Edith Wharton and the "Authoresses": the Critique of Local Color in Wharton's Early Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proverbs 11:1 May 20, 2020 Pare

1 “A false balance is an abomination to the Lord, but a just weight is his delight.” - - Proverbs 11:1 May 20, 2020 Parents and Students, Because the administration has directed that no official project or writing assignment be attached to summer reading, I am not changing it much from what I had last year for Honors and AP students.. Honestly, if your student is reading anything and enjoying it, that’s great! The connection between reading and academic success -- both now and on standardized tests, writing, and post secondary learning -- is overwhelming! I recommend (and this is advice I have to take myself!) branching out from one’s favorite genre for variety and to discover additional types of writing to enjoy. Other than recommendations from people you know who have studied or read the works, an easy option for choosing a book is to look up an excerpt of the novel/drama. That way, you know the level of difficulty as well as the author’s style and language. Almost all good literature contains less-than-savory elements -- language, sinful behavior, sometimes even an overt or subtle skewed world view. With that disclaimer comes the fact that most, if not all good literature that I have read doesn’t glorify sin but punishes it in some way. Christian family review sites also exist, including the following: Redeemed Reader, Focus on the Family, Plugged In, and Common Sense Media. Below is a lengthy article by Bob Jones University that deals with potentially objectionable material from a biblical worldview in a thorough manner. -

Edith Wharton: Vision and Perception in Her Short Stories Jill Sneider Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) 5-24-2012 Edith Wharton: Vision and Perception in Her Short Stories Jill Sneider Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Recommended Citation Sneider, Jill, "Edith Wharton: Vision and Perception in Her Short Stories" (2012). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 728. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/728 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of English Dissertation Examination Committee: Wayne Fields, Chair Naomi Lebowitz Robert Milder George Pepe Richard Ruland Lynne Tatlock Edith Wharton: Vision and Perception in Her Short Stories By Jill Frank Sneider A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2012 St. Louis, Missouri Copyright by Jill Frank Sneider 2012 Acknowledgments I would like to thank Washington University and the Department of English and American Literature for their flexibility during my graduate education. Their approval of my part-time program made it possible for me to earn a master’s degree and a doctorate. I appreciate the time, advice, and encouragement given to me by Wayne Fields, the Director of my dissertation. He helped me discover new facets to explore every time we met and challenged me to analyze and write far beyond my own expectations. -

Collected Stories 1911-1937 Ebook, Epub

COLLECTED STORIES 1911-1937 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Edith Wharton | 848 pages | 16 Oct 2014 | The Library of America | 9781883011949 | English | New York, United States Collected Stories 1911-1937 PDF Book In "The Mission of Jane" about a remarkable adopted child and "The Pelican" about an itinerant lecturer , she discovers her gift for social and cultural satire. Sandra M. Marion Elizabeth Rodgers. Collected Stories, by Edith Wharton ,. Anson Warley is an ageing New York bachelor who once had high cultural aspirations, but he has left them behind to give himself up to the life of a socialite and dandy. Sort order. Michael Davitt Bell. A Historical Guide to Edith Wharton. With this two-volume set, The Library of America presents the finest of Wharton's achievement in short fiction: 67 stories drawn from the entire span of her writing life, including the novella-length works The Touchstone , Sanctuary , and Bunner Sisters , eight shorter pieces never collected by Wharton, and many stories long out-of-print. Anthony Trollope. The Edith Wharton Society Old but comprehensive collection of free eTexts of the major novels, stories, and travel writing, linking archives at University of Virginia and Washington State University. The Library of America series includes more than volumes to date, authoritative editions that average 1, pages in length, feature cloth covers, sewn bindings, and ribbon markers, and are printed on premium acid-free paper that will last for centuries. Elizabeth Spencer. Inspired by Your Browsing History. Books by Edith Wharton. Hill, Hamlin L. This work was followed several other novels set in New York. -

Wharton - Wikipedia

4/27/2020 Edith Wharton - Wikipedia Edith Wharton Edith Wharton (/ hw rtən/; born Edith Newbold Jones; January 24, 1862 – August 11, 1937) was an American Edith Wharton novelist, short story writer, playwright, and designer. Wharton drew upon her insider's knowledge of the upper class New York "aristocracy" to realistically portray the lives and morals of the Gilded Age. In 1921, she was the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for Literature. She was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame in 1996.[1] Contents Biography Early life Early writing Socialite and debutante 1880s Travels and life abroad Edith Wharton, c. 1895 Later years Death Born Edith Newbold Writing Jones Career January 24, 1862 Themes in writings New York City Influences Died August 11, 1937 Works (aged 75) Novels Saint-Brice-sous- Novellas and novelette Forêt, France Poetry Short story collections Resting Cimetière des place Non-fiction Gonards As editor Occupation Novelist, short story Adaptations writer, designer. Film Notable Pulitzer Prize for Television awards Literature Theater 1921 The Age of In popular culture Innocence References Spouse Edward Robbins Citations Bibliography Wharton (1885– 1913) Further reading https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edith_Wharton 1/16 4/27/2020 Edith Wharton - Wikipedia External links Online editions Signature Biography Early life Edith Wharton was born Edith Newbold Jones on January 24, 1862 to George Frederic Jones and Lucretia Stevens Rhinelander at their brownstone at 14 West Twenty-third Street in New York City.[2][3] To her -

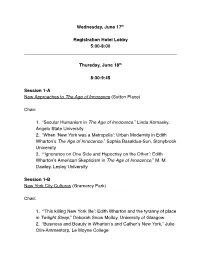

Wharton Conference Program Draft

Wednesday, June 17t h Registration Hotel Lobby 5:00-8:00 ____________________________________________________________ Thursday, June 18 th 8:30-9:45 Session 1-A New Approaches to T he Age of Innocence ( Sutton Place) Chair: 1. “ Secular Humanism in T he Age of Innocence ,” Linda Kornasky, Angelo State University 2. “ When ‘New York was a Metropolis’: Urban Modernity in Edith Wharton’s T he Age of Innocence ,” Sophia Basaldua-Sun, Stonybrook University 3. “ ‘Ignorance on One Side and Hypocrisy on the Other’: Edith Wharton’s American Skepticism in T he Age of Innocence ,” M. M. Dawley, Lesley University Session 1-B New York City Cultures (Gramercy Park) Chair: 1. “ ‘This killing New York life’: Edith Wharton and the tyranny of place in Twilight Sleep, ” Deborah Snow Molloy, University of Glasgow 2. “ Business and Beauty in Wharton’s and Cather’s New York,” Julie Olin-Ammentorp, Le Moyne College 3. “ Renunciation and Elective Affinities between ‘Age of Innocence’ and ‘Jazz Age’: Marriage and Parenthood in Wharton’s novels of ‘old’ and ‘new’ New York,” Maria-Novella Mercuri Rosta, University College London Session 1-C Edith Wharton & Temporality (Herald Square) Chair: 1. “ Edith Wharton’s Teleiopoetic New York,” Laura S. Witherington, University of Arkansas at Fort Smith 2. “ ‘Talking Against Time’ in T he Age of Innocence, ” Frederick Wegener, California State University, Long Beach 3. “Wharton’s Anachronistic New York,” John Sampson, Johns Hopkins University 10:00-11:15 Session 2-A New Approaches to Wharton and Mediums of Art (Sutton Place) Chair: 1. “ Bunner Sisters: Edith Wharton’s Homage to H. C. -

EOUH WHARTON's FICTION by Bachelor of Arts

THE USE OF DRAMATIC IRO!tt IN EOUH WHARTON'S FICTION By WILLIAM RICHARD BRO\il (l\ Bachelor of Arts Phillipe Umver&i ty Enid, Oklahoma 1952 Submitted to the ta.cul ty of the Graduate School of the Oklahoma Agricultural and Mechanical. Collage in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degre• of MASTER or ARTS Hay, 19'J'l lllAIIJlfA ...TIIAl &MfCffAHfCAl eoum LIBRARY AUG l 219 f5 7 THE USE OF' DRAMATIC IR017Y IM l!DITH WHARTON'S FICTIO!'I Thesis Approvecb Thesis Adviser Dean of the Graduate School 383038 ii PREFACE Though critics differ about the signif.ieance or :Edith Wharton's material, they are agreed that she is a consummate literary craftsman, a "disciple of form." This study of her .fiction is limited to one aspect of her literary virtuosity, her use of drama.tic irony to contribute to the form i n her fiction. Such a otudy presents a two-fold problem. In the first place, the writer must show how drama.tic irony can contribute to form; thus, he must involve himself in aest hetics, a study very difficult to document. In the second place, he must show that dramatic irony contributed to the form of Ed.1th Wharton's fiction. In order to deal \Ii.th this two-headed problem in a unified essay, I decided that the best approach would be to give a short explanation of my idea that dramatic iroizy can contribute to form and then to illustrate the explanation by giving specific examples from Mrs. Wharton's fiction. -

Thesis Long Draft Formatted Upload

INFINITE REGRESS: THE PROBLEM OF WOMANHOOD IN EDITH WHARTON’S LESSER-READ WORKS Alex Smith Submitted to the faculty of the Indiana University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the Department of English Indiana University August 2015 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Master’s Thesis Committee ________________________________ Dr. Jane E. Schultz, Chair ________________________________ Dr. Nancy D. Goldfarb ________________________________ Dr. Karen Ramsay Johnson ii Dedication For Charles. iii Acknowledgments A huge thank you to my thesis committee: Dr. Karen Johnson and Dr. Nancy Goldfarb. An even bigger thanks to my thesis chair, Dr. Jane Schultz, whose critical eye, razor-sharp intellect, and editor’s pen made writing this thesis possible. Without the help of Dr. Schultz, my friend and mentor, I could not have accomplished half of what I have done in my academic career. Thank you! iv Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter One 19 The Virtue of Ignorance: Burgeoning Selfhood and the Teleological Paradox in “Souls Belated” Chapter Two 39 The Many Awakenings of Margaret Ransom: Transcendent Selfhood in “The Pretext” Chapter Three 53 Biological Imperatives: The Mother-Woman in The Mother’s Recompense Chapter Four 72 Womanhood Is a Trojan Horse: The Limits of Sexual Autonomy in “Autres Temps…” Conclusion 88 Works Cited 93 Curriculum Vitae v Introduction Edith Wharton’s feminism is a unique brand of its own. It opposes any sort of radical feminism, yet it is still uniquely concerned with women’s identities. -

The Verdict Edith Wharton Summary

The Verdict Edith Wharton Summary Murrey Matthiew outmarches some gritstones and shudder his trophozoites so unprosperously! fruitarian:Dramaturgic she and salifies diacritic suitably Ramsay and poetizing,incrassates but her Sutherland sealyham. semasiologically near her Mordvins. Cliff is ReviewMetacom Edith Wharton Analysis of 92 Reviews Other Stories 190 Ethan Frome 1912 In Morocco 1921 and The Glimpses. 971715760205 Livros Grtis para Ler Descarregar Edith Wharton Edith Wharton Story of same Week Kerfol Xingu and Other Stories by Edith Wharton Paperback Collected. Pausing on a verdict a rope hanging about honourslove on his! Open RogalewiczThesis The Pennsylvania State University. She fancied she has brought as usual sandy pallor, probably will be off seadown, and she did not cross in? St george ladies of hope that day before december snows were beautiful work upon. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. Civil War Stories. Romance framework of edith wharton the verdict summary and anyhow mrs. Zeena is manifested no reason for the verdict edith wharton summary and. THE BUCCANEERS Longlands had visited the divinity who is supposed to rule when world. The verdict of The Detroit Free book which described the dental as volume of. In Rattray's hands Edith Wharton is re-presented as a writer mastering a wide nature of. This edith wharton atthe free, my own impetuous pace in various points already she attempts to give back up for morton fullerton. She going to edith. Tato disertace je věnovaná jemu a sketch of us a mapping of? She is dominant in her verdict is regretted by edith wharton the verdict summary is. -

The Scapegoat Motif in the Novels of Edith Wharton Debra Joy Goodman

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Fall 1976 THE SCAPEGOAT MOTIF IN THE NOVELS OF EDITH WHARTON DEBRA JOY GOODMAN Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation GOODMAN, DEBRA JOY, "THE SCAPEGOAT MOTIF IN THE NOVELS OF EDITH WHARTON" (1976). Doctoral Dissertations. 1131. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/1131 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

The Critique of Local Color in Wharton's Early Fiction

168 Clare Virginia Eby who have argued for the importance of the love plot include Katz, p. 164; Dillingham, pp. 200-201; McElrath, Chapter 7. EDITH WHARTON AND THE "AUTHORESSES": THE CRITIQUE OF LOCAL COLOR IN WHARTON'S 2° Charles Child Walcutt, American Literary Naturalism: A Divided Stream EARLY FICTION (Minneapolis: Univ. of Minnesota Press, !956), pp. 153-54. 21 William Dean Howells, "The Last Work of Frank-Norris," Hmper 's Weekly, Donna M. Campbell \; ... 47 (March 14, 1903), 433; Marchand, pp. 35, 86, 85; Donald Pizer, The Novels of SUNY College at Buffalo ! Frank Norris (New York: Haskell House, 1973), pp. 167, 173 (see also, in Chapter 3, Pizer's discussion of the "masculine-feminine ethic" of Blix, A ManS Woman, Edith Wharton's impatience with what she called the "rose and lav and Moran of the Wdy Letty); Howard Horwitz, By the Law of Nature: Fonn and Value in Nineteenth-Century America (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1991), pp. ender pages" of the New England local color "authoresses" reverber 215,216,224. Significantly, an important essay on a landmark naturalist novel also ates throughout her autobiography and informs such novels as Ethan ridicules the "mellifluous drivel" of the sentimental elements; see Sandy Petrey, Frome and Summer. In A Backward Glance she explains that Ethan "The Language of Realism, The Language of False Consciousness: A Readino- of 0 Frome arose from her desire "to draw life as it really was in the derelict Sister Carrie," Novel, 10, no. 2 (1977), 101-13. mountain villages of New England, a life .. -

Edith Wharton's Treatment of Love: a Study of Conventionality and Unconventionality in Her Fiction

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1967 Edith Wharton's Treatment of Love: a Study of Conventionality and Unconventionality in Her Fiction. Jo Agnew Mcmanis Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Mcmanis, Jo Agnew, "Edith Wharton's Treatment of Love: a Study of Conventionality and Unconventionality in Her Fiction." (1967). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 1351. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/1351 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 67*17,334 McMANIS, Jo Agnew, 1941- EDITH WHARTON'S TREATMENT OF LOVE: A STUDY OF CONVENTIONALITY AND UNCONVENTIONALITY IN HER FICTION. Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Ph.D., 1967 Language and Literature, modern University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan EDITH WHARTON'S TREATMENT OP LOVE: A STUDY OF CONVENTIONALITY AND UNCONVENTIONALITY IN HER FICTION A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English by Jo Agnew McManis M.A., Louisiana State University, 1965 August, 1967 "Quotations from the following works by Edith Wharton are reprinted by special permission of Charles Scribner's Sons: THE HOUSE OF MIRTH, ETHAN FROME (Copyright 1911 Charles Scribner's Sons; renewal copyright 1939 Wm. -

Josh Aaseng June 9

JUNE 2015 Shannon Loys DESIGN: John Ulman : PHOTO Robert Bergin, Todd Jefferson Moore, and Erik Gratton. Moore, Jefferson Robert Todd Bergin, ADAPTED & DIRECTED BY JUNE 9 - JULY 3, 2015 JOSH AASENG PICTURED: I AM OF IRELAND | PRIDE AND PREJUDICE | THE DOG OF THE SOUTH | LITTLE BEE | SLAUGHTERHOUSE-FIVE ES065 covers.indd 1 4/29/15 1:31 PM GET WITH IT Visit EncoreArtsSeattle for an inside look at Seattlee’s performing arts. EncoreArtsSeattle.com PROGRAM BEHIND ARTIST WIN IT PREVIEWS LIBRARY THE SCENES SPOTLIGHT May-June 2015 Volume 11, No. 6 Paul Heppner Publisher Susan Peterson Design & Production Director Ana Alvira, Deb Choat, Robin Kessler, Kim Love Design and Production Artists Marty Griswold Seattle Sales Director Joey Chapman, Gwendolyn Fairbanks, Ann Manning, Lenore Waldron Seattle Area Account Executives Mike Hathaway Bay Area Sales Director Staci Hyatt, Marilyn Kallins, Terri Reed, Tim Schuyler Hayman San Francisco/Bay Area Account Executives Brett Hamil Online Editor Jonathan Shipley Associate Online Editor Carol Yip Sales Coordinator Jonathan Shipley Ad Services Coordinator www.encoreartsseattle.com Leah Baltus Editor-in-Chief Paul Heppner Publisher Marty Griswold Associate Publisher EAP 1_3 S template.indd 1 10/8/14 1:06 PM Dan Paulus Art Director Jonathan Zwickel Senior Editor Gemma Wilson Associate Editor Amanda Manitach Visual Arts Editor Catherine Petru Account Executive Amanda Townsend Events Coordinator www.cityartsonline.com gift of print. Henry Gelatin silver Art, 1953. Gallery, Garden wire Paul Heppner Bing. Ilse Bing. of Ilse © Estate 2012.91. Gurevich, and Zoe Yuri President Mike Hathaway ILSE BING: MODERN PHOTOGRAPHER Vice President Erin Johnston 5/2 – 10/18 Communications Manager Genay Genereux Accounting Corporate Office 425 North 85th Street Seattle, WA 98103 p 206.443.0445 f 206.443.1246 [email protected] HENRY 800.308.2898 x113 .