Note to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REFERENCE DOCUMENT Containing the Annual Financial Report Fiscal Year 2016 PROFILE

REFERENCE DOCUMENT containing the Annual Financial Report Fiscal Year 2016 PROFILE The Lagardère group is a global leader in content publishing, production, broadcasting and distribution, whose powerful brands leverage its virtual and physical networks to attract and enjoy qualifi ed audiences. The Group’s business model relies on creating a lasting and exclusive relationship between the content it offers and its customers. It is structured around four business divisions: • Books and e-Books: Lagardère Publishing • Travel Essentials, Duty Free & Fashion, and Foodservice: Lagardère Travel Retail • Press, Audiovisual (Radio, Television, Audiovisual Production), Digital and Advertising Sales Brokerage: Lagardère Active • Sponsorship, Content, Consulting, Events, Athletes, Stadiums, Shows, Venues and Artists: Lagardère Sports and Entertainment 1945: at the end of World 1986: Hachette regains 26 March 2003: War II, Marcel Chassagny founds control of Europe 1. Arnaud Lagardère is appointed Matra (Mécanique Aviation Managing Partner of TRAction), a company focused 10 February 1988: Lagardère SCA. on the defence industry. Matra is privatised. 2004: the Group acquires 1963: Jean-Luc Lagardère 30 December 1992: a portion of Vivendi Universal becomes Chief Executive Publishing’s French and following the failure of French Offi cer of Matra, which Spanish assets. television channel La Cinq, has diversifi ed into aerospace Hachette is merged into Matra and automobiles. to form Matra-Hachette, 2007: the Group reorganises and Lagardère Groupe, a French around four major institutional 1974: Sylvain Floirat asks partnership limited by shares, brands: Lagardère Publishing, Jean-Luc Lagardère to head is created as the umbrella Lagardère Services (which the Europe 1 radio network. company for the entire became Lagardère Travel Retail ensemble. -

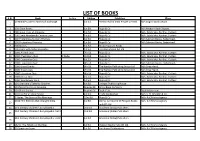

List of Books S.N

LIST OF BOOKS S.N. Book Author Edition Publisher Place 10 Minute Guide to Microsoft Exchange. 1st Ed. Prentic-Hall of India Private Limited. M/s English Book Depot 1 2 100 Great Books. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s Modern Book Depote, 3 100 Great Lives of Antiquity. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 4 100 Great Nineteenth Century Lives. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 5 100 Pretentious Nursery Rhymes. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s Sabnam Books, Badambadi, 6 100 Pretentious Proverbs. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s Sabnam Books, Badambadi, 7 100 Stories. 1st Ed. Better Yourself Books 8 100 Years with Nobel Laureates. 1st Ed. I K International Pvt Ltd 9 1000 Animal Quiz. 7th Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 10 1000 Chemistery Quiz. C Dube 3rd Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 11 1000 Economics Quiz. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 12 1000 Economics Quiz. 4th Ed. Rupa & Co M/s Sabnam Books, Badambadi, 13 1000 Great Events. 6th Ed. The Hamlyn Publishing Group Ltd. M/s Dreamland, 14 1000 Great Lives. 7th Ed. The Hamlyn Publishing Group Ltd. M/s Dreamland, 15 1000 Literature Quiz. 4th Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 16 1000 Orissa Quiz. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 17 1000 Wordpower Quiz. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 18 101 Grandma's Tales for Children. 1st Ed. Dhingra Publishing House 19 101 Moral Stories of Grandpa. -

Milestonesofmannedflight World

' J/ILESTONES of JfANNED i^LIGHT With a short dash down the runway, the machine lifted into the air and was flying. It was only a flight of twelve seconds, and it was an uncertain, waiy. creeping sort offlight at best: but it was a realflight at last and not a glide. ORV1U.E VPRK.HT A DIRECT RESULT OF OnUle Wright's intrepid 12- second A flight on Kill Devil Hill in 1903. mankind, in the space of just nine decades, has developed the means to leave the boundaries of Earth, visit space and return. As a matter of routine, even- )ear millions of business people and tourists travel to the furthest -^ reaches of our planet within a matter of hours - some at twice the speed of sound. The progress has, quite simpl) . been astonishing. Having discovered the means of controlled flight in a powered, heavier-than-air machine, other uses than those of transpon were inevitable and research into the militan- potential of manned flight began almost immediatel>-. The subsequent effect of aviation on warfare has been nothing shon of revolutionary', and in most of the years since 1903 the leading technological innovations have resulted from militan- research programs. In Milestones of Manned Flight, aviation expen Mike .Spick has selected the -iO-plus events, both civil and militan-, which he considers to mark the most significant points of aviation histon-. Each one is illustrated, and where there have been significant related developments from that particular milestone, then these are featured too. From the intrepid and pioneering Wright brothers to the high-technology' gurus developing the F-22 Advanced Tactical Fighter, the histon' of manned flight is. -

Document De Référence 2016 Lagardère

DOCUMENT DE RÉFÉRENCE contenant un Rapport fi nancier annuel Exercice 2016 PROFIL Le groupe Lagardère est un des leaders mondiaux de l’édition, la production, la diffusion et la distribution de contenus dont les marques fortes génèrent et rencontrent des audiences qualifi ées grâce à ses réseaux virtuels et physiques. Son modèle repose sur la création d’une relation durable et exclusive entre ses contenus et les consommateurs. Il se structure autour de quatre branches d’activités : • Livre et Livre numérique : Lagardère Publishing • Travel Essentials, Duty Free & Fashion et Foodservice : Lagardère Travel Retail • Presse, Audiovisuel (Radio, TV, Production audiovisuelle), Digital et Régie publicitaire : Lagardère Active • Sponsoring, Contenus, Conseil, Événements, Athlètes, Stades, Spectacles, Salles et Artistes : Lagardère Sports and Entertainment 1945 : après la Libération, 1986 : reprise du contrôle 26 mars 2003 : Arnaud création par Marcel Chassagny d’Europe 1 par Hachette. Lagardère est nommé Gérant de la société Matra (Mécanique de Lagardère SCA. Aviation TRAction), spécialisée 10 février 1988 : dans le domaine militaire. privatisation de Matra. 2004 : acquisition d’une partie des actifs français et 1963 : Jean-Luc Lagardère 30 décembre 1992 : espagnols du groupe d’édition est nommé Directeur Général Vivendi Universal Publishing. après l’échec de La Cinq, de la société Matra dont les création de Matra Hachette activités se sont diversifi ées suite à la fusion-absorption 2007 : rebranding du Groupe dans l'aérospatiale et de Hachette par Matra, et autour de quatre grandes l'automobile. de Lagardère Groupe, société marques institutionnelles : faîtière de l’ensemble du Lagardère Publishing, 1974 : Sylvain Floirat confi e la Groupe qui adopte le statut Lagardère Services (devenue direction d’Europe 1 à Jean-Luc juridique de société en Lagardère Travel Retail en 2015), Lagardère. -

BA-Thesis the Emerge of a 2-Dimensional Global Society

BA-thesis Sociology The emerge of a 2-dimensional global society The exploitation of the social media, herd behaviour, moral panics and the 5th estate Muhammed Emin Kizilkaya Viðar Halldórsson January 2018 The emerge of a 2-dimensional global society The exploitation of the social media, herd behavior, moral panics and the 5th estate Muhammed Emin Kizilkaya Final project for BA-degree in Sociology Supervisor: Viðar Halldórsson 12 ECTS Faculty of Social Sciences of the University of Iceland January, 2018 2 Cohesion and fragmentation In the fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of BA in Sociology it is forbidden to copy this thesis without the author’s permission © Muhammed Emin Kizilkaya, 2018 3 Abstract We live in a 2-dimensional global society divided between the physical world and the virtual world both representing the social reality but constructed into different norms and standards, that each defines the contemporary post-modern information society that we all globally have become a part of. This thesis gives an abstract overview of the significant determination of the virtual world implying different perspectives on everything from micro to macro, from social to political, from mental to biological with the intention of broadening the attention on sudden societal transformation as a function of rapid technological processes. Excluding the virtual world when analysing the behaviour of individuals in all global societies increases the possibility of research bias as technology has become the society today. The new virtual world has become a more significant agent of change than the physical world and this new world should never be taken for granted. -

I. a Comment Made on 31 August 1931, Quoted in Le Journal De Robert Levesque, in BAAG, XI, No

Notes I. A comment made on 31 August 1931, quoted in Le Journal de Robert Levesque, in BAAG, XI, no. 59, July 1983, p. 337. 2. Michel Raimond, La Crise du Roman, Des lendemains du Naturalisme aux annees vingt (Paris: Corti, 1966), pp. 9-84. 3. Quoted in A. Breton, Manifestes du Surrialisme (Paris: Gallimarde, Collection Idees), p. 15; cf. Gide,j/, 1068;}3, 181: August 1931. 4. Letter to Jean Schlumberger, I May 1935, in Gide, Litterature Engagee (Paris: Gallimard, 1950), p. 79. 5. Alain Goulet studies his earliest verse in 'Les premiers vers d'Andre Gide (1888-1891)', Cahiers Andre Gide, I (Paris: Gallimard, 1969), pp. 123- 49, and shows that by 1892 he had already decided that prose was his forte. 6. Gide-Valery, Correspondance (Paris: Gallimard, 1955), p. 46. 7. See sections of this diary reproduced in the edition by Claude Martin, Les Cahiers et les Poesies d'Andri Walter (Paris: Gallimard, Collection Poesie, 1986), pp. 181-218. 8. See Anny Wynchank, 'Metamorphoses dans Les Cahiers d'Andri Walter. Essai de retablissement de Ia chronologie dans Les Cahiers d'Andri Walter', BAAG, no. 63, July 1984, pp. 361-73; Pierre Lachasse, 'L'ordonnance symbolique des Cahiers d'Andri Walter', BAAG, no. 65,January 1985, pp. 23- 38. 9. 126, 127, 93; 106, 107, 79. The English translation fails to convey Walter's efforts in this direction, translating 'l'orthographie' (93) -itself a wilful distortion of l'orthographe, 'spelling' - by 'diction' (79), and blurring matters further on pp. 106-7. Walter proposes to replace continuellement by continument, and douloureusement by douleureusement, for instance, the better to convey the sensation he is seeking to circumscribe. -

Rank Downloads Q3-2017 Active Platforms Q3-2017 1 HP

Rank Brand Downloads Q3-2017 Active platforms q3-2017 Downloads y-o-y 1 HP 303,669,763 2,219 99% 2 Lenovo 177,100,074 1,734 68% 3 Philips 148,066,292 1,507 -24% 4 Apple 103,652,437 829 224% 5 Acer 100,460,511 1,578 58% 6 Samsung 82,907,164 1,997 72% 7 ASUS 82,186,318 1,690 86% 8 DELL 80,294,620 1,473 77% 9 Fujitsu 57,577,946 1,099 94% 10 Hewlett Packard Enterprise 57,079,300 787 -10% 11 Toshiba 49,415,280 1,375 41% 12 Sony 42,057,231 1,354 37% 13 Canon 27,068,023 1,553 17% 14 Panasonic 25,311,684 601 34% 15 Hama 24,236,374 394 213% 15 BTI 23,297,816 178 338% 16 3M 20,262,236 712 722% 17 Microsoft 20,018,316 639 -11% 18 Bosch 20,015,141 516 170% 19 Lexmark 19,125,788 1,067 104% 20 MSI 18,004,192 545 74% 21 IBM 17,845,288 886 39% 22 LG 16,643,142 734 89% 23 Cisco 16,487,896 520 23% 24 Intel 16,425,029 1,289 73% 25 Epson 15,675,105 629 23% 26 Xerox 15,181,934 1,030 86% 27 C2G 14,827,411 568 167% 28 Belkin 14,129,899 440 43% 29 Empire 13,633,971 128 603% 30 AGI 13,208,149 189 345% 31 QNAP 12,507,977 823 207% 32 Siemens 10,992,227 390 183% 33 Adobe 10,947,315 285 -7% 34 APC 10,816,375 1,066 54% 35 StarTech.com 10,333,843 819 102% 36 TomTom 10,253,360 759 47% 37 Brother 10,246,577 1,344 39% 38 MusicSkins 10,246,462 76 231% 39 Wentronic 9,605,067 305 254% 40 Add-On Computer Peripherals (ACP) 9,360,340 140 334% 41 Logitech 8,822,469 1,318 115% 42 AEG 8,805,496 683 -16% 43 Crocfol 8,570,601 162 268% 44 Panduit 8,567,835 163 452% 45 Zebra 8,198,502 433 72% 46 Memory Solution 8,108,528 128 290% 47 Nokia 7,927,162 402 70% 48 Kingston Technology 7,924,495 -

Media and Power

Media and Power Media and Power addresses three key questions about the relationship between media and society. How much power do the media have? Who really controls the media? What is the relationship between media and power in society? In this major new book, James Curran reviews the different answers which have been given, before advancing original interpretations in a series of ground- breaking essays. The book also provides a guided tour of major debates in media studies. What part did the media play in the making of modern society? How did ‘new media’ change society in the past? Will radical media research recover from its mid-life crisis? What are the limitations of the US-based model of ‘communications research’? Is globalization disempowering national electorates or bringing into being a new, progressive global politics? Is public service television the dying product of the nation in an age of globalization? What can be learned from the ‘third way’ tradition of European media policy? Curran’s response to these questions provides both a clear introduction to media research and an innovative analysis of media power, and is written by one of the field’s leading scholars. James Curran is Professor of Communications at Goldsmiths College, University of London. He is the editor or author of fourteen books about media, including Power Without Responsibility: The Press and Broadcasting in Britain (with Jean Seaton, 6th edition, 2002), and Mass Media and Society (edited with Michael Gurevitch, 3rd edition, 2000). COMMUNICATION AND SOCIETY -

Bill Pronzini Archive, 1967 -1986

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf929006b0 No online items Guide to the Bill Pronzini Archive, 1967 -1986 Processed by The California State Library staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Xiuzhi Zhou California History Room California State Library Library and Courts Building II 900 N. Street, Room 200 P.O. Box 942837 Sacramento, California 94237-0001 Phone: (916) 654-0176 Fax: (916) 654-8777 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ca.gov/ © 1999 California State Library. All rights reserved. Guide to the Bill Pronzini Archive, 1425 - 1521 1 1967 -1986 Guide to the Bill Pronzini Archive, 1967 -1986 California State Library Sacramento, California Contact Information: California History Room California State Library Library and Courts Building II 900 N. Street, Room 200 P.O. Box 942837 Sacramento, California 94237-0001 Phone: (916) 654-0176 Fax: (916) 654-8777 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ca.gov/ Processed by: The California State Library staff Encoded by: Xiuzhi Zhou © 1999 California State Library. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Bill Pronzini Archive, Date (inclusive): 1967 -1986 Box Number: 1425 - 1521 Creator: Pronzini, Bill Repository: California State Library Sacramento, California Language: English. Access Restricted. Conditions of Use Please credit California State Library. Publication Rights Copyright has not been assigned to California State Library. All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing. Permission for publication is given on behalf of California State Library as the owner of the physical items and is not intended to include or imply permission of the copyright holder, which must also be obtained by the reader. -

Pol 4213-40 Pensée Politique : Les Idéologies Autoritaires

Université du Québec à Montréal Département de science politique Session Hiver 2014 Pol 4213-40 Pensée politique : les idéologies autoritaires Jeudi 9h30-12h30 Enseignant : Jean-François Lessard Courriel : [email protected] Bureau : A-3690 Téléphone : 514-987-3000, poste 4141 Disponibilités : Les jeudis entre 12h30 et 13h30 ou sur rendez-vous Descriptif officiel du cours Les idéologies autoritaires aux 19e et 20e siècles: la tradition contre- révolutionnaire, les fascismes, le bolchévisme et leurs avatars. Ces idéologies seront examinées à partir d'un corpus de textes originaux et situées dans leur contexte historique respectif. On procèdera également à une évaluation des principales théories, analyses et interprétations auxquelles elles ont donné lieu (théories du totalitarisme, théories marxistes, sociologiques ou psychosociologiques du fascisme, etc.). On présentera enfin quelques débats récents suscités par l'évaluation des expériences autoritaires du 20e siècle et de leur héritage (ceux relatifs au problème du révisionnisme historique, au potentiel autoritaire des formes actuelles de populisme, de nationalisme et de fondamentalisme, etc.). ____________________________ Objectifs de formation Ce cours a pour but d’éclairer les étudiants sur l’une des périodes les plus troublées de l’histoire de l’humanité : les totalitarismes et les régimes autoritaires qui ont marqué le 20e siècle. Nous sommes les héritiers de cette période, c’est pourquoi un effort de compréhension est nécessaire afin de pouvoir mieux comprendre l’évolution actuelle des sociétés contemporaines. 2 Ce cours porte essentiellement sur la pensée politique. Il ne s’agira donc pas de s’attarder de manière indue sur les « faits ». Nous nous concentrerons plutôt sur les « idées ». Les études portant sur le nazisme, les fascismes et les totalitarismes sont nombreuses et variées. -

Exhibition List Jack Sharkey, the Secret Martians

MARCH-JUNE 2012 35c cabinet 14: ace double back sf cabinet 18 (large): non-fiction and omnibus sf Poul Anderson, Un-Man and Other Novellas. New York: Ace Life in the Twenty-First Century. Edited by M. Vassiliev and S. Books, 1962 Gouschev. London: Souvenir Press, 1960 Charles L. Fontenay, Rebels of the Red Planet. New York: Ace Murray Leinster, ‘First Contact’ in Stories for Tomorrow. Books, 1961 Selections and prefaces by William Sloane. London: Eyre & Gordon R. Dickson, Delusion World. New York: Ace Books, 1961 Spottiswoode, 1955 ___, Spacial Delivery. New York: Ace Books, 1961 I.M. Levitt, A Space Traveller’s Guide to Mars. London: Victor Margaret St. Clair, The Green Queen. New York: Ace Books, 1956 Gollancz, 1957 ____, The Games of Neith. New York: Ace Books, 1960 Men Against the Stars. Edited by Martin Greenberg. London: The Fred Fastier Science Fiction Collection Ray Cummings, Wandl the Invader. New York: Ace Books, 1961 Grayson & Grayson, 1951 Fritz Leiber, The Big Time. New York: Ace Books, 1961 Martin Caidin, Worlds in Space. London: Sidgwick and Poul Anderson, War of the Wing-Men. New York: Ace Books, 1958 Jackson, 1954 G. McDonald Wallis, The Light of Lilith. New York: Ace Patrick Moore, Science and Fiction. London: George G. Harrap Books, 1961 & Co., 1957 Exhibition List Jack Sharkey, The Secret Martians. New York: Ace Books, [1960] Aldous Huxley, Brave New World Revisited. London: Chatto & Eric Frank Russell, The Space Willies. New York: Ace Books, 1958 Windus, 1959 Robert A. W. Lowndes, The Puzzle Planet. New York: Ace J. B. Rhine, The Reach of the Mind. -

Adorno's Practical Philosophy

more information – www.cambridge.org/9781107036543 ADORNO’S PRACTICAL PHILOSOPHY Adorno notoriously asserted that there is no ‘right’ life in our current social world. This assertion has contributed to the widespread perception that his philosophy has no practical import or coherent ethics, and he is often accused of being too negative. Fabian Freyenhagen reconstructs and defends Adorno’s practical philosophy in response to these charges. He argues that Adorno’s deep pessimism about the contemporary social world is coupled with a strong optimism about human potential, and that this optimism explains his negative views about the social world, and his demand that we resist and change it. He shows that Adorno holds a substantive ethics, albeit one that is minimalist and based on a pluralist conception of the bad – a guide for living less wrongly. His incisive study does much to advance our understanding of Adorno, and is also an important intervention in current debates in moral philosophy. fabian freyenhagen is Reader in Philosophy at the University of Essex. He is co-editor (with Thom Brooks) of The Legacy of John Rawls (2005), and (with Gordon Finlayson) of Disputing the Political: Habermas and Rawls (2011). He has published in journals including Kantian Review, Inquiry, Telos, and Politics, Philosophy & Economics. MODERN EUROPEAN PHILOSOPHY General Editor WAYNE MARTIN,University of Essex Advisory Board SEBASTIAN GARDNER,University College London BEATRICE HAN-PILE,University of Essex HANS SLUGA,University of California, Berkeley Some recent