Apiaceae (Umbelliferae) the Carrot Or Parsley Family

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carrot Butter–Poached Halibut, Anchovy-Roasted Carrots, Fennel

Carrot Butter–Poached Halibut, Anchovy-Roasted Carrots, Fennel 2 pounds (900 g) small carrots, with tops 31⁄2 cups (875 g) unsalted butter 3 anchovy fillets, minced 3 lemons Kosher salt 2 cups (500 ml) fresh carrot juice 3 cloves garlic, crushed, plus 1 whole clove garlic 1 bay leaf Zest of 1 orange 1⁄4 cup (60 ml) extra-virgin olive oil 4 halibut fillets, each about 6 ounces (185 g) Maldon flake salt Fennel Salad 1 fennel bulb, sliced 1⁄8 inch (3 mm) thick using a mandoline 2 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil 2 tablespoons chopped chives 1 tablespoon chopped white anchovies (boquerones) Kosher salt and freshly ground black Pepper 1. Preheat the oven to 350°F (180°C). 2. Remove the carrot tops, wash, and set aside. Peel the carrots and halve them lengthwise. In a saute pan over medium heat, melt . cup (125 g) of the butter with the anchovies and the grated zest from two of the lemons. Add the carrots and season with kosher salt. Transfer to a baking sheet, spread in a single layer, and roast in the oven until slightly softened but still a little crunchy, about 12 minutes. Remove from oven and toss with the juice of one lemon. 3. In a shallow saute pan over medium heat, combine the carrot juice, the crushed garlic, bay leaf, and orange zest. Cook until reduced by threequarters, about 10 minutes. Add the remaining 3 cups (750 g) butter and stir until melted, then reduce the heat to very low and keep warm. -

Poisonous Plants of the Southern United States

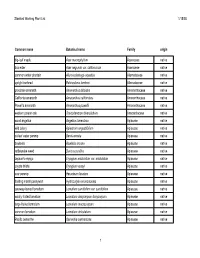

Poisonous Plants of the Southern United States Poisonous Plants of the Southern United States Common Name Genus and Species Page atamasco lily Zephyranthes atamasco 21 bitter sneezeweed Helenium amarum 20 black cherry Prunus serotina 6 black locust Robinia pseudoacacia 14 black nightshade Solanum nigrum 16 bladderpod Glottidium vesicarium 11 bracken fern Pteridium aquilinum 5 buttercup Ranunculus abortivus 9 castor bean Ricinus communis 17 cherry laurel Prunus caroliniana 6 chinaberry Melia azederach 14 choke cherry Prunus virginiana 6 coffee senna Cassia occidentalis 12 common buttonbush Cephalanthus occidentalis 25 common cocklebur Xanthium pensylvanicum 15 common sneezeweed Helenium autumnale 19 common yarrow Achillea millefolium 23 eastern baccharis Baccharis halimifolia 18 fetterbush Leucothoe axillaris 24 fetterbush Leucothoe racemosa 24 fetterbush Leucothoe recurva 24 great laurel Rhododendron maxima 9 hairy vetch Vicia villosa 27 hemp dogbane Apocynum cannabinum 23 horsenettle Solanum carolinense 15 jimsonweed Datura stramonium 8 johnsongrass Sorghum halepense 7 lantana Lantana camara 10 maleberry Lyonia ligustrina 24 Mexican pricklepoppy Argemone mexicana 27 milkweed Asclepias tuberosa 22 mountain laurel Kalmia latifolia 6 mustard Brassica sp . 25 oleander Nerium oleander 10 perilla mint Perilla frutescens 28 poison hemlock Conium maculatum 17 poison ivy Rhus radicans 20 poison oak Rhus toxicodendron 20 poison sumac Rhus vernix 21 pokeberry Phytolacca americana 8 rattlebox Daubentonia punicea 11 red buckeye Aesculus pavia 16 redroot pigweed Amaranthus retroflexus 18 rosebay Rhododendron calawbiense 9 sesbania Sesbania exaltata 12 scotch broom Cytisus scoparius 13 sheep laurel Kalmia angustifolia 6 showy crotalaria Crotalaria spectabilis 5 sicklepod Cassia obtusifolia 12 spotted water hemlock Cicuta maculata 17 St. John's wort Hypericum perforatum 26 stagger grass Amianthum muscaetoxicum 22 sweet clover Melilotus sp . -

Carrots, Celery, Dehydration & Osmosis

CARROTS, CELERY, DEHYDRATION & OSMOSIS OVERVIEW Students will investigate dehydration by soaking carrots and celery in salt and fresh water and observing the effects of osmosis on living organisms. Animals and plants that live in the ocean usually have a high salt level within them in order to avoid dehydration. CONCEPTS • Water molecules move across a membrane to higher levels of salt concentration through a pro- cess called osmosis. • Animals and plants that live in the ocean usually have a high salt content. On the other hand, animals and plants that are not adapted to salt water may have a low salt content, and thus become dehydrated when placed in salt water. MATERIALS For each group: • Salt water • Fresh water • Carrots • Celery • Containers (bowls, glasses, cups) PREPARATION Salt water can be created by simply putting a large quantity of salt into some water and stirring. Warm water will cause the salt to dissolve easier. If you wish to simulate the salt content of the ocean (optional), put 35 milligrams of salt into 965 milliliters of water. This exercise can be done as a class activity/demonstration, or students can be split into small groups. Each group will need a full set of materials. There should be at least one period where the vegetables are left in water for an extended period to get the desired effect. You may therefore wish to extend this activity throughout the day, or for more dramatic and distinctive results, conduct it over two to three days. Alternatively, you can reduce the time needed for this activity if you begin with both crisp and limp vegetables. -

The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts

The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts: The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts: A County Checklist • First Revision Melissa Dow Cullina, Bryan Connolly, Bruce Sorrie and Paul Somers Somers Bruce Sorrie and Paul Connolly, Bryan Cullina, Melissa Dow Revision • First A County Checklist Plants of Massachusetts: Vascular The A County Checklist First Revision Melissa Dow Cullina, Bryan Connolly, Bruce Sorrie and Paul Somers Massachusetts Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program The Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program (NHESP), part of the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, is one of the programs forming the Natural Heritage network. NHESP is responsible for the conservation and protection of hundreds of species that are not hunted, fished, trapped, or commercially harvested in the state. The Program's highest priority is protecting the 176 species of vertebrate and invertebrate animals and 259 species of native plants that are officially listed as Endangered, Threatened or of Special Concern in Massachusetts. Endangered species conservation in Massachusetts depends on you! A major source of funding for the protection of rare and endangered species comes from voluntary donations on state income tax forms. Contributions go to the Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Fund, which provides a portion of the operating budget for the Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program. NHESP protects rare species through biological inventory, -

Apiaceae) - Beds, Old Cambs, Hunts, Northants and Peterborough

CHECKLIST OF UMBELLIFERS (APIACEAE) - BEDS, OLD CAMBS, HUNTS, NORTHANTS AND PETERBOROUGH Scientific name Common Name Beds old Cambs Hunts Northants and P'boro Aegopodium podagraria Ground-elder common common common common Aethusa cynapium Fool's Parsley common common common common Ammi majus Bullwort very rare rare very rare very rare Ammi visnaga Toothpick-plant very rare very rare Anethum graveolens Dill very rare rare very rare Angelica archangelica Garden Angelica very rare very rare Angelica sylvestris Wild Angelica common frequent frequent common Anthriscus caucalis Bur Chervil occasional frequent occasional occasional Anthriscus cerefolium Garden Chervil extinct extinct extinct very rare Anthriscus sylvestris Cow Parsley common common common common Apium graveolens Wild Celery rare occasional very rare native ssp. Apium inundatum Lesser Marshwort very rare or extinct very rare extinct very rare Apium nodiflorum Fool's Water-cress common common common common Astrantia major Astrantia extinct very rare Berula erecta Lesser Water-parsnip occasional frequent occasional occasional x Beruladium procurrens Fool's Water-cress x Lesser very rare Water-parsnip Bunium bulbocastanum Great Pignut occasional very rare Bupleurum rotundifolium Thorow-wax extinct extinct extinct extinct Bupleurum subovatum False Thorow-wax very rare very rare very rare Bupleurum tenuissimum Slender Hare's-ear very rare extinct very rare or extinct Carum carvi Caraway very rare very rare very rare extinct Chaerophyllum temulum Rough Chervil common common common common Cicuta virosa Cowbane extinct extinct Conium maculatum Hemlock common common common common Conopodium majus Pignut frequent occasional occasional frequent Coriandrum sativum Coriander rare occasional very rare very rare Daucus carota Wild Carrot common common common common Eryngium campestre Field Eryngo very rare, prob. -

Flowering Plants Eudicots Apiales, Gentianales (Except Rubiaceae)

Edited by K. Kubitzki Volume XV Flowering Plants Eudicots Apiales, Gentianales (except Rubiaceae) Joachim W. Kadereit · Volker Bittrich (Eds.) THE FAMILIES AND GENERA OF VASCULAR PLANTS Edited by K. Kubitzki For further volumes see list at the end of the book and: http://www.springer.com/series/1306 The Families and Genera of Vascular Plants Edited by K. Kubitzki Flowering Plants Á Eudicots XV Apiales, Gentianales (except Rubiaceae) Volume Editors: Joachim W. Kadereit • Volker Bittrich With 85 Figures Editors Joachim W. Kadereit Volker Bittrich Johannes Gutenberg Campinas Universita¨t Mainz Brazil Mainz Germany Series Editor Prof. Dr. Klaus Kubitzki Universita¨t Hamburg Biozentrum Klein-Flottbek und Botanischer Garten 22609 Hamburg Germany The Families and Genera of Vascular Plants ISBN 978-3-319-93604-8 ISBN 978-3-319-93605-5 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-93605-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018961008 # Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature 2018 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. -

FLORA from FĂRĂGĂU AREA (MUREŞ COUNTY) AS POTENTIAL SOURCE of MEDICINAL PLANTS Silvia OROIAN1*, Mihaela SĂMĂRGHIŢAN2

ISSN: 2601 – 6141, ISSN-L: 2601 – 6141 Acta Biologica Marisiensis 2018, 1(1): 60-70 ORIGINAL PAPER FLORA FROM FĂRĂGĂU AREA (MUREŞ COUNTY) AS POTENTIAL SOURCE OF MEDICINAL PLANTS Silvia OROIAN1*, Mihaela SĂMĂRGHIŢAN2 1Department of Pharmaceutical Botany, University of Medicine and Pharmacy of Tîrgu Mureş, Romania 2Mureş County Museum, Department of Natural Sciences, Tîrgu Mureş, Romania *Correspondence: Silvia OROIAN [email protected] Received: 2 July 2018; Accepted: 9 July 2018; Published: 15 July 2018 Abstract The aim of this study was to identify a potential source of medicinal plant from Transylvanian Plain. Also, the paper provides information about the hayfields floral richness, a great scientific value for Romania and Europe. The study of the flora was carried out in several stages: 2005-2008, 2013, 2017-2018. In the studied area, 397 taxa were identified, distributed in 82 families with therapeutic potential, represented by 164 medical taxa, 37 of them being in the European Pharmacopoeia 8.5. The study reveals that most plants contain: volatile oils (13.41%), tannins (12.19%), flavonoids (9.75%), mucilages (8.53%) etc. This plants can be used in the treatment of various human disorders: disorders of the digestive system, respiratory system, skin disorders, muscular and skeletal systems, genitourinary system, in gynaecological disorders, cardiovascular, and central nervous sistem disorders. In the study plants protected by law at European and national level were identified: Echium maculatum, Cephalaria radiata, Crambe tataria, Narcissus poeticus ssp. radiiflorus, Salvia nutans, Iris aphylla, Orchis morio, Orchis tridentata, Adonis vernalis, Dictamnus albus, Hammarbya paludosa etc. Keywords: Fărăgău, medicinal plants, human disease, Mureş County 1. -

Alphabetical Lists of the Vascular Plant Families with Their Phylogenetic

Colligo 2 (1) : 3-10 BOTANIQUE Alphabetical lists of the vascular plant families with their phylogenetic classification numbers Listes alphabétiques des familles de plantes vasculaires avec leurs numéros de classement phylogénétique FRÉDÉRIC DANET* *Mairie de Lyon, Espaces verts, Jardin botanique, Herbier, 69205 Lyon cedex 01, France - [email protected] Citation : Danet F., 2019. Alphabetical lists of the vascular plant families with their phylogenetic classification numbers. Colligo, 2(1) : 3- 10. https://perma.cc/2WFD-A2A7 KEY-WORDS Angiosperms family arrangement Summary: This paper provides, for herbarium cura- Gymnosperms Classification tors, the alphabetical lists of the recognized families Pteridophytes APG system in pteridophytes, gymnosperms and angiosperms Ferns PPG system with their phylogenetic classification numbers. Lycophytes phylogeny Herbarium MOTS-CLÉS Angiospermes rangement des familles Résumé : Cet article produit, pour les conservateurs Gymnospermes Classification d’herbier, les listes alphabétiques des familles recon- Ptéridophytes système APG nues pour les ptéridophytes, les gymnospermes et Fougères système PPG les angiospermes avec leurs numéros de classement Lycophytes phylogénie phylogénétique. Herbier Introduction These alphabetical lists have been established for the systems of A.-L de Jussieu, A.-P. de Can- The organization of herbarium collections con- dolle, Bentham & Hooker, etc. that are still used sists in arranging the specimens logically to in the management of historical herbaria find and reclassify them easily in the appro- whose original classification is voluntarily pre- priate storage units. In the vascular plant col- served. lections, commonly used methods are systema- Recent classification systems based on molecu- tic classification, alphabetical classification, or lar phylogenies have developed, and herbaria combinations of both. -

Conserving Europe's Threatened Plants

Conserving Europe’s threatened plants Progress towards Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation Conserving Europe’s threatened plants Progress towards Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation By Suzanne Sharrock and Meirion Jones May 2009 Recommended citation: Sharrock, S. and Jones, M., 2009. Conserving Europe’s threatened plants: Progress towards Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation Botanic Gardens Conservation International, Richmond, UK ISBN 978-1-905164-30-1 Published by Botanic Gardens Conservation International Descanso House, 199 Kew Road, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 3BW, UK Design: John Morgan, [email protected] Acknowledgements The work of establishing a consolidated list of threatened Photo credits European plants was first initiated by Hugh Synge who developed the original database on which this report is based. All images are credited to BGCI with the exceptions of: We are most grateful to Hugh for providing this database to page 5, Nikos Krigas; page 8. Christophe Libert; page 10, BGCI and advising on further development of the list. The Pawel Kos; page 12 (upper), Nikos Krigas; page 14: James exacting task of inputting data from national Red Lists was Hitchmough; page 16 (lower), Jože Bavcon; page 17 (upper), carried out by Chris Cockel and without his dedicated work, the Nkos Krigas; page 20 (upper), Anca Sarbu; page 21, Nikos list would not have been completed. Thank you for your efforts Krigas; page 22 (upper) Simon Williams; page 22 (lower), RBG Chris. We are grateful to all the members of the European Kew; page 23 (upper), Jo Packet; page 23 (lower), Sandrine Botanic Gardens Consortium and other colleagues from Europe Godefroid; page 24 (upper) Jože Bavcon; page 24 (lower), Frank who provided essential advice, guidance and supplementary Scumacher; page 25 (upper) Michael Burkart; page 25, (lower) information on the species included in the database. -

La Cicuta: Poison Hemlock

ALERTA DE MALA HIERBA NOCIVA EN EL CONDADO DE KING Cicuta Mala hierba nociva no regulada de Clase B: Poison Hemlock Control recomendado Conium maculatum Familia Apiaceae Cómo identificarla • Bienal que alcanza de 8 (2.4 m) a 10 pies (3 m) de altura el segundo año. • Hojas color verde encendido tipo helecho con un fuerte olor a moho • El primer año, las plantas forman rosetas basales de hojas muy divididas y tallos rojizos con motas • El segundo año, los tallos son fuertes, huecos, sin pelos, con nervaduras y con motas/rayas rojizas o púrpuras • Plantas con flores cubiertas con numerosos racimos pequeños con forma de paraguas de diminutas flores blancas de cinco pétalos • Las semillas se forman en cápsulas verdes y acanaladas que con el tiempo La cicuta tiene hojas de color verde se vuelven marrones brillante, tipo helecho con olor a moho. Biología Se reproduce por semilla. El primer año crece en forma de roseta; el segundo, desarrolla tallos altos y flores. Crece rápidamente entre marzo y mayo; florece a finales de la primavera. Cada planta produce hasta 40,000 semillas. Las semillas caen cerca de la planta y se desplazan por la erosión, los animales, la lluvia y la actividad humana. Las semillas son viables hasta por 6 años y germinan durante la temporada de crecimiento; no requieren un periodo de letargo. Impacto Altamente tóxica para el ser humano, el ganado y la vida silvestre; causa Los tallos gruesos y sin pelos tienen la muerte por parálisis respiratoria tras su ingestión. El crecimiento manchas o vetas de color púrpura o rojizo. -

Aegopodium Podagraria

Aegopodium podagraria INTRODUCTORY DISTRIBUTION AND OCCURRENCE BOTANICAL AND ECOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS FIRE EFFECTS AND MANAGEMENT MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS APPENDIX: FIRE REGIME TABLE REFERENCES INTRODUCTORY AUTHORSHIP AND CITATION FEIS ABBREVIATION NRCS PLANT CODE COMMON NAMES TAXONOMY SYNONYMS LIFE FORM Variegated goutweed. All-green goutweed. Photos by John Randall, The Nature Conservancy, Bugwood.org AUTHORSHIP AND CITATION: Waggy, Melissa, A. 2010. Aegopodium podagraria. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/ [ 2010, January 21]. FEIS ABBREVIATION: AEGPOD NRCS PLANT CODE [87]: AEPO COMMON NAMES: goutweed bishop's goutweed bishop's weed bishopsweed ground elder herb Gerard TAXONOMY: The scientific name of goutweed is Aegopodium podagraria L. (Apiaceae) [40]. SYNONYMS: Aegopodium podagraria var. podagraria [71] Aegopodium podagraria var. variegatum Bailey [40,71] LIFE FORM: Forb DISTRIBUTION AND OCCURRENCE SPECIES: Aegopodium podagraria GENERAL DISTRIBUTION HABITAT TYPES AND PLANT COMMUNITIES GENERAL DISTRIBUTION: Goutweed was introduced in North America from Europe [82]. In the United States, goutweed occurs from Maine south to South Carolina and west to Minnesota and Missouri. It also occurs in the Pacific Northwest from Montana to Washington and Oregon. It occurs in all the Canadian provinces excepting Newfoundland and Labrador, and Alberta. Plants Database provides a distributional map of goutweed. Globally, goutweed occurs primarily in the northern hemisphere, particularly in Europe, Asia Minor ([28,36,58,92], reviews by [14,27]), and Russia (review by [27,63]). Goutweed's native distribution is unclear. It may have been introduced in England (review by [2]) and is considered a "weed" in the former Soviet Union, Germany, Finland (Holm 1979 cited in [14]), and Poland [44]. -

Plant List for Web Page

Stanford Working Plant List 1/15/08 Common name Botanical name Family origin big-leaf maple Acer macrophyllum Aceraceae native box elder Acer negundo var. californicum Aceraceae native common water plantain Alisma plantago-aquatica Alismataceae native upright burhead Echinodorus berteroi Alismataceae native prostrate amaranth Amaranthus blitoides Amaranthaceae native California amaranth Amaranthus californicus Amaranthaceae native Powell's amaranth Amaranthus powellii Amaranthaceae native western poison oak Toxicodendron diversilobum Anacardiaceae native wood angelica Angelica tomentosa Apiaceae native wild celery Apiastrum angustifolium Apiaceae native cutleaf water parsnip Berula erecta Apiaceae native bowlesia Bowlesia incana Apiaceae native rattlesnake weed Daucus pusillus Apiaceae native Jepson's eryngo Eryngium aristulatum var. aristulatum Apiaceae native coyote thistle Eryngium vaseyi Apiaceae native cow parsnip Heracleum lanatum Apiaceae native floating marsh pennywort Hydrocotyle ranunculoides Apiaceae native caraway-leaved lomatium Lomatium caruifolium var. caruifolium Apiaceae native woolly-fruited lomatium Lomatium dasycarpum dasycarpum Apiaceae native large-fruited lomatium Lomatium macrocarpum Apiaceae native common lomatium Lomatium utriculatum Apiaceae native Pacific oenanthe Oenanthe sarmentosa Apiaceae native 1 Stanford Working Plant List 1/15/08 wood sweet cicely Osmorhiza berteroi Apiaceae native mountain sweet cicely Osmorhiza chilensis Apiaceae native Gairdner's yampah (List 4) Perideridia gairdneri gairdneri Apiaceae