ODUMUNC 2015 the Powhatan Chiefdom: 1606

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proposed Finding

This page is intentionally left blank. Pamunkey Indian Tribe (Petitioner #323) Proposed Finding Proposed Finding The Pamunkey Indian Tribe (Petitioner #323) TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................... ii INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................................1 Regulatory Procedures .............................................................................................1 Administrative History.............................................................................................2 The Historical Indian Tribe ......................................................................................4 CONCLUSIONS UNDER THE CRITERIA (25 CFR 83.7) ..............................................9 Criterion 83.7(a) .....................................................................................................11 Criterion 83.7(b) ....................................................................................................21 Criterion 83.7(c) .....................................................................................................57 Criterion 83.7(d) ...................................................................................................81 Criterion 83.7(e) ....................................................................................................87 Criterion 83.7(f) ...................................................................................................107 -

The Indigenous Constitutional System in a Changing South Africa Digby S Koyana Adjunct Professor, Nelson R Mandela School of Law, University of Fort Hare

The Indigenous Constitutional System in a Changing South Africa Digby S Koyana Adjunct Professor, Nelson R Mandela School of Law, University of Fort Hare 1. MAIN FEATURES OF THE INDIGENOUS CONSTITUTIONAL SYSTEM In the African scenario the state comprises a hierarchy of component jural communities1. In hierarchical order, from the most comprehensive to the smallest, the jural communities are: the empire, the federation of tribes, the tribe, the district or section and the ward. The most common and simplest structure found amongst many peoples was the tribe, which consisted of a number of wards. The comprehensive jural community could be enlarged by the addition of tribes or tribal segments through conquest or voluntary subjugation. It is this way that empires, such as that of Shaka in Natal, were founded2. In such cases, the supreme figure of authority would be the king, and those at the head of the tribes, the chiefs, would be accountable to him. Junior chiefs in charge of wards would in turn be accountable to the chief, and there would naturally be yet more junior “officials”, relatives of the chief of the tribe, who would be in charge of the wards. The tribe itself has been described as “a community or collection of Natives forming a political and social organisation under the government, control and leadership of a chief who is the centre of the national or tribal life”3. The next question relates to the position of the chief as ruler in indigenous constitutional law. In principle the ruler was always a man. There are exceptions such as among the Lobedu tribe, where the ruler has regularly been a woman since 18004. -

What Happened Till the First Supply

W H A T H A P P E N E D T I L L T H E F I R S T S U P P L Y from T H E G E N E R A L H I S T O R Y O F V I R G I N I A 1 6 0 7 – 1 6 1 4 ––––––––––––––––––––––––– John Smith –––––––––––––––––––––––– In May 1607, three boatloads of English settlers sponsored by the Virginia Company of London anchored near the swampy shores of Chesapeake Bay. Among these 104 men and boys were aristocrats and craftspeople, but few farmers or others with skills crucial to survive in the wilderness. Captain John Smith, a leader among these earliest Jamestown settlers, held an interest in the London Company. Smith was an aggressive self-promoter who wrote and published a history of the Virginia colony in 1624. T H I N K T H R O U G H H I S T O R Y : Distinguishing Fact from Opinion At what points does Smith rely on facts, and at what points does he appear to offer more opinion than fact? Does this evaluation affect the value of this text as a historical document? Why or why not? –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– [June 1607–January 1608] Being thus left to our fortunes, it fortuned that within ten days scarce ten amongst us could either go or well stand, such extreme weakness and sickness oppressed us. And thereat none need marvel, if they consider the cause and reason, which was this. Whilst the trading ships stayed, our allowance was somewhat bettered by a daily proportion of biscuit, which the sailors would pilfer to sell, give, or exchange with us for money, sassafras, furs, or love. -

The Legacy of Inkosi Albert John Luthuli's Christian-Centred Political

Faith and politics in the context of struggle: the legacy of Inkosi Albert John Luthuli’s Christian-centred political leadership Simangaliso Kumalo Ministry, Education & Governance Programme, School of Religion and Theology, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa Abstract Albert John Mvumbi Luthuli, a Zulu Inkosi and former President-General of the African National Congress (ANC) and a lay-preacher in the United Congregational Church of Southern Africa (UCCSA) is a significant figure as he represents the last generation of ANC presidents who were opposed to violence in their execution of the struggle against apartheid in South Africa. He attributed his opposition to violence to his Christian faith and theology. As a result he is remembered as a peace-maker, a reputation that earned him the honour of being the first African to win the Nobel Peace Prize. Also central to Luthuli’s leadership of the ANC and his people at Groutville was democratic values of leadership where the voices of people mattered including those of the youth and women and his teaching on non-violence, much of which is shaped by his Christian faith and theology. This article seeks to examine Luthuli’s legacy as a leader who used peaceful means not only to resist apartheid but also to execute his duties both in the party and the community. The study is a contribution to the struggle of maintaining peace in the political sphere in South Africa which is marked by inter and intra party violence. The aim is to examine Luthuli’s legacy for lessons that can be used in a democratic South Africa. -

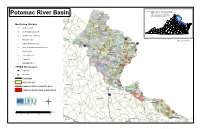

Potomac River Basin Assessment Overview

Sources: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality PL01 Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation Virginia Department of Transportation Potomac River Basin Virginia Geographic Information Network PL03 PL04 United States Geological Survey PL05 Winchester PL02 Monitoring Stations PL12 Clarke PL16 Ambient (120) Frederick Loudoun PL15 PL11 PL20 Ambient/Biological (60) PL19 PL14 PL23 PL08 PL21 Ambient/Fish Tissue (4) PL10 PL18 PL17 *# 495 Biological (20) Warren PL07 PL13 PL22 ¨¦§ PL09 PL24 draft; clb 060320 PL06 PL42 Falls ChurchArlington jk Citizen Monitoring (35) PL45 395 PL25 ¨¦§ 66 k ¨¦§ PL43 Other Non-Agency Monitoring (14) PL31 PL30 PL26 Alexandria PL44 PL46 WX Federal (23) PL32 Manassas Park Fairfax PL35 PL34 Manassas PL29 PL27 PL28 Fish Tissue (15) Fauquier PL47 PL33 PL41 ^ Trend (47) Rappahannock PL36 Prince William PL48 PL38 ! PL49 A VDH-BEACH (1) PL40 PL37 PL51 PL50 VPDES Dischargers PL52 PL39 @A PL53 Industrial PL55 PL56 @A Municipal Culpeper PL54 PL57 Interstate PL59 Stafford PL58 Watersheds PL63 Madison PL60 Impaired Rivers and Streams PL62 PL61 Fredericksburg PL64 Impaired Reservoirs or Estuaries King George PL65 Orange 95 ¨¦§ PL66 Spotsylvania PL67 PL74 PL69 Westmoreland PL70 « Albemarle PL68 Caroline PL71 Miles Louisa Essex 0 5 10 20 30 Richmond PL72 PL73 Northumberland Hanover King and Queen Fluvanna Goochland King William Frederick Clarke Sources: Virginia Department of Environmental Quality Loudoun Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation Virginia Department of Transportation Rappahannock River Basin -

EPA Interim Evaluation of Virginia's 2016-2017 Milestones

Interim Evaluation of Virginia’s 2016-2017 Milestones Progress June 30, 2017 EPA INTERIM EVALUATION OF VIRGINIA’s 2016-2017 MILESTONES As part of its role in the accountability framework, described in the Chesapeake Bay Total Maximum Daily Load (Bay TMDL) for nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is providing this interim evaluation of Virginia’s progress toward meeting its statewide and sector-specific two-year milestones for the 2016-2017 milestone period. In 2018, EPA will evaluate whether each Bay jurisdiction achieved the Chesapeake Bay Program (CBP) partnership goal of practices in place by 2017 that would achieve 60 percent of the nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment reductions necessary to achieve applicable water quality standards in the Bay compared to 2009. Load Reduction Review When evaluating 2016-2017 milestone implementation, EPA is comparing progress to expected pollutant reduction targets to assess whether statewide and sector load reductions are on track to have practices in place by 2017 that will achieve 60 percent of necessary reductions compared to 2009. This is important to understand sector progress as jurisdictions develop the Phase III Watershed Implementation Plans (WIP). Loads in this evaluation are simulated using version 5.3.2 of the CBP partnership Watershed Model and wastewater discharge data reported by the Bay jurisdictions. According to the data provided by Virginia for the 2016 progress run, Virginia is on track to achieve its statewide 2017 targets for nitrogen and phosphorus but is off track to meet its statewide targets for sediment. The data also show that, at the sector scale, Virginia is off track to meet its 2017 targets for nitrogen reductions in the Agriculture, Urban/Suburban Stormwater and Septic sectors and is also off track for phosphorus in the Urban/Suburban Stormwater sector, and off track for sediment in the Agriculture and Urban/Suburban Stormwater sectors. -

Living with the Indians.Rtf

Living With the Indians Introduction Archaeologists believe the American Indians were the first people to arrive in North America, perhaps having migrated from Asia more than 16,000 years ago. During this Paleo time period, these Indians rapidly spread throughout America and were the first people to live in Virginia. During the Woodland period, which began around 1200 B.C., Indian culture reached its highest level of complexity. By the late 16th century, Indian people in Coastal Plain Virginia, united under the leadership of Wahunsonacock, had organized themselves into approximately 32 tribes. Wahunsonacock was the paramount or supreme chief, having held the title “Powhatan.” Not a personal name, the Powhatan title was used by English settlers to identify both the leader of the tribes and the people of the paramount chiefdom he ruled. Although the Powhatan people lived in separate towns and tribes, each led by its own chief, their language, social structure, religious beliefs and cultural traditions were shared. By the time the first English settlers set foot in “Tsenacommacah, or “densely inhabited land,” the Powhatan Indians had developed a complex culture with a centralized political system. Living With the Indians is a story of the Powhatan people who lived in early 17th-century Virginia—their social, political, economic structures and everyday life ways. It is the story of individuals, cultural interactions, events and consequences that frequently challenged the survival of the Powhatan people. It is the story of how a unique culture, through strong kinship networks and tradition, has endured and maintained tribal identities in Virginia right up to the present day. -

American Indians of the Chesapeake Bay: an Introduction

AMERICAN INDIANS OF THE CHESAPEAKE BAY: AN INTRODUCTION hen Captain John Smith sailed up the Chesapeake Bay in 1608, American Indians had W already lived in the area for thousands of years. The people lived off the land by harvesting the natural resources the Bay had to offer. In the spring, thousands of shad, herring and rockfish were netted as they entered the Chesapeake’s rivers and streams to spawn. Summer months were spent tending gardens that produced corn, beans and squash. In the fall, nuts such as acorns, chestnuts and walnuts were gathered from the forest floor. Oysters and clams provided another source of food and were easily gathered from the water at low tide. Hunting parties were sent overland in search of deer, bear, wild turkey and other land animals. Nearby marshes provided wild rice and tuckahoe (arrow arum), which produced a potato-like root. With so much food available, the American Indians of the Chesapeake region were able to thrive. Indian towns were found close to the water’s edge near freshwater springs or streams. Homes were made out of bent saplings (young, Captain John Smith and his exploring party encounter two Indian men green trees) that were tied into a spearing fish in the shallows on the lower Eastern Shore. The Indians framework and covered with woven later led Smith to the village of Accomack, where he met with the chief. mats, tree bark, or animal skins. Villages often had many homes clustered together, and some were built within a palisade, a tall wall built with sturdy sticks and covered with bark, for defense. -

The Adventures of Captain John Smith, Pocahontas, and a Sundial Sara J

The Adventures of Captain John Smith, Pocahontas, and a Sundial Sara J. Schechner (Cambridge MA) Let me tell you a tale of intrigue and ingenuity, savagery and foreign shores, sex and scientific instruments. No, it is not “Desperate Housewives,” or “CSI,” but the “Adventures of Captain John Smith, Pocahontas, and a Sundial.”1 As our story opens in 1607, we find Captain John Smith paddling upstream through the Virginia wilderness, when he is ambushed by Indians, held prisoner, and repeatedly threatened with death. His life is spared first by the intervention of his magnetic compass, whose spinning needle fascinates his captors, and then by Pocahontas, the chief’s sexy daughter. At least that is how recent movies and popular writing tell the story.2 But in fact the most famous compass in American history was more than a compass – it was a pocket sundial – and the Indian princess was no seductress, but a mere child of nine or ten years, playing her part in a shaming ritual. So let us look again at the legend, as told by John Smith himself, in order to understand what his instrument meant to him. Who was John Smith?3 When Smith (1580-1631) arrived on American shores at the age of twenty-seven, he was a seasoned adventurer who had served Lord Willoughby in Europe, had sailed the Mediterranean in a merchant vessel, and had fought for the Dutch against Spain and the Austrians against the Turks. In Transylvania, he had been captured and sold as a slave to a Turk. The Turk had sent Smith as a gift to his girlfriend in Istanbul, but Smith escaped and fled through Russia and Poland. -

Tax Administration and Representative Authority in the Chiefdoms of Sierra Leone1

Tax Administration and Representative Authority in the Chiefdoms of Sierra Leone1 Richard Fanthorpe September 2004 Department of Anthropology University of Sussex 1 This report is an output of DFID/SSR research project R8095. It must not be cited or reproduced in any format without the author’s permission Contents Introduction and Methodology…………………………………………………..1 Section 1: The Development of Chiefdom Administration……………………..7 Tax Administration………………………………………………………………...7 Representative Authority………………………………………………………….15 Section 2: Survey Data……………………………………………………………23 Chiefdom Staff Working Conditions………………………………………………23 Local Tax Administration: The Current Situation………………………………..32 Calculating Chiefdom Councillorships……………………………………………45 Conclusions…………………………………………………………………………50 2 Abstract This report analyses survey data, collected by the author between March and June 2003, from five chiefdoms in Sierra Leone. The aim of the survey was to investigate the capacity of chiefdom administrations to assess and collect local tax and the relationships between taxation, political representation, and citizenship at the chiefdom level. The first section of the report explores the legal and technical development of financial administration and representative authority in the chiefdoms, with particular attention to the policy assumptions that underlay it. The second section analyses the survey data, which were collected before the new decentralised local government structures were put in place. They indicate that chiefdom financial administration is barely functional and suffers greatly from poor staff working conditions and lack of transparency and accountability among district level administrations. The rural public have little confidence in the local tax system and are unlikely to cooperate with it any further until tangible benefits from local tax revenue begin to flow in their direction. However, tax assessment (if not payment) also has a political purpose and evidence was found of manipulation of tax assessment rolls in order to yield extra chiefdom councillors. -

Where Have All the Indians Gone? Native American Eastern Seaboard Dispersal, Genealogy and DNA in Relation to Sir Walter Raleigh’S Lost Colony of Roanoke

Where Have All the Indians Gone? Native American Eastern Seaboard Dispersal, Genealogy and DNA in Relation to Sir Walter Raleigh’s Lost Colony of Roanoke. Roberta Estes Copyright 2009, all rights reserved, submitted for publication [email protected] or [email protected] Abstract Within genealogy circles, family stories of Native American1 heritage exist in many families whose American ancestry is rooted in Colonial America and traverses Appalachia. The task of finding these ancestors either genealogically or using genetic genealogy is challenging. With the advent of DNA testing, surname and other special interest projects2, tools now exist to facilitate grouping participants in a way that allows one to view populations in historical fashions. This paper references and uses data from several of these public projects, but particularly the Melungeon, Lumbee, Waccamaw, North Carolina Roots and Lost Colony projects3. The Lumbee have long claimed descent from the Lost Colony via their oral history4. The Lumbee DNA Project shows significantly less Native American ancestry than would be expected with 96% European or African Y chromosomal DNA. The Melungeons, long held to be mixed European, African and Native show only one ancestral family with Native DNA5. Clearly more testing would be advantageous in all of these projects. This phenomenon is not limited to these groups, and has been reported by other researchers such as Bolnick (et al, 2006) where she reports finding in 16 Native American populations with northeast or southeast roots that 47% of the families who believe themselves to be full blooded or no less than 75% Native with no paternal European admixture find themselves carrying European or African y-line DNA. -

York River Water Budget

W&M ScholarWorks Reports 1-29-2009 York River Water Budget Carl Hershner Virginia Institute of Marine Science Molly Mitchell Virginia Institute of Marine Science Donna Marie Bilkovic Virginia Institute of Marine Science Julie D. Herman Virginia Institute of Marine Science Center for Coastal Resources Management, Virginia Institute of Marine Science Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/reports Part of the Fresh Water Studies Commons, Hydrology Commons, and the Oceanography Commons Recommended Citation Hershner, C., Mitchell, M., Bilkovic, D. M., Herman, J. D., & Center for Coastal Resources Management, Virginia Institute of Marine Science. (2009) York River Water Budget. Virginia Institute of Marine Science, William & Mary. https://doi.org/10.21220/V56S39 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Reports by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. YORK RIVER WATER BUDGET REPORT By the Center for Coastal Resources Management Virginia Institute of Marine Science January 29, 2009 Authors: Carl Hershner Molly Roggero Donna Bilkovic Julie Herman Table of Contents Introduction............................................................................................................................. 3 Methods of determining instream flow requirement ....................................................................... 4 Hydrological methods.....................................................................................................................