CAC-Editorial-1.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

China Data Supplement March 2008 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC ......................................................................... 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC ..................................................................... 31 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership ...................................................................... 38 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries ......................................................................... 54 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations .............................................................................................. 56 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR ................................................................................................................ 58 LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR ....................................................................................................................... 65 LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan .............................................................................................................................. 69 LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 March 2008 The Main National Leadership of the -

Transnational Mathematics and Movements: Shiing- Shen Chern, Hua Luogeng, and the Princeton Institute for Advanced Study from World War II to the Cold War1

Chinese Annals of History of Science and Technology 3 (2), 118–165 (2019) doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1461.2019.02118 Transnational Mathematics and Movements: Shiing- shen Chern, Hua Luogeng, and the Princeton Institute for Advanced Study from World War II to the Cold War1 Zuoyue Wang 王作跃,2 Guo Jinhai 郭金海3 (California State Polytechnic University, Pomona 91768, US; Institute for the History of Natural Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100190, China) Abstract: This paper reconstructs, based on American and Chinese primary sources, the visits of Chinese mathematicians Shiing-shen Chern 陈省身 (Chen Xingshen) and Hua Luogeng 华罗庚 (Loo-Keng Hua)4 to the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton in the United States in the 1940s, especially their interactions with Oswald Veblen and Hermann Weyl, two leading mathematicians at the IAS. It argues that Chern’s and Hua’s motivations and choices in regard to their transnational movements between China and the US were more nuanced and multifaceted than what is presented in existing accounts, and that socio-political factors combined with professional-personal ones to shape their decisions. The paper further uses their experiences to demonstrate the importance of transnational scientific interactions for the development of science in China, the US, and elsewhere in the twentieth century. Keywords: Shiing-shen Chern, Chen Xingshen, Hua Luogeng, Loo-Keng Hua, Institute for 1 This article was copy-edited by Charlie Zaharoff. 2 Research interests: History of science and technology in the United States, China, and transnational contexts in the twentieth century. He is currently writing a book on the history of American-educated Chinese scientists and China-US scientific relations. -

Britain in the 2020S

REPORT FUTURE PROOF BRITAIN IN THE 2020S Mathew Lawrence December 2016 © IPPR 2016 Institute for Public Policy Research INTRODUCTION Brexit is the firing gun on a decade of disruption. As the UK negotiates its new place in the world, an accelerating wave of economic, social and technological change will reshape the country, in often quite radical ways. In this report, we set out five powerful trends that will drive change in the 2020s. 1. A demographic tipping point: As the population grows, the UK is set to age sharply and become increasingly diverse. Globally, the long expansion of the working-age CONTENTS population is set to slow sharply. 2. An economic world transformed: The economic world order will become more Introduction ............................................................................................................ 3 fragile as globalisation evolves, trade patterns shift, and economic power gravitates toward Asia. At the same time, developed economies are likely to struggle to escape Executive summary: The UK in 2030 ..................................................................... 4 conditions of secular stagnation. The institutions governing the global economy are A world transformed: Five major disruptive forces reshaping Britain .................. 6 likely to come under intense pressure as the American hegemony that underpinned the postwar international order fades and the Global South rises in economic and Britain at the periphery? ..................................................................................8 -

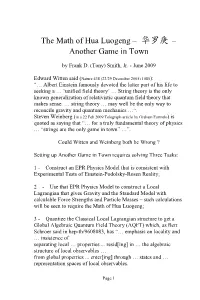

The Math of Hua Luogeng – 华罗庚 - Another Game in Town

The Math of Hua Luogeng – 华罗庚 - Another Game in Town by Frank D. (Tony) Smith, Jr. - June 2009 Edward Witten said (Nature 438 (22/29 December 2005) 1085): “… Albert Einstein famously devoted the latter part of his life to seeking a … ‘unified field theory’ … String theory is the only known generalization of relativistic quantum field theory that makes sense. … string theory … may well be the only way to reconcile gravity and quantum mechanics …“. Steven Weinberg (in a 22 Feb 2009 Telegraph article by Graham Farmelo) is quoted as saying that “… for a truly fundamental theory of physics … “strings are the only game in town” …”. Could Witten and Weinberg both be Wrong ? Setting up Another Game in Town requires solving Three Tasks: 1 - Construct an EPR Physics Model that is consistent with Experimental Tests of Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen Reality; 2 - Use that EPR Physics Model to construct a Local Lagrangian that gives Gravity and the Standard Model with calculable Force Strengths and Particle Masses – such calculations will be seen to require the Math of Hua Luogeng; 3 - Quantize the Classical Local Lagrangian structure to get a Global Algebraic Quantum Field Theory (AQFT) which, as Bert Schroer said in hep-th/9608083, has “… emphasis on locality and … insistence of separating local … properties ... resid[ing] in … the algebraic structure of local observables … from global properties ... enter[ing] through … states and … representation spaces of local observables. Page 1 1 - An EPR Physics Model Joy Christian in arXiv 0904.4259 “Disproofs of Bell, GHZ, and Hardy Type Theorems and the Illusion of Entanglement” says: “… a [geometrically] correct local-realistic framework … provides exact, deterministic, and local underpinnings for at least the Bell, GHZ-3, GHZ-4, and Hardy states. -

Should System Dynamics Be Described As a `Hard' Or `Deterministic' Systems Approach?

Systems Research and Behavioral Science Syst. Res. 17, 3–22 (2000) & Research Paper Should System Dynamics be Described as a `Hard' or `Deterministic' Systems Approach? David C. Lane* Operational Research Department, London School of Economics and Political Science, University of London, London, UK This paper explores the criticism that system dynamics is a `hard' or `deterministic' systems approach. This criticism is seen to have four interpretations and each is addressed from the perspectives of social theory and systems science. Firstly, system dynamics is shown to offer not prophecies but Popperian predictions. Secondly, it is shown to involve the view that system structure only partially, not fully, determines human behaviour. Thirdly, the field's assumptions are shown not to constitute a grand content theory Ð though its structural theory and its attachment to the notion of causality in social systems are acknowledged. Finally, system dynamics is shown to be significantly different from systems engineering. The paper concludes that such confusions have arisen partially because of limited communication at the theoretical level from within the system dynamics community but also because of imperfect command of the available literature on the part of external commentators. Improved communication on theoretical issues is encouraged, though it is observed that system dynamics will continue to justify its assumptions primarily from the point of view of practical problem solving. The answer to the question in the paper's title is therefore: on balance, no. Copyright # 2000 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Keywords systems theory; systems thinking; information feedback; systems engineering; social theory; philosophy INTRODUCTION approach is then introduced. -

China Nuclear Chronology

China Nuclear Chronology 2011-2010 | 2009-2008 | 2007-2005 | 2004-2002 | 2001 | 2000-1999 | 1998-1997 | 1996-1995 1994-1992 | 1991-1990 | 1989-1985 | 1984-1980 | 1979-1970 | 1969-1960 | 1959-1945 Last update: July 2011 2011-2010 14 June 2011 China completes nuclear inspections of all 13 currently operating power reactors. According to Li Ganjie, Vice- Minister of the Ministry of Environmental Protection, safety evaluations of the 28 reactors under construction should be completed by October. Six weeks earlier, China declared its military nuclear facilities safe. Li emphasizes that the lessons from "Japan's Fukushima nuclear crisis are profound," and that China is working on a comprehensive and effective nuclear safety plan. Li confirms that China still plans to construct more than 100 reactors by 2020. On the other hand, "[China] needs to control the pace of [the nuclear energy] development," according to Zheng Yuhui, director of the research center of the China Nuclear Energy Association. The Chinese Academy of Sciences scholars add that China should maintain a relatively stable policy for nuclear power development and further strengthen nuclear safety. —中华人民共和国中央人民政府 [The Central People's Government of the People's Republic of China], "环境保护部副部长会见美国能源部核能助理部长 [Vice-Minister of the Ministry of Environmental Protection Met the United States Department of Energy's Assistant Secretary for Nuclear Energy]," 14 June 2011, www.gov.cn; "After Inspections, China Moves Ahead with Nuclear Plans," The New York Times, 17 June 2011; "China Suspends New Nuclear Plant Approvals," China Daily (Edition in English), 15 June 2011, www.chinadialy.com; "China May Resume Giving Approvals to New Nuclear Plants-Official," BBC Monitoring Asia Pacific, 25 June 2011; "Experts: China Should Keep Nuclear Power Policy Stable," People's Daily (Edition in English), 25 May 2011; "Chinese Military Nuke Facilities Declared Safe," Global Security Newswire, 1 April 2011, www.gsn.nti.org. -

ZHENG Zhemin Honored with State Supreme S&T Award CAS

Vol.27 No.2 2013 InBrief ZHENG Zhemin Honored with State Supreme S&T Award For his pioneering and lasting contributions to explosive mechanics in China, Prof. ZHENG Zhemin from the Institute InBrief of Mechanics, Chinese Academy of Sciences received the State Supreme S&T Award, which is the highest honor for science workers in China, from President HU Jintao on January 18, 2013 at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing. Prof. ZHENG has been engaged in the study of explosive mechanics for over six decades. Born in 1924 in Shandong Province as the son of a successful businessman, ZHENG suffered from the Second World War and was determined to do something for his nation as a boy. During his senior year at Tsinghua University, he was inspired by his teacher QIAN Weichang, China’s late “father of mechanics” and became very interested in mechanics. In 1952 he earned his PhD from the California Institute of Technology under the supervision of Prof. QIAN Xuesen, who later became ZHENG (R) receives the award from Chinese President HU Jintao (L). the founding father of China’s space and missile programs. ZHENG returned to China in 1955, joined the Chinese Mechanics and founding director of the State Key Laboratory Academy of Sciences and soon started his investigations into for Nonlinear Mechanics. He is a laureate of the Tan Kah Kee the mechanism of explosions. He proposed the basic theories Science Award in 1993. and technologies for explosive modeling, and his research “I didn’t expect such a supreme award. I’m very was applied to the manufacturing of key components of the delighted. -

(Hrsg.) Strafrecht in Reaktion Auf Systemunrecht

Albin Eser / Ulrich Sieber / Jörg Arnold (Hrsg.) Strafrecht in Reaktion auf Systemunrecht Schriftenreihe des Max-Planck-Instituts für ausländisches und internationales Strafrecht Strafrechtliche Forschungsberichte Herausgegeben von Ulrich Sieber in Fortführung der Reihe „Beiträge und Materialien aus dem Max-Planck-Institut für ausländisches und internationales Strafrecht Freiburg“ begründet von Albin Eser Band S 82.9 Strafrecht in Reaktion auf Systemunrecht Vergleichende Einblicke in Transitionsprozesse herausgegeben von Albin Eser • Ulrich Sieber • Jörg Arnold Band 9 China von Thomas Richter sdfghjk Duncker & Humblot • Berlin Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über <http://dnb.ddb.de> abrufbar. DOI https://doi.org/10.30709/978-3-86113-876-X Redaktion: Petra Lehser Alle Rechte vorbehalten © 2006 Max-Planck-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften e.V. c/o Max-Planck-Institut für ausländisches und internationales Strafrecht Günterstalstraße 73, 79100 Freiburg i.Br. http://www.mpicc.de Vertrieb in Gemeinschaft mit Duncker & Humblot GmbH, Berlin http://WWw.duncker-humblot.de Umschlagbild: Thomas Gade, © www.medienarchiv.com Druck: Stückle Druck und Verlag, Stückle-Straße 1, 77955 Ettenheim Printed in Germany ISSN 1860-0093 ISBN 3-86113-876-X (Max-Planck-Institut) ISBN 3-428-12129-5 (Duncker & Humblot) Gedruckt auf alterungsbeständigem (säurefreiem) Papier entsprechend ISO 9706 # Vorwort der Herausgeber Mit dem neunten Band der Reihe „Strafrecht in Reaktion auf Systemunrecht – Vergleichende Einblicke in Transitionsprozesse“ wird zur Volksrepublik China ein weiterer Landesbericht vorgelegt. Während die bisher erschienenen Bände solche Länder in den Blick nahmen, die hinsichtlich der untersuchten Transitionen einem „klassischen“ Systemwechsel von der Diktatur zur Demokratie entsprachen, ist die Einordung der Volksrepublik China schwieriger. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

China Data Supplement March 2007 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 45 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 48 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 51 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 58 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 62 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 March 2007 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member BoD Board of Directors Cdr. Commander CEO Chief Executive Officer Chp. Chairperson COO Chief Operating Officer CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep.Cdr. Deputy Commander Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson Hon.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

What Is Systems Theory?

What is Systems Theory? Systems theory is an interdisciplinary theory about the nature of complex systems in nature, society, and science, and is a framework by which one can investigate and/or describe any group of objects that work together to produce some result. This could be a single organism, any organization or society, or any electro-mechanical or informational artifact. As a technical and general academic area of study it predominantly refers to the science of systems that resulted from Bertalanffy's General System Theory (GST), among others, in initiating what became a project of systems research and practice. Systems theoretical approaches were later appropriated in other fields, such as in the structural functionalist sociology of Talcott Parsons and Niklas Luhmann . Contents - 1 Overview - 2 History - 3 Developments in system theories - 3.1 General systems research and systems inquiry - 3.2 Cybernetics - 3.3 Complex adaptive systems - 4 Applications of system theories - 4.1 Living systems theory - 4.2 Organizational theory - 4.3 Software and computing - 4.4 Sociology and Sociocybernetics - 4.5 System dynamics - 4.6 Systems engineering - 4.7 Systems psychology - 5 See also - 6 References - 7 Further reading - 8 External links - 9 Organisations // Overview 1 / 20 What is Systems Theory? Margaret Mead was an influential figure in systems theory. Contemporary ideas from systems theory have grown with diversified areas, exemplified by the work of Béla H. Bánáthy, ecological systems with Howard T. Odum, Eugene Odum and Fritj of Capra , organizational theory and management with individuals such as Peter Senge , interdisciplinary study with areas like Human Resource Development from the work of Richard A. -

Simple Rules for a Complex World with Artificial Intelligence

Simple Rules for a Complex World with Artificial Intelligence Jes´usFern´andez-Villaverde1 April 28, 2020 1University of Pennsylvania A complex world with AI and ML • It is hard to open the internet or browse a bookstore without finding an article or a book discussing artificial intelligence (AI) and, in particular, machine learning (ML). • I will define some of these concepts more carefully later on. • Many concerns: effects of AI and ML on jobs, wealth and income inequality, ... • Some observers even claim that gone is the era of large armies and powerful navies. The nations with the best algorithms, as the Roman said in the Aeneid, \will rule mankind, and make the world obey." 1 2 AI, ML, and public policy, I • One thread that increasingly appears in these works, and which is bound to become a prominent concern, is how AI can address policy questions. • Some proposals are mild. • For example, thanks to ML: 1. We might be able to detect early strains in the financial markets and allow regulatory agencies to respond before damage occurs. 2. We might be able to fight electronic fraud and money laundering. 3. We might be able to improve public health. • I do not have any problem with these applications. Natural extension of models used in econometrics for decades. 3 AI, ML, and public policy, II • Some proposals are radical: \digital socialism" (Saros, 2014, Phillips and Rozworski, 2019, and Morozov, 2019). • The defenders of this view argue that some form of AI or ML can finally achieve the promise of central planning: we will feed a computer (or a system of computers) all the relevant information and, thanks to ML (the details are often fuzzy), we will get an optimal allocation of goods and income. -

Error Correction. Chilean Cybernetics and Chicago's Economists

[2] Error Correction: Chilean Cybernetics and Chicago’s Economists Adrian Lahoud Cybernetics is a specific way of conceiving the relation between information and government: It represented a way of bringing the epistemological and the onto- logical together in real time. The essay explores a par- adigmatic case study in the evolution of this history: the audacious experiment in cybernetic management known as Project Cybersyn that was developed follow- ing Salvador Allende’s ascension to power in Chile in 1970. In ideological terms, Allende’s socialism and the violent doctrine of the Chicago School could not be more opposed. In another sense, however, Chilean cybernetics would serve as the prototype for a new form of governance that would finally award to the theories of the Chicago School a hegemonic control over global society. In Alleys of Your Mind: Augmented Intellligence and Its Traumas, edited by Matteo Pasquinelli, 37–51. Lüneburg: meson press, 2015. DOI: 10.14619/014 38 Alleys of Your Mind Zero Latency Agreatdealoftimehasbeenspentinvestigating,documentinganddisputing anelevenyearperiodinChilefrom1970–1981,encompassingthepresidency ofSalvadorAllendeandthedictatorshipofAugustoPinochet.Betweenthe rise of the Unidad Popular anditsoverthrowbythemilitaryjunta,brutaland notorious events took hold of Chile.1 Though many of these events have remainedambiguous,obscuredbytraumaorlostinofficialdissimulation,over timethecontoursofhistoryhavebecomelessconfused.Beyondthecoup,the involvement of the United States or even the subsequent transformation of the economy, a more comprehensive story of radical experimentation on the Chileansocialbodyhasemerged.AtstakeintheyearsofAllende’sascension to power and those that followed was nothing less than a Latin social labora- tory.Thislaboratorywasatonceoptimistic,sincere,naïve,andfinallybrutal. FewexperimentswereasaudaciousorpropheticasAllende’scybernetic program Cybersyn.