Exporting America: the U.S. Information Centers and German Reconstruction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Foreign Service Journal, February 1945

tr * TVA •' g/IC AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE VOL. 22, NO. 2 JOURNAL FEBRUARY, 1945 - .■% * ■ * Jfv- - ' v» .1? . .V ,rf- * ' JiL ■**•*.. v ■ > ' 1. Hk^. _ •k. e X/ %s ; * , ** 1' < ' ' * ■ > fij I g v . ■. ' THIS IS NOT FRANCE, BUT IT HAS TAKEN a world war to make that American vintners have a tradition many of us here at home realize that which reaches back into Colonial days. in some ways we are not as dependent To their surprise, when other sources upon foreign sources as we had thought. were cut off, they found that American We have frequently found that our own wines are often superior to the imported home-grown products are as good as — peacetime products. We know this be¬ and often better than —those we once cause unbiased experts say so —and be¬ imported as a matter of course. cause the active demand for CrestaBlanca One such instance is California wine. is increasing daily. People in the States used to believe that Maybe you haven’t yet had the op¬ only European wines could measure up portunity to enjoy Cresta Blanca. If not, to every standard of excellence. Perhaps you owe it to your critical taste to try they were not aware that the climate and some of its nine superb types...and to soil of California is comparable to that let your friends share the experience of of the most famous French vineyards; so many of us back home. CRESTA BLANCA for over fifty years the finest of North American wines CONTENTS FEBRUARY. 1945 Cover: Chile’s Winter Fantasy Photo by Robert W. -

Barthé, Darryl G. Jr.Pdf

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Becoming American in Creole New Orleans: Family, Community, Labor and Schooling, 1896-1949 Darryl G. Barthé, Jr. Doctorate of Philosophy in History University of Sussex Submitted May 2015 University of Sussex Darryl G. Barthé, Jr. (Doctorate of Philosophy in History) Becoming American in Creole New Orleans: Family, Community, Labor and Schooling, 1896-1949 Summary: The Louisiana Creole community in New Orleans went through profound changes in the first half of the 20th-century. This work examines Creole ethnic identity, focusing particularly on the transition from Creole to American. In "becoming American," Creoles adapted to a binary, racialized caste system prevalent in the Jim Crow American South (and transformed from a primarily Francophone/Creolophone community (where a tripartite although permissive caste system long existed) to a primarily Anglophone community (marked by stricter black-white binaries). These adaptations and transformations were facilitated through Creole participation in fraternal societies, the organized labor movement and public and parochial schools that provided English-only instruction. -

Coca-Cola Enterprises, Inc

A Progressive Digital Media business COMPANY PROFILE Coca-Cola Enterprises, Inc. REFERENCE CODE: 0117F870-5021-4FB1-837B-245E6CC5A3A9 PUBLICATION DATE: 11 Dec 2015 www.marketline.com COPYRIGHT MARKETLINE. THIS CONTENT IS A LICENSED PRODUCT AND IS NOT TO BE PHOTOCOPIED OR DISTRIBUTED Coca-Cola Enterprises, Inc. TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Company Overview ........................................................................................................3 Key Facts.........................................................................................................................3 Business Description .....................................................................................................4 History .............................................................................................................................5 Key Employees ...............................................................................................................8 Key Employee Biographies .........................................................................................10 Major Products & Services ..........................................................................................18 Revenue Analysis .........................................................................................................20 SWOT Analysis .............................................................................................................21 Top Competitors ...........................................................................................................25 -

Signature Cocktails Glass $15 Pitcher

SIGNATURE COCKTAILS GLASS $15 PITCHER $60 THE OASIS bacardí raspberry, bacardí limón, muddled lemons & blueberries, lemonade, red bull STRAWBERRY CRUSH tito’s, muddled strawberries, lemon, basil leaves PURPLE RAIN ketel one, pineapple, blackberries, raspberries, lemonade WATERMELON MARGARITA herradura blanco, watermelon, cointreau, agave nectar, sour mix EL DIABLO cazadores reposado, cointreau, muddled cilantro & jalapeño, passion fruit, orange juice CUCUMBER COOLER hendricks, st. germain, muddled cucumbers, lime, club soda JACK OF HEARTS jack daniel’s, chambord, blackberries, lemonade BEACH CLUB PIÑA COLADA $26 PINEAPPLE DELIGHT $26 oak & palm coconut rum, coconut flor de caña, banana & mango, cream, pineapple chunks, served in a pineapple served in a coconut topped with myers’s rum and toasted coconut shavings All orders will receive an automatic 18% gratuity. MOJITOS $15 MANGO FUSION bacardí mango fusion, mango, muddled mint leaves & lime COCONUT bacardí coconut, coconut cream, muddled mint leaves, lime & sugar cane DOMESTIC BEER $8 IMPORTED BEER $14 16 oz. aluminum bottles 24 oz. aluminum cans BUD LIGHT CORONA BUDWEISER HEINEKEN COORS LIGHT MICHELOB ULTRA MILLER LITE BEER BUCKETS (5) DOMESTIC $32 (4) IMPORTED $42 HARD SELTZER - WHITE CLAW 12 oz. can BLACK CHERRY OR LIME FLAVOR SINGLE $7 BUCKET (5)$28 HIGH NOON 12 oz.can PINEAPPLE OR WATERMELON FLAVOR SINGLE $7 BUCKET (5) $28 SPECIALTY FROZEN $15 IN BLOOM FROSE LEMON BLUEBERRY ketel one botanical, rose wine, hibiscus syrup ketel one citron, blueberries, lemon ice SANGRIA GLASS $12 PITCHER -

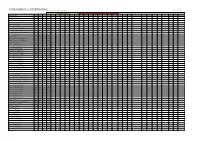

Symbols & Indies Planogram 1/1.25M England & Wales

SYMBOLS & INDIES PLANOGRAM 1/1.25M ENGLAND & WALES DRINK NOW SYMBOLS & INDIES PLANOGRAM 1/1.25M ENGLAND & WALES DRINK NOW SYMBOLS & INDIES PLANOGRAM 1/1.25M ENGLAND & WALES DRINK NOW SHELF SHELF 11 SHELF SHELF 22 SHELF SHELF 33 SHELF SHELF 44 SHELF SHELF 55 Shelf 1 Shelf 2 Shelf 3 Shelf 4 Shelf 5 FantaShelf 1Orange Pm 65p 330ml DrShelf Pepper 2 Drink Pm 1.09 / 2 For 2.00 500ml FantaShelf 3Orange Pm 1.09 / 2 For 2.00 500ml FantaShelf 4Lemon 500ml SpriteShelf 5Std 500ml IrnFanta Bru OrangeDrink Pm Pm 59p 65p 330ml 330ml MountainDr Pepper Dew Drink Drink Pm Pm1.09 1.19 / 2 For500ml 2.00 500ml FantaFanta FruitOrange Twist Pm Pm 1.09 1.09/2 / 2 For For 2.00 2.00 500ml 500ml FantaFanta ZeroLemon Grape 500ml 500ml IrnSprite Bru StdDrink 500ml Pm 99p 500ml DrIrn PepperBru Drink Std Pm Pm 59p 65p 330ml 330ml CocaMountain Cola Dew Std PmDrink 1.25 Pm 500ml 1.19 500ml DietFanta Coke Fruit Std Twist Pm Pm 1.09 1.09/2 / 2 For For 2.00 2.00 500ml 500ml PepsiFanta MaxZero Std Grape Nas 500mlPm 1.00 / 2 For 1.70 500ml PepsiIrn Bru Max Drink Cherry Pm 99p Nas 500ml Pm 1.00 / 2 F 1.70 500ml CocaDr Pepper Cola StdStd CanPm 65pPm 79p330ml 330ml CocaCoca ColaCola CherryStd Pm Pm 1.25 1.25 500ml 500ml CocaDiet Coke Cola StdZero Pm Std 1.09 Nas / Pm2 For 1.09 2.00 / 2 500ml For 2.00 500ml PepsiPepsi StdMax Pm Std 1.19 Nas 500ml Pm 1.00 / 2 For 1.70 500ml DietPepsi Pepsi Max Std Cherry Pm 1.00Nas Pm/ 2 For1.00 1.70 / 2 F 500ml 1.70 500ml DietCoca Coke Cola Std Std Can Can Pm Pm 69p 79p 330ml 330ml MonsterCoca Cola Energy Cherry Original Pm 1.25 Pm 500ml 1.35 -

Allergen Information | All Soft Drinks & Minerals

ALLERGEN INFORMATION | ALL SOFT DRINKS & MINERALS **THIS INFORMATION HAS BEEN RECORDED AND LISTED ON SUPPLIER ADVICE** DAYLA WILL ACCEPT NO RESPONSIBILITY FOR INACCURATE INFORMATION RECEIVED Cereals containing GLUTEN Nuts Product Description Type Pack ABV % Size Wheat Rye Barley Oats Spelt Kamut Almonds Hazelnut Walnut Cashews Pecan Brazil Pistaccio Macadamia Egg Crustacean Lupin Sulphites >10ppm Celery Peanuts Milk Fish Soya Beans Mollusc Mustard Sesame Seeds Appletiser 24x275ml Case Minerals Case 0 275ml BG Cox's Apple Sprkl 12x275ml Minerals Case 0 275ml BG Cranberry&Orange Sprkl 12x275ml Minerals Case 0 275ml BG E'flower CorDial 6x500ml Minerals Case 0 500ml BG E'flower Sprkl 12x275ml Minerals Case 0 275ml BG Ginger&Lemongrass Sprkl 12x275ml Minerals Case 0 275ml BG Ginger&Lemongrass Sprkl SW 12X275ml Minerals Case 0 275ml BG Pomegranate&E'flower Sprkl 12X275ml Minerals Case 0 275ml BG Strawberry CorDial 6x500ml Minerals Case 0 500ml Big Tom Rich & Spicy Minerals Case 0 250ml √ Bottlegreen Cox's Apple Presse 275ml NRB Minerals Case 0 275ml Bottlegreen ElDerflower Presse 275ml NRB Minerals Case 0 275ml Britvic 100 Apple 24x250ml Case Minerals Case 0 250ml Britvic 100 Orange 24x250ml Case Minerals Case 0 250ml Britvic 55 Apple 24x275ml Case Minerals Case 0 275ml Britvic 55 Orange 24x275ml Case Minerals Case 0 275ml Britvic Bitter Lemon 24x125ml Case Minerals Case 0 125ml Britvic Blackcurrant CorDial 12x1l Case Minerals Case 0 1l Britvic Cranberry Juice 24x160ml Case Minerals Case 0 160ml Britvic Ginger Ale 24x125ml Case Minerals Case -

Military Government Officials, US Policy, and the Occupation of Bavaria, 1945-1949

Coping with Crisis: Military Government Officials, U.S. Policy, and the Occupation of Bavaria, 1945-1949 By Copyright 2017 John D. Hess M.A., University of Kansas, 2013 B.S., Oklahoma State University, 2011 Submitted to the graduate degree program in the Department of History and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Chair: Adrian R. Lewis Theodore A. Wilson Sheyda Jahanbani Erik R. Scott Mariya Omelicheva Date Defended: 28 April 2017 The dissertation committee for John D. Hess certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Coping with Crisis: Military Government Officials, U.S. Policy, and the Occupation of Bavaria, 1945-1949 Chair: Adrian R. Lewis Date Approved: 28 April 2017 ii Abstract This dissertation explores the implementation of American policy in postwar Germany from the perspective of military government officers and other occupation officials in the Land of Bavaria. It addresses three main questions: How did American military government officials, as part of the institution of the Office of Military Government, Bavaria (OMGB), respond to the challenges of the occupation? How did these individuals interact with American policy towards defeated Germany? And, finally, how did the challenges of postwar Germany shape that relationship with American policy? To answer these questions, this project focuses on the actions of military government officers and officials within OMGB from 1945 through 1949. Operating from this perspective, this dissertation argues that American officials in Bavaria possessed a complicated, often contradictory, relationship with official policy towards postwar Germany. -

The Portrayal of Germany, Germans and German-Americans by Three Eastern Iowa Newspapers During World War I Lucinda Lee Stephenson Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1985 Scapegoats, slackers and spies: the portrayal of Germany, Germans and German-Americans by three eastern Iowa newspapers during World War I Lucinda Lee Stephenson Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Journalism Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Stephenson, Lucinda Lee, "Scapegoats, slackers and spies: the portrayal of Germany, Germans and German-Americans by three eastern Iowa newspapers during World War I " (1985). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 298. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/298 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Scapegoats. slackers and spies: The portrayal of Germany. Germans and German-Americans by three eastern Iowa newspapers during World War I .:Z5/-/ /9?~~ by _. ..t- .. ,/~-", ... J .... - j"' ... Lucinda Lee Stephenson A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Journalism and Mass Communication Signatures have been redacted for privacy Iowa State University Ames. Iowa Copyright (c) Lucinda L. Stephenson. 198~. All rights reserved. Ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER 1. INfRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER II. THE WAR REACHES lOW A 21 CHAPTER III. THE INVASION OF BELGIUM 29 CHAPTER IV. THE SINKING OF THE LUSITANIA 40 CHAPTER V. -

APRIL 2015 CURRICULUM VITAE MARKOVITS, Andrei Steven Department of Political Science the University of Michigan 5700 Haven H

APRIL 2015 CURRICULUM VITAE MARKOVITS, Andrei Steven Department of Political Science The University of Michigan 5700 Haven Hall 505 South State Street Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1045 Telephone: (734) 764-6313 Fax: (734) 764-3522 E-mail: [email protected] Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures The University of Michigan 3110 Modern Language Building 812 East Washington Street Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1275 Telephone: (734) 764-8018 Fax: (734) 763-6557 E-mail: [email protected] Date of Birth: October 6, 1948 Place of Birth: Timisoara, Romania Citizenship: U.S.A. Recipient of the Bundesverdienstkreuz Erster Klasse, the Cross of the Order of Merit, First Class, the highest civilian honor bestowed by the Federal Republic of Germany on a civilian, German or foreign; awarded on behalf of the President of the Federal Republic of Germany by the Consul General of the Federal Republic of Germany at the General Consulate of the Federal Republic of Germany in Chicago, Illinois; March 14, 2012. PRESENT FACULTY POSITIONS Arthur F. Thurnau Professor Karl W. Deutsch Collegiate Professor of Comparative Politics and German Studies; Professor of Political Science; Professor of Germanic Languages and Literatures; and Professor of Sociology The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor FORMER FULL-TIME FACULTY POSITIONS Professor of Politics Department of Politics University of California, Santa Cruz July 1, 1992 - June 30, 1999 Chair of the Department of Politics University of California, Santa Cruz July 1, 1992 - June 30, 1995 Associate Professor of Political Science Department of Political Science Boston University July 1, 1983- June 30, 1992 Assistant Professor of Political Science Department of Government Wesleyan University July 1, 1977- June 30, 1983 Research Associate Center for European Studies Harvard University July 1, 1975 - June 30, 1999 EDUCATION Honorary Doctorate Dr. -

(8 Wings Bone In) Fried Pickles M

Welcome to Oasis Outback BBQ & Grill. Established in 2005, we have been committed in pro- viding our customers the highest quality of food and service. Awarded “the Best Customer Ser- vice in town”, our goal is to surpass and enhance your dining experience. We appreciate any compliments or concerns you may have. Thank you for choosing Oasis Outback Bar-B-Q & Chips and Salsa $3.99 Home Style Onion Rings $6.99 Flour coated and breaded to perfection. Cactus Sticks $7.99 Hand battered green beans. Plain or Hot Bottle Caps $7.99 Spicy jalapeño wheels coated in a premium beer batter. Fried Mushrooms $7.99 Baby portabellas sliced and breaded. Your choice of ranch dressing or country gravy. Buffalo Wings (8 Wings Bone In) $8.99 Plain or Saucy Hot. Fried Pickles $8.99 Lightly breaded pickle slices. Mozzarella Sticks (8 sticks ) $8.99 Coated in our garlic butter breading. Fried Popcorn Shrimp 1/2 lb: $9.99 Fried popcorn shrimp. Plain, or Hot. 1 lb: $18.99 The Sampler $28.99 Cactus Sticks, Onion Rings, Bottle Caps & Fried Pickles. (no substitutions) Thanks for choosing Oasis Outback Texas BBQ & Grill Oasis Outback has the right to refuse service to anyone. All of our meats are prepared and smoked fresh daily- served with two sides of your choice. We also offer all of our meats by the pound Mesquite Smoked Angus Brisket Plate (regular) $12.99 We mesquite smoke only the best choice angus briskets for over ten hours, trim and serve to order. St. Louis Pork Ribs Plate Half rack: $19.99 Mesquite smoked St.Louis Ribs, seasoned with our award winning rub, BBQ sauce and love. -

Paradoxes of Providing Aid: Ngos, Medicine, and Undocumented Migration in Berlin, Germany

Paradoxes of Providing Aid: NGOs, Medicine, and Undocumented Migration in Berlin, Germany Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Castaneda, Heide Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 05/10/2021 08:55:53 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/195410 PARADOXES OF PROVIDING AID: NGOS, MEDICINE, AND UNDOCUMENTED MIGRATIONINBERLIN, GERMANY by Heide Castañeda _____________________ Copyright © Heide Castañeda 2007 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY WITH A MAJOR INANTHROPOLOGY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2007 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Heide Castañeda entitled Paradoxes of Providing Aid: NGOs, Medicine, and Undocumented Migration in Berlin, Germany and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 1/12/07 Mark Nichter _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 1/12/07 Linda B. Green _______________________________________________________________________ -

Transatlantic Migration and the Politics of Belonging, 1919-1939

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects Summer 2016 Between Third Reich and American Way: Transatlantic Migration and the Politics of Belonging, 1919-1939 Christian Wilbers College of William and Mary - Arts & Sciences, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Wilbers, Christian, "Between Third Reich and American Way: Transatlantic Migration and the Politics of Belonging, 1919-1939" (2016). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1499449834. http://doi.org/10.21220/S2JD4P This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Between Third Reich and American Way: Transatlantic Migration and the Politics of Belonging, 1919-1939 Christian Arne Wilbers Leer, Germany M.A. University of Münster, Germany, 2006 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy American Studies Program The College of William and Mary August 2016 © Copyright by Christian A. Wilbers 2016 ABSTRACT Historians consider the years between World War I and World War II to be a period of decline for German America. This dissertation complicates that argument by applying a transnational framework to the history of German immigration to the United States, particularly the period between 1919 and 1939. The author argues that contrary to previous accounts of that period, German migrants continued to be invested in the homeland through a variety of public and private relationships that changed the ways in which they thought about themselves as Germans and Americans.