Biography of Alejandro Portes BIOGRAPHY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A S R F 2007 ASA PRESIDENTIAL ADDRESS Frances Fox Piven Can

3285 ASR 1/7/08 10:32 AM Page 1 A Washington, DC 20005-4701 Washington, Suite 700 NW, Avenue York 1307 New (ISSN 0003-1224) American Sociological Review MERICAN S Sociology of Education OCIOLOGICAL A Journal of the American Sociological Association Edited by Barbara Schneider Michigan State University Quarterly, ISSN 0038-0407 R EVIEW SociologyofEducationpublishes papers advancing sociological knowledge about education in its various forms. Among the many issues considered in the journal are the nature and determinants of educational expansion; the relationship VOLUME 73 • NUMBER 1 • FEBRUARY 2008 between education and social mobility in contemporary OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION society; and the implications of diverse ways of organizing schools and schooling for teaching, learning, and human 2007 ASA PRESIDENTIAL ADDRESS development. The journal invites papers that draw on a wide range of methodological approaches that can contribute to a Frances Fox Piven F EBRUARY Can Power from Below Change the World? sociological understanding of these and other educational phenomena. Print subscriptions to ASA journals include online access to the current year’s issues MARGINALIZATION IN GLOBAL CONTEXT at no additional charge through Ingenta,the leading provider of online publishing 2008 V Eileen M. Otis services to academic and professional publishers. Labor and Gender Organization in China Christopher A. Bail 2008 Subscription Rates Symbolic Boundaries in 21 European Countries ASA Members $40 • Student Members $25 • Institutions (print/online) $185, (online only) $170 (Add $20 for subscriptions outside the U.S. or Canada) RELIGION IN SOCIAL LIFE Individual subscribers are required to be ASA members. To join ASA and subscribe at discounted member rates, see www.asanet.org D. -

Embeddedness and Immigration: Notes on the Social Determinants Of

Embeddedness and Immigration: Notes on the Social Determinants of Economic Action Author(s): Alejandro Portes and Julia Sensenbrenner Source: The American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 98, No. 6 (May, 1993), pp. 1320-1350 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2781823 Accessed: 25/02/2010 09:22 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ucpress. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The American Journal of Sociology. http://www.jstor.org Embeddedness and Immigration: Notes on the Social Determinants of Economic Action1 Alejandro Portes and Julia Sensenbrenner Johns Hopkins University This article contributes to the reemerging field of economic sociol- ogy by (1) delving into its classic roots to refine current concepts and (2) using examples from the immigration literature to explore the different forms in which social structures affect economic ac- tion. -

Reflections on a Sociological Career That Integrates Social Science With

SO37-Frontmatter ARI 11 June 2011 11:38 by Harvard University on 07/21/11. For personal use only. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2011.37:1-18. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org SO37CH01-Wilson ARI 1 June 2011 14:22 Reflections on a Sociological Career that Integrates Social Science with Social Policy William Julius Wilson Kennedy School and Department of Sociology, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138; email: [email protected] Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2011. 37:1–18 Keywords First published online as a Review in Advance on race and ethnic relations, urban poverty, social class, affirmative March 1, 2011 action, public policy, public agenda research The Annual Review of Sociology is online at soc.annualreviews.org Abstract by Harvard University on 07/21/11. For personal use only. This article’s doi: This autobiographical essay reflects on my sociological career, high- 10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102510 lighting the integration of sociology with social policy. I discuss the Copyright c 2011 by Annual Reviews. personal, social, and intellectual experiences, ranging from childhood Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2011.37:1-18. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org All rights reserved to adult life, that influenced my pursuit of studies in race and ethnic re- 0360-0572/11/0811-0001$20.00 lations and urban poverty. I then focus on how the academic and public reaction to these studies increased my concerns about the relationship between social science and public policy, as well as my attempts to make my work more accessible to a general audience. In the process, I discuss how the academic awards and honors I received based on these studies enhanced my involvement in the national policy arena. -

SOCIAL CAPITAL: Its Origins and Applications in Modern Sociology

Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1998. 24:1–24 Copyright © 1998 by Annual Reviews. All rights reserved SOCIAL CAPITAL: Its Origins and Applications in Modern Sociology Alejandro Portes Department of Sociology, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 KEY WORDS: social control, family support, networks, sociability ABSTRACT This paper reviews the origins and definitions of social capital in the writings of Bourdieu, Loury, and Coleman, among other authors. It distinguishes four sources of social capital and examines their dynamics. Applications of the concept in the sociological literature emphasize its role in social control, in family support, and in benefits mediated by extrafamilial networks. I provide examples of each of these positive functions. Negative consequences of the same processes also deserve attention for a balanced picture of the forces at play. I review four such consequences and illustrate them with relevant ex- amples. Recent writings on social capital have extended the concept from an individual asset to a feature of communities and even nations. The final sec- tions describe this conceptual stretch and examine its limitations. I argue that, as shorthand for the positive consequences of sociability, social capital has a definite place in sociological theory. However, excessive extensions of the concept may jeopardize its heuristic value. Alejandro Portes: Biographical Sketch Alejandro Portes is professor of sociology at Princeton University and by Swiss Academic Library Consortia on 03/24/09. For personal use only. faculty associate of the Woodrow Wilson School of Public Affairs. He for- Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1998.24:1-24. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org merly taught at Johns Hopkins where he held the John Dewey Chair in Arts and Sciences, Duke University, and the University of Texas-Austin. -

CURRICULUM VITAE (May 2010) Rubén G

CURRICULUM VITAE (May 2010) Rubén G. Rumbaut Present Position: Professor of Sociology 3151 Social Science Plaza E-mail: [email protected] University of California, Irvine http://www.faculty.uci.edu/profile.cfm?faculty_id=4999 Irvine, CA 92697 Personal Information: Place of Birth: La Habana, Cuba Citizenship: U.S. (Naturalization: May 2, 1969) Languages: Spanish and English (fluent in both) Formal Education: 1971-1973 Brandeis University, Waltham, Massachusetts: Ph.D.: 1978 (Sociology) M.A.: 1973 (Sociology) 1969-1971 San Diego State University, San Diego, California: M.A. Program (Sociology) 1965-1969 Washington University, St. Louis, Missouri: B.A.: 1969 (Sociology-Anthropology and Biology) Academic and Professional Appointments: 2002- Professor, Department of Sociology, University of California, Irvine 2002-2006 Co-Director, Center for Research on Immigration, Population, and Public Policy, UCI 2000-2001 Fellow, Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences, Stanford 1997-1998 Visiting Scholar, Russell Sage Foundation, New York City 1993-2002 Professor, Department of Sociology, Michigan State University; and Senior Faculty Associate, Julián Samora Research Institute, and Institute for Public Policy & Social Research, MSU. 1992-1994 Senior Research Fellow, Center for U.S.-Mexican Studies, Univ. of California, San Diego; and Visiting Scholar, Center for Research on Social Organization, University of Michigan 1988-1993 Professor, Department of Sociology, San Diego State University 1985-1988 Associate Professor, Department of Sociology, -

THE HIDDEN ABODE: SOCIOLOGY AS ANALYSIS of the UNEXPECTED* 1999 Presidentialaddress

THE HIDDEN ABODE: SOCIOLOGY AS ANALYSIS OF THE UNEXPECTED* 1999 PresidentialAddress Alejandro Portes PrincetonUniversity Purposive social action has provided the bedrockfor theoretical develop- ments and model building in several social sciences. Since its beginnings, however, sociology has harbored, a "contrarian" vocation based on exam- ining the unrecognized, unintended,and emergentconsequences of goal-ori- ented activity. I present several examples of the sociological practice of bashing myths based on the logic of purposive action and offer a typology of alternative goals, means, and outcomes illustrated by both classic sociologi- cal writings and contemporary research. The multiple contingencies docu- mented by sociologists in the past cautions against attempts to build institu- tions or implementprograms grounded on grand blueprints. The cautionary tale supported by sociological analysis of concealed goals, shifts in mid- course, and unexpectedeffects does not lead, however,to the conclusion that scientific prediction and practical interventionare futile endeavors. It leads instead to an emphasis on the dialectics of social life, and on the need to take into account the definitions of the situation of relevant actors. I offer some illustrations of successful mid-range theories that are based on the analysis of dilemmas in social processes and the importance of sensitivity to the unexpected in the implementationof programmatic interventions. A little while ago, duringone of his pe- Businessin his privateschool was booming, A riodic trips to New YorkCity, I met despiteits steep tuition-unusual for a Third RobertoFernandez Miranda, principal of the Worldcountry. The secret was that his stu- La Luz school in the DominicanRepublic. dents were mostly children of expatriates, not those who had returnedhome, but immi- * Direct all correspondenceto Alejandro Portes, grantsstill living and workingin New York. -

Stratification and Social Inequality Reading List

*DISCLAIMER: Students planning to take the preliminary exam should verify with the graduate coordinator that the posted reading list is the most up to date version before they begin studying. Stratification Preliminary Exam Reading List—Unformatted Draft Revised for 2016-2017 Note: Within each section (Foundations, Race, Class, Gender, and Intersectionality), there are readings that cover to some degree the following social institutions and other sociological concepts: family, education, sexuality, comparative/global, government/the state, attitudinal research, religion, and collective behavior. FOUNDATIONS IN STRATIFICATION Note: The Foundations section of this list covers the following: Marx, Weber, Durkheim, neo- Marxists, neo-Weberians, neo-Durkheimians, the roots of American sociology/stratification, articles/books that deal broadly in the sociological study of stratification, and the history of stratification and inequality. Block, Fred and Margaret R. Somers. 2014. The Power of Market Fundamentalism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Cox, Oliver C. [1948] 1959. Caste, Class, & Race: A Study in Social Dynamics. New York: Monthly Review Press. (Chapters 14, 15, 19, 21, 23, 25) Dahrendorf, Ralf. 2014. “Class and Class Conflict in Industrial Society.” Pp. 143–49 in Social Stratification: Class, Race, and Gender in Sociological Perspective, edited by D. B. Grusky. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. Davis, Kingsley and Wilbert E. Moore. 1945. “Some Principles of Stratification.” American Sociological Review 10(2):242–49. Domhoff, William. 2014. “Who Rules America?” Pp. 297–302 in Social Stratification: Class, Race, and Gender in Sociological Perspective, edited by D. B. Grusky. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. Durkheim, Emile. 2014. “The Division of Labor in Society.” Pp. 217–22 in Social Stratification: Class, Race, and Gender in Sociological Perspective, edited by D. -

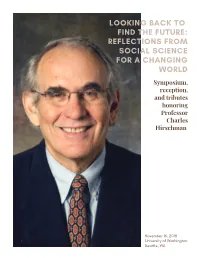

Symposium, Reception, and Tributes Honoring Professor Charles Hirschman

LOOKING BACK TO FIND THE FUTURE: REFLECTIONS FROM SOCIAL SCIENCE FOR A CHANGING WORLD Symposium, reception, and tributes honoring Professor Charles Hirschman November 16, 2018 University of Washington Seattle, WA Compiled by the Center for Studies in Demography & Ecology (CSDE) Contents Symposium and Reception Program ........................................................................................ 1 Symposium Panels ..................................................................................................................... 4 Welcome ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 Robert Stacey ............................................................................................................................................. 6 American Social Science in the Asian Century: What Role for Area Studies? ...................................... 7 Patrick Heuveline ...................................................................................................................................... 8 Maria-Giovanna Merli ............................................................................................................................ 13 Understanding and Responding to Rising Inequality ............................................................................. 17 Marta Tienda........................................................................................................................................... -

SOCIAL CAPITAL: Its Origins and Applications in Modern Sociology

P1: H September 25, 1998 10:31 Annual Reviews AR064-00 SO24-FrontisP Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1998.24:1-24. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org Access provided by Stanford University - Main Campus Robert Crown Law Library on 03/10/17. For personal use only. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1998. 24:1–24 Copyright © 1998 by Annual Reviews. All rights reserved SOCIAL CAPITAL: Its Origins and Applications in Modern Sociology Alejandro Portes Department of Sociology, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 KEY WORDS: social control, family support, networks, sociability ABSTRACT This paper reviews the origins and definitions of social capital in the writings of Bourdieu, Loury, and Coleman, among other authors. It distinguishes four sources of social capital and examines their dynamics. Applications of the concept in the sociological literature emphasize its role in social control, in family support, and in benefits mediated by extrafamilial networks. I provide examples of each of these positive functions. Negative consequences of the same processes also deserve attention for a balanced picture of the forces at play. I review four such consequences and illustrate them with relevant ex- amples. Recent writings on social capital have extended the concept from an individual asset to a feature of communities and even nations. The final sec- tions describe this conceptual stretch and examine its limitations. I argue that, as shorthand for the positive consequences of sociability, social capital has a definite place in sociological theory. However, excessive extensions of the concept may jeopardize its heuristic value. Alejandro Portes: Biographical Sketch Alejandro Portes is professor of sociology at Princeton University and Annu. -

Douglas S. Massey Curriculum Vitae December 3, 2020

Douglas S. Massey Curriculum Vitae December 3, 2020 Address: Office of Population Research Princeton University Wallace Hall Princeton, NJ 08544 [email protected] Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0109-522X Birth: Born October 5, 1952 in Olympia, Washington, USA Citizenship: Citizen and Resident of the United States Education: Ph.D., Sociology, Princeton University, 1978 M.A., Sociology, Princeton University, 1977 B.A., Magna Cum Laude in Sociology-Anthropology, Psychology, and Spanish, Western Washington University, 1974 Honorary Master in Arts and Sciences, Honoris Causa, University Pennsylvania, 1985. Degrees: Doctor of Social Science Honoris Causa, Ohio State University, 2012 Languages: Fluent in Spanish Employment: (9/05-present) Henry G. Bryant Professor of Sociology and Public Affairs, Princeton University (7/03- 8/05) Professor of Sociology and Public Policy, Princeton University (7/94-6/03) Dorothy Swaine Thomas Professor, Department of Sociology, Graduate Group in Demography, and Lauder Program in International Studies, University of Pennsylvania (7/90-6/94) Professor, Irving B. Harris School of Public Policy Studies, University of Chicago (7/87-6/94) Professor, Department of Sociology, University of Chicago (7/85-7/87) Associate Professor, Department of Sociology and Graduate Group in Demography, University of Pennsylvania (9/80-7/85) Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology and Graduate Group in Demography, University of Pennsylvania (9/79-9/80) NSF Postdoctoral Fellow, Graduate Group in Demography, University of California at Berkeley (1/79-6/79) Lecturer, Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, Princeton University (9/78-9/79) Research Associate, Office of Population Research, Princeton University Major Fields: Demography, Urban Sociology, Stratification, Social Research Methods, Latin American Studies, Race/Ethnic Relations, Biosociology, Immigration Honors and Named Phi Beta Kappa Visiting Scholar, 2020-2021 Awards: Academia Europaea, elected member 2018-present Bronislaw Malinowski Award 2018. -

Alejandro Portes' Sociological

Alejandro Portes’ Sociological by Viviana A. Zelizer Princeton University “[P]roblems with which inquiry into social subject and matter is concerned must, if they satisfy the conditions of scientific method, (1) grow out of actual social tensions, needs, ‘troubles’; (2) have their subject-matter determined by the conditions that are material means of bringing about a unified situation, and (3) be related to some hypothesis, which is a plan and policy for existential resolution of the conflicting social situation.” (From The Philosophy of John Dewey edited by John J. McDermott, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981, p. 409). These words from John Dewey’s The Quest for Certainty lay out Dewey’s program for social science. Freely translated, Dewey is telling social scientists, first: ground your work in genuine social problems; second: study causes and effects that can make a difference; third, proceed from hypotheses bearing on connections between problems and their possible resolutions. Unwittingly or otherwise, Alejandro Portes, former John Dewey Professor at The Johns Hopkins University has fulfilled Dewey’s program brilliantly. Portes, now Professor of Sociology at Princeton University and 1998-99 President of the American Sociological Association has consistently sought out problematic features of modem social life, especially those he has experienced at first hand. He has brought exceptional clarity to the explanation of social processes. And he has never abandoned the search for concrete paths to social improvement. Anyone who meets Portes in his orderly office at Princeton immediately recognizes the richness, rigor, wisdom, and personal significance of his passionate commitment to social science. Together with his wife, the effervescent Patricia Fernandez-Kelly (herself a formidable presence in the study of immigration, work, and family in Mexico and the United States), Portes has contributed to a renaissance of Latin American and Latino studies at Princeton. -

1 Marta Tienda Curriculum Vitae September 2020 ADDRESS

Marta Tienda Curriculum Vitae September 2020 ADDRESS Office of Population Research, Princeton University 184 Wallace Hall Princeton, New Jersey 08544-2091 Telephone: (609) 258-1753 Fax: (609) 258-1039 e-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION 1968-72 Michigan State University, B.A., Spanish (Education) Honors College Magna Cum Laude 1972-77 The University of Texas at Austin M.A., Sociology, 1975 Ph.D., Sociology, 1977 PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Current Positions Princeton University, 1997 - • Maurice P. During ’22 Professor in Demographic Studies, 1999 – • Professor of Sociology and Public Affairs, 1997 - • Research Associate, Office of Population Research, 1997 - Past Positions Margaret Olivia Sage Visiting Scholar, Russell Sage Foundation 2015-2016 Visiting Scholar, NYU Center for Advanced Social Science Research, 2010-11 Distinguished Visiting Professor, Brown University, January - June, 2007 Visiting Scholar, The Rockefeller Foundation, 2006 – 2007 Ralph Lewis Professor of Sociology, University of Chicago, September 1994 - 1997 • Professor of Sociology, University of Chicago, October 1987 - 1994 • Research Associate, Population Research Center and Ogburn-Stouffer Center, 1987 - 1997 Visiting Professor, Department of Sociology, Stanford University, January-June, 1987 Professor, Department of Rural Sociology, University of Wisconsin-Madison 1983 - 1989 • Associate Professor, 1980 - 1983 • Assistant Professor, 1976 - 1980 Assistant to the Director, Special Programs, Michigan Cooperative Extension Service, March - August 1972 ADMINISTRATIVE EXPERIENCE Founding Director, Program in Latino Studies, Princeton University, 2009 - 2018 Director, Office of Population Research, Princeton University, 1998 - 2002 Director of Graduate Studies, Office of Population Research, 2008- 2010; 2011-2015 Faculty Chair PhD Program, Woodrow Wilson School, 2009-2010 Chair, Department of Sociology, University of Chicago, 1994 – 1997 1 Biography Diane O’Connell.