Bank of Japan's Exchange-Traded Fund Purchases As An

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Internationalization of the Japanese Yen

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Macroeconomic Linkage: Savings, Exchange Rates, and Capital Flows, NBER-EASE Volume 3 Volume Author/Editor: Takatoshi Ito and Anne Krueger, editors Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-38669-4 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/ito_94-1 Conference Date: June 17-19, 1992 Publication Date: January 1994 Chapter Title: On the Internationalization of the Japanese Yen Chapter Author: Hiroo Taguchi Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c8538 Chapter pages in book: (p. 335 - 357) 13 On the Internationalization of the Japanese Yen Hiroo Taguchi The internationalization of the yen is a widely discussed topic, among not only economists but also journalists and even politicians. Although various ideas are discussed under this heading, three are the focus of attention: First, and the most narrow, is the use of yen by nonresidents. Second is the possibility of Asian economies forming an economic bloc with Japan and the yen at the center. Third, is the possibility that the yen could serve as a nominal anchor for Asian countries, resembling the role played by the deutsche mark in the Euro- pean Monetary System (EMS). Sections 13.1-13.3 of this paper try to give a broad overview of the key facts concerning the three topics, above. The remaining sections discuss the international role the yen could play, particularly in Asia. 13.1 The Yen as an Invoicing Currency Following the transition to a floating exchange rate regime, the percentage of Japan’s exports denominated in yen rose sharply in the early 1970s and con- tinued to rise to reach nearly 40 percent in the mid- 1980s, a level since main- tained (table 13.1). -

Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund

Fact sheet | June 30, 2021 Vanguard® Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund Domestic stock fund | Institutional Plus Shares Fund facts Risk level Total net Expense ratio Ticker Turnover Inception Fund Low High assets as of 04/29/21 symbol rate date number 1 2 3 4 5 $269,281 MM 0.02% VSMPX 8.0% 04/28/15 1871 Investment objective Benchmark Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund seeks CRSP US Total Market Index to track the performance of a benchmark index that measures the investment return of the Growth of a $10,000 investment : April 30, 2015—D ecember 31, 2020 overall stock market. $20,143 Investment strategy Fund as of 12/31/20 The fund employs an indexing investment $20,131 approach designed to track the performance of Benchmark the CRSP US Total Market Index, which as of 12/31/20 represents approximately 100% of the 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015* 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 investable U.S. stock market and includes large-, mid-, small-, and micro-cap stocks regularly traded on the New York Stock Exchange and Annual returns Nasdaq. The fund invests by sampling the index, meaning that it holds a broadly diversified collection of securities that, in the aggregate, approximates the full Index in terms of key characteristics. These key characteristics include industry weightings and market capitalization, as well as certain financial measures, such as Annual returns 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015* 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 price/earnings ratio and dividend yield. Fund — — — — -3.28 12.69 21.19 -5.15 30.82 21.02 For the most up-to-date fund data, Benchmark — — — — -3.29 12.68 21.19 -5.17 30.84 20.99 please scan the QR code below. -

Current Fact Sheet

Quarter 2, 2021 Mondrian U.S. Small Cap Equity Fund MPUSX Fund Objective Fund Performance The Fund seeks long-term total return. Since Quarter YTD 1 Year Inception * Fund Strategy Mondrian U.S. Small Cap Equity Fund 0.65%14.50% 44.76% 10.85% The Fund invests primarily in equity securities of U.S. Russell 2000 4.29%17.54% 62.03% 23.05% small-capitalization companies. Mondrian applies a Russell 2000 Value 4.56%26.69% 73.28% 18.77% defensive, value-oriented process that seeks to * Fund Inception December 17, 2018. Periods over one year are annualized identify undervalued securities that we believe will The performance data quoted represents past performance. Past performance is provide strong excess returns over a full market no guarantee of future results. The investment return and principal value of an cycle. investment will fluctuate so that an investor's shares, when redeemed, may be worth more or less than their original cost and current performance may be lower or higher than performance quoted. For performance data current to the most Fundamental research is strongly emphasized. recent month end, please call 888-832-4386. Extensive contact with companies enhances Sector Allocation qualitative and quantitative desk research, both prior to the purchase of a stock and after its 37.9% Industrials inclusion in the portfolio. 14.3% Information 23.6% The Fund is subject to market risks. Mondrian’s Technology 13.6% 11.8% approach focuses on providing a rate of return Materials meaningfully greater than the client’s domestic rate 3.8% 11.1% of inflation. -

Institutions, Competition, and Capital Market Integration in Japan

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES INSTITUTIONS, COMPETITION, AND CAPITAL MARKET INTEGRATION IN JAPAN Kris J. Mitchener Mari Ohnuki Working Paper 14090 http://www.nber.org/papers/w14090 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 June 2008 A version of this paper is forthcoming in the Journal of Economic History. We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Ronald Choi, Jennifer Combs, Noriko Furuya, Keiko Suzuki, and Genna Tan for help in assembling the data. Mitchener would also like to thank the Institute for Monetary and Economic Studies at the Bank of Japan for its hospitality and generous research support while serving as a visiting scholar at the Institute in 2006, and the Dean Witter Foundation for additional financial support. We also thank conference participants at the BETA Workshop in Strasbourg, France and seminar participants at the Bank of Japan for comments and suggestions. The views presented in this paper are solely those of the authors, and do not necessarily represent those of the Bank of Japan, its staff, or the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2008 by Kris J. Mitchener and Mari Ohnuki. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Institutions, Competition, and Capital Market Integration in Japan Kris J. Mitchener and Mari Ohnuki NBER Working Paper No. -

The Causes of the Japanese Lost Decade: an Extension of Graduate Thesis

The Causes of the Japanese Lost Decade: An Extension of Graduate Thesis 経済学研究科経済学専攻博士後期課程在学 荒 木 悠 Haruka Araki Table of Contents: Ⅰ.Introduction Ⅱ.The Bubble and Burst: the Rising Sun sets into the Lost Decade A.General Overview Ⅲ.Major Causes of the Bubble Burst A.Financial Deregulation B.Asset Price Deflation C.Non-Performing Loans D.Investment Ⅳ.Theoretical Background and Insight into the Japanese Experience Ⅴ.Conclusion Ⅰ.Introduction The “Lost Decade” – the country known as of the rising sun was not brimming with rays of hope during the 1990’s. Japan’s economy plummeted into stagnation after the bubble burst in 1991, entering into periods of near zero economic growth; an alarming change from its average 4.0 percent growth in the 1980’s. The amount of literature on the causes of the Japanese economic bubble burst is vast and its content ample, ranging from asset-price deflation, financial deregulation, deficient banking system, failing macroeconomic policies, etc. This paper, an overview of this writer’s graduate thesis, re-examines the post-bubble economy of Japan, an endeavor supported by additional past works coupled with original data analysis, beginning with a general overview of the Japanese economy during the bubble compared to after the burst. Several theories carried by some scholars were chosen as this paper attempts to relate the theory to the actuality of the Japanese experience during the lost decade. - 31 - Ⅱ.The Bubble and Burst: the Rising Sun to the Lost Decade A. General Overview The so-called Japanese “bubble economy” marked high economic growth. The 1973 period of high growth illustrated an average real growth rate of GDP/capita of close to 10 percent. -

Monthly Economic Update

In this month’s recap: Stocks moved higher as investors looked past accelerating inflation and the Fed’s pivot on monetary policy. Monthly Economic Update Presented by Ray Lazcano, July 2021 U.S. Markets Stocks moved higher last month as investors looked past accelerating inflation and the Fed’s pivot on monetary policy. The Dow Jones Industrial Average slipped 0.07 percent, but the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index rose 2.22 percent. The Nasdaq Composite led, gaining 5.49 percent.1 Inflation Report The May Consumer Price Index came in above expectations. Prices increased by 5 percent for the year-over-year period—the fastest rate in nearly 13 years. Despite the surprise, markets rallied on the news, sending the S&P 500 to a new record close and the technology-heavy Nasdaq Composite higher.2 Fed Pivot The Fed indicated that two interest rate hikes in 2023 were likely, despite signals as recently as March 2021 that rates would remain unchanged until 2024. The Fed also raised its inflation expectations to 3.4 percent, up from its March projection of 2.4 percent. This news unsettled 3 the markets, but the shock was short-lived. News-Driven Rally In the final full week of trading, stocks rallied on the news of an agreement regarding the $1 trillion infrastructure bill and reports that banks had passed the latest Federal Reserve stress tests. Sector Scorecard 07072021-WR-3766 Industry sector performance was mixed. Gains were realized in Communication Services (+2.96 percent), Consumer Discretionary (+3.22 percent), Energy (+1.92 percent), Health Care (+1.97 percent), Real Estate (+3.28 percent), and Technology (+6.81 percent). -

International Trading Companies: Building on the Japanese Model Robert W

Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business Volume 4 Issue 2 Fall Fall 1982 International Trading Companies: Building on the Japanese Model Robert W. Dziubla Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njilb Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Robert W. Dziubla, International Trading Companies: Building on the Japanese Model, 4 Nw. J. Int'l L. & Bus. 422 (1982) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business by an authorized administrator of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business International Trading Companies: Building On The Japanese Model Robert W. Dziubla* Passageof the Export Trading Company Act of 1982provides new op- portunitiesfor American business to organize and operate general trading companies. Afterpresenting a thorough history and description of the Japa- nese sogoshosha, Mr. Dziubla gives several compelling reasonsfor Ameri- cans to establish export trading companies. He also examines the changes in United States banking and antitrust laws that have resultedfrom passage of the act, and offers suggestionsfor draftingguidelines, rules, and regula- tionsfor the Export Trading Company Act. For several years, American legislators and businessmen have warned that if America is to balance its international trade-and in particular offset the cost of importing billions of dollars worth of oil- she must take concrete steps to increase her exporting capabilities., On October 8, 1982, the United States took just such a step when President Reagan signed into law the Export Trading Company Act of 1982,2 which provides for the development of international general trading companies similar to the ones used so successfully by the Japanese. -

Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund

Fact sheet | June 30, 2021 Vanguard® Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund Domestic stock fund | Institutional Shares Fund facts Risk level Total net Expense ratio Ticker Turnover Inception Fund Low High assets as of 04/29/21 symbol rate date number 1 2 3 4 5 $227,984 MM 0.03% VITSX 8.0% 07/07/97 0855 Investment objective Benchmark Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund seeks Spliced Total Stock Market Index to track the performance of a benchmark index that measures the investment return of the Growth of a $10,000 investment : January 31, 2011—D ecember 31, 2020 overall stock market. $35,603 Investment strategy Fund as of 12/31/20 The fund employs an indexing investment $35,628 approach designed to track the performance of Benchmark the CRSP US Total Market Index, which as of 12/31/20 represents approximately 100% of the 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 investable U.S. stock market and includes large-, mid-, small-, and micro-cap stocks regularly traded on the New York Stock Exchange and Annual returns Nasdaq. The fund invests by sampling the index, meaning that it holds a broadly diversified collection of securities that, in the aggregate, approximates the full Index in terms of key characteristics. These key characteristics include industry weightings and market capitalization, as well as certain financial measures, such as Annual returns 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 price/earnings ratio and dividend yield. Fund 1.09 16.42 33.49 12.56 0.42 12.67 21.17 -5.16 30.81 21.00 For the most up-to-date fund data, Benchmark 1.08 16.44 33.51 12.58 0.40 12.68 21.19 -5.17 30.84 20.99 please scan the QR code below. -

Title the Japanese Currency Policy and the British Banks in Asia In

The Japanese Currency Policy and the British Banks in Asia in Title 1870s-1890s Author(s) MOTOYAMA, Yoshihico; YOKOYAMA, Shisei Citation The Kyoto University Economic Review (1995), 64(1): 1-8 Issue Date 1995-02 URL https://doi.org/10.11179/ker1926.64.1 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University THE KYOTO UNIVERSITY ECONOMIC REVIEW MEMOIRS OFTHE FACULTY OF ECONOMICS KYOTO UNIVERSITY VOLUME LXIV NUMBER 1 (APRIL 1994) WHOLE NUMBER 136 The Japanese Currency Policy and the British Banks in Asia in 1870s - 1890s 牢 ( Yoshihiko MOTOYAMA'" and Shisei YOKOYAMA I The Silver Dollar and the Japanese Silver Yen in Asia before 1897 In Asia before l870s , Spanish silver dollars (including Mexican dollars) were the most familiar and influential import from the West. They were widely circulated in Asia from the sixteenth to the middle of the nineteenth century. But they were generally less favoured by most Asian Government , though they were made legal tender in Singapore in 1867. During the 1870s, the value of silver beュ gan to depreciate. This meant the opening the “ T rade Dollar Era". Western countries began to mint and export silver trade dollars for circulation in silver-using countries. The Hong Kong dollar was minted in 1866, the US trade dollar in 1873, and the British dollar in 1895. They did so beュ cause the value of silver in silver-using countries , particularly in China , were not depreciating at the same rate as it was in the Western Countries. So they wanted their own trade dollar to replace Mexュ ican dollars in Asia. -

Investing in the Marketplace

Investing in the Marketplace Prudential Retirement When you hear people talk about “the market,” you might think Did you know... we agree on what that means. Truth is, there are many indexes that represent differing segments of the market. And these …there is even indexes don’t always move in tandem. Understanding some of an index that the key ones can help you diversify your investments to better represent the economy as a whole. purports to track The Dow Jones Industrial Average (The Dow) is one of the oldest, most investor anxiety? well-know indexes and is often used to represent the economy as a Dubbed “The Fear whole. Truth is, though, The Dow only includes 30 stocks of the world’s largest, most influential companies. Why is it called an “average?” Index,” the proper Originally, it was computed by adding up the per-share price of its stocks, and dividing by the number of companies. name of the Chicago The Standard & Poor’s 500 Index (made up of 500 of the most widely- Board Options traded U.S. stocks) is larger and more diverse than The Dow. Because it represents about 70% of the total value of the U.S. stock market, the Exchange’s index is S&P 500 is a better indication of how the U.S. marketplace is moving as a whole. the VIX Index, Sometimes referred to as the “total stock market index,” the Wilshire and measures the 5000 Index includes about 7,000 of the more than 10,000 publicly traded companies with headquarters in the U.S. -

Kirin Report 2016

KIRIN REPORT 2016 REPORT KIRIN Kirin Holdings Company, Limited Kirin Holdings Company, KIRIN REPORT 2016 READY FOR A LEAP Toward Sustainable Growth through KIRIN’s CSV Kirin Holdings Company, Limited CONTENTS COVER STORY OUR VISION & STRENGTH 2 What is Kirin? OUR LEADERSHIP 4 This section introduces the Kirin Group’s OUR NEW DEVELOPMENTS 6 strengths, the fruits of the Group’s value creation efforts, and the essence of the Group’s results OUR ACHIEVEMENTS and CHALLENGES to OVERCOME 8 and issues in an easy-to-understand manner. Our Value Creation Process 10 Financial and Non-Financial Highlights 12 P. 2 SECTION 1 To Our Stakeholders 14 Kirin’s Philosophy and TOPICS: Initiatives for Creating Value in the Future 24 Long-Term Management Vision and Strategies Medium-Term Business Plan 26 This section explains the Kirin Group’s operating environment and the Group’s visions and strate- CSV Commitment 28 gies for sustained growth in that environment. CFO’s Message 32 Overview of the Kirin Group’s Business 34 P. 14 SECTION 2 Advantages of the Foundation as Demonstrated by Examples of Value Creation Kirin’s Foundation Revitalizing the Beer Market 47 Todofuken no Ichiban Shibori 36 for Value Creation A Better Green Tea This section explains Kirin’s three foundations, Renewing Nama-cha to Restore Its Popularity 38 which represent Group assets, and provides Next Step to Capture Overseas Market Growth examples of those foundations. Myanmar Brewery Limited 40 Marketing 42 Research & Development 44 P. 36 Supply Chain 46 SECTION 3 Participation in the United Nations Global Compact 48 Kirin’s ESG ESG Initiatives 49 This section introduces ESG activities, Human Resources including the corporate governance that —Valuable Resource Supporting Sustained Growth 50 supports value creation. -

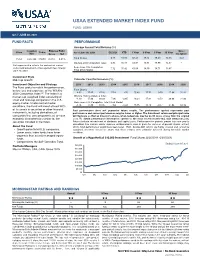

USAA Extended Market Index Fund Fact Sheet

USAA EXTENDED MARKET INDEX FUND FUND: USMIX Q2 // JUNE 30, 2021 FUND FACTS PERFORMANCE Average Annual Total Returns (%) Inception Expense Ratio: Since Class Ticker As of June 30, 2021 Q2 2021 YTD 1 Year 3 Year 5 Year 10 Year Date Gross Net Inception Fund Shares 6.71 15.83 62.43 18.33 18.49 13.55 9.33 Fund 10/27/00 USMIX 0.42% 0.42% Wilshire 4500 Completion Index 6.83 16.11 63.07 18.81 18.99 14.32 – Net expense ratio reflects the contractual waiver Dow Jones U.S. Completion and/or reimbursement of management fees through 7.12 15.42 61.60 18.50 18.71 13.87 – June 30, 2023. Total Stock Market Investment Style Mid-Cap Growth Calendar Year Performance (%) Investment Objective and Strategy 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 The Fund seeks to match the performance, before fees and expenses, of the Wilshire Fund Shares -4.03 17.47 37.26 7.18 -3.76 15.48 17.72 -9.70 27.94 31.20 4500 Completion IndexSM. The Index is a market cap-weighted index consisting of Wilshire 4500 Completion Index -4.10 17.99 38.39 7.96 -2.65 17.84 -9.53 28.06 31.99 small and mid-cap companies in the U.S. 18.54 equity market. Under normal market Dow Jones U.S. Completion Total Stock Market conditions, the Fund will invest at least 80% -3.76 17.89 38.05 7.63 -3.42 15.75 18.12 -9.57 27.94 32.16 of its assets in securities or other financial Past performance does not guarantee future results.