Ottawa Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canada's Parliament

Foreign Policy White Papers and the Role of Canada’s Parliament: Paradoxical But Not Without Potential Gerald J. Schmitz Principal analyst, international affairs Parliamentary Information and Research Service Library of Parliament, Ottawa Annual Meeting of the Canadian Political Science Association University of Western Ontario, London Panel on “International and Defence Policy Review” 3 June 2005 Note: This paper developed out of remarks to a conference in Quebec City in May 2004 on the subject of white-paper foreign policy management processes, and is a pre- publication draft of an article for the fall 2005 issue of Études internationales. The views expressed are the author’s alone. Please do not cite without permission. Introduction to the Paradoxical Actor on the Hill The observations that follow draw on several decades of direct experience working with that paradoxical, and sometimes overlooked, actor in the foreign policy development process, namely Canada’s Parliament. During that time concerns about the alleged weaknesses of parliamentary oversight of the executive have become a commonplace complaint. They seem also to be a staple assumption in the academic discourse on Canadian foreign policy, when the legislative role merits any mention at all. (Frequently it does not.) Yet if one believes the renewed rhetoric emanating from high places about redressing “democratic deficits” in the Canadian body politic, this was all supposed to change. At the end of 2003, a new prime minister ushering in a new management regime, or at least a different style of governing, said that he and his government were committed to changing the way things work in Ottawa. -

Report on Transformation: a Leaner NDHQ?

• INDEPENDENT AND INFORMED • AUTONOME ET RENSEIGNÉ ON TRACK The Conference of Defence Associations Institute • L’Institut de la Conférence des Associations de la Défense Autumn 2011 • Volume 16, Number 3 Automne 2011 • Volume 16, Numéro 3 REPORT ON TRANSFORMATION: A leaner NDHQ? Afghanistan: Combat Mission Closure Reflecting on Remembrance ON TRACK VOLUME 16 NUMBER 3: AUTUMN / AUTOMNE 2011 PRESIDENT / PRÉSIDENT Dr. John Scott Cowan, BSc, MSc, PhD VICE PRESIDENT / VICE PRÉSIDENT Général (Ret’d) Raymond Henault, CMM, CD CDA INSTITUTE BOARD OF DIRECTORS LE CONSEIL D’ADMINISTRATION DE L’INSTITUT DE LA CAD EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR / DIRECTEUR EXÉCUTIF Colonel (Ret) Alain M. Pellerin, OMM, CD, MA Admiral (Ret’d) John Anderson SECRETARY-TREASURER / SECRÉTAIRE TRÉSORIER Mr. Thomas d’Aquino Lieutenant-Colonel (Ret’d) Gordon D. Metcalfe, CD Dr. David Bercuson HONOURARY COUNSEL / AVOCAT-CONSEIL HONORAIRE Dr. Douglas Bland Mr. Robert T. Booth, QC, B Eng, LL B Colonel (Ret’d) Brett Boudreau DIRECTOR OF RESEARCH / Dr. Ian Brodie DIRECTEUR DE LA RECHERCHE Mr. Paul Chapin, MA Mr. Thomas S. Caldwell Mr. Mel Cappe PUBLIC AFFAIRS / RELATIONS PUBLIQUES Captain (Ret’d) Peter Forsberg, CD Mr. Jamie Carroll Dr. Jim Carruthers DEFENCE POLICY ANALYSTS / ANALYSTES DES POLITIQUES DE DÉFENSE Mr. Paul H. Chapin Ms. Meghan Spilka O’Keefe, MA Mr. Terry Colfer Mr. Arnav Manchanda, MA M. Jocelyn Coulon Mr. Dave Perry, MA Dr. John Scott Cowan PROJECT OFFICER / AGENT DE PROJET Mr. Dan Donovan Mr. Paul Hillier, MA Lieutenant-général (Ret) Richard Evraire Conference of Defence Associations Institute Honourary Lieutenant-Colonel Justin Fogarty 151 Slater Street, Suite 412A Ottawa ON K1P 5H3 Colonel, The Hon. -

Canada and the Kosovo Crisis: an Agenda for Intervention

Canada and the Kosovo Crisis: An Agenda for Intervention Canada and the Kosovo Crisis: An Agenda for Intervention Michael W. Manulak Centre for International Relations, Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada 2011 Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Manulak, Michael W., 1983- Canada and the Kosovo crisis : an agenda for intervention / Michael W. Manulak. (Martello papers, ISSN 1183-3661 ; 36) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-1-55339-245-3 1. Kosovo War, 1998-1999—Participation, Canadian. 2. Canada— Military policy. I. Queen’s University (Kingston, Ont.). Centre for International Relations II. Title. III. Series: Martello papers ; 36 DR2087.6.F652C3 2010 949.7103 C2010-907064-X © Copyright 2011 Martello Paper Series Queen’s University’s Centre for International Relations (QCIR) is pleased to present the latest in its series of monographs, the Martello Papers. Taking their name from the distinctive towers built during the nineteenth century to defend Kingston, Ontario, these papers cover a wide range of topics and issues in foreign and defence policy, and in the study of international peace and security. How governments make decisions in times of crisis is a topic which has long fascinated both theorists and practitioners of international politics. Michael Manulak’s study of the Canadian government’s decision to take part in NATO’s use of force against Serbia in the spring of 1999 deploys a novel social-scientific method to dissect the process whereby that decision was made. In that respect this paper descends from a long line of inquiry going back to the 1960s and the complex flow-charts designed by “scientific” students of foreign policy. -

September 16, 2020 Minister of Foreign Affairs of the People’S Republic of China Wang Yi

September 16, 2020 Minister of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China Wang Yi Re: The Immediate Release of and Justice for Dr Wang Bingzhang Dear Minister Wang Yi, We write to bring to your attention the dire situation of Dr Wang Bingzhang, a Chinese national with a strong Canadian connection languishing in solitary confinement in Shaoguan Prison. In 1979, the Chinese Government sponsored Dr Wang’s studies at McGill University’s Faculty of Medicine. In 1982, Dr Wang became the first Chinese national to be awarded a PhD in North America. Newspapers in China and around the world praised his monumental accomplishments. Dr Wang then decided to forego his promising career in medicine to dedicate his life to human rights, firmly believing that self-sacrifice for his country was the most noble value. He identified as a Chinese patriot, and should have returned home a hero. Instead, in 2002, he was kidnapped in Vietnam and forcibly brought to China. It was only after five months of incommunicado detention that he was notified of the charges brought against him. Not once was he permitted to contact his family or a lawyer. At trial, Dr Wang was denied the opportunity to speak or present evidence, and no credible evidence or live witness testimony was presented against him. Moreover, the trial was closed to the public and lasted only half a day. The Shenzhen People’s Intermediate Court sentenced Dr Wang to life in solitary confinement. Dr Wang appealed the decision, but the sentence was upheld a month later, where he was again barred from speaking. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS THE CHRETIEN LEGACY Introduction .................................................. i The Chr6tien Legacy R eg W hitaker ........................................... 1 Jean Chr6tien's Quebec Legacy: Coasting Then Stickhandling Hard Robert Y oung .......................................... 31 The Urban Legacy of Jean Chr6tien Caroline Andrew ....................................... 53 Chr6tien and North America: Between Integration and Autonomy Christina Gabriel and Laura Macdonald ..................... 71 Jean Chr6tien's Continental Legacy: From Commitment to Confusion Stephen Clarkson and Erick Lachapelle ..................... 93 A Passive Internationalist: Jean Chr6tien and Canadian Foreign Policy Tom K eating ......................................... 115 Prime Minister Jean Chr6tien's Immigration Legacy: Continuity and Transformation Yasmeen Abu-Laban ................................... 133 Renewing the Relationship With Aboriginal Peoples? M ichael M urphy ....................................... 151 The Chr~tien Legacy and Women: Changing Policy Priorities With Little Cause for Celebration Alexandra Dobrowolsky ................................ 171 Le Petit Vision, Les Grands Decisions: Chr~tien's Paradoxical Record in Social Policy M ichael J. Prince ...................................... 199 The Chr~tien Non-Legacy: The Federal Role in Health Care Ten Years On ... 1993-2003 Gerard W . Boychuk .................................... 221 The Chr~tien Ethics Legacy Ian G reene .......................................... -

Canadian Arctic Sovereignty and Security

Journal of Military and Strategic Studies, Spring 2009, Vol. 11, Issue 3. IN DEFENCE OF DEFENCE: CANADIAN ARCTIC SOVEREIGNTY AND SECURITY LCol. Paul Dittmann, 3 Canadian Forces Flying Training School Since the Second World War, Canada‟s armed forces have often represented the most prominent federal organization in the occupation and use of the Canadian Arctic. Economic development in the region came in fits and starts, hindered by remoteness and the lack of any long-term industry base. Today the Arctic‟s resource potential, fuelled by innovative technological advances, has fed to demands for infrastructure development. New opportunities in Canada‟s Arctic have, in turn, influenced a growing young population and their need for increased social development. Simultaneously, the fragile environment becomes a global focal point as the realities of climate change are increasingly accepted, diplomatically drawing together circumpolar nations attempting to address common issues. A unipolar world order developed with the geopolitical imbalance caused by the fall of the Soviet Union. This left the world‟s sole superpower, the United States (US), and its allies facing increased regional power struggles, international terrorism, and trans-national crime. Given the combination of tremendous growth in the developing world, its appetite for commodities, and the accessibility to resource-rich polar regions facilitated by climate change, Canada faces security and sovereignty issues that are both remnants of the Cold War era and newly emerging. The response to these challenges has been a resurgence of military initiatives to empower Canadian security and sovereignty in the region. Defence-based initiatives ©Centre for Military and Strategic Studies, 2009. -

Bill C-55, Public Safety Act 2002

July 3, 2002 Hon. Martin Cauchon, P.C., M.P. Hon. David Collenette, P.C., M.P. Minister of Justice Minister of Transport Department of Justice Department of Transport East Memorial Building Tower C, Place de Ville 284 Wellington Street 29th floor, 330 Sparks Street Ottawa Ontario Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0A6 K1A 0N5 Hon. John McCallum, P.C., M.P. Hon. Lawrence MacAulay, P.C., M.P. Minister of National Defence Solicitor General Department of National Defence Department of the Solicitor General 101 Colonel By Drive 340 Laurier Avenue West Ottawa, Ontario Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0K2 K1A 0P8 Hon. Denis Coderre, P.C., M.P. Minister of Citizenship and Immigration Department of Citizenship and Immigration Jean Edmonds South Tower, 365 Laurier Avenue West, 21st Floor Ottawa, Ontario K1A 1L1 Dear Ministers: Re: Bill C-55, Public Safety Act 2002 The Canadian Bar Association (CBA) is pleased to have the opportunity to provide its comments concerning Bill C-55, Public Safety Act, 2002. Much of the Bill is similar to its predecessor – Bill C-42, Public Safety Act. To the extent that Bill C-55 has not addressed our concerns, we rely on our previous submission concerning Bill C-42 (a copy of which is attached), which we provided to the government in February 2002. This letter provides additional comments which principally address the differences between Bill C-42 and Bill C-55. Airline Passenger Information Bill C-42 permitted collection and use of airline passenger information in two contexts – transportation security (proposed section 4.82 of the Aeronautics Act, in clause 5 of Bill C-42) and immigration (proposed section 88.1 of the Immigration Act, in clause 69 of Bill C-42, which Page 2 applied to all transportation companies). -

Ministerial Error and the Political Process: Is There a Duty to Resign? Stuart James Whitley

Ministerial Error and the Political Process: Is there a Duty to Resign? Stuart James Whitley, QC* In practice, it is seldom very hard to do one’s duty when one knows what it is. But it is sometimes exceedingly difficult to find this out. - Samuel Butler (1912) “First Principles” Note Books The honourable leader is engaged continuously in the searching of his (sic) duty. Because he is practicing the most powerful and most dangerous of the arts affecting, however humbly, the quality of life and the human search for meaning, he ought to have – if honourable, he has to have – an obsession with duty. What are his responsibilities? -Christopher Hodgkinson (1983) The Philosophy of Leadership Abstract: This article examines the nature of the duty to resign for error in the ministerial function. It examines the question of resignation as a democratic safeguard and a reflection of a sense of honour among those who govern. It concludes that there is a duty to resign for misleading Parliament, for serious personal misbehaviour, for a breach of collective responsibility, for serious mismanagement of the department for which they are responsible, and for violations of the rule of law. The obligation is owed generally to Parliament, and specifically to the Prime Minister, who has the constitutional authority in any event to dismiss a minister. The nature of the obligation is a constitutional convention, which can only be enforced by political action, though a breach of the rule of law is reviewable in the courts and may effectively disable a minister. There appears to be uneven historical support for the notion that ministerial responsibility includes the duty to resign for the errors of officials except in very narrow circumstances. -

Fishing for a Solution: Canada’S Fisheries Relations with the European Union, 1977–2013

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2014 Fishing for a Solution: Canada’s Fisheries Relations with the European Union, 1977–2013 Barry, Donald; Applebaum, Bob; Wiseman, Earl University of Calgary Press Barry, D., Applebaum, B. & Wiseman, E. "Fishing for a Solution: Canada’s Fisheries Relations with the European Union, 1977–2013". Beyond boundaries: Canadian defence and strategic studies series; 5. University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2014. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/50142 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca FISHING FOR A SOLUTION: CANADA’S FISHERIES RELATIONS WITH THE EUROPEAN UNION, 1977–2013 Donald Barry, Bob Applebaum, and Earl Wiseman ISBN 978-1-55238-779-5 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. -

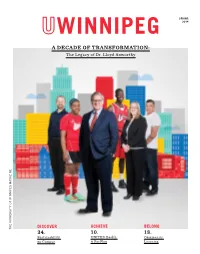

A DECADE of TRANSFORMATION —INSIDE & out the Legacy of Dr

SPRING WINNIPEG 2014 A DECADE OF TRANSFORMatION: The Legacy of Dr. Lloyd Axworthy DISCOVER ACHIEVE BELONG THE UNIVERSITY OF WINNIPEG MAGAZINE 34. 10. 18. Sustainability UNITED Health Community on Campus & RecPlex Learning Reward yourself. Get the BMO® University of Winnipeg MasterCard.®* Reward yourself with 1 AIR MILES®† reward mile for every $20 spent or 0.5% CashBack® and pay no annual fee1,2. Give something back With every purchase you make, BMO Bank of Montreal® makes a contribution to help support the development of programs and services for alumni, at no additional cost to you. Apply now! 1-800-263-2263 Alumni: bmo.com/winnipeg Student: bmo.com/winnipegspc Call 1-800-263-2263 to switch your BMO MasterCard to a BMO University of Winnipeg MasterCard. 1 Award of AIR MILES reward miles is made for purchases charged to your Account (less refunds) and is subject to the Terms and Conditions of your BMO MasterCard Cardholder Agreement. The number of reward miles will be rounded down to the nearest whole number. Fractions of reward miles will not be awarded. 2 Ongoing interest rates, interest-free grace period, annual fees and all other applicable fees are subject to change. See your branch, call the Customer Contact Center at 1-800-263-2263, or visit bmo.com/mastercard for current rates.® Registered trade-marks of Bank of Montreal. ®* MasterCard is a registered trademark of MasterCard International Incorporated. ®† Trademarks of AIR MILES International Trading B.V. Used under license by LoyaltyOne, Inc. and Bank of Montreal. Docket #: 13-321 Ad or Trim Size: 8.375" x 10.75" Publication: The Journal (Univ of Winnipeg FILE COLOURS: Type Safety: – Alumni Magazine) Description of Ad: U. -

312 Canadian Foreign Policy the Chrétien-Martin Years Lecture 11 POL 312Y Canadian Foreign Policy Professor John Kirton University of Toronto

312 Canadian Foreign Policy The Chrétien-Martin Years Lecture 11 POL 312Y Canadian Foreign Policy Professor John Kirton University of Toronto Introduction: The Chrétien-Martin Eras Assessed In interpreting Canadian foreign policy during the Chrétien-Martin years, scholars face unusual difficulty (Smith 1995). Unlike Pierre Trudeau and Kim Campbell before him, Prime Minister Jean Chrétien did not set forth during his earlier life, his first election campaign, or his first year in office a comprehensive personal vision of what his foreign policy would be. His definitive “Statement” on foreign policy, unveiled on February 7, 1995, appeared to have been overtaken within a year by a very different doctrine from his new foreign minister Lloyd Axworthy, and ultimately by the “Dialogue” report released by foreign minister Bill Graham in June 2003. Moreover, Chrétien’s foreign policy doctrines, resource distributions, and key decisions were designed at the start to deal with the bright post–Cold War world abroad and the grim world of deficits, debt, and disunity at home. But by the end of the Chrétien decade, his Liberal Party successor Paul Martin had to cope with the great reversal of a grim post 9/11 world at war abroad and a strong, secure, cohesive Canada at home. Martin’s effort to do so, in his April 2005 International Policy Statement, demonstrated the difficulties of doctrinally doing so. The Chrétien Decade: The Debate In assessing Jean Chrétien’s decade as Prime Minister from October 25, 1993 to December 12, 2003, scholars offer three major competing schools of thought. The first sees LI’s disappointing continuity, as once again the prospect of immediate change from a new prime minister was quickly snatched away. -

Canada's Inadequate Response to Terrorism: the Need for Policy

Fraser Institute Digital Publication February 2006 Canada’s Inadequate Response to Terrorism: The Need for Policy Reform by Martin Collacott CONTENTS Executive Summary / 2 Introduction / 3 The Presence of Terrorists in Canada / 4 An Ineffective Response to the Terrorism Threat / 6 New Legislation and Policies / 16 Problems Dealing with Terrorists in Canada / 21 Where Security Needs To Be Strengthened / 27 Problems with the Refugee Determination System / 30 Permanent Residents and Visitors’ Visas / 52 Canada Not Taking a Tough Line on Terrorism / 60 Making Clear What We Expect of Newcomers / 63 Working With the Muslim Community / 69 Concluding Comments and Recommendations / 80 Appendix A: Refugee Acceptance Rates / 87 References / 88 About the Author / 100 About this Publication / 101 About The Fraser Institute / 102 Canada’s Inadequate Response to Terrorism 2 Executive Summary Failure to exercise adequate control over the entry and the departure of non-Canadians on our territory has been a significant factor in making Canada a destination for terror- ists. The latter have made our highly dysfunctional refugee determination system the channel most often used for gaining entry. A survey that we made based on media reports of 25 Islamic terrorists and suspects who entered Canada as adults indicated that 16 claimed refugee status, four were admitted as landed immigrants and the channel of entry for the remaining five was not identified. Making a refugee claim is used by both ter- rorists and criminals as a means of rendering their removal from the country more difficult. In addition to examining specific shortcomings of current policies, this paper will also look at the reasons why the government has not rectified them.