Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

B.Sc. II YEAR CHORDATA

B.Sc. II YEAR CHORDATA CHORDATA 16SCCZO3 Dr. R. JENNI & Dr. R. DHANAPAL DEPARTMENT OF ZOOLOGY M. R. GOVT. ARTS COLLEGE MANNARGUDI CONTENTS CHORDATA COURSE CODE: 16SCCZO3 Block and Unit title Block I (Primitive chordates) 1 Origin of chordates: Introduction and charterers of chordates. Classification of chordates up to order level. 2 Hemichordates: General characters and classification up to order level. Study of Balanoglossus and its affinities. 3 Urochordata: General characters and classification up to order level. Study of Herdmania and its affinities. 4 Cephalochordates: General characters and classification up to order level. Study of Branchiostoma (Amphioxus) and its affinities. 5 Cyclostomata (Agnatha) General characters and classification up to order level. Study of Petromyzon and its affinities. Block II (Lower chordates) 6 Fishes: General characters and classification up to order level. Types of scales and fins of fishes, Scoliodon as type study, migration and parental care in fishes. 7 Amphibians: General characters and classification up to order level, Rana tigrina as type study, parental care, neoteny and paedogenesis. 8 Reptilia: General characters and classification up to order level, extinct reptiles. Uromastix as type study. Identification of poisonous and non-poisonous snakes and biting mechanism of snakes. 9 Aves: General characters and classification up to order level. Study of Columba (Pigeon) and Characters of Archaeopteryx. Flight adaptations & bird migration. 10 Mammalia: General characters and classification up -

Hyaenodontidae (Creodonta, Mammalia) and the Position of Systematics in Evolutionary Biology

Hyaenodontidae (Creodonta, Mammalia) and the Position of Systematics in Evolutionary Biology by Paul David Polly B.A. (University of Texas at Austin) 1987 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Paleontology in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA at BERKELEY Committee in charge: Professor William A. Clemens, Chair Professor Kevin Padian Professor James L. Patton Professor F. Clark Howell 1993 Hyaenodontidae (Creodonta, Mammalia) and the Position of Systematics in Evolutionary Biology © 1993 by Paul David Polly To P. Reid Hamilton, in memory. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ix Acknowledgments xi Chapter One--Revolution and Evolution in Taxonomy: Mammalian Classification Before and After Darwin 1 Introduction 2 The Beginning of Modern Taxonomy: Linnaeus and his Predecessors 5 Cuvier's Classification 10 Owen's Classification 18 Post-Darwinian Taxonomy: Revolution and Evolution in Classification 24 Kovalevskii's Classification 25 Huxley's Classification 28 Cope's Classification 33 Early 20th Century Taxonomy 42 Simpson and the Evolutionary Synthesis 46 A Box Model of Classification 48 The Content of Simpson's 1945 Classification 50 Conclusion 52 Acknowledgments 56 Bibliography 56 Figures 69 Chapter Two: Hyaenodontidae (Creodonta, Mammalia) from the Early Eocene Four Mile Fauna and Their Biostratigraphic Implications 78 Abstract 79 Introduction 79 Materials and Methods 80 iv Systematic Paleontology 80 The Four Mile Fauna and Wasatchian Biostratigraphic Zonation 84 Conclusion 86 Acknowledgments 86 Bibliography 86 Figures 87 Chapter Three: A New Genus Eurotherium (Creodonta, Mammalia) in Reference to Taxonomic Problems with Some Eocene Hyaenodontids from Eurasia (With B. Lange-Badré) 89 Résumé 90 Abstract 90 Version française abrégéé 90 Introduction 93 Acknowledgments 96 Bibliography 96 Table 3.1: Original and Current Usages of Genera and Species 99 Table 3.2: Species Currently Included in Genera Discussed in Text 101 Chapter Four: The skeleton of Gazinocyon vulpeculus n. -

Chapter 32: Mammals Research

Chapter 32 Organizer Mammals Refer to pages 4T-5T of the Teacher Guide for an explanation of the National Science Education Standards correlations. Teacher Classroom Resources Activities/FeaturesObjectivesSection MastersSection TransparenciesReproducible Reinforcement and Study Guide, pp. 141-142 L2 Section Focus Transparency 77 L1 ELL Section 32.1 1. Distinguish mammalian characteristics. MiniLab 32-1: Anatomy of a Tooth, p. 869 Section 32.1 2. Explain how the characteristics of mam- Problem-Solving Lab 32-1, p. 870 Concept Mapping, p. 32 L3 ELL Basic Concepts Transparency 58 L2 ELL Mammal mals enable them to adapt to most habi- MiniLab 32-2: Mammal Skeletons, p. 871 Mammal Critical Thinking/Problem Solving, p. 32 L3 Basic Concepts Transparency 59 L2 ELL Characteristics tats on Earth. Inside Story: A Mammal, p. 872 Characteristics BioLab and MiniLab Worksheets, pp. 143-144 L2 Reteaching Skills Transparency 47 L1P ELL National Science Education Careers in Biology: Animal Trainer, p. 873 Laboratory Manual, pp. 229-238P L2 P Standards UCP.1-5; A.1, A.2; Internet BioLab: Domestic Dogs Wanted, Content Mastery, pp. 157-158, 160 L1 P B.2; C.3, C.5, C.6 (1 session, p. 882 P Tech Prep Applications, pp. 41-42 L2 P P 1 block) Biology & Society: Do we need zoos? p. 884 P LS P LS P LS Reinforcement and Study Guide, pp. 143-144 L2 Section Focus Transparency 78 L1P ELL Section 32.2 LS Section 32.2 3. Distinguish among the three groups of Focus On Placental Mammals, p. 876 BioLab and MiniLab Worksheets,LS pp. -

General Biology Classification: Mammals

High School Science Virtual Learning General Biology Classification: Mammals May 15, 2020 High School Biology Lesson: May 15, 2020 Objective/Learning Target: Students will be able to learn about and explain the classification (binomial nomenclature) of Mammals. Let’s Get Started: Let’s get started: 1. What is one main difference between amphibians and reptiles? 2. What is the phylum (classification) name given to both amphibians and reptiles? Let’s Get Started: Let’s get started: Answer Key 1. Amphibians use both lungs and gills, use toxic skin secretions and bit for defense, have webbed five digit limbs, skin texture is smooth and moist, external fertilization, etc. Reptiles have lungs, use nails and teeth, have four limbs (except snakes), dry and scaly skin, internal fertilization, amniotic eggs, etc. 2. Chordata Let’s Get Started: Key Information Some key information before we dive much further will be necessary for you to understand. Mammals fall under the Animalia Kingdom and the Phylum known as Chordata. Their subphylum is Vertebrata because they have a backbone that is segmented. Further, mammals fall into the class of Mammalia in which there are three subclasses and 19 orders. There are three physical characteristics that are distinct from other animals for mammals. These include: 1. Hair 2. Production of Milk 3. Many aspects of the Skeleton, especially the Skull Let’s Get Started: Lesson Activity: 1. Watch this video. While you are doing so, take careful notes about the different subclasses of mammals. Organize your notes into a chart that resembles something like this. If there is a style of chart that you would prefer, use that. -

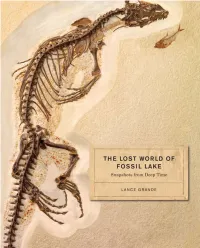

The Lost World of Fossil Lake

Snapshots from Deep Time THE LOST WORLD of FOSSIL LAKE lance grande With photography by Lance Grande and John Weinstein The University of Chicago Press | Chicago and London Ray-Finned Fishes ( Superclass Actinopterygii) The vast majority of fossils that have been mined from the FBM over the last century and a half have been fossil ray-finned fishes, or actinopterygians. Literally millions of complete fossil ray-finned fish skeletons have been excavated from the FBM, the majority of which have been recovered in the last 30 years because of a post- 1970s boom in the number of commercial fossil operations. Almost all vertebrate fossils in the FBM are actinopterygian fishes, with perhaps 1 out of 2,500 being a stingray and 1 out of every 5,000 to 10,000 being a tetrapod. Some actinopterygian groups are still poorly understood be- cause of their great diversity. One such group is the spiny-rayed suborder Percoidei with over 3,200 living species (including perch, bass, sunfishes, and thousands of other species with pointed spines in their fins). Until the living percoid species are better known, ac- curate classification of the FBM percoids (†Mioplosus, †Priscacara, †Hypsiprisca, and undescribed percoid genera) will be unsatisfac- tory. 107 Length measurements given here for actinopterygians were made from the tip of the snout to the very end of the tail fin (= total length). The FBM actinop- terygian fishes presented below are as follows: Paddlefishes (Order Acipenseriformes, Family Polyodontidae) Paddlefishes are relatively rare in the FBM, represented by the species †Cros- sopholis magnicaudatus (fig. 48). †Crossopholis has a very long snout region, or “paddle.” Living paddlefishes are sometimes called “spoonbills,” “spoonies,” or even “spoonbill catfish.” The last of those common names is misleading because paddlefishes are not closely related to catfishes and are instead close relatives of sturgeons. -

The Biology of Marine Mammals

Romero, A. 2009. The Biology of Marine Mammals. The Biology of Marine Mammals Aldemaro Romero, Ph.D. Arkansas State University Jonesboro, AR 2009 2 INTRODUCTION Dear students, 3 Chapter 1 Introduction to Marine Mammals 1.1. Overture Humans have always been fascinated with marine mammals. These creatures have been the basis of mythical tales since Antiquity. For centuries naturalists classified them as fish. Today they are symbols of the environmental movement as well as the source of heated controversies: whether we are dealing with the clubbing pub seals in the Arctic or whaling by industrialized nations, marine mammals continue to be a hot issue in science, politics, economics, and ethics. But if we want to better understand these issues, we need to learn more about marine mammal biology. The problem is that, despite increased research efforts, only in the last two decades we have made significant progress in learning about these creatures. And yet, that knowledge is largely limited to a handful of species because they are either relatively easy to observe in nature or because they can be studied in captivity. Still, because of television documentaries, ‘coffee-table’ books, displays in many aquaria around the world, and a growing whale and dolphin watching industry, people believe that they have a certain familiarity with many species of marine mammals (for more on the relationship between humans and marine mammals such as whales, see Ellis 1991, Forestell 2002). As late as 2002, a new species of beaked whale was being reported (Delbout et al. 2002), in 2003 a new species of baleen whale was described (Wada et al. -

Chapter 32: Mammals

0840-0840 C32CO BDOL-829900 8/4/04 11:01 PM Page 840 Mammals What You’ll Learn ■ You will identify the charac- teristics of mammals. ■ You will compare and contrast three groups of living mam- mals and examine their rela- tionships to their ancient ancestors. Why It’s Important Mammals play a major role in most ecosystems on Earth because they are one of the most successful groups of ani- mals. Humans are mammals, so studying mammal characteristics provides information about humans as well. Understanding the Photo Giraffes are the tallest mam- mals. Newborn giraffes average 1.8 meters and can grow to be about 5.5 meters as adults. They have long legs and can run quickly—about 60 km/h. Their long legs, as well as their long necks, help them reach leaves in tall acacia trees. Visit ca.bdol.glencoe.com to • study the entire chapter online • access Web Links for more information and activities on mammals • review content with the Interactive Tutor and self- check quizzes 840 Shin Yoshino/Minden Pictures 0841-0847 C32S1 BDOL-829900 8/4/04 10:39 PM Page 841 Mammal Characteristics 32.1 SECTION PREVIEW Objectives Mammals Make the following Foldable to help you identify Distinguish mammalian main characteristics of mammals. characteristics. Explain how the charac- STEP 1 STEP 2 teristics of mammals Fold a vertical Cut along every enable them to adapt to sheet of notebook paper fourth line of only the top layer most habitats on Earth. from side to side. to form tabs. Review Vocabulary metabolism: all of the chemical reactions that occur within an organism (p. -

SPAWAR FY18 PMRF Marine Mammal Monitoring

Submitted in Support of the U.S. Navy’s 2018 Annual Marine Species Monitoring Report for the Pacific DISTRIBUTION A. Approved for public release: distribution unlimited. FY18 Annual Report on Pacific Missile Range Facility Marine Mammal Monitoring Cameron R. Martin1, E. Elizabeth Henderson2, Stephen W. Martin1, Tyler A. Helble2, Roanne A. Manzano-Roth2, Brian M. Matsuyama1, and Gabriela C. Alongi1 1 National Marine Mammal Foundation, San Diego, CA 2 Naval Information Warfare Center Pacific, San Diego, CA Final report dated March 5, 2019 Suggested Citation: Martin, C.R., E.E. Henderson, S.W. Martin, T.A. Helble, R.A. Manzano- Roth, B.M. Matsuyama, and G.C. Alongi. (2019). FY18 Annual Report on Pacific Missile Range Facility Marine Mammal Monitoring. Naval Information Warfare Center, Pacific 1 Submitted in Support of the U.S. Navy’s 2018 Annual Marine Species Monitoring Report for the Pacific DISTRIBUTION A. Approved for public release: distribution unlimited. This page intentionally left blank. Submitted in Support of the U.S. Navy’s 2018 Annual Marine Species Monitoring Report for the Pacific DISTRIBUTION A. Approved for public release: distribution unlimited. Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden to Washington Headquarters Service, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington, DC 20503. -

Highly Classified Years 11-12

Highly Classified Years 11-12 Getting Sorted Locate the animals listed below and find out their scientific name. Remember that the scientific name is usually written in italics or is underlined. Common Name Scientific Name (Genus species) A. Javan Gibbon _____________________________________ B. Southern White Rhino _____________________________________ C. Asian Elephant _____________________________________ D. Western Swamp Tortoise _____________________________________ E. Dugite _____________________________________ F. Little Penguin _____________________________________ G. Sumatran Orangutan _____________________________________ H. African Painted Dog _____________________________________ I. Green Tree Frog _____________________________________ J. Nepalese Red Panda _____________________________________ K. Perentie _____________________________________ L. Southern Cassowary _____________________________________ Classify these animals according to the groupings in the tables below and the fol- lowing page (note: only use the LETTER corresponding to each animal, not the common or scientific name) Body Covering Moist Skin Dry Scales Wet Scales Feathers Fur/Hair Distribution Africa Asia Australia Highly Classified Years 11-12 Getting Sorted (continued) Diet (in the wild) Herbivore Carnivore Omnivore Habitat Terrestrial (land dwelling) Arboreal (tree living) Aquatic (water living) Vertebrate Class (only considering 5 basic groupings) Pisces (Fish) Amphibia Reptilia Mammalia Aves (Birds) Despite their similarities, ‘Fish’ are only an informal -

F. Wolves As Special Status Game Mammals

First Draft Update (March 2017) F. Wolves as Special Status Game Mammals In 2009, the Oregon Legislature changed the status of wolves from protected non-game wildlife to a special status game mammal under ORS 496.004 (9). This change was called for in the 2005 Plan and allows ODFW to use existing, stable state and federal funding sources and existing field staff to include wolf management as part of their daily duties. These funding sources include both federal Wildlife Restoration grants (also known as Pittman-Robertson) and fees from the sale of hunting licenses. The status also allows the use of controlled take through hunting and trapping (under two circumstances) in response to management concerns. Note: While in Phase I and II wolves are protected consistent with the direction outlined in the Plan; in Phase III the special status mammal classification allows ODFW use of a range of management tools to advance conservation and responsible management of wolves. The special status mammal classification recognizes the wolf’s distinct history of extirpation and conflict with certain significant human activities as well as its distinct place in human social attitudes based on experiences and myths that span centuries. This classification is based on Oregon’s management successes with respect to other large carnivores (e.g., black bear, cougar) but also recognizes the factors that make the wolf somewhat distinct from other large carnivores. It provides the most options for long term management by retaining, in addition to protective measures, tools such as responsive hunting and trapping when required for management purposes, although these management tools would not be applied in the same manner as under a traditional game mammal or furbearer classification. -

Folk Knowledge of Non-Domestic Mammals Among Ethnic Hungarians in North-Western Romania

NORTH-WESTERN JOURNAL OF ZOOLOGY 9 (2): 383-398 ©NwjZ, Oradea, Romania, 2013 Article No.: 131705 http://biozoojournals.3x.ro/nwjz/index.html Folk knowledge of non-domestic mammals among ethnic Hungarians in North-Western Romania Viktor ULICSNI1,*, Ingvar SVANBERG2 and Zsolt MOLNÁR3 1. Department of Ecology, Faculty of Science and Informatics of the University of Szeged, 6726 Szeged, Közép fasor 52, Hungary. 2. Uppsala Centre for Russian and Eurasian Studies, Uppsala Univerisity, Box 514, 751 20 Uppsala, Sweden. 3. Centre for Ecological Research, Institute of Ecology and Botany, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, 2163 Vácrátót, Hungary. * Correspnding author, V. Ulicsni, E-mail: [email protected] Received: 07. February 2013 / Accepted: 04. April 2013 / Available online: 06. June 2013 / Printed: December 2013 Abstract. Most ethnobiological research on mammals has focused on the domesticated species and largely ignored the wild taxa. We carried out a research among the ethnic Hungarians in Nuşfalău, Romania, to document the local ecological knowledge on mammals. We studied which kinds of local wild mammals the villagers know, which folk taxa they can identify, the names they use for these taxa, and what do they know about the morphological, behavioural and ecological characteristics, as well as the economical impact of these mammals. Twenty persons were interviewed with the aid of colour photographs of 62 mammal species. Five hundred and twenty three individual data on the various folk taxa were thus gathered. The majority of the interviewees were still possessed surprisingly detailed and precise knowledge on the wild species living in their surroundings. They classified the 62 mammal species into 42 folk taxa and grouped them into 11 larger sets. -

Skulls of Alaskan Mammals

Skulls of Alaskan Mammals A Teacher’s Guide Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Wildlife Conservation © 2005 Skulls of Alaskan Mammals A Teacher’s Guide Original Text: Ruth M. Gronquist Revised Text and Activities: Kristen Romanoff Editors: Robin Dublin, Lilly Goodman, Polly Hessing, Mike Taras & Sue Steinacher Reviewers: Jessie Coltrane, Ruth Gronquist, Polly Hessing, Rebecca Kellyhouse & Boyd Porter Layout: Kristen Romanoff, Andy Romanoff & Sue Steinacher Illustrations: Copyright Richard Carstensen, Kathy Hocker & Sue Steinacher Skull Sheets: Adapted from Hall and Kelson. 1959, Ronald Press Company. This revision of the original 1983, Skulls of Alaska Mammals by Ruth Gronquist, Alaska Department of Fish and Game, is made possible with funding from the State Wildlife Grants program. Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Wildlife Conservation © 2005 The Alaska Department of Fish and Game administers all programs and activities free from discrimination based on race, color, national origin, age, sex, religion, marital status, pregnancy, parenthood, or disability. For information on alternative formats for this and other ADF&G publications, please contact the Department of ADA Coordinator at (voice) 907-465-4120, telecommunication device for the deaf (TDD) 1-800-478-3648, or fax 907-465- 6078. Any person who believes she/he has been discriminated against should write to ADF&G, PO Box 25526, Juneau, AK 99802-5526 or OEO, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, DC 20240. Skulls of Alaskan Mammals A Teacher’s Guide 1. Introduction 2. About Skulls 3. Activities A. Skull Detective: Teeth, Eyes & More B. Who’s Related to Whom? C. Drawing Skulls D.