenital malformations that can affect the inner ear, Ear with a diversity of physiopathologies, involved altered structures and age of symptom Ear, inner onset. Therefore, it is important to know and identify these alterations opportunely Hearing loss Vestibule, labyrinth to lower the risks of all the complications, being of great importance, among others, Cochlea the alterations in language development and social interactions. Magnetic resonance imaging Resumen Existe una gran variedad de malformaciones congénitas que pueden afectar al Palabras clave (DeCS) oído interno, con distintas fisiopatologías, diferentes estructuras alteradas y edad Oído de aparición de los síntomas. Por lo anterior, es necesario conocer e identificar Oído interno dichas alteraciones, con el fin de actuar oportunamente y reducir el riesgo de las Pérdida auditiva Vestíbulo del laberinto complicaciones, entre otras —de gran importancia— las alteraciones en el área del Cóclea lenguaje y en el ámbito social. Imagen por resonancia magnética 1. Epidemiology • Hyperbilirubinemia Ear malformations occur in 1 in 10,000 or 20,000 • Respiratory distress from meconium aspiration cases (1). One in every 1,000 children has some degree • Craniofacial alterations (3) of sensorineural hearing impairment, with an average • Mechanical ventilation for more than five days age at diagnosis of 4.9 years. The prevalence of hearing • TORCH Syndrome (4) impairment in newborns with risk factors has been determined to be 9.52% (2). -

ANATOMY of EAR Basic Ear Anatomy

ANATOMY OF EAR Basic Ear Anatomy • Expected outcomes • To understand the hearing mechanism • To be able to identify the structures of the ear Development of Ear 1. Pinna develops from 1st & 2nd Branchial arch (Hillocks of His). Starts at 6 Weeks & is complete by 20 weeks. 2. E.A.M. develops from dorsal end of 1st branchial arch starting at 6-8 weeks and is complete by 28 weeks. 3. Middle Ear development —Malleus & Incus develop between 6-8 weeks from 1st & 2nd branchial arch. Branchial arches & Development of Ear Dev. contd---- • T.M at 28 weeks from all 3 germinal layers . • Foot plate of stapes develops from otic capsule b/w 6- 8 weeks. • Inner ear develops from otic capsule starting at 5 weeks & is complete by 25 weeks. • Development of external/middle/inner ear is independent of each other. Development of ear External Ear • It consists of - Pinna and External auditory meatus. Pinna • It is made up of fibro elastic cartilage covered by skin and connected to the surrounding parts by ligaments and muscles. • Various landmarks on the pinna are helix, antihelix, lobule, tragus, concha, scaphoid fossa and triangular fossa • Pinna has two surfaces i.e. medial or cranial surface and a lateral surface . • Cymba concha lies between crus helix and crus antihelix. It is an important landmark for mastoid antrum. Anatomy of external ear • Landmarks of pinna Anatomy of external ear • Bat-Ear is the most common congenital anomaly of pinna in which antihelix has not developed and excessive conchal cartilage is present. • Corrections of Pinna defects are done at 6 years of age. -

Phylogenetic Analyses Reveal Unexpected Patterns in the Evolution of Reproductive Modes in Frogs

ORIGINAL ARTICLE doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2012.01715.x PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSES REVEAL UNEXPECTED PATTERNS IN THE EVOLUTION OF REPRODUCTIVE MODES IN FROGS Ivan Gomez-Mestre,1,2 Robert Alexander Pyron,3 and John J. Wiens4 1Estacion´ Biologica´ de Donana,˜ Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientıficas,´ Avda. Americo Vespucio s/n, Sevilla 41092, Spain 2E-mail: [email protected] 3Department of Biological Sciences, The George Washington University, Washington DC 20052 4Department of Ecology and Evolution, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, New York 11794–5245 Received November 2, 2011 Accepted June 2, 2012 Understanding phenotypic diversity requires not only identification of selective factors that favor origins of derived states, but also factors that favor retention of primitive states. Anurans (frogs and toads) exhibit a remarkable diversity of reproductive modes that is unique among terrestrial vertebrates. Here, we analyze the evolution of these modes, using comparative methods on a phylogeny and matched life-history database of 720 species, including most families and modes. As expected, modes with terrestrial eggs and aquatic larvae often precede direct development (terrestrial egg, no tadpole stage), but surprisingly, direct development evolves directly from aquatic breeding nearly as often. Modes with primitive exotrophic larvae (feeding outside the egg) frequently give rise to direct developers, whereas those with nonfeeding larvae (endotrophic) do not. Similarly, modes with eggs and larvae placed in locations protected from aquatic predators evolve frequently but rarely give rise to direct developers. Thus, frogs frequently bypass many seemingly intermediate stages in the evolution of direct development. We also find significant associations between terrestrial reproduction and reduced clutch size, larger egg size, reduced adult size, parental care, and occurrence in wetter and warmer regions. -

An Overdue Review and Reclassification of the Australasian

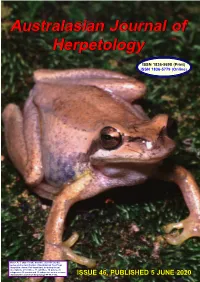

AustralasianAustralasian JournalJournal ofof HerpetologyHerpetology ISSN 1836-5698 (Print) ISSN 1836-5779 (Online) Hoser, R. T. 2020. For the first time ever! An overdue review and reclassification of Australasian Tree Frogs (Amphibia: Anura: Pelodryadidae), including formal descriptions of 12 tribes, 11 subtribes, 34 genera, 26 subgenera, 62 species and 12 subspecies new to science. Australasian Journal of Herpetology 44-46:1-192. ISSUE 46, PUBLISHED 5 JUNE 2020 Hoser, R. T. 2020. For the first time ever! An overdue review and reclassification of Australasian Tree Frogs (Amphibia: Anura: Pelodryadidae), including formal descriptions of 12 tribes, 11 subtribes, 34 genera, 26 130 Australasiansubgenera, 62 species Journal and 12 subspecies of Herpetologynew to science. Australasian Journal of Herpetology 44-46:1-192. ... Continued from AJH Issue 45 ... zone of apparently unsuitable habitat of significant geological antiquity and are therefore reproductively Underside of thighs have irregular darker patches and isolated and therefore evolving in separate directions. hind isde of thigh has irregular fine creamish coloured They are also morphologically divergent, warranting stripes. Skin is leathery and with numerous scattered identification of the unnamed population at least to tubercles which may or not be arranged in well-defined subspecies level as done herein. longitudinal rows, including sometimes some of medium to large size and a prominent one on the eyelid. Belly is The zone dividing known populations of each species is smooth except for some granular skin on the lower belly only about 30 km in a straight line. and thighs. Vomerine teeth present, but weakly P. longirostris tozerensis subsp. nov. is separated from P. -

Antipredator Mechanisms of Post-Metamorphic Anurans: a Global Database and Classification System

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU Ecology Center Publications Ecology Center 5-1-2019 Antipredator Mechanisms of Post-Metamorphic Anurans: A Global Database and Classification System Rodrigo B. Ferreira Utah State University Ricardo Lourenço-de-Moraes Universidade Estadual de Maringá Cássio Zocca Universidade Vila Velha Charles Duca Universidade Vila Velha Karen H. Beard Utah State University Edmund D. Brodie Jr. Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/eco_pubs Part of the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Recommended Citation Ferreira, R.B., Lourenço-de-Moraes, R., Zocca, C. et al. Behav Ecol Sociobiol (2019) 73: 69. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s00265-019-2680-1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Ecology Center at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ecology Center Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Antipredator mechanisms of post-metamorphic anurans: a global database and 2 classification system 3 4 Rodrigo B. Ferreira1,2*, Ricardo Lourenço-de-Moraes3, Cássio Zocca1, Charles Duca1, Karen H. 5 Beard2, Edmund D. Brodie Jr.4 6 7 1 Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ecologia de Ecossistemas, Universidade Vila Velha, Vila Velha, ES, 8 Brazil 9 2 Department of Wildland Resources and the Ecology Center, Utah State University, Logan, UT, United 10 States of America 11 3 Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ecologia de Ambientes Aquáticos Continentais, Universidade Estadual 12 de Maringá, Maringá, PR, Brazil 13 4 Department of Biology and the Ecology Center, Utah State University, Logan, UT, United States of 14 America 15 16 *Corresponding author: Rodrigo B. -

The Temporal Bone

Anatomic Moment The Temporal Bone Joel D. Swartz, David L. Daniels, H. Ric Harnsberger, Katherine A. Shaffer, and Leighton Mark Despite the advent of thin-section high-reso- the inner ear structures and the external lution computed tomography and, more re- environment. cently, unique magnetic resonance imaging se- Virtually all textbooks define the inner ear as quences with thin sections, T2 weighting, and a membranous labyrinth housed within an os- maximum-intensity projection techniques, seous labyrinth. The membranous labyrinth three-dimensional neuroanatomy of the tempo- contains endolymph, a fluid rich in potassium ral bone and related structures remains some- and low in sodium, similar to intracellular fluid. what of an enigma to many medical specialists, Interposed between the membranous labyrinth neuroradiologists included. Therefore, we are and the osseous labyrinth resides a supportive undertaking a series of anatomic moments in perilymphatic labyrinth. Perilymph is similar to the hope of solidifying the most important ana- cerebrospinal fluid and other extracellular tissue tomic concepts as they relate to this region. Our fluid. approach will be organized so as to consider the The osseous labyrinth consists of the bony temporal bone to represent the complex inter- edifice for the vestibule, semicircular canals, relationship of three systems: hearing, balance, cochlea, and vestibular aqueduct. The mem- and related neuroanatomic and neurovascular branous labyrinth consists of the utricle and structures. saccule (located within the vestibule), the semi- The ear originated in fish as a water motion circular ducts, the cochlear duct, and the en- detection system (1). The vestibular (balance) dolymphatic duct. The latter is a channel within mechanism becomes more complex as we the vestibular aqueduct with communications to scale the embryologic ladder and endolymph the utricle and saccule. -

Rampant Tooth Loss Across 200 Million Years of Frog Evolution

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.04.429809; this version posted February 6, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. 1 Rampant tooth loss across 200 million years of frog evolution 2 3 4 Daniel J. Paluh1,2, Karina Riddell1, Catherine M. Early1,3, Maggie M. Hantak1, Gregory F.M. 5 Jongsma1,2, Rachel M. Keeffe1,2, Fernanda Magalhães Silva1,4, Stuart V. Nielsen1, María Camila 6 Vallejo-Pareja1,2, Edward L. Stanley1, David C. Blackburn1 7 8 1Department of Natural History, Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida, 9 Gainesville, Florida USA 32611 10 2Department of Biology, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida USA 32611 11 3Biology Department, Science Museum of Minnesota, Saint Paul, Minnesota USA 55102 12 4Programa de Pós Graduação em Zoologia, Universidade Federal do Pará/Museu Paraense 13 Emilio Goeldi, Belém, Pará Brazil 14 15 *Corresponding author: Daniel J. Paluh, [email protected], +1 814-602-3764 16 17 Key words: Anura; teeth; edentulism; toothlessness; trait lability; comparative methods 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.04.429809; this version posted February 6, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. -

3Systematics and Diversity of Extant Amphibians

Systematics and Diversity of 3 Extant Amphibians he three extant lissamphibian lineages (hereafter amples of classic systematics papers. We present widely referred to by the more common term amphibians) used common names of groups in addition to scientifi c Tare descendants of a common ancestor that lived names, noting also that herpetologists colloquially refer during (or soon after) the Late Carboniferous. Since the to most clades by their scientifi c name (e.g., ranids, am- three lineages diverged, each has evolved unique fea- bystomatids, typhlonectids). tures that defi ne the group; however, salamanders, frogs, A total of 7,303 species of amphibians are recognized and caecelians also share many traits that are evidence and new species—primarily tropical frogs and salaman- of their common ancestry. Two of the most defi nitive of ders—continue to be described. Frogs are far more di- these traits are: verse than salamanders and caecelians combined; more than 6,400 (~88%) of extant amphibian species are frogs, 1. Nearly all amphibians have complex life histories. almost 25% of which have been described in the past Most species undergo metamorphosis from an 15 years. Salamanders comprise more than 660 species, aquatic larva to a terrestrial adult, and even spe- and there are 200 species of caecilians. Amphibian diver- cies that lay terrestrial eggs require moist nest sity is not evenly distributed within families. For example, sites to prevent desiccation. Thus, regardless of more than 65% of extant salamanders are in the family the habitat of the adult, all species of amphibians Plethodontidae, and more than 50% of all frogs are in just are fundamentally tied to water. -

B005DTJC8Y.Usermanual.Pdf

V2010 Auris Latin Auris externa 1 Auricula 2 Meatus acusticus externus 3 Membrana tympanica Auris media 4 Ossicula auditus: 4 a Malleus 4 b Incus 4 c Stapes 5 Cavitas tympani 6 Tuba auditiva 7 Fenestra vestibuli 8 Fenestra cochleae Auris interna 9 Labyrinthus osseus: 9 a Canalis semicircularis posterior 9 b Canalis semicircularis lateralis 9 c Canalis semicircularis anterior 9 d Vestibulum 9 e Cochlea 10 N. vestibularis 11 N. cochlearis ® 12 N. vestibulocochlearis [VIII] 13 Lig. spirale 14 Scala vestibuli 15 Ductus cochlearis 16 Scala tympani 17 N. cochlearis 18 Ganglion cochleare 19 Organum spirale 20 Modiolus cochleae 21 Paries vestibularis 22 Sulcus spiralis internus 23 Membrana tectoria 24 Cuniculus medius 25 Cuniculus externus 26 Cellulae terminales externae 27 Cellulae sustentaculares externae 28 Sulcus spiralis externus 29 Lamina basilaris 30 Cellulae phalangea externae 31 Cellulae capillares externae 32 Cellula stela externa 33 Cuniculus internus 34 Cellula capillaris interna 35 Cellula stela interna 36 Lamina spiralis ossea 37 Limbus spiralis English The Ear A Sectional view of the human ear B Sectional view of cochlea C Sectional view of cochlear duct with spiral organ External ear 1 Auricle 2 External acoustic meatus 3 Tympanic membrane Middle ear 4 Auditory ossicles: 4 a Malleus 4 b Incus 4 c Stapes 5 Tympanic cavity 6 Pharyngotympanice tube 7 Oval window 8 Round window Internal ear 9 Bony labyrinth 9 a Posterior semicircular canal 9 b Lateral semicircular canal 9 c Anterior semicircular canal ® 9 d Vestibule 9 e Cochlea 10 -

BOA5.1-2 Frog Biology, Taxonomy and Biodiversity

The Biology of Amphibians Agnes Scott College Mark Mandica Executive Director The Amphibian Foundation [email protected] 678 379 TOAD (8623) Phyllomedusidae: Agalychnis annae 5.1-2: Frog Biology, Taxonomy & Biodiversity Part 2, Neobatrachia Hylidae: Dendropsophus ebraccatus CLassification of Order: Anura † Triadobatrachus Ascaphidae Leiopelmatidae Bombinatoridae Alytidae (Discoglossidae) Pipidae Rhynophrynidae Scaphiopopidae Pelodytidae Megophryidae Pelobatidae Heleophrynidae Nasikabatrachidae Sooglossidae Calyptocephalellidae Myobatrachidae Alsodidae Batrachylidae Bufonidae Ceratophryidae Cycloramphidae Hemiphractidae Hylodidae Leptodactylidae Odontophrynidae Rhinodermatidae Telmatobiidae Allophrynidae Centrolenidae Hylidae Dendrobatidae Brachycephalidae Ceuthomantidae Craugastoridae Eleutherodactylidae Strabomantidae Arthroleptidae Hyperoliidae Breviceptidae Hemisotidae Microhylidae Ceratobatrachidae Conrauidae Micrixalidae Nyctibatrachidae Petropedetidae Phrynobatrachidae Ptychadenidae Ranidae Ranixalidae Dicroglossidae Pyxicephalidae Rhacophoridae Mantellidae A B † 3 † † † Actinopterygian Coelacanth, Tetrapodomorpha †Amniota *Gerobatrachus (Ray-fin Fishes) Lungfish (stem-tetrapods) (Reptiles, Mammals)Lepospondyls † (’frogomander’) Eocaecilia GymnophionaKaraurus Caudata Triadobatrachus 2 Anura Sub Orders Super Families (including Apoda Urodela Prosalirus †) 1 Archaeobatrachia A Hyloidea 2 Mesobatrachia B Ranoidea 1 Anura Salientia 3 Neobatrachia Batrachia Lissamphibia *Gerobatrachus may be the sister taxon Salientia Temnospondyls