Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REFERENCE DOCUMENT Containing the Annual Financial Report Fiscal Year 2016 PROFILE

REFERENCE DOCUMENT containing the Annual Financial Report Fiscal Year 2016 PROFILE The Lagardère group is a global leader in content publishing, production, broadcasting and distribution, whose powerful brands leverage its virtual and physical networks to attract and enjoy qualifi ed audiences. The Group’s business model relies on creating a lasting and exclusive relationship between the content it offers and its customers. It is structured around four business divisions: • Books and e-Books: Lagardère Publishing • Travel Essentials, Duty Free & Fashion, and Foodservice: Lagardère Travel Retail • Press, Audiovisual (Radio, Television, Audiovisual Production), Digital and Advertising Sales Brokerage: Lagardère Active • Sponsorship, Content, Consulting, Events, Athletes, Stadiums, Shows, Venues and Artists: Lagardère Sports and Entertainment 1945: at the end of World 1986: Hachette regains 26 March 2003: War II, Marcel Chassagny founds control of Europe 1. Arnaud Lagardère is appointed Matra (Mécanique Aviation Managing Partner of TRAction), a company focused 10 February 1988: Lagardère SCA. on the defence industry. Matra is privatised. 2004: the Group acquires 1963: Jean-Luc Lagardère 30 December 1992: a portion of Vivendi Universal becomes Chief Executive Publishing’s French and following the failure of French Offi cer of Matra, which Spanish assets. television channel La Cinq, has diversifi ed into aerospace Hachette is merged into Matra and automobiles. to form Matra-Hachette, 2007: the Group reorganises and Lagardère Groupe, a French around four major institutional 1974: Sylvain Floirat asks partnership limited by shares, brands: Lagardère Publishing, Jean-Luc Lagardère to head is created as the umbrella Lagardère Services (which the Europe 1 radio network. company for the entire became Lagardère Travel Retail ensemble. -

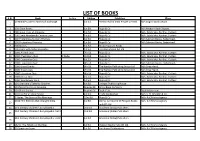

List of Books S.N

LIST OF BOOKS S.N. Book Author Edition Publisher Place 10 Minute Guide to Microsoft Exchange. 1st Ed. Prentic-Hall of India Private Limited. M/s English Book Depot 1 2 100 Great Books. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s Modern Book Depote, 3 100 Great Lives of Antiquity. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 4 100 Great Nineteenth Century Lives. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 5 100 Pretentious Nursery Rhymes. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s Sabnam Books, Badambadi, 6 100 Pretentious Proverbs. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s Sabnam Books, Badambadi, 7 100 Stories. 1st Ed. Better Yourself Books 8 100 Years with Nobel Laureates. 1st Ed. I K International Pvt Ltd 9 1000 Animal Quiz. 7th Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 10 1000 Chemistery Quiz. C Dube 3rd Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 11 1000 Economics Quiz. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 12 1000 Economics Quiz. 4th Ed. Rupa & Co M/s Sabnam Books, Badambadi, 13 1000 Great Events. 6th Ed. The Hamlyn Publishing Group Ltd. M/s Dreamland, 14 1000 Great Lives. 7th Ed. The Hamlyn Publishing Group Ltd. M/s Dreamland, 15 1000 Literature Quiz. 4th Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 16 1000 Orissa Quiz. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 17 1000 Wordpower Quiz. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 18 101 Grandma's Tales for Children. 1st Ed. Dhingra Publishing House 19 101 Moral Stories of Grandpa. -

Recieved Notice Today That It Did Not Go Through

Scientists are People, Too: Biographies of Astronomical Scientists as a Literary Introduction to the Heliocentric Theory Autry McMorris Welch Middle School INTRODUCTION The Setting and Objectives One of the teaching tools that teachers often use is to take advantage of their students’ prior knowledge. This allows students to connect with the author or subject. Many students have had astronomical awareness or experiences as simple as Aristotle’s in 320 BC – that the Earth must be round because it casts a crescent shape on the moon. For me, it was an incidental thing that I sometimes noticed the moon out in the mornings and evenings when I walked my dogs. Almost as a type of entertainment, I started to anticipate where the moon would be positioned on my next walk. I found myself exhilarated as I could correctly anticipate its position. The key for me was that the moon was moving west, but because of the Earth’s rotation, it appeared to be moving east. At that moment, I shared an icon of truth with the great masters. Astronomy is very complex, to say the least. Some students, aware of their limitations, would not begin to broach the subject except from a non-threatening position. What if an introductory course were to be available that introduced the periphery of the subject? What if selected writings, biographies, autobiographies, theories and the like were a part of a curriculum to superimpose our literary devices of today on great works that were written hundreds of years ago? Copernicus described himself somewhat as candid and clear enough that both the unlearned as well as the learned might see that he was not seeking to flee from the judgment of any man, even if someone provided a guard against the bites of slanderers, the proverb holds that there is no medicine for the bite of a sycophant. -

Sources: Galileo's Correspondence

Sources: Galileo’s Correspondence Notes on the Translations The following collection of letters is the result of a selection made by the author from the correspondence of Galileo published by Antonio Favaro in his Le opere di Galileo Galilei,theEdizione Nazionale (EN), the second edition of which was published in 1968. These letters have been selected for their relevance to the inves- tigation of Galileo’s practical activities.1 The information they contain, moreover, often refers to subjects that are completely absent in Galileo’s publications. All of the letters selected are quoted in the work. The passages of the letters, which are quoted in the work, are set in italics here. Given the particular relevance of these letters, they have been translated into English for the first time by the author. This will provide the international reader with the opportunity to achieve a deeper comprehension of the work on the basis of the sources. The translation in itself, however, does not aim to produce a text that is easily read by a modern reader. The aim is to present an understandable English text that remains as close as possible to the original. The hope is that the evident disadvantage of having, for example, long and involute sentences using obsolete words is compensated by the fact that this sort of translation reduces to a minimum the integration of the interpretation of the translator into the English text. 1Another series of letters selected from Galileo’s correspondence and relevant to Galileo’s practical activities and, in particular, as a bell caster is published appended to Valleriani (2008). -

AP European History 2019 Free-Response Questions

2019 AP® European History Free-Response Questions © 2019 The College Board. College Board, Advanced Placement, AP, AP Central, and the acorn logo are registered trademarks of the College Board. Visit the College Board on the web: collegeboard.org. AP Central is the official online home for the AP Program: apcentral.collegeboard.org. 2019 AP® EUROPEAN HISTORY FREE-RESPONSE QUESTIONS EUROPEAN HISTORY SECTION I, Part B Time—40 minutes Directions: Answer Question 1 and Question 2. Answer either Question 3 or Question 4. Write your responses in the Section I, Part B: Short-Answer Response booklet. You must write your response to each question on the lined page designated for that response. Each response is expected to fit within the space provided. In your responses, be sure to address all parts of the questions you answer. Use complete sentences; an outline or bulleted list alone is not acceptable. You may plan your answers in this exam booklet, but no credit will be given for notes written in this booklet. Use the passage below to answer all parts of the question that follows. “It was the weakness of Russia’s democratic culture which enabled Bolshevism to take root....The Russian people were trapped by the tyranny of their own history....For while the people could destroy the old system, they could not build a new one of their own....By 1921, if not earlier, the revolution had come full circle, and a new autocracy had been imposed on Russia which in many ways resembled the old.” Orlando Figes, historian, A People’s Tragedy: The Russian Revolution, 1891-1924, published in 1997 1. -

Milestonesofmannedflight World

' J/ILESTONES of JfANNED i^LIGHT With a short dash down the runway, the machine lifted into the air and was flying. It was only a flight of twelve seconds, and it was an uncertain, waiy. creeping sort offlight at best: but it was a realflight at last and not a glide. ORV1U.E VPRK.HT A DIRECT RESULT OF OnUle Wright's intrepid 12- second A flight on Kill Devil Hill in 1903. mankind, in the space of just nine decades, has developed the means to leave the boundaries of Earth, visit space and return. As a matter of routine, even- )ear millions of business people and tourists travel to the furthest -^ reaches of our planet within a matter of hours - some at twice the speed of sound. The progress has, quite simpl) . been astonishing. Having discovered the means of controlled flight in a powered, heavier-than-air machine, other uses than those of transpon were inevitable and research into the militan- potential of manned flight began almost immediatel>-. The subsequent effect of aviation on warfare has been nothing shon of revolutionary', and in most of the years since 1903 the leading technological innovations have resulted from militan- research programs. In Milestones of Manned Flight, aviation expen Mike .Spick has selected the -iO-plus events, both civil and militan-, which he considers to mark the most significant points of aviation histon-. Each one is illustrated, and where there have been significant related developments from that particular milestone, then these are featured too. From the intrepid and pioneering Wright brothers to the high-technology' gurus developing the F-22 Advanced Tactical Fighter, the histon' of manned flight is. -

Behind the Scenes at Galileo's Trial

Blackwell-000.FM 7/3/06 12:24 PM Page iii BEHIND THE SCENES AT GALILEO’S TRIAL Including the First English Translation of Melchior Inchofer’s Tractatus syllepticus RICHARD J. BLACKWELL University of Notre Dame Press Notre Dame, Indiana © 2006 University of Notre Dame Press Blackwell-000.FM 7/3/06 12:24 PM Page iv Copyright © 2006 University of Notre Dame Notre Dame, Indiana 46556 All Rights Reserved www.undpress.nd.edu Manufactured in the United States of America Behind the Scenes at Galileo’s Trial was designed by Jane Oslislo; composed in 10/13.3 Fairfield Light by Four Star Books; printed on 50# Nature’s Natural (50% pcr) by Thomson-Shore, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Blackwell, Richard J., 1929– Behind the scenes at Galileo’s trial : including the first English translation of Melchior Inchofer’s Tractatus syllepticus / Richard J. Blackwell. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and indexes. isbn-13: 978-0-268-02201-3 (acid-free paper) isbn-10: 0-268-02201-1 (acid-free paper) 1. Galilei, Galileo, 1564–1642—Trials, litigation, etc. 2. Religion and science— History—17th century. 3. Inchofer, Melchior, 1585?–1648. Tractatus syllepticus. 4. Catholic Church—Doctrines—History—17th century. 5. Inquisition—Italy. I. Inchofer, Melchior, 1585?–1648. Tractatus syllepticus. English. II. Title. qb36.g2b573 2006 520.92—dc22 2006016783 ∞The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. © 2006 University of Notre Dame Press Blackwell-01 5/18/06 10:01 PM Page 1 chapter one The Legal Case at Galileo’s Trial Impasse and Perfidy galileo’s trial before the roman inquisition is one of the most frequently mentioned topics in the history of science. -

Document De Référence 2016 Lagardère

DOCUMENT DE RÉFÉRENCE contenant un Rapport fi nancier annuel Exercice 2016 PROFIL Le groupe Lagardère est un des leaders mondiaux de l’édition, la production, la diffusion et la distribution de contenus dont les marques fortes génèrent et rencontrent des audiences qualifi ées grâce à ses réseaux virtuels et physiques. Son modèle repose sur la création d’une relation durable et exclusive entre ses contenus et les consommateurs. Il se structure autour de quatre branches d’activités : • Livre et Livre numérique : Lagardère Publishing • Travel Essentials, Duty Free & Fashion et Foodservice : Lagardère Travel Retail • Presse, Audiovisuel (Radio, TV, Production audiovisuelle), Digital et Régie publicitaire : Lagardère Active • Sponsoring, Contenus, Conseil, Événements, Athlètes, Stades, Spectacles, Salles et Artistes : Lagardère Sports and Entertainment 1945 : après la Libération, 1986 : reprise du contrôle 26 mars 2003 : Arnaud création par Marcel Chassagny d’Europe 1 par Hachette. Lagardère est nommé Gérant de la société Matra (Mécanique de Lagardère SCA. Aviation TRAction), spécialisée 10 février 1988 : dans le domaine militaire. privatisation de Matra. 2004 : acquisition d’une partie des actifs français et 1963 : Jean-Luc Lagardère 30 décembre 1992 : espagnols du groupe d’édition est nommé Directeur Général Vivendi Universal Publishing. après l’échec de La Cinq, de la société Matra dont les création de Matra Hachette activités se sont diversifi ées suite à la fusion-absorption 2007 : rebranding du Groupe dans l'aérospatiale et de Hachette par Matra, et autour de quatre grandes l'automobile. de Lagardère Groupe, société marques institutionnelles : faîtière de l’ensemble du Lagardère Publishing, 1974 : Sylvain Floirat confi e la Groupe qui adopte le statut Lagardère Services (devenue direction d’Europe 1 à Jean-Luc juridique de société en Lagardère Travel Retail en 2015), Lagardère. -

BA-Thesis the Emerge of a 2-Dimensional Global Society

BA-thesis Sociology The emerge of a 2-dimensional global society The exploitation of the social media, herd behaviour, moral panics and the 5th estate Muhammed Emin Kizilkaya Viðar Halldórsson January 2018 The emerge of a 2-dimensional global society The exploitation of the social media, herd behavior, moral panics and the 5th estate Muhammed Emin Kizilkaya Final project for BA-degree in Sociology Supervisor: Viðar Halldórsson 12 ECTS Faculty of Social Sciences of the University of Iceland January, 2018 2 Cohesion and fragmentation In the fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of BA in Sociology it is forbidden to copy this thesis without the author’s permission © Muhammed Emin Kizilkaya, 2018 3 Abstract We live in a 2-dimensional global society divided between the physical world and the virtual world both representing the social reality but constructed into different norms and standards, that each defines the contemporary post-modern information society that we all globally have become a part of. This thesis gives an abstract overview of the significant determination of the virtual world implying different perspectives on everything from micro to macro, from social to political, from mental to biological with the intention of broadening the attention on sudden societal transformation as a function of rapid technological processes. Excluding the virtual world when analysing the behaviour of individuals in all global societies increases the possibility of research bias as technology has become the society today. The new virtual world has become a more significant agent of change than the physical world and this new world should never be taken for granted. -

Galileu Galilei: El Naixement De La Ciència Moderna

Galileu Galilei: el naixement de la ciència moderna Victòria Rosselló Rosselló, V. (2016). Galileu Galilei: el naixement de la ciència moderna. In: Ginard, A.; Vicens, D. i Pons, G.X. (eds.). Idees que van canviar el món. Mon. Soc. Hist. Nat. Balears, 22; 53-65. SHNB - UIB. ISBN 978-84-608-9162-8. Disponible on-line a shnb.org/SHN_monografies Resum: El pensament de Galileu suposa el punt de partida de la Revolució Científica amb l’aparició d’una ciència on l’experimentació hi té un paper fonamental en contraposició a la ciència aristotèlica vigent al segle XVI. Amb el seu esforç intel·lectual, Galileu va fer trontollar l’edifici conceptual del seu temps amb el canvi d’actitud mental davant els problemes físics. La física galileana suposà una nova manera de mirar el món, que pretenia descobrir les lleis físiques que regulen els processos naturals. La nova manera d’analitzar els fenòmens de la naturalesa fou un procés que pot descriure’s com el pas de la recerca de causes a la recerca de lleis. La física aristotèlica s’ocupava del canvi (motio) i tenia com a objectiu comprendre els fenòmens de la naturalesa mitjançant l’examen de les causes. El coneixement pràctic (techne) havia estat exclòs per Aristòtil de la Filosofia Natural per considerar-lo inferior al coneixement científic (episteme). La Revolució Científica va consistir en bona mesura en la progressiva dissolució d’aquesta diferenciació i en la reconciliació del coneixement adquirit amb la pràctica amb l’obtingut mitjançant la raó. 54 Idees que van canviar el món Galileu Galilei va néixer el 15 de febrer de 1564 a Pisa i fou el primer de sis germans. -

I. a Comment Made on 31 August 1931, Quoted in Le Journal De Robert Levesque, in BAAG, XI, No

Notes I. A comment made on 31 August 1931, quoted in Le Journal de Robert Levesque, in BAAG, XI, no. 59, July 1983, p. 337. 2. Michel Raimond, La Crise du Roman, Des lendemains du Naturalisme aux annees vingt (Paris: Corti, 1966), pp. 9-84. 3. Quoted in A. Breton, Manifestes du Surrialisme (Paris: Gallimarde, Collection Idees), p. 15; cf. Gide,j/, 1068;}3, 181: August 1931. 4. Letter to Jean Schlumberger, I May 1935, in Gide, Litterature Engagee (Paris: Gallimard, 1950), p. 79. 5. Alain Goulet studies his earliest verse in 'Les premiers vers d'Andre Gide (1888-1891)', Cahiers Andre Gide, I (Paris: Gallimard, 1969), pp. 123- 49, and shows that by 1892 he had already decided that prose was his forte. 6. Gide-Valery, Correspondance (Paris: Gallimard, 1955), p. 46. 7. See sections of this diary reproduced in the edition by Claude Martin, Les Cahiers et les Poesies d'Andri Walter (Paris: Gallimard, Collection Poesie, 1986), pp. 181-218. 8. See Anny Wynchank, 'Metamorphoses dans Les Cahiers d'Andri Walter. Essai de retablissement de Ia chronologie dans Les Cahiers d'Andri Walter', BAAG, no. 63, July 1984, pp. 361-73; Pierre Lachasse, 'L'ordonnance symbolique des Cahiers d'Andri Walter', BAAG, no. 65,January 1985, pp. 23- 38. 9. 126, 127, 93; 106, 107, 79. The English translation fails to convey Walter's efforts in this direction, translating 'l'orthographie' (93) -itself a wilful distortion of l'orthographe, 'spelling' - by 'diction' (79), and blurring matters further on pp. 106-7. Walter proposes to replace continuellement by continument, and douloureusement by douleureusement, for instance, the better to convey the sensation he is seeking to circumscribe. -

Note to Users

NOTE TO USERS This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI SOME ETHICAL AND PUBLIC POLICY IMPLICATIONS OF TECHNOLOGICAL DEPENDENCY WITH REFERENCE $0 INNIS, MCLUHAN AND GRANT A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Guelph by JAMES B. GERRIE In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 1999 James B. Gerrie, 1999 National Library BibliotMque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellington OttawaON KIAON4 Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L7autewa accorde me licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive pennettant a la National Library of Canada to Bibliotheque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, preter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette these sow paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format electronique . The author retains ownership of the L'autew conserve la propriete du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protege cette these. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othemise de celle-ci ne doivent &e imprimes reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. ABSTRACT SOME ETHICAL AND PUBLIC POLICY IMPLICATIONS OF TECHNOLOGICAL DEPENDENCY WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO THE WORKS OF HAROLD ADAMS INNIS, MARSHALL MCLUHAN AND GEORGE GRANT James B. Gerrie Advisor : University of Guelph Professor J. Newman This thesis is an investigation of an alternative interpretation of certain aspects of the intellectual legacy of three influential Canadian academics: Harold Innis, Marshall McLuhan, and George Grant.