The 21St Century As an Age of Advancement with the Rest of Asia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Internationalization of the Japanese Yen

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Macroeconomic Linkage: Savings, Exchange Rates, and Capital Flows, NBER-EASE Volume 3 Volume Author/Editor: Takatoshi Ito and Anne Krueger, editors Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-38669-4 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/ito_94-1 Conference Date: June 17-19, 1992 Publication Date: January 1994 Chapter Title: On the Internationalization of the Japanese Yen Chapter Author: Hiroo Taguchi Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c8538 Chapter pages in book: (p. 335 - 357) 13 On the Internationalization of the Japanese Yen Hiroo Taguchi The internationalization of the yen is a widely discussed topic, among not only economists but also journalists and even politicians. Although various ideas are discussed under this heading, three are the focus of attention: First, and the most narrow, is the use of yen by nonresidents. Second is the possibility of Asian economies forming an economic bloc with Japan and the yen at the center. Third, is the possibility that the yen could serve as a nominal anchor for Asian countries, resembling the role played by the deutsche mark in the Euro- pean Monetary System (EMS). Sections 13.1-13.3 of this paper try to give a broad overview of the key facts concerning the three topics, above. The remaining sections discuss the international role the yen could play, particularly in Asia. 13.1 The Yen as an Invoicing Currency Following the transition to a floating exchange rate regime, the percentage of Japan’s exports denominated in yen rose sharply in the early 1970s and con- tinued to rise to reach nearly 40 percent in the mid- 1980s, a level since main- tained (table 13.1). -

Sogo Shosha in Mass Procurement System of Resource Japan’S Develop-And-Import Scheme of Iron Ore in the 1960S*

Revised on: 16/01/2009 The Role of Sogo Shosha in Mass Procurement System of Resource Japan’s Develop-and-Import Scheme of Iron Ore in the 1960s* Akira Tanaka** Faculty of Economics Nagoya City University 1 Yamanohata, Mizuho-cho, Mizuho-ku, Nagoya, 467-8501 Japan Tel: (+81) 52-872-5731 Fax: (+81)52-871-9429 E-mail: [email protected] Keywords: sogo shosha, Japan’s rapid economic growth, mineral resource, transactional relationships Acknowledgement: This work was supported by Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT)’s Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) #16730182, 2004-05, Grant-in-Aid for Science (C) #18530265, 2006-08, and the presidential grant, Nagoya City University, D-7, 2004. * This article is a revised version of Oikonomika, 44(3&4), 171-194, 2008. I am grateful for all the comments on the old version, including from Dr. Yue Wang and Prof. Thomas W. Roehl. ** Akira Tanaka is with Nagoya City University, Nagoya, Japan (email: [email protected]; phone: +81-52-872-5731; fax: +81-52-871-9429). 1 Revised on: 16/01/2009 The Role of Sogo Shosha in Mass Procurement System of Resource: Japan’s Develop-and-Import of Iron Ore in the 1960s Abstract This paper analyzes the role of sogo shosha (Japanese general trading companies) in the develop-and-import scheme of iron ore during the days of post-war high economic growth, and seeks the reasons behind the establishment of sogo shosha’s oligopolistic structure during this period. In the 1960s, with rapid growth in the demand for iron ore, there was a high level of demand for large-scale develop-and-import projects of iron ore from distant locations such as Australia. -

The System of Trade Between Japan and the East European Countries, Including the Soviet Union

THE SYSTEM OF TRADE BETWEEN JAPAN AND THE EAST EUROPEAN COUNTRIES, INCLUDING THE SOVIET UNION YATARO TERADA* INTRODUCTION Poor in natural resources, Japan has long been dependent on overseas supply for most of her raw material and fuel requirements. While imports of raw materials and fuel by the United States and West Germany in 197o accounted respectively for 14 per cent and 22 per cent of their total imports, Japan's imports of raw materials and fuel in the same year amounted to about 59 per cent of her total imports. In addition, Japan depends on imports from foreign countries for ioo per cent of her wool, raw cotton, and nickel; 98 per cent of her petroleum; 95 per cent of her iron ores; and 55 per cent of her industrial coal. Such being the case, one of the guiding principles in Japan's foreign trade policy has been to expand trade with any country, regardless of its political system. Japan was plagued by a gap between her economic growth and her international balance of payments until the mid-i96o's and, in order to improve this situation, promotion of exports was given highest priority. Thus, efforts have been made to expand trade with the Soviet Union and East European countries on a commercial basis. After the resumption of private foreign trade in 1949, trade between Japan and the Soviet Union and East European countries was conducted at a low level for some time. However, since the conclusion of a treaty of commerce and an agree- ment on trade and payment with the Soviet Union in 1957, and the conclusion of treaties of commerce with Poland and Czechoslovakia in 1958 and 1959, Japan's trade with Eastern Europe has increased yearly. -

Institutions, Competition, and Capital Market Integration in Japan

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES INSTITUTIONS, COMPETITION, AND CAPITAL MARKET INTEGRATION IN JAPAN Kris J. Mitchener Mari Ohnuki Working Paper 14090 http://www.nber.org/papers/w14090 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 June 2008 A version of this paper is forthcoming in the Journal of Economic History. We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Ronald Choi, Jennifer Combs, Noriko Furuya, Keiko Suzuki, and Genna Tan for help in assembling the data. Mitchener would also like to thank the Institute for Monetary and Economic Studies at the Bank of Japan for its hospitality and generous research support while serving as a visiting scholar at the Institute in 2006, and the Dean Witter Foundation for additional financial support. We also thank conference participants at the BETA Workshop in Strasbourg, France and seminar participants at the Bank of Japan for comments and suggestions. The views presented in this paper are solely those of the authors, and do not necessarily represent those of the Bank of Japan, its staff, or the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2008 by Kris J. Mitchener and Mari Ohnuki. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Institutions, Competition, and Capital Market Integration in Japan Kris J. Mitchener and Mari Ohnuki NBER Working Paper No. -

CSR for ITOCHU Corporation (PDF 780KB)

CSR for ITOCHU Corporation ITOCHU Corporation is pursuing multifacetted corporate activities in various regions of the world and a wide range of fields, and as such, ITOCHU is well aware of how significant its impact on society is. We believe that corporate social responsibility (CSR) lies in corporate thought and action on the question of how to play a role in building sustainable societies through business activities. We also believe that our mission is to fulfill our Corporate Social Responsibility as a global enterprise, always working from the viewpoint of whether we are contributing to the countries of the world and to society. ITOCHU Group Corporate Message ITOCHU founder Chubei Itoh first launched a wholesale linen business in 1858. For more than 150 years since, ITOCHU has passed down the spirit of sampo yoshi (good for the buyer, seller and society), a management philosophy embraced by Ohmi merchants that is the source of its CSR thinking today. After considering ways to demonstrate its commitment to society as an international corporation and to put this commitment into practice, in 1992 ITOCHU formulated “Committed to the Global Good” as a corporate philosophy. The conceptual framework for this philosophy was reorganized in 2009. In order for all employees to properly understand the responsibility that the ITOCHU Group is charged with fulfilling for society and to make this philosophy an integral part of actions everyday, its core element, “Committed to the Global Good,” was set as the ITOCHU Mission for the entire ITOCHU Group. Accompanying this is a new set of five values, called the ITOCHU Values, considered vital for enabling each employee to fulfill their role in realizing the ITOCHU Mission. -

Financial Section 2014

For the Year ended March 31, 2014 ended March For the Year Financial Section 2014 Financial Section 2014 ITOCHU Corporation ITOCHU Corporation FINANCIAL SECTION 2014 1 Contents 2 Six-year Summary (U.S. GAAP) 3 Summary (IFRS) 4 Management’s Discussion and Analysis of Financial Condition and Results of Operations 32 Consolidated Statement of Financial Position 34 Consolidated Statement of Comprehensive Income 36 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 37 Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 38 Notes to Consolidated Financial Statements 112 Independent Auditor’s Report 114 Supplementary Explanation 115 Management Internal Control Report (Translation) 116 Independent Auditor’s Report (filed under the Financial Instruments and Exchange Act of Japan) Forward-Looking Statements This Annual Report contains forward-looking statements regarding ITOCHU Corporation’s corporate plans, strategies, forecasts, and other statements that are not historical facts. They are based on current expectations, estimates, forecasts and projections about the industries in which ITOCHU Corporation operates. As the expectations, estimates, forecasts and projections are subject to a number of risks, uncertainties and assumptions, including without limitation, changes in economic conditions; fluctuations in currency exchange rates; changes in the competitive environment; the outcome of pending and future litigation; and the continued availability of financing; financial instruments and financial resources, they may cause actual results to differ materially from those presented in such forward-looking statements. ITOCHU Corporation, therefore, wishes to caution that readers should not place undue reliance on forward-looking statements, and, further that ITOCHU Corporation undertakes no obligation to update any forward- looking statements as a result of new information, future events or other developments. -

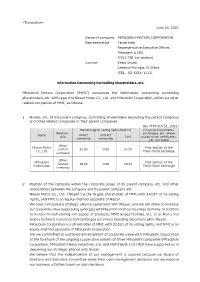

<Translation> June 24, 2021 Name of Company

<Translation> June 24, 2021 Name of company: MITSUBISHI MOTORS CORPORATION Representative: Takao Kato Representative Executive Officer, President & CEO (7211 TSE 1st section) Contact: Keiko Sasaki General Manager, IR Office (TEL.03-3456-1111) Information Concerning Controlling Shareholders, etc. Mitsubishi Motors Corporation (“MMC”) announces the information concerning controlling shareholders, etc. with regard to Nissan Motor Co., Ltd. and Mitsubishi Corporation, which are other related companies of MMC, as follows: 1 Names, etc. of the parent company, controlling shareholders (excluding the parent company) and other related companies or their parent companies (As of March 31, 2021) Percentage of voting rights held (%) Financial instruments Relation- exchanges, etc. where Name Direct Indirect ship Total issued share certificates, ownership ownership etc. are listed Other Nissan Motor First Section of the related 34.03 0.00 34.03 Co., Ltd. Tokyo Stock Exchange company Other Mitsubishi First Section of the related 20.02 0.00 20.02 Corporation Tokyo Stock Exchange company 2 Position of the company within the corporate group of its parent company, etc. and other relationships between the company and its parent company, etc. Nissan Motor Co., Ltd. (“Nissan”) is the largest shareholder of MMC with 34.03% of its voting rights, and MMC is an equity-method associate of Nissan. We have concluded a strategic alliance agreement with Nissan, and we will strive to increase our corporate value by pursuing synergies with Nissan in all of our business domains. In addition to mutual manufacturing and supply of products, MMC leases facilities, etc. to or from, and shares technical resources and exchanges personnel including executives with, Nissan. -

Bank of Japan's Exchange-Traded Fund Purchases As An

ADBI Working Paper Series BANK OF JAPAN’S EXCHANGE-TRADED FUND PURCHASES AS AN UNPRECEDENTED MONETARY EASING POLICY Sayuri Shirai No. 865 August 2018 Asian Development Bank Institute Sayuri Shirai is a professor of Keio University and a visiting scholar at the Asian Development Bank Institute. The views expressed in this paper are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of ADBI, ADB, its Board of Directors, or the governments they represent. ADBI does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this paper and accepts no responsibility for any consequences of their use. Terminology used may not necessarily be consistent with ADB official terms. Working papers are subject to formal revision and correction before they are finalized and considered published. The Working Paper series is a continuation of the formerly named Discussion Paper series; the numbering of the papers continued without interruption or change. ADBI’s working papers reflect initial ideas on a topic and are posted online for discussion. Some working papers may develop into other forms of publication. Suggested citation: Shirai, S.2018.Bank of Japan’s Exchange-Traded Fund Purchases as an Unprecedented Monetary Easing Policy.ADBI Working Paper 865. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute. Available: https://www.adb.org/publications/boj-exchange-traded-fund-purchases- unprecedented-monetary-easing-policy Please contact the authors for information about this paper. Email: [email protected] Asian Development Bank Institute Kasumigaseki Building, 8th Floor 3-2-5 Kasumigaseki, Chiyoda-ku Tokyo 100-6008, Japan Tel: +81-3-3593-5500 Fax: +81-3-3593-5571 URL: www.adbi.org E-mail: [email protected] © 2018 Asian Development Bank Institute ADBI Working Paper 865 S. -

Abenomics' Effect on Gender Inequality in Japanese Society And

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Honors College Theses 2021 Abenomics’ Effect on Gender Inequality in Japanese Society and the Workplace Arianna C. Johnson Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses Part of the Japanese Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Arianna C., "Abenomics’ Effect on Gender Inequality in Japanese Society and the Workplace" (2021). Honors College Theses. 583. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses/583 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abenomics’ Effect on Gender Inequality in Japanese Society and the Workplace An Honors Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in Political Science and International Studies. By Arianna C. Johnson Under the mentorship of Dr. Christopher M. Brown ABSTRACT In this study, I determine the extent to which Japan’s shrinking workforce population has been affected by gender roles. Many Asian countries are experiencing a prominent decline in birth rate and population, which has increased global interest in these issues. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and Japanese government officials have eagerly responded, pushing Japanese women into the labor force as a possible solution. However, this decision has unanticipated drawbacks, which requires officials to address Japanese women’s concerns in and outside of the workplace. I argue that the Japanese government will have more success by addressing these needs, creating a more gender-equal society for Japanese women. -

Into the Future on Three Wheels

Mitsubishi The 9th Grand Prix Winner A Bimonthly Review of the Mitsubishi Companies and Their People Around the World 2009-2010 Asian Children's2008- Enikki Festa 2009 Winners December & January Grand Prix Japan Humans are social beings. People live in groups. We Bangladeshis like to live with our parents, our brothers and sisters, our grandparents, and other relatives. In our family, I live with my brother, my parents, and my grandmother. We share each other’s joys and sorrows. That makes our lives fulfilling. Cycling * The above sentences contained in this Enikki has been translated from Bengali to English. Into the Future The 9th Grand Prix Winner on Three Wheels Sadia Islam Mowtushy Age:11 Girl People’s Republic of Bangladesh “Wrapping Up the Year with Toshikoshi Soba” oba is a Japanese noodle that is eaten in various ways longevity, because it is long and thin. There are many other depending on the season. In summer, soba is served cold explanations and no single theory can claim to be the definitive S and dipped in a chilled sauce; in winter, it comes in a hot truth, but this only adds to the mystique of toshikoshi soba. broth. Soba is often garnished with tasty tidbits, such as tempura shrimp, or with a bit of boiled spinach to add a touch of color. Soba has been a favorite of Japanese people for centuries and the popular buckwheat noodle has even secured a role in various Japanese traditions, including the New Year’s celebration. Japanese people commonly eat soba on New Year’s Eve, when the old year intersects with the new year, and this is known as toshikoshi or “year-crossing” soba. -

The Causes of the Japanese Lost Decade: an Extension of Graduate Thesis

The Causes of the Japanese Lost Decade: An Extension of Graduate Thesis 経済学研究科経済学専攻博士後期課程在学 荒 木 悠 Haruka Araki Table of Contents: Ⅰ.Introduction Ⅱ.The Bubble and Burst: the Rising Sun sets into the Lost Decade A.General Overview Ⅲ.Major Causes of the Bubble Burst A.Financial Deregulation B.Asset Price Deflation C.Non-Performing Loans D.Investment Ⅳ.Theoretical Background and Insight into the Japanese Experience Ⅴ.Conclusion Ⅰ.Introduction The “Lost Decade” – the country known as of the rising sun was not brimming with rays of hope during the 1990’s. Japan’s economy plummeted into stagnation after the bubble burst in 1991, entering into periods of near zero economic growth; an alarming change from its average 4.0 percent growth in the 1980’s. The amount of literature on the causes of the Japanese economic bubble burst is vast and its content ample, ranging from asset-price deflation, financial deregulation, deficient banking system, failing macroeconomic policies, etc. This paper, an overview of this writer’s graduate thesis, re-examines the post-bubble economy of Japan, an endeavor supported by additional past works coupled with original data analysis, beginning with a general overview of the Japanese economy during the bubble compared to after the burst. Several theories carried by some scholars were chosen as this paper attempts to relate the theory to the actuality of the Japanese experience during the lost decade. - 31 - Ⅱ.The Bubble and Burst: the Rising Sun to the Lost Decade A. General Overview The so-called Japanese “bubble economy” marked high economic growth. The 1973 period of high growth illustrated an average real growth rate of GDP/capita of close to 10 percent. -

Monthly Trading Value of Most Active Stocks (Sep.2011) 1St Section

Monthly Trading Value of Most Active Stocks (Sep.2011) 1st Section Rank Code Issue Trading Value \ mil. 1 3632 Gree,Inc. 621,681 2 9984 SOFTBANK CORP. 525,472 3 7203 TOYOTA MOTOR CORPORATION 508,576 4 6954 FANUC CORPORATION 474,028 5 9501 The Tokyo Electric Power Company,Incorporated 383,303 6 8316 Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group,Inc. 371,373 7 9433 KDDI CORPORATION 367,528 8 7751 CANON INC. 344,371 9 6301 KOMATSU LTD. 342,788 10 8306 Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group,Inc. 335,566 11 7267 HONDA MOTOR CO.,LTD. 325,041 12 7201 NISSAN MOTOR CO.,LTD. 300,329 13 8411 Mizuho Financial Group,Inc. 292,432 14 2432 DeNA Co.,Ltd. 280,373 15 8058 Mitsubishi Corporation 273,889 16 2914 JAPAN TOBACCO INC. 268,618 17 8031 MITSUI & CO.,LTD. 257,682 18 6502 TOSHIBA CORPORATION 257,679 19 6758 SONY CORPORATION 247,379 20 6501 Hitachi,Ltd. 245,548 21 9983 FAST RETAILING CO.,LTD. 242,756 22 4502 Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited 232,589 23 9437 NTT DOCOMO,INC. 229,511 24 9432 NIPPON TELEGRAPH AND TELEPHONE CORPORATION 199,544 25 8591 ORIX CORPORATION 197,121 26 8604 Nomura Holdings, Inc. 182,408 27 3382 Seven & I Holdings Co.,Ltd. 182,138 28 8035 Tokyo Electron Limited 161,453 29 7202 ISUZU MOTORS LIMITED 161,231 30 7011 Mitsubishi Heavy Industries,Ltd. 159,430 31 6971 KYOCERA CORPORATION 153,831 32 5233 TAIHEIYO CEMENT CORPORATION 152,939 33 6665 Elpida Memory,Inc. 151,463 34 6762 TDK Corporation 150,719 35 8001 ITOCHU Corporation 149,228 36 6752 Panasonic Corporation 148,099 37 4063 Shin-Etsu Chemical Co.,Ltd.