Did the Dutch Elections Go Wrong for Groenlinks?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Green Policies Are About Our Entire Way of Life”

“Green Policies Are about Our Entire Way of Life” Article by Inés Sabanés August 31, 2021 The Covid-19 pandemic is the latest in a string of crises Spain has faced in recent years, which have left the country weakened and many worried about its future. With elections on the horizon, Member of the Spanish Parliament Inés Sabanés explains how an all-encompassing Green vision can transform every aspect of society, and why Europe has the potential to help Spain overcome many of its difficulties. Green European Journal: From the perspective of the Greens (Verdes Equo), what are the key political issues facing Spain in 2021? Inés Sabanés: The pandemic has reset political priorities at both the Spanish and European levels. Three fundamental issues stick out; they were important during the 2021 Madrid elections and are present throughout our daily political life. First is the economic and social recovery: in response to the crisis caused by the pandemic but also in connection to the climate emergency. The distribution of projects arising from European funds needs to bring us out of this crisis through a fundamental structural change to the way our country works. Spain today is too susceptible to crises – our economy is overdependent on tourism for example – and needs to build its future on a more solid, productive, and better developed economic model. The second major issue is the rise of the far right. Frequent elections have been a fundamental error and a lack of consensus between parties in government has led to a rise in the number of far-right members of parliament. -

En Zo Werd Er De Afgelopen Vier Jaar Gestemd

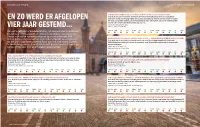

UITKERINGSGERECHTIGDEN TWEEDE KAMER VERKIEZINGEN EEN INKOMENSAANVULLING VOOR MENSEN MET EEN MEDISCHE URENBEPERKING Deze motie beoogde te bereiken dat mensen met een beperking/handicap die naar hun maximale EN ZO WERD ER AFGELOPEN vermogen werken, een toeslag krijgen die los staat van eventueel inkomen van een partner of ouders. Dit omdat zij vanwege die medische urenbeperking dus maar een beperkt aantal uren kunnen werken en zodoende onvoldoende inkomen kunnen genereren. Stemdatum: 24 september 2019 VIER JAAR GESTEMD… Indiener: Jasper van Dijk (SP) Van extra geld voor armoedebestrijding, tot aanpassingen in de Wajong. 50PLUS CDA CU D66 DENK FvD GL PvdA PvdD PVV SGP SP VVD De afgelopen vier jaar heeft de Tweede Kamer kunnen stemmen over diverse voorstellen ter verbetering van de sociale zekerheid. FNV Uitkeringsgerechtigden heeft er acht moties uitgepikt. Groen betekent AANPASSEN WETSVOORSTEL WAJONG OM DE REGELS TE HARMONISEREN ZONDER VERSLECHTERING Deze motie was bedoeld om het alternatief zoals opgesteld door belangenorganisaties (onder wie dat een partij voor heeft gestemd. Rood was een stem tegen. Duidelijk FNV Uitkeringsgerechtigden) in de wet te verwerken, zodat de nadelige gevolgen van de harmonisatie te zien is dat geen van de moties het heeft gehaald omdat de regerings- worden voorkomen. partijen (VVD, CDA, D66 en CU) steeds tegenstemden. Stemdatum: 30 oktober 2019 Indieners: PvdA, GL, SP en 50Plus 50PLUS CDA CU D66 DENK FvD GL PvdA PvdD PVV SGP SP VVD EEN AANGESCHERPT AFSLUITINGSBELEID VOOR DRINKWATER EN WIFI Deze motie was opgesteld om naast gas en elektriciteit ook drinkwater en internet op te nemen als basis- voorziening. Dit om te voorkomen dat mensen met een betalingsachterstand in een onleefbare situatie EXTRA GELD OM DE GEVOLGEN VAN ARMOEDE ONDER KINDEREN TE BESTRIJDEN belanden als deze voorzieningen worden afgesloten. -

I&O-Zetelpeiling 15 Maart 2021

Rapport I&O-Zetelpeiling 15 maart 2021 VVD levert verder in; D66 stijgt door; Volt en Ja21 maken goede kans Colofon Maart peiling #2 I&O Research Uitgave I&O Research Piet Heinkade 55 1019 GM Amsterdam Rapportnummer 2021/69 Datum maart 2021 Auteurs Peter Kanne Milan Driessen Het overnemen uit deze publicatie is toegestaan, mits de bron (I&O Research) duidelijk wordt vermeld. 15 maart 2021 2 van 15 Inhoudsopgave Belangrijkste uitkomsten _____________________________________________________________________ 4 1 I&O-zetelpeiling: VVD levert verder in ________________________________________________ 7 VVD levert verder in, D66 stijgt door _______________________ 7 Wie verliest aan wie en waarom? _________________________ 9 Aandeel zwevende kiezers _____________________________ 11 Partij van tweede (of derde) voorkeur_______________________ 12 Stemgedrag 2021 vs. stemgedrag 2017 ______________________ 13 2 Onderzoeksverantwoording _________________________________________________________ 14 15 maart 2021 3 van 15 Belangrijkste uitkomsten VVD levert verder in; D66 stijgt door; Volt en Ja21 maken goede kans In de meest recente I&O-zetelpeiling – die liep van vrijdag 12 tot maandagochtend 15 maart – zien we de VVD verder inleveren (van 36 naar 33 zetels) en D66 verder stijgen (van 16 naar 19 zetels). Bij peilingen (steekproefonderzoek) moet rekening gehouden worden met onnauwkeurigheids- marges. Voor VVD (21,0%, marge 1,6%) en D66 (11,8%, marge 1,3%) zijn dat (ruim) 2 zetels. De verschuiving voor D66 is statistisch significant, die voor VVD en PvdA zijn dat nipt. Als we naar deze zetelpeiling kijken – 2 dagen voor de verkiezingen – valt op hoezeer hij lijkt op de uitslag van de Tweede Kamerverkiezingen van 2017. Van de winst die de VVD boekte in de coronacrisis is niets over: nu 33 zetels, vier jaar geleden ook 33 zetels. -

The Notion of Religion in Election Manifestos of Populist and Nationalist Parties in Germany and the Netherlands

religions Article Religion, Populism and Politics: The Notion of Religion in Election Manifestos of Populist and Nationalist Parties in Germany and The Netherlands Leon van den Broeke 1,2,* and Katharina Kunter 3,* 1 Faculty of Religion and Theology, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, 1081 HV Amsterdam, The Netherlands 2 Department of the Centre for Church and Mission in the West, Theological University, 8261 GS Kampen, The Netherlands 3 Faculty of Theology, University of Helsinki, 00014 Helsinki, Finland * Correspondence: [email protected] (L.v.d.B.); katharina.kunter@helsinki.fi (K.K.) Abstract: This article is about the way that the notion of religion is understood and used in election manifestos of populist and nationalist right-wing political parties in Germany and the Netherlands between 2002 and 2021. In order to pursue such enquiry, a discourse on the nature of manifestos of political parties in general and election manifestos specifically is required. Election manifestos are important socio-scientific and historical sources. The central question that this article poses is how the notion of religion is included in the election manifestos of three Dutch (LPF, PVV, and FvD) and one German (AfD) populist and nationalist parties, and what this inclusion reveals about the connection between religion and populist parties. Religious keywords in the election manifestos of said political parties are researched and discussed. It leads to the conclusion that the notion of religion is not central to these political parties, unless it is framed as a stand against Islam. Therefore, these parties defend Citation: van den Broeke, Leon, and the Jewish-Christian-humanistic nature of the country encompassing the separation of ‘church’ or Katharina Kunter. -

The Future of Europe - Perspectives Debate Was Moderated by Political Journalist Fernando from Spain Berlin

sociologist and expert from the EQUO Foundation. The The Future of Europe - Perspectives debate was moderated by political journalist Fernando from Spain Berlin. The conclusions of the seminar are presented below, after an introduction to the Spanish political system and the particularities of the economic crisis in Spain. The European Union is in The Spanish Party Political System a vulnerable situation. The project that started half a Spain is currently governed by the conservative party century ago is now (Partido Popular - PP) that holds an absolute majority staggering. (186 of 350 parliamentary seats since the 2011 elections). The landslide electoral win of the conservatives was the While its primary objective of ensuring peace on the result of a massive protest vote against the Socialist continent has been a success, subsequent Party (PSOE) for its inability to address the economic expectations of greater political integration beyond a crisis after 8 years in power. mere common market are not accomplished. The EU project itself is now in question, not only from the The Spanish party system was created with the intention outside, where the markets doubt and test the to provide on the one hand political stability to the young viability of the Euro - its economic flagship, but also democracy trough a nation-wide two-party system (the from within Europe whose citizens are beginning to electoral system making it virtually impossible for any doubt the direction of the project and the legitimacy other party except the PP and PSOE to govern) and on the of EU policies. Even in countries traditionally pro- other hand to allow the representation of regional European like Spain or Greece, where in past times political forces in the chamber of deputies, as the of dictatorship the EU was seen as the ultimate electoral system favours parties that concentrate big democratic achievement, this once unconditional amounts of votes in a specific region. -

Green Parties and Elections to the European Parliament, 1979–2019 Green Par Elections

Chapter 1 Green Parties and Elections, 1979–2019 Green parties and elections to the European Parliament, 1979–2019 Wolfgang Rüdig Introduction The history of green parties in Europe is closely intertwined with the history of elections to the European Parliament. When the first direct elections to the European Parliament took place in June 1979, the development of green parties in Europe was still in its infancy. Only in Belgium and the UK had green parties been formed that took part in these elections; but ecological lists, which were the pre- decessors of green parties, competed in other countries. Despite not winning representation, the German Greens were particularly influ- enced by the 1979 European elections. Five years later, most partic- ipating countries had seen the formation of national green parties, and the first Green MEPs from Belgium and Germany were elected. Green parties have been represented continuously in the European Parliament since 1984. Subsequent years saw Greens from many other countries joining their Belgian and German colleagues in the Euro- pean Parliament. European elections continued to be important for party formation in new EU member countries. In the 1980s it was the South European countries (Greece, Portugal and Spain), following 4 GREENS FOR A BETTER EUROPE their successful transition to democracies, that became members. Green parties did not have a strong role in their national party systems, and European elections became an important focus for party develop- ment. In the 1990s it was the turn of Austria, Finland and Sweden to join; green parties were already well established in all three nations and provided ongoing support for Greens in the European Parliament. -

JA21 VERKIEZINGSPROGRAMMA 2021-2025 Het Juiste Antwoord VOORWOORD

JA21 VERKIEZINGSPROGRAMMA 2021-2025 Het Juiste Antwoord VOORWOORD Net als velen van u zou ik nergens liever willen leven dan hier. Ons mooie land heeft een gigantisch potentieel. We zijn innovatief, nuchter, hardwer- kend, trots op wie we zijn en gezegend met een indrukwekkende geschie- denis en een gezonde handelsgeest. Een Nederland dat Nederland durft te zijn is tot ongekende prestaties in staat. Al sinds de komst van Pim Fortuyn in 2002 laten miljoenen kiezers weten dat het op de grote terreinen van misdaad, migratie, het functioneren van de publieke sector en Europa anders moet. Nederland zal in een uitdijend en oncontroleerbaar Europa meer voor zichzelf moeten kiezen en vertrouwen en macht moeten terugleggen bij de kiezer. Maar keer op keer krijgen rechtse kiezers geen waar voor hun stem. Wie rechts stemt krijgt daar immigratierecords, een steeds verder uitdijende overheid, stijgende lasten, een verstikkend ondernemersklimaat, afschaffing van het referendum en een onbetaalbaar en irrationeel klimaatbeleid voor terug die ten koste gaan van onze welvaart en ons woongenot. Ons programma is een realistische conservatief-liberale koers voor ieder- een die de schouders onder Nederland wil zetten. Positieve keuzes voor een welvarender, veiliger en herkenbaarder land waarin we criminaliteit keihard aanpakken, behouden wat ons bindt en macht terughalen uit Europa. Met een overheid die er voor de burgers is en goed weet wat ze wel, maar ook juist niet moet doen. Een land waarin we hart hebben voor wie niet kan, maar hard zullen zijn voor wie niet wil. Wij zijn er klaar voor. Samen met onze geweldige fracties in de Eerste Kamer, het Europees Parlement en de Amsterdamse gemeenteraad én met onze vertegenwoordigers in de Provinciale Staten zullen wij na 17 maart met grote trots ook uw stem in de Tweede Kamer gaan vertegenwoordigen. -

How to Choose a Political Party

FastFACTS How to Choose a Political Party When you sign up to vote, you can join a political party. A political party is a group of people who share the same ideas about how the government should be run and what it should do. They work together to win elections. You can also choose not to join any of the political parties and still be a voter. There is no cost to join a party. How to choose a political party: • Choose a political party that has the same general views you do. For example, some political parties think that government should No Party Preference do more for people. Others feel that government should make it If you do not want to register easier for people to do things for themselves. with a political party (you • If you do not want to join a political party, mark that box on your want to be “independent” voter registration form. This is called “no party preference.” Know of any political party), mark that if you do, you may have limited choices for party candidates in “I do not want to register Presidential primary elections. with a political party” on the registration form. In • You can change your political party registration at any time. Just fill California, you can still out a new voter registration form and check a different party box. vote for any candidate in The deadline to change your party is 15 days before the election. a primary election, except If you are not registered with a political party and for Presidential candidates. -

Green Party Constitution 2015

Green Party Constitution 2015 (Following the Annual Convention 28 March 2015) Table of Contents 1. Name 2. Principles o 2.1 Basic Philosophy o 2.2 Socio-economic o 2.3 Political 3. Objective 4. Membership 5. Organisation o 5.1 Dail Constituency Groups o 5.2 Regional Groups o 5.3 Policy Council o 5.4 Standing Committees o 5.5 Executive Committee: Tasks o 5.6 Executive Committee: Composition o 5.7 Party Leader o 5.8 The Dail Party o 5.9 Appeals Committee o 5.10 Cathaoirleach 6. Decision-making and Policy Development 7. National Conventions 8. Finance 9. Public Representatives 10. Revision of Constitution and Standing Orders 11. Operative Date and 12. Transition INDEX 1. NAME The name shall be the Green Party - Comhaontas Glas hereinafter referred to as the Party. 2. PRINCIPLES In these principles we assert the interdependence of all life, and the role of the Green movement in establishing appropriate relationships in this web of interdependence. While respecting the human person, we recognise and celebrate our interdependence with other species. We oppose the destructive processes which are destroying our planet. We favour a balanced and sustainable system of production and utilisation of resources, keeping account of real costs. The task before us is to transform the vision of continued viable life on earth into reality. 2.1 Basic Philosophy 2.1.1 The impact of society on the environment should not be ecologically disruptive. 2.1.2 Conservation of resources is vital to a sustainable society. 2.1.3 We have the responsibility to pass the Earth on to our successors in a fit and healthy state. -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

Professionalization of Green Parties?

Professionalization of Green parties? Analyzing and explaining changes in the external political approach of the Dutch political party GroenLinks Lotte Melenhorst (0712019) Supervisor: Dr. A. S. Zaslove 5 September 2012 Abstract There is a relatively small body of research regarding the ideological and organizational changes of Green parties. What has been lacking so far is an analysis of the way Green parties present them- selves to the outside world, which is especially interesting because it can be expected to strongly influence the image of these parties. The project shows that the Dutch Green party ‘GroenLinks’ has become more professional regarding their ‘external political approach’ – regarding ideological, or- ganizational as well as strategic presentation – during their 20 years of existence. This research pro- ject challenges the core idea of the so-called ‘threshold-approach’, that major organizational changes appear when a party is getting into government. What turns out to be at least as interesting is the ‘anticipatory’ adaptations parties go through once they have formulated government participation as an important party goal. Until now, scholars have felt that Green parties are transforming, but they have not been able to point at the core of the changes that have taken place. Organizational and ideological changes have been investigated separately, whereas in the case of Green parties organi- zation and ideology are closely interrelated. In this thesis it is argued that the external political ap- proach of GroenLinks, which used to be a typical New Left Green party but that lacks governmental experience, has become more professional, due to initiatives of various within-party actors who of- ten responded to developments outside the party. -

The Electoral Geography of European Radical Left Parties Since 1990

‘Red Belts’ anywhere? The electoral geography of European radical left parties since 1990 Petar Nikolaev Bankov, BA, MSc Submitted in the fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Social and Political Sciences College of Social Sciences University of Glasgow January 2020 Abstract European radical left parties (RLPs) are on the rise across Europe. Since 1990 they became an integral part of the party systems across the continent and enjoy an increased level of government participation and policy clout. The main source for this improved position is their increasing electoral support in the past three decades, underpinned by a diversity of electoral geographies. Understood as the patterns of territorial distribution of electoral support across electoral units, the electoral geographies are important, as they indicate the effects of the socio-economic and political changes in Europe on these parties. This thesis studies the sources of the electoral geographies of European RLPs since 1990. The existing literature on these parties highlighted the importance of their electoral geographies for understanding their electoral and governmental experiences. Yet, to this date, it lacks systematic research on these territorial distributions of electoral support in their own right. Such research is important also for the general literature on the spatial distribution of electoral performance. In particular, these works paid limited attention to the relevance of their theories for individual political parties, as they