Targeting Myelin Lipid Metabolism As a Potential Therapeutic Strategy in a Model of CMT1A Neuropathy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise and Fall of the Bovine Corpus Luteum

University of Nebraska Medical Center DigitalCommons@UNMC Theses & Dissertations Graduate Studies Spring 5-6-2017 The Rise and Fall of the Bovine Corpus Luteum Heather Talbott University of Nebraska Medical Center Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unmc.edu/etd Part of the Biochemistry Commons, Molecular Biology Commons, and the Obstetrics and Gynecology Commons Recommended Citation Talbott, Heather, "The Rise and Fall of the Bovine Corpus Luteum" (2017). Theses & Dissertations. 207. https://digitalcommons.unmc.edu/etd/207 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@UNMC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNMC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE RISE AND FALL OF THE BOVINE CORPUS LUTEUM by Heather Talbott A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of the University of Nebraska Graduate College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Graduate Program Under the Supervision of Professor John S. Davis University of Nebraska Medical Center Omaha, Nebraska May, 2017 Supervisory Committee: Carol A. Casey, Ph.D. Andrea S. Cupp, Ph.D. Parmender P. Mehta, Ph.D. Justin L. Mott, Ph.D. i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation was supported by the Agriculture and Food Research Initiative from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) Pre-doctoral award; University of Nebraska Medical Center Graduate Student Assistantship; University of Nebraska Medical Center Exceptional Incoming Graduate Student Award; the VA Nebraska-Western Iowa Health Care System Department of Veterans Affairs; and The Olson Center for Women’s Health, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Nebraska Medical Center. -

The Role of Phospholipases A2 in Schizophrenia

Molecular Psychiatry (2006) 11, 547–556 & 2006 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 1359-4184/06 $30.00 www.nature.com/mp FEATURE REVIEW The role of phospholipases A2 in schizophrenia MH Law1, RGH Cotton1 and GE Berger1,2 1Genomic Disorders Research Centre, Melbourne, VI, Australia and 2ORYGEN Research Centre, Melbourne, VI, Australia A range of neurotransmitter systems have been implicated in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia based on the antidopaminergic activities of antipsychotic medications, and chemicals that can induce psychotic-like symptoms, such as ketamine or PCP. Such neurotransmitter systems often mediate their cellular response via G-protein-coupled release of arachidonic acid (AA) via the activation of phospholipases A2 (PLA2s). The interaction of three PLA2s are important for the regulation of the release of AA – phospholipase A2 Group 2 A, phospholipase A2 Group 4A and phospholipase A2 Group 6A. Gene variations of these three key enzymes have been associated with schizophrenia with conflicting results. Preclinical data suggest that the activity of these three enzymes are associated with monoaminergic neurotransmission, and may contribute to the differential efficacy of antipsychotic medications, as well as other biological changes thought to underlie schizophrenia, such as altered neurodevelopment and synaptic remodelling. We review the evidence and discuss the potential roles of these three key enzymes for schizophrenia with particular emphasis on published association studies. Molecular Psychiatry (2006) 11, 547–556. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4001819; published online 4 April 2006 Keywords: review; schizophrenia/genetics; PLA2/genetics; arachidonic acid; common diseases; PLA2/schizophrenia Introduction (PLA2GVIA, PLA2G6A), dopamine, serotonin, G- protein-coupled receptor, eicosanoids and phospho- Neurotransmitters, such as dopamine, serotonin and lipids. -

![Biopan: a Web-Based Tool to Explore Mammalian Lipidome Metabolic Pathways on LIPID MAPS[Version 1; Peer Review: 2 Approved]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2812/biopan-a-web-based-tool-to-explore-mammalian-lipidome-metabolic-pathways-on-lipid-maps-version-1-peer-review-2-approved-752812.webp)

Biopan: a Web-Based Tool to Explore Mammalian Lipidome Metabolic Pathways on LIPID MAPS[Version 1; Peer Review: 2 Approved]

F1000Research 2021, 10:4 Last updated: 29 JAN 2021 SOFTWARE TOOL ARTICLE BioPAN: a web-based tool to explore mammalian lipidome metabolic pathways on LIPID MAPS [version 1; peer review: 2 approved] Caroline Gaud 1, Bebiana C. Sousa 2, An Nguyen1, Maria Fedorova3, Zhixu Ni 3, Valerie B. O’Donnell4, Michael J.O. Wakelam2+, Simon Andrews1, Andrea F. Lopez-Clavijo 2 1Bioinformatics Group, Babraham Institute, Babraham Research Campus, Cambridge, CB22 3AT, UK 2Lipidomics facility, Babraham Institute, Babraham Research Campus, Cambridge, CB22 3AT, UK 3Institute of Bioanalytical Chemistry, Faculty of Chemistry and Mineralogy, Center for Biotechnology and Biomedicine, Universität Leipzig, Leipzig, 04109, Germany 4Systems Immunity Research Institute, School of Medicine, Cardiff University, Cardiff, CF14 4XN, UK + Deceased author v1 First published: 06 Jan 2021, 10:4 Open Peer Review https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.28022.1 Latest published: 06 Jan 2021, 10:4 https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.28022.1 Reviewer Status Invited Reviewers Abstract Lipidomics increasingly describes the quantitation using mass 1 2 spectrometry of all lipids present in a biological sample. As the power of lipidomics protocols increase, thousands of lipid molecular species version 1 from multiple categories can now be profiled in a single experiment. 06 Jan 2021 report report Observed changes due to biological differences often encompass large numbers of structurally-related lipids, with these being 1. Amaury Cazenave Gassiot , Yong Loo Lin regulated by enzymes from well-known metabolic pathways. As lipidomics datasets increase in complexity, the interpretation of their School of Medicine, Singapore, Singapore results becomes more challenging. BioPAN addresses this by 2. -

Myelin Biogenesis Is Associated with Pathological Ultrastructure That Is

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.02.429485; this version posted February 4, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. 1 Myelin biogenesis is associated with pathological ultrastructure that 2 is resolved by microglia during development 3 4 5 Minou Djannatian1,2*, Ulrich Weikert3, Shima Safaiyan1,2, Christoph Wrede4, Cassandra 6 Deichsel1,2, Georg Kislinger1,2, Torben Ruhwedel3, Douglas S. Campbell5, Tjakko van Ham6, 7 Bettina Schmid2, Jan Hegermann4, Wiebke Möbius3, Martina Schifferer2,7, Mikael Simons1,2,7* 8 9 1Institute of Neuronal Cell Biology, Technical University Munich, 80802 Munich, Germany 10 2German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (DZNE), 81377 Munich, Germany 11 3Max-Planck Institute of Experimental Medicine, 37075 Göttingen, Germany 12 4Institute of Functional and Applied Anatomy, Research Core Unit Electron Microscopy, 13 Hannover Medical School, 30625, Hannover, Germany 14 5Department of Neuronal Remodeling, Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Kyoto 15 University, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto 606-8501, Japan. 16 6Department of Clinical Genetics, Erasmus MC, University Medical Center Rotterdam, 3015 CN, 17 the Netherlands 18 7Munich Cluster of Systems Neurology (SyNergy), 81377 Munich, Germany 19 20 *Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected] 21 Keywords 22 Myelination, degeneration, phagocytosis, microglia, oligodendrocytes, phosphatidylserine 23 24 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.02.429485; this version posted February 4, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

The Importance of Myelin

The importance of myelin Nerve cell Nerves carry messages between different parts of the body insulating outer coating of nerves (myelin sheath) Normal nerve Damaged nerve myelin myelin sheath is sheath is intact damaged or destroyed message moves quickly message moves slowly Nerve cells transmit impulses Nerve cells have a long, thin, flexible fibre that transmits impulses. These impulses are electrical signals that travel along the length of the nerve. Nerve fibres are long to enable impulses to travel between distant parts of the body, such as the spinal cord and leg muscles. Myelin speeds up impulses Most nerve fibres are surrounded by an insulating, fatty sheath called myelin, which acts to speed up impulses. The myelin sheath contains periodic breaks called nodes of Ranvier. By jumping from node to node, the impulse can travel much more quickly than if it had to travel along the entire length of the nerve fibre. Myelinated nerves can transmit a signal at speeds as high as 100 metres per second – as fast as a Formula One racing car. normal damaged nerve nerve Loss of myelin leads to a variety of symptoms If the myelin sheath surrounding nerve fibres is damaged or destroyed, transmission of nerve impulses is slowed or blocked. The impulse now has to flow continuously along the whole nerve fibre – a process that is much slower than jumping from node to node. Loss of myelin can also lead to ‘short-circuiting’ of nerve impulses. An area where myelin has been destroyed is called a lesion or plaque. This slowing and ‘short-circuiting’ of nerve impulses by lesions leads to a variety of symptoms related to nervous system activity. -

The Metabolic Serine Hydrolases and Their Functions in Mammalian Physiology and Disease Jonathan Z

REVIEW pubs.acs.org/CR The Metabolic Serine Hydrolases and Their Functions in Mammalian Physiology and Disease Jonathan Z. Long* and Benjamin F. Cravatt* The Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology and Department of Chemical Physiology, The Scripps Research Institute, 10550 North Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, California 92037, United States CONTENTS 2.4. Other Phospholipases 6034 1. Introduction 6023 2.4.1. LIPG (Endothelial Lipase) 6034 2. Small-Molecule Hydrolases 6023 2.4.2. PLA1A (Phosphatidylserine-Specific 2.1. Intracellular Neutral Lipases 6023 PLA1) 6035 2.1.1. LIPE (Hormone-Sensitive Lipase) 6024 2.4.3. LIPH and LIPI (Phosphatidic Acid-Specific 2.1.2. PNPLA2 (Adipose Triglyceride Lipase) 6024 PLA1R and β) 6035 2.1.3. MGLL (Monoacylglycerol Lipase) 6025 2.4.4. PLB1 (Phospholipase B) 6035 2.1.4. DAGLA and DAGLB (Diacylglycerol Lipase 2.4.5. DDHD1 and DDHD2 (DDHD Domain R and β) 6026 Containing 1 and 2) 6035 2.1.5. CES3 (Carboxylesterase 3) 6026 2.4.6. ABHD4 (Alpha/Beta Hydrolase Domain 2.1.6. AADACL1 (Arylacetamide Deacetylase-like 1) 6026 Containing 4) 6036 2.1.7. ABHD6 (Alpha/Beta Hydrolase Domain 2.5. Small-Molecule Amidases 6036 Containing 6) 6027 2.5.1. FAAH and FAAH2 (Fatty Acid Amide 2.1.8. ABHD12 (Alpha/Beta Hydrolase Domain Hydrolase and FAAH2) 6036 Containing 12) 6027 2.5.2. AFMID (Arylformamidase) 6037 2.2. Extracellular Neutral Lipases 6027 2.6. Acyl-CoA Hydrolases 6037 2.2.1. PNLIP (Pancreatic Lipase) 6028 2.6.1. FASN (Fatty Acid Synthase) 6037 2.2.2. PNLIPRP1 and PNLIPR2 (Pancreatic 2.6.2. -

Regulation of Myelin Structure and Conduction Velocity by Perinodal Astrocytes

Correction NEUROSCIENCE Correction for “Regulation of myelin structure and conduc- tion velocity by perinodal astrocytes,” by Dipankar J. Dutta, Dong Ho Woo, Philip R. Lee, Sinisa Pajevic, Olena Bukalo, William C. Huffman, Hiroaki Wake, Peter J. Basser, Shahriar SheikhBahaei, Vanja Lazarevic, Jeffrey C. Smith, and R. Douglas Fields, which was first published October 29, 2018; 10.1073/ pnas.1811013115 (Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115,11832–11837). The authors note that the following statement should be added to the Acknowledgments: “We acknowledge Dr. Hae Ung Lee for preliminary experiments that informed the ultimate experimental approach.” Published under the PNAS license. Published online June 10, 2019. www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1908361116 12574 | PNAS | June 18, 2019 | vol. 116 | no. 25 www.pnas.org Downloaded by guest on October 2, 2021 Regulation of myelin structure and conduction velocity by perinodal astrocytes Dipankar J. Duttaa,b, Dong Ho Wooa, Philip R. Leea, Sinisa Pajevicc, Olena Bukaloa, William C. Huffmana, Hiroaki Wakea, Peter J. Basserd, Shahriar SheikhBahaeie, Vanja Lazarevicf, Jeffrey C. Smithe, and R. Douglas Fieldsa,1 aSection on Nervous System Development and Plasticity, The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892; bThe Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Inc., Bethesda, MD 20817; cMathematical and Statistical Computing Laboratory, Office of Intramural Research, Center for Information -

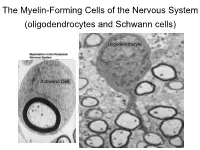

The Myelin-Forming Cells of the Nervous System (Oligodendrocytes and Schwann Cells)

The Myelin-Forming Cells of the Nervous System (oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells) Oligodendrocyte Schwann Cell Oligodendrocyte function Saltatory (jumping) nerve conduction Oligodendroglia PMD PMD Saltatory (jumping) nerve conduction Investigating the Myelinogenic Potential of Individual Oligodendrocytes In Vivo Sparse Labeling of Oligodendrocytes CNPase-GFP Variegated expression under the MBP-enhancer Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Ant Commissure Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Piriform Cortex Corpus Callosum Ant Commissure Characterization of Oligodendrocyte Morphology Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Caudate Putamen Cerebellum Brain Stem Spinal Cord Oligodendrocytes in disease: Cerebral Palsy ! CP major cause of chronic neurological morbidity and mortality in children ! CP incidence now about 3/1000 live births compared to 1/1000 in 1980 when we started intervening for ELBW ! Of all ELBW {gestation 6 mo, Wt. 0.5kg} , 10-15% develop CP ! Prematurely born children prone to white matter injury {WMI}, principle reason for the increase in incidence of CP ! ! 12 Cerebral Palsy Spectrum of white matter injury ! ! Macro Cystic Micro Cystic Gliotic Khwaja and Volpe 2009 13 Rationale for Repair/Remyelination in Multiple Sclerosis Oligodendrocyte specification oligodendrocytes specified from the pMN after MNs - a ventral source of oligodendrocytes -

DNA–Protein Interactions DNA–Protein Interactions

MethodsMethods inin MolecularMolecular BiologyBiologyTM VOLUME 148 DNA–ProteinDNA–Protein InteractionsInteractions PrinciplesPrinciples andand ProtocolsProtocols SECOND EDITION EditedEdited byby TTomom MossMoss POLII TFIIH HUMANA PRESS M e t h o d s i n M o l e c u l a r B I O L O G Y TM John M. Walker, Series Editor 178.`Antibody Phage Display: Methods and Protocols, edited by 147. Affinity Chromatography: Methods and Protocols, edited by Philippa M. O’Brien and Robert Aitken, 2001 Pascal Bailon, George K. Ehrlich, Wen-Jian Fung, and 177. Two-Hybrid Systems: Methods and Protocols, edited by Paul Wolfgang Berthold, 2000 N. MacDonald, 2001 146. Mass Spectrometry of Proteins and Peptides, edited by John 176. Steroid Receptor Methods: Protocols and Assays, edited by R. Chapman, 2000 Benjamin A. Lieberman, 2001 145. Bacterial Toxins: Methods and Protocols, edited by Otto Holst, 175. Genomics Protocols, edited by Michael P. Starkey and 2000 Ramnath Elaswarapu, 2001 144. Calpain Methods and Protocols, edited by John S. Elce, 2000 174. Epstein-Barr Virus Protocols, edited by Joanna B. Wilson 143. Protein Structure Prediction: Methods and Protocols, and Gerhard H. W. May, 2001 edited by David Webster, 2000 173. Calcium-Binding Protein Protocols, Volume 2: Methods and 142. Transforming Growth Factor-Beta Protocols, edited by Philip Techniques, edited by Hans J. Vogel, 2001 H. Howe, 2000 172. Calcium-Binding Protein Protocols, Volume 1: Reviews and 141. Plant Hormone Protocols, edited by Gregory A. Tucker and Case Histories, edited by Hans J. Vogel, 2001 Jeremy A. Roberts, 2000 171. Proteoglycan Protocols, edited by Renato V. Iozzo, 2001 140. -

Phosphoproteomics Identify Arachidonic-Acid-Regulated Signal Transduction Pathways Modulating Macrophage Functions with Implications for Ovarian Cancer

Phosphoproteomics identify arachidonic-acid-regulated signal transduction pathways modulating macrophage functions with implications for ovarian cancer Raimund Dietze1¶, Mohamad K. Hammoud1¶, María Gómez-Serrano1, Annika Unger1, Tim Bieringer1§, Florian Finkernagel1, Anna M. Sokol2,3, Andrea Nist4, Thorsten Stiewe4, Silke Reinartz1, Viviane Ponath5, Christian Preußer5, Elke Pogge von Strandmann5, Sabine Müller- Brüsselbach1, Johannes Graumann2,3 and Rolf Müller1* 1Tranlational OncologY Group, Center for Tumor BiologY and Immunology, Philipps University, Marburg, GermanY 2Biomolecular Mass Spectrometry, Max-Planck-Institute for Heart and Lung Research, Bad Nauheim, GermanY 3The German Centre for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK), Partner Site Rhine-Main, Max Planck Institute for Heart and Lung Research, Bad Nauheim, GermanY 4Genomics Core Facility, Philipps UniversitY, Marburg, GermanY 5Institute for Tumor Immunology, Philipps University, Marburg, GermanY §Present address: Hochschule Landshut, 84036 Landshut, GermanY ¶Equal contribution *Corresponding author: Rolf Müller, Center for Tumor Biology and Immunology (ZTI), Philipps University, Hans-Meerwein-Strasse 3, 35043 Marburg, GermanY. Email: [email protected]. Phone: +49 6421 2866236. Running title: Signaling pathways of arachidonic acid in macrophages 1 Abstract Arachidonic acid (AA) is a polYunsaturated fatty acid present at high concentrations in the ovarian cancer (OC) microenvironment and associated with a poor clinical outcome. In the present studY, we have unraveled a potential link between AA and macrophage functions. Methods: AA-triggered signal transduction was studied in primary monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs) by phosphoproteomics, transcriptional profiling, measurement of intracellular Ca2+ accumulation and reactive oxygen species production in conjunction with bioinformatic analyses. Functional effects were investigated by actin filament staining, quantification of macropinocytosis and analysis of extracellular vesicle release. -

Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein (MOG) Antibody Disease

MOG ANTIBODY DISEASE Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein (MOG) Antibody-Associated Encephalomyelitis WHAT IS MOG ANTIBODY-ASSOCIATED DEMYELINATION? Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) antibody-associated demyelination is an immune-mediated inflammatory process that affects the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord). MOG is a protein that exists on the outer surface of cells that create myelin (an insulating layer around nerve fibers). In a small number of patients, an initial episode of inflammation due to MOG antibodies may be the first manifestation of multiple sclerosis (MS). Most patients may only experience one episode of inflammation, but repeated episodes of central nervous system demyelination can occur in some cases. WHAT ARE THE SYMPTOMS? • Optic neuritis (inflammation of the optic nerve(s)) may be a symptom of MOG antibody- associated demyelination, which may result in painful loss of vision in one or both eyes. • Transverse myelitis (inflammation of the spinal cord) may cause a variety of symptoms that include: o Abnormal sensations. Numbness, tingling, coldness or burning in the arms and/or legs. Some are especially sensitive to the light touch of clothing or to extreme heat or cold. You may feel as if something is tightly wrapping the skin of your chest, abdomen or legs. o Weakness in your arms or legs. Some people notice that they're stumbling or dragging one foot, or heaviness in the legs. Others may develop severe weakness or even total paralysis. o Bladder and bowel problems. This may include needing to urinate more frequently, urinary incontinence, difficulty urinating and constipation. • Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) may cause loss of vision, weakness, numbness, and loss of balance, and altered mental status. -

Monoacylglycerol Lipase Inhibition in Human and Rodent Systems Supports Clinical Evaluation of Endocannabinoid Modulators S

Supplemental material to this article can be found at: http://jpet.aspetjournals.org/content/suppl/2018/10/10/jpet.118.252296.DC1 1521-0103/367/3/494–508$35.00 https://doi.org/10.1124/jpet.118.252296 THE JOURNAL OF PHARMACOLOGY AND EXPERIMENTAL THERAPEUTICS J Pharmacol Exp Ther 367:494–508, December 2018 Copyright ª 2018 The Author(s). This is an open access article distributed under the CC BY Attribution 4.0 International license. Monoacylglycerol Lipase Inhibition in Human and Rodent Systems Supports Clinical Evaluation of Endocannabinoid Modulators s Jason R. Clapper, Cassandra L. Henry, Micah J. Niphakis, Anna M. Knize, Aundrea R. Coppola, Gabriel M. Simon, Nhi Ngo, Rachel A. Herbst, Dylan M. Herbst, Alex W. Reed, Justin S. Cisar, Olivia D. Weber, Andreu Viader, Jessica P. Alexander, Mark L. Cunningham, Todd K. Jones, Iain P. Fraser, Cheryl A. Grice, R. Alan B. Ezekowitz, ’ Gary P. O Neill, and Jacqueline L. Blankman Downloaded from Abide Therapeutics, San Diego, California Received July 26, 2018; accepted October 5, 2018 ABSTRACT Monoacylglycerol lipase (MGLL) is the primary degradative whether selective MGLL inhibition would affect prostanoid pro- jpet.aspetjournals.org enzyme for the endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2- duction in several human assays known to be sensitive AG). The first MGLL inhibitors have recently entered clinical to cyclooxygenase inhibitors. ABD-1970 robustly elevated brain development for the treatment of neurologic disorders. To 2-AG content and displayed antinociceptive and antipru- support this clinical path, we report the pharmacological ritic activity in a battery of rodent models (ED50 values of characterization of the highly potent and selective MGLL inhibitor 1–2 mg/kg).