Rudolf Bahro: a Socialist Without a Working Class

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beyond Social Democracy in West Germany?

BEYOND SOCIAL DEMOCRACY IN WEST GERMANY? William Graf I The theme of transcending, bypassing, revising, reinvigorating or otherwise raising German Social Democracy to a higher level recurs throughout the party's century-and-a-quarter history. Figures such as Luxemburg, Hilferding, Liebknecht-as well as Lassalle, Kautsky and Bernstein-recall prolonged, intensive intra-party debates about the desirable relationship between the party and the capitalist state, the sources of its mass support, and the strategy and tactics best suited to accomplishing socialism. Although the post-1945 SPD has in many ways replicated these controversies surrounding the limits and prospects of Social Democracy, it has not reproduced the Left-Right dimension, the fundamental lines of political discourse that characterised the party before 1933 and indeed, in exile or underground during the Third Reich. The crucial difference between then and now is that during the Second Reich and Weimar Republic, any significant shift to the right on the part of the SPD leader- ship,' such as the parliamentary party's approval of war credits in 1914, its truck under Ebert with the reactionary forces, its periodic lapses into 'parliamentary opportunism' or the right rump's acceptance of Hitler's Enabling Law in 1933, would be countered and challenged at every step by the Left. The success of the USPD, the rise of the Spartacus move- ment, and the consistent increase in the KPD's mass following throughout the Weimar era were all concrete and determined reactions to deficiences or revisions in Social Democratic praxis. Since 1945, however, the dynamics of Social Democracy have changed considerably. -

Biografie Über Rudolf Bahro

Rudolf Bahro (1935 - 1997) Biografie Rudolf Bahro wurde am 18. November 1935 in Bad Flinsberg (heute: Swieradów Zdrój, Polen) geboren, einem damals bedeutenden Kurort im niederschlesischen Isergebirge. Sein Vater Max Bahro war als Viehwirtschaftsberater tätig, seine Mutter Irmgard kam aus einem Ort in der Umgebung. Gegen Ende des Krieges wurden die Kinder mit ihrer Mutter evakuiert. Der knapp Zehnjährige verlor seine Mutter und die beiden Geschwister in den Kriegswirren und erlebte ab Februar 1945 eine Odyssee durch verschiedene Orte in der Tschechoslowakei, die ihn über Wien und Kärnten schließlich in den Westen Deutschlands, nach Biedenkopf an der Lahn brachte. 1946 kam Rudolf Bahro dann wieder zu seinem Vater, der im Oderland das Ende des Krieges überstanden hatte und dort nun eine neue Familie gründete. Zwischen 1946 und 1950 besuchte Rudolf Bahro die Grundschule in verschiedenen Orten im Oderbruch und schließlich in Fürstenberg (heute Eisenhüttenstadt, das 1961 aus der Vereinigung von Fürstenberg mit dem 1951 gegründeten Stalinstadt entstand), anschließend – überdurchschnittlich begabt und intelligent - bis 1954 die Oberschule. Seit 1950 Mitglied der Freien Deutschen Jugend (FDJ), trat Rudolf Bahro bereits 1952 in die SED ein – gewonnen durch die Haltung eines seiner Lehrer. Als SED-Mitglied verstand sich Bahro als Teil einer bewussten Minderheit, die mit dem Staat DDR eine "übergeschichtliche Perspektive" verband. An der Berliner Humboldt-Universität studierte Rudolf Bahro von 1954 bis 1959 Philosophie, u. a. bei Hager, Scheler, Klaus und Heise. Seine Diplomarbeit schrieb er über "Johannes R. Becher und das Verhältnis der deutschen Arbeiterklasse und ihrer Partei zur nationalen Frage unseres Volkes". Nach dem Diplom ging Bahro nach Sachsendorf, in seine zweite Heimat Oderbruch, wo er u. -

I Green Politics and the Reformation of Liberal Democratic

Green Politics and the Reformation of Liberal Democratic Institutions. A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology in the University of Canterbury by R.M.Farquhar University of Canterbury 2006 I Contents. Abstract...........................................................................................................VI Introduction....................................................................................................VII Methodology....................................................................................................XIX Part 1. Chapter 1 Critical Theory: Conflict and change, marxism, Horkheimer, Adorno, critique of positivism, instrumental reason, technocracy and the Enlightenment...................................1 1.1 Mannheim’s rehabilitation of ideology and politics. Gramsci and social and political change, hegemony and counter-hegemony. Laclau and Mouffe and radical plural democracy. Talshir and modular ideology............................................................................11 Part 2. Chapter 2 Liberal Democracy: Dryzek’s tripartite conditions for democracy. The struggle for franchise in Britain and New Zealand. Extra-Parliamentary and Parliamentary dynamics. .....................29 2.1 Technocracy, New Zealand and technocracy, globalisation, legitimation crisis. .............................................................................................................................46 Chapter 3 Liberal Democracy-historical -

Was Karl Marx an Ecosocialist?

Fast Capitalism ISSN 1930-014X Volume 17 • Issue 2 • 2020 doi:10.32855/fcapital.202002.006 Was Karl Marx an Ecosocialist? Carl Boggs Facing the provocative question as to whether Karl Marx could be regarded as an ecosocialist – the very first ecosocialist – contemporary environmentalists might be excused for feeling puzzled. After all, the theory (a historic merger of socialism and ecology) did not enter Western political discourse until the late 1970s and early 1980s, when leading figures of the European Greens (Rudolf Bahro, Rainer Trampert, Thomas Ebermann) were laying the foundations of a “red-green” politics. That would be roughly one century after Marx completed his final work. Later ecological thinkers would further refine (and redefine) the outlook, among them Barry Commoner, James O’Connor, Murray Bookchin, Andre Gorz, and Joel Kovel. It would not be until the late 1990s and into the new century, however, that leftists around the journal Monthly Review (notably Paul Burkett, John Bellamy Foster, Fred Magdoff) would begin to formulate the living image of an “ecological Marx.” The most recent, perhaps most ambitious, of these projects is Kohei Saito’s Karl Marx’s Ecosocialism, an effort to reconstruct Marx’s thought from the vantage point of the current ecological crisis. Was the great Marx, who died in 1883, indeed something of an ecological radical – a theorist for whom, as Saito argues, natural relations were fundamental to understanding capitalist development? Saito’s aim was to arrive at a new reading of Marx’s writings based on previously unpublished “scientific notebooks” written toward the end of Marx’s life. -

The Challenge of Rudolf Bahro in Eastern Europe

BAHRO 17 THE CHALLENGE OF RUDOLF BAHRO IN EASTERN EUROPE Rudolf Bahro The Alternative in Eastern Europe T H E ALTERNATIVE IN communist parties and socialists in western EASTERN EUROPE by RUDOLF Europe and elsewhere. He differs from many BAHRO. New Left Books, London, 1978. others who have been imprisoned in that he remains very much a marxist and a Reviewed by DENIS FRENEY. communist, whose vision of socialism comes directly from Marx. Rudolf Bahro was released from prison in Bahro's book is immensely valuable, not the German Democratic Republic in October only for those who are concerned about the 1979, under an amnesty proclaimed on the future of socialism in Eastern Europe, the thirtieth anniversary of the founding of the Soviet Union and China, but also for those GDR. He had been arrested in August 1977, concerned more generally about the and in July 1978 was sentenced to eight transition to socialism — and communism — years’ jail for “espionage”. The act of in advanced capitalist nations and more “espionage” was the smuggling of the generally for all of humanity. Bahro's manuscript of this book to West Germany analysis intersects with this concern on such where it was published. questions as the environment, consumerism, Bahro, then, was a political prisoner. His wornetvs liberation, the division between imprisonment aroused many protests among intellectual and "manual” labor, and so on, 18 AUSTRALIAN LEFT REVIEW No. 72 with issues that have come to the fore for Soviet State has fulfilled the most important communists in countries like Australia. double function of achieving labor discipline and combatting the egalitarian tendencies of the masses. -

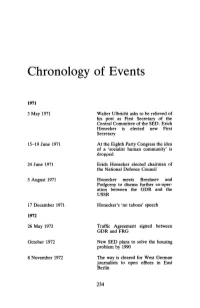

Chronology of Events

Chronology of Events 1971 3 May 1971 Walter Ulbrlcht asks to be relieved of bis post as First Secretary of the Central Committee of the SED. Erlch Honecker is elected new First Secretary 15-19 June 1971 At the Eighth Party Congress the idea of a 'socialist human community' is dropped 24 June 1971 Erlch Honecker elected chairman of the National Defence Council 5 August 1971 Honecker meets Brezhnev and Podgomy to discuss further co-oper ation between the GDR and the USSR 17 December 1971 Honecker's 'no taboos' speech 1972 26 May 1972 Trafik Agreement signed between GDRandFRG October 1972 New SED plans to solve the housing problem by 1990 8 November 1972 The way is cleared for West German journalists to open offices in East Berlin 234 Chronology 0/ Events 235 21 December 1972 Basic Treaty signed as a first step towards 'normalising' relations between GDR and FRG 1973 21 February 1973 A new regulation against foreign journalists slandering the GDR, its institutions and leading figures 1 August 1973 Walter Ulbricht dies at the age of 80 18 September 1973 East and West Germany are accepted as members of the United Nations 2 October 1973 The Central Committee approves a plan to step up the housing programme 1974 1 February 1974 East German citizens are permitted to possess Western currency 20 June 1974 Günter Gaus becomes the first 'Permanent Representative' of the FRG in the GDR 7 October 1974 Law on the revision of the constitution comes into effect. Concept of one German nation is dropped and doser ties with the Soviet Union stressed 1975 1 August 1975 Helsinki Final Act signed 7 October 1975 Treaty of Friendship, Co-operation and Mutual Aid between GDR and Soviet Union 16 December 1975 Spiegel reporter Jörg Mettke expelled after another Spiegel reporter publishes a story on compulsory adop tion in the GDR 1976 29-30 June 1976 Conference of 29 Communist and 236 Chronology 0/ Events Workers' Parties in East Berlin. -

Marxist Revisionism in East Germany: the Case of Rudolf Bahro

Marxist Revisionism in East Germany: The Case of Rudolf Bahro JEFFREY LEE CANFIELD Between August 1977 and October 1979 Rudolf Bahro's in- carcerationin East Germany for having criticizedexisting socialism drew the attention of Western Europe and much of the world. His revision of Marxism is unique because it originates within the Com- munist Bloc and because Bahro himself was a Communist Party member anda successful managerin East German industry. Jeffrey Lee Canfield recounts the details of this case andanalyzes Bahro's theory. For the last several years the internal policy of the East German regime has been undergoing another of its periodic shifts in direction. Following the de- stabilizing effects of the Helsinki Conference in 1975, the 1976 East Berlin Communist Parties meeting and the revocation of the popular singer and dissi- dent Wolf Biermann's citizenship on 16 November 1976, it appeared to most observers that the German Democratic Republic (G.D.R.) was settling into a period of relative stability in anticipation of the Thirtieth Anniversary of the Republic (celebrated on 7 October 1979). But subsequent events have indi- cated that, in fact, liberalization has not come to pass, as is clearly demon- strated by the revision and toughening of the penal code effective 1 August 1979. In the course of the shift, a novel interpretation of Marxist-Leninist theory and practice appeared in the form of a 543-page book written by a then- unknown party member and industrial manager. Since that event in the fall of 1977, Rudolf Bahro and his work, Die Alternative: zur Kritik des real existier- Jeffrey Lee Canfield is a candidate for the Master of International Affair Degree at the School for International Affairs at Columbia University. -

The Stasi at Home and Abroad the Stasi at Home and Abroad Domestic Order and Foreign Intelligence

Bulletin of the GHI | Supplement 9 the GHI | Supplement of Bulletin Bulletin of the German Historical Institute Supplement 9 (2014) The Stasi at Home and Abroad Stasi The The Stasi at Home and Abroad Domestic Order and Foreign Intelligence Edited by Uwe Spiekermann 1607 NEW HAMPSHIRE AVE NW WWW.GHI-DC.ORG WASHINGTON DC 20009 USA [email protected] Bulletin of the German Historical Institute Washington DC Editor: Richard F. Wetzell Supplement 9 Supplement Editor: Patricia C. Sutcliffe The Bulletin appears twice and the Supplement usually once a year; all are available free of charge and online at our website www.ghi-dc.org. To sign up for a subscription or to report an address change, please contact Ms. Susanne Fabricius at [email protected]. For general inquiries, please send an e-mail to [email protected]. German Historical Institute 1607 New Hampshire Ave NW Washington DC 20009-2562 Phone: (202) 387-3377 Fax: (202) 483-3430 Disclaimer: The views and conclusions presented in the papers published here are the authors’ own and do not necessarily represent the position of the German Historical Institute. © German Historical Institute 2014 All rights reserved ISSN 1048-9134 Cover: People storming the headquarters of the Ministry for National Security in Berlin-Lichtenfelde on January 15, 1990, to prevent any further destruction of the Stasi fi les then in progress. The poster on the wall forms an acrostic poem of the word Stasi, characterizing the activities of the organization as Schlagen (hitting), Treten (kicking), Abhören (monitoring), -

The East German Revolution of 1989

The East German Revolution of 1989 A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Ph.D. in the Faculty of Economic and Social Studies. Gareth Dale, Department of Government, September 1999. Contents List of Tables 3 Declaration and Copyright 5 Abstract 6 Abbreviations, Acronyms, Glossary and ‘Who’s Who’ 8 Preface 12 1. Introduction 18 2. Capitalism and the States-system 21 (i) Competition and Exploitation 22 (ii) Capitalism and States 28 (iii) The Modern World 42 (iv) Political Crisis and Conflict 61 3. Expansion and Crisis of the Soviet-type Economies 71 4. East Germany: 1945 to 1975 110 5. 1975 to June 1989: Cracks Beneath the Surface 147 (i) Profitability Decline 147 (ii) Between a Rock and a Hard Place 159 (iii) Crisis of Confidence 177 (iv) Terminal Crisis: 1987-9 190 6. Scenting Opportunity, Mobilizing Protest 215 7. The Wende and the Fall of the Wall 272 8. Conclusion 313 Bibliography 322 2 List of Tables Table 2.1 Government spending as percentage of GDP; DMEs 50 Table 3.1 Consumer goods branches, USSR 75 Table 3.2 Producer and consumer goods sectors, GDR 75 Table 3.3 World industrial and trade growth 91 Table 3.4 Trade in manufactures as proportion of world output 91 Table 3.5 Foreign trade growth of USSR and six European STEs 99 Table 3.6 Joint ventures 99 Table 3.7 Net debt of USSR and six European STEs 100 Table 4.1 Crises, GDR, 1949-88 127 Table 4.2 Economic crisis, 1960-2 130 Table 4.3 East Germans’ faith in socialism 140 Table 4.4 Trade with DMEs 143 Table 5.1 Rate of accumulation 148 Table 5.2 National -

The Old GDR Opposition in the New Germany

GDR Bulletin Volume 18 Issue 1 Spring Article 5 1992 The Old GDR Opposition in the New Germany Roger Woods Aston University Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/gdr This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Woods, Roger (1992) "The Old GDR Opposition in the New Germany," GDR Bulletin: Vol. 18: Iss. 1. https://doi.org/10.4148/gdrb.v18i1.1027 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in GDR Bulletin by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact cads@k- state.edu. Woods: The Old GDR Opposition in the New Germany ahlesbar, alles ist korrekt verzeichnet, aber in eine so abstrakte niemals den logischen Bruch der Gesamtlüge aufscheinen Nomenklatur verhüllt, daß man nichts mehr verstehen konnte. lassen durften. So betrog die Staatssicherheit sich selbst und Die zweiwertige formale Logik der Glanzzeit des die Partei, der sie Schild und Schwert sein wollte und doch Realsozialismus (Hauptfrage ist: Wer wen?) wandelte sich in letzten Endes nur ihr Papertigerbild zustande brachte. das milchige Licht einer Realitätsbeschreibung, in der die Vorinterpretation so versteckt wurde, daß die Wahrheitsfindung Taken from Jens Reich: ABSCHIED VON DEN LEBENSLÜGEN. im Ermessen des sklerotischen Generalsekretärs lag. Copyright (c) 1992 by Rowohlt Berlin Verlag GmbH, Berlin. So sammelte die Stasi Informationen, die niemals Reprinted with permission Informationen sein durften. So ermittelte sie Wahrheiten, die The Old GDR Opposition in the New Germany Roger Woods The critical left which was opposed to the old SED has Aston University, GB experienced its own problems. -

East German Intellectuals and Public Discourses in the 1950S

East German Intellectuals and Public Discourses in the 1950s Wieland Herzfelde, Erich Loest and Peter Hacks Hidde van der Wall, MA Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2013 1 To the memory of my parents 2 Table of Contents Abstract 5 Publications arising from this thesis 6 Acknowledgements 7 1. Introduction 9 1. Selection of authors and source material 10 2. The contested memory of the GDR 13 3. Debating the role of intellectuals in the GDR 21 4. The 1950s: debates, events, stages 37 5. The generational paradigm 53 2. Wieland Herzfelde: Reforming Party discourses from within 62 1. Introduction 62 2. Ambiguous communist involvement before 1949 67 3. Return to an antifascist homeland 72 4. Aesthetics: Defending a legacy 78 5. Affirmative stances in the lectures 97 6. The June 1953 uprising 102 7. German Division and the Cold War 107 8. The contexts of criticism in 1956-1957 126 9. Conclusion 138 3 3. Erich Loest: Dissidence and conformity 140 1. Introduction 140 2. Aesthetics: Entertainment, positive heroes, factography 146 3. Narrative fiction 157 4. Consensus and dissent: 1953 183 5. War stories 204 6. Political opposition 216 7. Conclusion 219 4. Peter Hacks: Political aesthetics 222 1. Introduction 222 2. Political affirmation 230 3. Aesthetics: A programme for a socialist theatre 250 4. Intervening in the debate on didactic theatre 270 5. Two ‗dialectical‘ plays 291 6. Conclusion 298 5. Conclusion 301 Bibliography 313 4 Abstract The aim of this thesis is to contribute to a differentiated reassessment of the cultural history of the German Democratic Republic (GDR), which has hitherto been hampered by critical approaches which have the objective of denouncing rather than understanding East German culture and society. -

Criticism/Self-Criticism in East Germany: Contradictions Between Theory and Practice Year of Publication: 1998 Citation: Andrews, M

University of East London Institutional Repository: http://roar.uel.ac.uk This paper is made available online in accordance with publisher policies. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item and our policy information available from the repository home page for further information. To see the final version of this paper please visit the publisher’s website. Access to the published version may require a subscription. Author(s): Andrews, Molly. Article Title: Criticism/self-Criticism in East Germany: Contradictions between theory and practice Year of publication: 1998 Citation: Andrews, M. (1998) ‘Criticism/self-Criticism in East Germany: Contradictions between theory and practice’ Critical Sociology 24 (1-2) 130-153 Link to published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/089692059802400107 DOI: 10.1177/089692059802400107 Andrews, M. (1998) "Criticism/self-Criticism in East Germany: Contradictions between theory and practice" Critical Sociology 24/1-2. Criticism/Self-Criticism in East Germany: Contradictions between Theory and Practice On November 4, 1989, Christoph Hein, East German author and internal critic, stood at the podium in Berlin's Alexanderplatz, and asked of the half million protesters gathered there to "imagine a socialism where nobody ran away." Five days later, on the same day that the wall was opened, leaders of the main opposition groups issued a public appeal called "For Our Country" reflecting a fidelity to the principles of socialism: We ask of you, remain in your homeland, stay here by us... Help us to construct a truly democratic socialism. It is no dream, if you work with us to prevent it from again being strangled at birth.