Replacing Cells in Multiple Sclerosis ⁎ Ian D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oligodendrocytes in Development, Myelin Generation and Beyond

cells Review Oligodendrocytes in Development, Myelin Generation and Beyond Sarah Kuhn y, Laura Gritti y, Daniel Crooks and Yvonne Dombrowski * Wellcome-Wolfson Institute for Experimental Medicine, Queen’s University Belfast, Belfast BT9 7BL, UK; [email protected] (S.K.); [email protected] (L.G.); [email protected] (D.C.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +0044-28-9097-6127 These authors contributed equally. y Received: 15 October 2019; Accepted: 7 November 2019; Published: 12 November 2019 Abstract: Oligodendrocytes are the myelinating cells of the central nervous system (CNS) that are generated from oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPC). OPC are distributed throughout the CNS and represent a pool of migratory and proliferative adult progenitor cells that can differentiate into oligodendrocytes. The central function of oligodendrocytes is to generate myelin, which is an extended membrane from the cell that wraps tightly around axons. Due to this energy consuming process and the associated high metabolic turnover oligodendrocytes are vulnerable to cytotoxic and excitotoxic factors. Oligodendrocyte pathology is therefore evident in a range of disorders including multiple sclerosis, schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s disease. Deceased oligodendrocytes can be replenished from the adult OPC pool and lost myelin can be regenerated during remyelination, which can prevent axonal degeneration and can restore function. Cell population studies have recently identified novel immunomodulatory functions of oligodendrocytes, the implications of which, e.g., for diseases with primary oligodendrocyte pathology, are not yet clear. Here, we review the journey of oligodendrocytes from the embryonic stage to their role in homeostasis and their fate in disease. We will also discuss the most common models used to study oligodendrocytes and describe newly discovered functions of oligodendrocytes. -

Myelin Impairs CNS Remyelination by Inhibiting Oligodendrocyte Precursor Cell Differentiation

328 • The Journal of Neuroscience, January 4, 2006 • 26(1):328–332 Brief Communication Myelin Impairs CNS Remyelination by Inhibiting Oligodendrocyte Precursor Cell Differentiation Mark R. Kotter, Wen-Wu Li, Chao Zhao, and Robin J. M. Franklin Cambridge Centre for Brain Repair and Department of Veterinary Medicine, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB3 0ES, United Kingdom Demyelination in the adult CNS can be followed by extensive repair. However, in multiple sclerosis, the differentiation of oligodendrocyte lineage cells present in demyelinated lesions is often inhibited by unknown factors. In this study, we test whether myelin debris, a feature of demyelinated lesions and an in vitro inhibitor of oligodendrocyte precursor differentiation, affects remyelination efficiency. Focal demyelinating lesions were created in the adult rat brainstem, and the naturally generated myelin debris was augmented by the addition of purified myelin. After quantification of myelin basic protein mRNA expression from lesion material obtained by laser capture micro- dissection and supported by histological data, we found a significant impairment of remyelination, attributable to an arrest of the differentiation and not the recruitment of oligodendrocyte precursor cells. These data identify myelin as an inhibitor of remyelination as well as its well documented inhibition of axon regeneration. Key words: regeneration; remyelination; oligodendrocyte precursor cell; myelin; differentiation; macrophage Introduction of myelin debris to efficient remyelination and experimental The adult CNS contains a precursor cell population that responds studies in which delayed phagocytosis of myelin debris is associ- to demyelination by undergoing rapid proliferation, migration, ated with a simultaneous delay of OPC differentiation (Kotter et and differentiation into new oligodendrocytes (Horner et al., al., 2005). -

Myelin Biogenesis Is Associated with Pathological Ultrastructure That Is

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.02.429485; this version posted February 4, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. 1 Myelin biogenesis is associated with pathological ultrastructure that 2 is resolved by microglia during development 3 4 5 Minou Djannatian1,2*, Ulrich Weikert3, Shima Safaiyan1,2, Christoph Wrede4, Cassandra 6 Deichsel1,2, Georg Kislinger1,2, Torben Ruhwedel3, Douglas S. Campbell5, Tjakko van Ham6, 7 Bettina Schmid2, Jan Hegermann4, Wiebke Möbius3, Martina Schifferer2,7, Mikael Simons1,2,7* 8 9 1Institute of Neuronal Cell Biology, Technical University Munich, 80802 Munich, Germany 10 2German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (DZNE), 81377 Munich, Germany 11 3Max-Planck Institute of Experimental Medicine, 37075 Göttingen, Germany 12 4Institute of Functional and Applied Anatomy, Research Core Unit Electron Microscopy, 13 Hannover Medical School, 30625, Hannover, Germany 14 5Department of Neuronal Remodeling, Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Kyoto 15 University, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto 606-8501, Japan. 16 6Department of Clinical Genetics, Erasmus MC, University Medical Center Rotterdam, 3015 CN, 17 the Netherlands 18 7Munich Cluster of Systems Neurology (SyNergy), 81377 Munich, Germany 19 20 *Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected] 21 Keywords 22 Myelination, degeneration, phagocytosis, microglia, oligodendrocytes, phosphatidylserine 23 24 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.02.429485; this version posted February 4, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

The Importance of Myelin

The importance of myelin Nerve cell Nerves carry messages between different parts of the body insulating outer coating of nerves (myelin sheath) Normal nerve Damaged nerve myelin myelin sheath is sheath is intact damaged or destroyed message moves quickly message moves slowly Nerve cells transmit impulses Nerve cells have a long, thin, flexible fibre that transmits impulses. These impulses are electrical signals that travel along the length of the nerve. Nerve fibres are long to enable impulses to travel between distant parts of the body, such as the spinal cord and leg muscles. Myelin speeds up impulses Most nerve fibres are surrounded by an insulating, fatty sheath called myelin, which acts to speed up impulses. The myelin sheath contains periodic breaks called nodes of Ranvier. By jumping from node to node, the impulse can travel much more quickly than if it had to travel along the entire length of the nerve fibre. Myelinated nerves can transmit a signal at speeds as high as 100 metres per second – as fast as a Formula One racing car. normal damaged nerve nerve Loss of myelin leads to a variety of symptoms If the myelin sheath surrounding nerve fibres is damaged or destroyed, transmission of nerve impulses is slowed or blocked. The impulse now has to flow continuously along the whole nerve fibre – a process that is much slower than jumping from node to node. Loss of myelin can also lead to ‘short-circuiting’ of nerve impulses. An area where myelin has been destroyed is called a lesion or plaque. This slowing and ‘short-circuiting’ of nerve impulses by lesions leads to a variety of symptoms related to nervous system activity. -

Regulation of Myelin Structure and Conduction Velocity by Perinodal Astrocytes

Correction NEUROSCIENCE Correction for “Regulation of myelin structure and conduc- tion velocity by perinodal astrocytes,” by Dipankar J. Dutta, Dong Ho Woo, Philip R. Lee, Sinisa Pajevic, Olena Bukalo, William C. Huffman, Hiroaki Wake, Peter J. Basser, Shahriar SheikhBahaei, Vanja Lazarevic, Jeffrey C. Smith, and R. Douglas Fields, which was first published October 29, 2018; 10.1073/ pnas.1811013115 (Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115,11832–11837). The authors note that the following statement should be added to the Acknowledgments: “We acknowledge Dr. Hae Ung Lee for preliminary experiments that informed the ultimate experimental approach.” Published under the PNAS license. Published online June 10, 2019. www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1908361116 12574 | PNAS | June 18, 2019 | vol. 116 | no. 25 www.pnas.org Downloaded by guest on October 2, 2021 Regulation of myelin structure and conduction velocity by perinodal astrocytes Dipankar J. Duttaa,b, Dong Ho Wooa, Philip R. Leea, Sinisa Pajevicc, Olena Bukaloa, William C. Huffmana, Hiroaki Wakea, Peter J. Basserd, Shahriar SheikhBahaeie, Vanja Lazarevicf, Jeffrey C. Smithe, and R. Douglas Fieldsa,1 aSection on Nervous System Development and Plasticity, The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892; bThe Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Inc., Bethesda, MD 20817; cMathematical and Statistical Computing Laboratory, Office of Intramural Research, Center for Information -

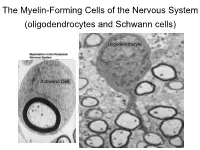

The Myelin-Forming Cells of the Nervous System (Oligodendrocytes and Schwann Cells)

The Myelin-Forming Cells of the Nervous System (oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells) Oligodendrocyte Schwann Cell Oligodendrocyte function Saltatory (jumping) nerve conduction Oligodendroglia PMD PMD Saltatory (jumping) nerve conduction Investigating the Myelinogenic Potential of Individual Oligodendrocytes In Vivo Sparse Labeling of Oligodendrocytes CNPase-GFP Variegated expression under the MBP-enhancer Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Ant Commissure Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Piriform Cortex Corpus Callosum Ant Commissure Characterization of Oligodendrocyte Morphology Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Caudate Putamen Cerebellum Brain Stem Spinal Cord Oligodendrocytes in disease: Cerebral Palsy ! CP major cause of chronic neurological morbidity and mortality in children ! CP incidence now about 3/1000 live births compared to 1/1000 in 1980 when we started intervening for ELBW ! Of all ELBW {gestation 6 mo, Wt. 0.5kg} , 10-15% develop CP ! Prematurely born children prone to white matter injury {WMI}, principle reason for the increase in incidence of CP ! ! 12 Cerebral Palsy Spectrum of white matter injury ! ! Macro Cystic Micro Cystic Gliotic Khwaja and Volpe 2009 13 Rationale for Repair/Remyelination in Multiple Sclerosis Oligodendrocyte specification oligodendrocytes specified from the pMN after MNs - a ventral source of oligodendrocytes -

Extensive Remyelination of the CNS Leads to Functional Recovery

−3 x 10 11 A BC0.35 1 10 0.3 0.9 9 0.25 0.8 0.2 8 0.7 0.15 7 0.6 0.1 0.5 6 Correlation 0.4 0.05 Max. Frequency Max. Power Spectrum 5 0.3 0 4 0.2 −0.05 3 0.1 −0.1 2 0 −0.15 0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1 1.2 1.4 1.6 1.8 2 0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1 1.2 1.4 1.6 1.8 2 0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1 1.2 1.4 1.6 1.8 2 Noise Level Noise Level Noise Level Fig. 5. Stochastic resonance effects. (A) Maximum of the power spectrum peak of the signal given by differences between the level of synchronization between both communities versus the noise level (variance). (B) Maximum in the power spectrum of the signal given by differences between the level of synchronization between both communities versus the noise level. (C) Correlation between the level of synchronization between both communities versus the noise level. Note the stochastic resonance effect that for the same level of fluctuations reveals the optimal emergence of 0.1-Hz global slow oscillations and the emergence of anticorrelated spatiotemporal patterns for both communities. Points (diamonds) correspond to numerical simulations, whereas the line corresponds to a nonlinear least-squared fitting using an ␣-function. www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.0906701106 NEUROSCIENCE GENETICS Correction for ‘‘Extensive remyelination of the CNS leads to Correction for ‘‘Altered tumor formation and evolutionary functional recovery,’’ by I. -

Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein (MOG) Antibody Disease

MOG ANTIBODY DISEASE Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein (MOG) Antibody-Associated Encephalomyelitis WHAT IS MOG ANTIBODY-ASSOCIATED DEMYELINATION? Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) antibody-associated demyelination is an immune-mediated inflammatory process that affects the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord). MOG is a protein that exists on the outer surface of cells that create myelin (an insulating layer around nerve fibers). In a small number of patients, an initial episode of inflammation due to MOG antibodies may be the first manifestation of multiple sclerosis (MS). Most patients may only experience one episode of inflammation, but repeated episodes of central nervous system demyelination can occur in some cases. WHAT ARE THE SYMPTOMS? • Optic neuritis (inflammation of the optic nerve(s)) may be a symptom of MOG antibody- associated demyelination, which may result in painful loss of vision in one or both eyes. • Transverse myelitis (inflammation of the spinal cord) may cause a variety of symptoms that include: o Abnormal sensations. Numbness, tingling, coldness or burning in the arms and/or legs. Some are especially sensitive to the light touch of clothing or to extreme heat or cold. You may feel as if something is tightly wrapping the skin of your chest, abdomen or legs. o Weakness in your arms or legs. Some people notice that they're stumbling or dragging one foot, or heaviness in the legs. Others may develop severe weakness or even total paralysis. o Bladder and bowel problems. This may include needing to urinate more frequently, urinary incontinence, difficulty urinating and constipation. • Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) may cause loss of vision, weakness, numbness, and loss of balance, and altered mental status. -

Lnvited Revie W Growth Factors and Remyelination in The

Histol Histopathol (1997) 12: 459-466 Histology and Histopathology lnvited Revie w Growth factors and remyelination in the CNS R.H. Woodruff and R.J.M. Franklin Departrnent of Clinical Veterinary Medicine and MRC Centre for Brain Repair, University of Carnbridge, Cambridge, UK Summary. It is now well established that there is an multiple sclerosis (MS) (Prineas and Connell, 1979; inherent capacity within the central nervous system Prineas et al., 1989, 1993; Raine and Wu, 1993). (CNS) to remyelinate areas of white matter that have However, remyelination is not universaily consistent or undergone demyelination. However this repair process is sustained, and incomplete remyelination has been not universally consistent or sustained, and persistent reported in gliotoxic lesions of old animals (Gilson and demyelination occurs in a number of situations, most Blakemore, 1993), in certain forms of experimental notably in the chronic multiple sclerosis (MS) plaque. allergic encephalitis (EAE) (Raine et al., 1974), and is a Thus there is a need to investigate ways in which myelin hall-mark feature of the chronic MS plaque. Thus, there deficits within the CNS rnay be restored. One approach is considerable interest in developing ways in which to this problem is to investigate ways in which the persistently demyelinated axons rnay be reinvested with inherent remyelinating capacity of the CNS rnay be myelin sheaths in order to restore secure conduction of stimulated to remyelinate areas of long-term de- impulses. Efforts to address this problem have focussed myelination. The expression of growth factors, which mainly on the use of glial cell transplantation techniques are known to be involved in developmental myelino- to deliver exogenous glial cells into the CNS of hypo- genesis, in areas of demyelination strongly suggests that myelinating myelin mutants (Lachapelle et al., 1984; they are involved in spontaneous remyelination. -

Targeting Myelin Lipid Metabolism As a Potential Therapeutic Strategy in a Model of CMT1A Neuropathy

ARTICLE DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-05420-0 OPEN Targeting myelin lipid metabolism as a potential therapeutic strategy in a model of CMT1A neuropathy R. Fledrich 1,2,3, T. Abdelaal 1,4,5, L. Rasch1,4, V. Bansal6, V. Schütza1,3, B. Brügger7, C. Lüchtenborg7, T. Prukop1,4,8, J. Stenzel1,4, R.U. Rahman6, D. Hermes 1,4, D. Ewers 1,4, W. Möbius 1,9, T. Ruhwedel1, I. Katona 10, J. Weis10, D. Klein11, R. Martini11, W. Brück12, W.C. Müller3, S. Bonn 6,13, I. Bechmann2, K.A. Nave1, R.M. Stassart 1,3,12 & M.W. Sereda1,4 1234567890():,; In patients with Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease 1A (CMT1A), peripheral nerves display aberrant myelination during postnatal development, followed by slowly progressive demye- lination and axonal loss during adult life. Here, we show that myelinating Schwann cells in a rat model of CMT1A exhibit a developmental defect that includes reduced transcription of genes required for myelin lipid biosynthesis. Consequently, lipid incorporation into myelin is reduced, leading to an overall distorted stoichiometry of myelin proteins and lipids with ultrastructural changes of the myelin sheath. Substitution of phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamine in the diet is sufficient to overcome the myelination deficit of affected Schwann cells in vivo. This treatment rescues the number of myelinated axons in the peripheral nerves of the CMT rats and leads to a marked amelioration of neuropathic symptoms. We propose that lipid supplementation is an easily translatable potential therapeutic approach in CMT1A and possibly other dysmyelinating neuropathies. 1 Department of Neurogenetics, Max-Planck-Institute of Experimental Medicine, Göttingen 37075, Germany. -

The Effects of Normal Aging on Myelin and Nerve Fibers: a Review∗

Journal of Neurocytology 31, 581–593 (2002) The effects of normal aging on myelin and nerve fibers: A review∗ ALAN PETERS Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology, Boston University School of Medicine, 715, Albany Street, Boston, MA 02118, USA [email protected] Received 7 January 2003; revised 4 March 2003; accepted 5 March 2003 Abstract It was believed that the cause of the cognitive decline exhibited by human and non-human primates during normal aging was a loss of cortical neurons. It is now known that significant numbers of cortical neurons are not lost and other bases for the cognitive decline have been sought. One contributing factor may be changes in nerve fibers. With age some myelin sheaths exhibit degenerative changes, such as the formation of splits containing electron dense cytoplasm, and the formation on myelin balloons. It is suggested that such degenerative changes lead to cognitive decline because they cause changes in conduction velocity, resulting in a disruption of the normal timing in neuronal circuits. Yet as degeneration occurs, other changes, such as the formation of redundant myelin and increasing thickness suggest of sheaths, suggest some myelin formation is continuing during aging. Another indication of this is that oligodendrocytes increase in number with age. In addition to the myelin changes, stereological studies have shown a loss of nerve fibers from the white matter of the cerebral hemispheres of humans, while other studies have shown a loss of nerve fibers from the optic nerves and anterior commissure in monkeys. It is likely that such nerve fiber loss also contributes to cognitive decline, because of the consequent decrease in connections between neurons. -

Schwann Cells, but Not Oligodendrocytes, Depend Strictly

RESEARCH ARTICLE Schwann cells, but not Oligodendrocytes, Depend Strictly on Dynamin 2 Function Daniel Gerber1†, Monica Ghidinelli1†, Elisa Tinelli1, Christian Somandin1, Joanne Gerber1, Jorge A Pereira1, Andrea Ommer1, Gianluca Figlia1, Michaela Miehe1, Lukas G Na¨ geli1, Vanessa Suter1, Valentina Tadini1, Pa´ ris NM Sidiropoulos1, Carsten Wessig2, Klaus V Toyka2, Ueli Suter1* 1Department of Biology, Institute of Molecular Health Sciences, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, ETH Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland; 2Department of Neurology, University Hospital of Wu¨ rzburg, University of Wu¨ rzburg, Wu¨ rzburg, Germany Abstract Myelination requires extensive plasma membrane rearrangements, implying that molecules controlling membrane dynamics play prominent roles. The large GTPase dynamin 2 (DNM2) is a well-known regulator of membrane remodeling, membrane fission, and vesicular trafficking. Here, we genetically ablated Dnm2 in Schwann cells (SCs) and in oligodendrocytes of mice. Dnm2 deletion in developing SCs resulted in severely impaired axonal sorting and myelination onset. Induced Dnm2 deletion in adult SCs caused a rapidly-developing peripheral neuropathy with abundant demyelination. In both experimental settings, mutant SCs underwent prominent cell death, at least partially due to cytokinesis failure. Strikingly, when Dnm2 was deleted in adult SCs, non-recombined SCs still expressing DNM2 were able to remyelinate fast and efficiently, accompanied by neuropathy remission. These findings reveal a remarkable self-healing capability of peripheral nerves that are affected by SC loss. In the central nervous system, however, *For correspondence: we found no major defects upon Dnm2 deletion in oligodendrocytes. [email protected] DOI: https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.42404.001 †These authors contributed equally to this work Competing interests: The Introduction authors declare that no Motor, sensory, and cognitive functions of the nervous system require rapid and refined impulse competing interests exist.