Vapor Pressure of Liquids Vapor Pressure and Boiling Point

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 5 Measures of Humidity Phases of Water

Chapter 5 Atmospheric Moisture Measures of Humidity 1. Absolute humidity 2. Specific humidity 3. Actual vapor pressure 4. Saturation vapor pressure 5. Relative humidity 6. Dew point Phases of Water Water Vapor n o su ti b ra li o n m p io d a a at ep t v s o io e en s n d it n io o n c freezing Liquid Water Ice melting 1 Coexistence of Water & Vapor • Even below the boiling point, some water molecules leave the liquid (evaporation). • Similarly, some water molecules from the air enter the liquid (condense). • The behavior happens over ice too (sublimation and condensation). Saturation • If we cap the air over the water, then more and more water molecules will enter the air until saturation is reached. • At saturation there is a balance between the number of water molecules leaving the liquid and entering it. • Saturation can occur over ice too. Hydrologic Cycle 2 Air Parcel • Enclose a volume of air in an imaginary thin elastic container, which we will call an air parcel. • It contains oxygen, nitrogen, water vapor, and other molecules in the air. 1. Absolute Humidity Mass of water vapor Absolute humidity = Volume of air The absolute humidity changes with the volume of the parcel, which can change with temperature or pressure. 2. Specific Humidity Mass of water vapor Specific humidity = Total mass of air The specific humidity does not change with parcel volume. 3 Specific Humidity vs. Latitude • The highest specific humidities are observed in the tropics and the lowest values in the polar regions. -

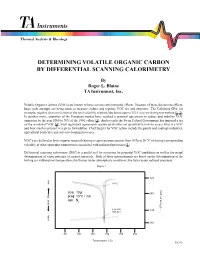

Determining Volatile Organic Carbon by Differential Scanning Calorimetry

DETERMINING VOLATILE ORGANIC CARBON BY DIFFERENTIAL SCANNING CALORIMETRY By Roger L. Blaine TA Instrument, Inc. Volatile Organic Carbons (VOCs) are known to have serious environmental effects. Because of these deleterious effects, large scale attempts are being made to measure, reduce and regulate VOC use and emission. The California EPA, for example, requires characterization of the total volatility of pesticides based upon a TGA loss-on-drying test method [1, 2]. In another move, countries of the European market have reached a protocol agreement to reduce and stabilize VOC emissions by the year 2000 to 70% of the 1991 values [3]. And recently the Swiss Federal Government has imposed a tax on the amount of VOC [4]. Such regulatory agreements require qualitative and quantitative tools to assess what is a VOC and how much is present in a given formulation. Chief targets for VOC action include the paints and coatings industries, agricultural pesticides and solvent cleaning processes. VOC’s are defined as those organic materials having a vapor pressure greater than 10 Pa at 20 °C or having corresponding volatility at other operating temperatures associated with industrial processes [3]. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) is a useful tool for screening for potential VOC candidates as well as the actual determination of vapor pressure of suspect materials. Both of these measurements are based on the determination of the boiling (or sublimation) temperature; the former under atmospheric conditions, the latter under reduced pressures. Figure 1 725 ° exo 180 C µ size: 10 l 580 prog: 10°C / min atm: N2 Heat Flow Heat Flow 2.25mPa 435 (326 psi) [ ----] Pressure (psi) endo 290 50 100 150 200 250 300 Temperature (°C) TA250 Nielson and co-workers [5] have observed that: • All organic solvents with boiling temperatures below 170 °C are classified as VOCs, and • No organics solvents with boiling temperatures greater than 260 °C are VOCs. -

Physical Model for Vaporization

Physical model for vaporization Jozsef Garai Department of Mechanical and Materials Engineering, Florida International University, University Park, VH 183, Miami, FL 33199 Abstract Based on two assumptions, the surface layer is flexible, and the internal energy of the latent heat of vaporization is completely utilized by the atoms for overcoming on the surface resistance of the liquid, the enthalpy of vaporization was calculated for 45 elements. The theoretical values were tested against experiments with positive result. 1. Introduction The enthalpy of vaporization is an extremely important physical process with many applications to physics, chemistry, and biology. Thermodynamic defines the enthalpy of vaporization ()∆ v H as the energy that has to be supplied to the system in order to complete the liquid-vapor phase transformation. The energy is absorbed at constant pressure and temperature. The absorbed energy not only increases the internal energy of the system (U) but also used for the external work of the expansion (w). The enthalpy of vaporization is then ∆ v H = ∆ v U + ∆ v w (1) The work of the expansion at vaporization is ∆ vw = P ()VV − VL (2) where p is the pressure, VV is the volume of the vapor, and VL is the volume of the liquid. Several empirical and semi-empirical relationships are known for calculating the enthalpy of vaporization [1-16]. Even though there is no consensus on the exact physics, there is a general agreement that the surface energy must be an important part of the enthalpy of vaporization. The vaporization diminishes the surface energy of the liquid; thus this energy must be supplied to the system. -

Equation of State for Benzene for Temperatures from the Melting Line up to 725 K with Pressures up to 500 Mpa†

High Temperatures-High Pressures, Vol. 41, pp. 81–97 ©2012 Old City Publishing, Inc. Reprints available directly from the publisher Published by license under the OCP Science imprint, Photocopying permitted by license only a member of the Old City Publishing Group Equation of state for benzene for temperatures from the melting line up to 725 K with pressures up to 500 MPa† MONIKA THOL ,1,2,* ERIC W. Lemm ON 2 AND ROLAND SPAN 1 1Thermodynamics, Ruhr-University Bochum, Universitaetsstrasse 150, 44801 Bochum, Germany 2National Institute of Standards and Technology, 325 Broadway, Boulder, Colorado 80305, USA Received: December 23, 2010. Accepted: April 17, 2011. An equation of state (EOS) is presented for the thermodynamic properties of benzene that is valid from the triple point temperature (278.674 K) to 725 K with pressures up to 500 MPa. The equation is expressed in terms of the Helmholtz energy as a function of temperature and density. This for- mulation can be used for the calculation of all thermodynamic properties. Comparisons to experimental data are given to establish the accuracy of the EOS. The approximate uncertainties (k = 2) of properties calculated with the new equation are 0.1% below T = 350 K and 0.2% above T = 350 K for vapor pressure and liquid density, 1% for saturated vapor density, 0.1% for density up to T = 350 K and p = 100 MPa, 0.1 – 0.5% in density above T = 350 K, 1% for the isobaric and saturated heat capaci- ties, and 0.5% in speed of sound. Deviations in the critical region are higher for all properties except vapor pressure. -

Determination of the Identity of an Unknown Liquid Group # My Name the Date My Period Partner #1 Name Partner #2 Name

Determination of the Identity of an unknown liquid Group # My Name The date My period Partner #1 name Partner #2 name Purpose: The purpose of this lab is to determine the identity of an unknown liquid by measuring its density, melting point, boiling point, and solubility in both water and alcohol, and then comparing the results to the values for known substances. Procedure: 1) Density determination Obtain a 10mL sample of the unknown liquid using a graduated cylinder Determine the mass of the 10mL sample Save the sample for further use 2) Melting point determination Set up an ice bath using a 600mL beaker Obtain a ~5mL sample of the unknown liquid in a clean dry test tube Place a thermometer in the test tube with the sample Place the test tube in the ice water bath Watch for signs of crystallization, noting the temperature of the sample when it occurs Save the sample for further use 3) Boiling point determination Set up a hot water bath using a 250mL beaker Begin heating the water in the beaker Obtain a ~10mL sample of the unknown in a clean, dry test tube Add a boiling stone to the test tube with the unknown Open the computer interface software, using a graph and digit display Place the temperature sensor in the test tube so it is in the unknown liquid Record the temperature of the sample in the test tube using the computer interface Watch for signs of boiling, noting the temperature of the unknown Dispose of the sample in the assigned waste container 4) Solubility determination Obtain two small (~1mL) samples of the unknown in two small test tubes Add an equal amount of deionized into one of the samples Add an equal amount of ethanol into the other Mix both samples thoroughly Compare the samples for solubility Dispose of the samples in the assigned waste container Observations: The unknown is a clear, colorless liquid. -

Physics, Chapter 17: the Phases of Matter

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Robert Katz Publications Research Papers in Physics and Astronomy 1-1958 Physics, Chapter 17: The Phases of Matter Henry Semat City College of New York Robert Katz University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/physicskatz Part of the Physics Commons Semat, Henry and Katz, Robert, "Physics, Chapter 17: The Phases of Matter" (1958). Robert Katz Publications. 165. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/physicskatz/165 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Research Papers in Physics and Astronomy at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Robert Katz Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 17 The Phases of Matter 17-1 Phases of a Substance A substance which has a definite chemical composition can exist in one or more phases, such as the vapor phase, the liquid phase, or the solid phase. When two or more such phases are in equilibrium at any given temperature and pressure, there are always surfaces of separation between the two phases. In the solid phase a pure substance generally exhibits a well-defined crystal structure in which the atoms or molecules of the substance are arranged in a repetitive lattice. Many substances are known to exist in several different solid phases at different conditions of temperature and pressure. These solid phases differ in their crystal structure. Thus ice is known to have six different solid phases, while sulphur has four different solid phases. -

Chapter 3 Equations of State

Chapter 3 Equations of State The simplest way to derive the Helmholtz function of a fluid is to directly integrate the equation of state with respect to volume (Sadus, 1992a, 1994). An equation of state can be applied to either vapour-liquid or supercritical phenomena without any conceptual difficulties. Therefore, in addition to liquid-liquid and vapour -liquid properties, it is also possible to determine transitions between these phenomena from the same inputs. All of the physical properties of the fluid except ideal gas are also simultaneously calculated. Many equations of state have been proposed in the literature with either an empirical, semi- empirical or theoretical basis. Comprehensive reviews can be found in the works of Martin (1979), Gubbins (1983), Anderko (1990), Sandler (1994), Economou and Donohue (1996), Wei and Sadus (2000) and Sengers et al. (2000). The van der Waals equation of state (1873) was the first equation to predict vapour-liquid coexistence. Later, the Redlich-Kwong equation of state (Redlich and Kwong, 1949) improved the accuracy of the van der Waals equation by proposing a temperature dependence for the attractive term. Soave (1972) and Peng and Robinson (1976) proposed additional modifications of the Redlich-Kwong equation to more accurately predict the vapour pressure, liquid density, and equilibria ratios. Guggenheim (1965) and Carnahan and Starling (1969) modified the repulsive term of van der Waals equation of state and obtained more accurate expressions for hard sphere systems. Christoforakos and Franck (1986) modified both the attractive and repulsive terms of van der Waals equation of state. Boublik (1981) extended the Carnahan-Starling hard sphere term to obtain an accurate equation for hard convex geometries. -

The Basics of Vapor-Liquid Equilibrium (Or Why the Tripoli L2 Tech Question #30 Is Wrong)

The Basics of Vapor-Liquid Equilibrium (Or why the Tripoli L2 tech question #30 is wrong) A question on the Tripoli L2 exam has the wrong answer? Yes, it does. What is this errant question? 30.Above what temperature does pressurized nitrous oxide change to a gas? a. 97°F b. 75°F c. 37°F The correct answer is: d. all of the above. The answer that is considered correct, however, is: a. 97ºF. This is the critical temperature above which N2O is neither a gas nor a liquid; it is a supercritical fluid. To understand what this means and why the correct answer is “all of the above” you have to know a little about the behavior of liquids and gases. Most people know that water boils at 212ºF. Most people also know that when you’re, for instance, boiling an egg in the mountains, you have to boil it longer to fully cook it. The reason for this has to do with the vapor pressure of water. Every liquid wants to vaporize to some extent. The measure of this tendency is known as the vapor pressure and varies as a function of temperature. When the vapor pressure of a liquid reaches the pressure above it, it boils. Until then, it evaporates until the fraction of vapor in the mixture above it is equal to the ratio of the vapor pressure to the total pressure. At that point it is said to be in equilibrium and no further liquid will evaporate. The vapor pressure of water at 212ºF is 14.696 psi – the atmospheric pressure at sea level. -

Molecular Corridors and Parameterizations of Volatility in the Chemical Evolution of Organic Aerosols

Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 3327–3344, 2016 www.atmos-chem-phys.net/16/3327/2016/ doi:10.5194/acp-16-3327-2016 © Author(s) 2016. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Molecular corridors and parameterizations of volatility in the chemical evolution of organic aerosols Ying Li1,2, Ulrich Pöschl1, and Manabu Shiraiwa1 1Multiphase Chemistry Department, Max Planck Institute for Chemistry, Mainz, Germany 2State Key Laboratory of Atmospheric Boundary Layer Physics and Atmospheric Chemistry (LAPC), Institute of Atmospheric Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China Correspondence to: Manabu Shiraiwa ([email protected]) Received: 23 September 2015 – Published in Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss.: 15 October 2015 Revised: 1 March 2016 – Accepted: 3 March 2016 – Published: 14 March 2016 Abstract. The formation and aging of organic aerosols (OA) 1 Introduction proceed through multiple steps of chemical reaction and mass transport in the gas and particle phases, which is chal- lenging for the interpretation of field measurements and lab- Organic aerosols (OA) consist of a myriad of chemical oratory experiments as well as accurate representation of species and account for a substantial mass fraction (20–90 %) OA evolution in atmospheric aerosol models. Based on data of the total submicron particles in the troposphere (Jimenez from over 30 000 compounds, we show that organic com- et al., 2009; Nizkorodov et al., 2011). They influence regional pounds with a wide variety of functional groups fall into and global climate by affecting radiative budget of the at- molecular corridors, characterized by a tight inverse cor- mosphere and serving as nuclei for cloud droplets and ice relation between molar mass and volatility. -

Liquid-Vapor Equilibrium in a Binary System

Liquid-Vapor Equilibria in Binary Systems1 Purpose The purpose of this experiment is to study a binary liquid-vapor equilibrium of chloroform and acetone. Measurements of liquid and vapor compositions will be made by refractometry. The data will be treated according to equilibrium thermodynamic considerations, which are developed in the theory section. Theory Consider a liquid-gas equilibrium involving more than one species. By definition, an ideal solution is one in which the vapor pressure of a particular component is proportional to the mole fraction of that component in the liquid phase over the entire range of mole fractions. Note that no distinction is made between solute and solvent. The proportionality constant is the vapor pressure of the pure material. Empirically it has been found that in very dilute solutions the vapor pressure of solvent (major component) is proportional to the mole fraction X of the solvent. The proportionality constant is the vapor pressure, po, of the pure solvent. This rule is called Raoult's law: o (1) psolvent = p solvent Xsolvent for Xsolvent = 1 For a truly ideal solution, this law should apply over the entire range of compositions. However, as Xsolvent decreases, a point will generally be reached where the vapor pressure no longer follows the ideal relationship. Similarly, if we consider the solute in an ideal solution, then Eq.(1) should be valid. Experimentally, it is generally found that for dilute real solutions the following relationship is obeyed: psolute=K Xsolute for Xsolute<< 1 (2) where K is a constant but not equal to the vapor pressure of pure solute. -

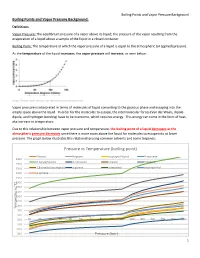

Pressure Vs Temperature (Boiling Point)

Boiling Points and Vapor Pressure Background Boiling Points and Vapor Pressure Background: Definitions Vapor Pressure: The equilibrium pressure of a vapor above its liquid; the pressure of the vapor resulting from the evaporation of a liquid above a sample of the liquid in a closed container. Boiling Point: The temperature at which the vapor pressure of a liquid is equal to the atmospheric (or applied) pressure. As the temperature of the liquid increases, the vapor pressure will increase, as seen below: https://www.chem.purdue.edu/gchelp/liquids/vpress.html Vapor pressure is interpreted in terms of molecules of liquid converting to the gaseous phase and escaping into the empty space above the liquid. In order for the molecules to escape, the intermolecular forces (Van der Waals, dipole- dipole, and hydrogen bonding) have to be overcome, which requires energy. This energy can come in the form of heat, aka increase in temperature. Due to this relationship between vapor pressure and temperature, the boiling point of a liquid decreases as the atmospheric pressure decreases since there is more room above the liquid for molecules to escape into at lower pressure. The graph below illustrates this relationship using common solvents and some terpenes: Pressure vs Temperature (boiling point) Ethanol Heptane Isopropyl Alcohol B-myrcene 290.0 B-caryophyllene d-Limonene Linalool Pulegone 270.0 250.0 1,8-cineole (eucalyptol) a-pinene a-terpineol terpineol-4-ol 230.0 p-cymene 210.0 190.0 170.0 150.0 130.0 110.0 90.0 Temperature (˚C) Temperature 70.0 50.0 30.0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 200 300 400 500 600 760 10.0 -10.0 -30.0 Pressure (torr) 1 Boiling Points and Vapor Pressure Background As a very general rule of thumb, the boiling point of many liquids will drop about 0.5˚C for a 10mmHg decrease in pressure when operating in the region of 760 mmHg (atmospheric pressure). -

Distillation Theory

Chapter 2 Distillation Theory by Ivar J. Halvorsen and Sigurd Skogestad Norwegian University of Science and Technology Department of Chemical Engineering 7491 Trondheim, Norway This is a revised version of an article published in the Encyclopedia of Separation Science by Aca- demic Press Ltd. (2000). The article gives some of the basics of distillation theory and its purpose is to provide basic understanding and some tools for simple hand calculations of distillation col- umns. The methods presented here can be used to obtain simple estimates and to check more rigorous computations. NTNU Dr. ing. Thesis 2001:43 Ivar J. Halvorsen 28 2.1 Introduction Distillation is a very old separation technology for separating liquid mixtures that can be traced back to the chemists in Alexandria in the first century A.D. Today distillation is the most important industrial separation technology. It is particu- larly well suited for high purity separations since any degree of separation can be obtained with a fixed energy consumption by increasing the number of equilib- rium stages. To describe the degree of separation between two components in a column or in a column section, we introduce the separation factor: ()⁄ xL xH S = ------------------------T (2.1) ()x ⁄ x L H B where x denotes mole fraction of a component, subscript L denotes light compo- nent, H heavy component, T denotes the top of the section, and B the bottom. It is relatively straightforward to derive models of distillation columns based on almost any degree of detail, and also to use such models to simulate the behaviour on a computer.