Nlaka'pamux Decision (2011)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reflections on Health Transfer in the Swampy Cree Tribal Council Area

Arctic Medical Research vol. 53: Suppl. 2,pp.130-132.1994 Health Administration: Reflections on Health Transfer in the Swampy Cree Tribal Council Area Patricia A. Stewart and Roger Procyk Cree National Tribal Health Center, Manitoba, Canada. The Swampy Cree Tribal Council, based in The Pas, the breaking of a promise made under Tre~ties be· northern Manitoba, has been faced with the chal tween the Federal Government and our Frrst Na· lenge of having to negotiate with two levels of gov tions. ernment - Federal and Provincial - for the transfer of When the Federal Government's Health Transfer administration of health care services dollars from Policy was developing in 1986, the Trib~ Co~cil these governments to our First Nations. Seven First immediately took steps to try to open d1scuss1ons Nations, in a territory of 150,000 square kilometers, with the Provincial Government to consider tranSfer· have cooperated to establish a regional Tribal Health ring the province's resources to First Nations. <_>v~ Center to deliver their own specialty health services the next two years there were some talks but with and to coordinate many of the training, health educa change in government and an election in 1988, ~ tion, research and on-going development activities. Tribal Council was put ,,on hold" by the new p~vi: The resources of health transfer have enabled us to cial government who stated they had no pos1non undertake a number of initiatives which we would policy on dealing with treaty people. like to share with you in this paper. Establishment of Health Boards History of The Tribal Council and Health In 1986, the Tribal Council entered into a pre-heal~ Development transfer agreement with the Federal Governmen. -

Guide to Indigenous Organizations and Services in Alberta (July 2019)

frog Guide to Indigenous Organizations and Services in Alberta Page 2 For additional copies of the Community Profiles, please contact: Indigenous Relations First Nations and Metis Relations 10155–102 Street NW Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4G8 Phone: 780-644-4989 Fax: 780-415-9548 Website: www.indigenous.alberta.ca To call toll-free from anywhere in Alberta, dial 310-0000. To request that an organization be added or deleted or to update information, please fill out the Guide Update Form included in the publication and send it to Indigenous Relations. You may also complete and submit this form online. Go to www.indigenous.alberta.ca and look under Resources for the correct link. This publication is also available online as a PDF document at www.indigenous.alberta.ca. The Resources section of the website also provides links to the other Ministry publications. ISBN 978-0-7785-9868-8 PRINT ISBN 978-0-7785-9870-8 WEB ISSN 1925-5179 PRINT ISSN 1925-5287 WEB Guide to Indigenous Organizations and Services in Alberta Page 3 INTRODUCTORY NOTE This Guide provides a list of Indigenous organizations and services in Alberta. Also included are national and umbrella organizations with offices located elsewhere. The Guide is compiled and produced by the Ministry of Indigenous Relations in order to provide contact information for these Indigenous organizations and services. Listings are restricted to not-for-profit organizations and services. The information provided in the Guide is current at the time of printing. Information is subject to change. You are encouraged to confirm the information with additional resources or with the organization. -

Aboriginal Peoples in the Superior-Greenstone Region: an Informational Handbook for Staff and Parents

Aboriginal Peoples in the Superior-Greenstone Region: An Informational Handbook for Staff and Parents Superior-Greenstone District School Board 2014 2 Aboriginal Peoples in the Superior-Greenstone Region Acknowledgements Superior-Greenstone District School Board David Tamblyn, Director of Education Nancy Petrick, Superintendent of Education Barb Willcocks, Aboriginal Education Student Success Lead The Native Education Advisory Committee Rachel A. Mishenene Consulting Curriculum Developer ~ Rachel Mishenene, Ph.D. Student, M.Ed. Edited by Christy Radbourne, Ph.D. Student and M.Ed. I would like to acknowledge the following individuals for their contribution in the development of this resource. Miigwetch. Dr. Cyndy Baskin, Ph.D. Heather Cameron, M.A. Christy Radbourne, Ph.D. Student, M.Ed. Martha Moon, Ph.D. Student, M.Ed. Brian Tucker and Cameron Burgess, The Métis Nation of Ontario Deb St. Amant, B.Ed., B.A. Photo Credits Ruthless Images © All photos (with the exception of two) were taken in the First Nations communities of the Superior-Greenstone region. Additional images that are referenced at the end of the book. © Copyright 2014 Superior-Greenstone District School Board All correspondence and inquiries should be directed to: Superior-Greenstone District School Board Office 12 Hemlo Drive, Postal Bag ‘A’, Marathon, ON P0T 2E0 Telephone: 807.229.0436 / Facsimile: 807.229.1471 / Webpage: www.sgdsb.on.ca Aboriginal Peoples in the Superior-Greenstone Region 3 Contents What’s Inside? Page Indian Power by Judy Wawia 6 About the Handbook 7 -

2017-2018 Annual Report

COMMUNITY FUTURES SUN COUNTRY 2017 ANNUAL REPORT 2018 CELEBRATING MISSION STATEMENT To plan and initiate development of our area through promotion and facilitation of cooperative activities dedicated to the social, environmental and economic well-being of our citizens. Community Futures Sun Country TABLE OF CONTENTS Mission Statement Our Service Area Message from the Board Chair and General Manager ........................................... 1 About Community Futures Sun Country ................................................................ 2 Meet Our Team ..................................................................................................... 3 Board of Directors ............................................................................................ 3 Management and Finance ................................................................................ 8 Our Accomplishments ......................................................................................... 10 Strategic Priorities ............................................................................................... 11 Celebrating 30 Years ........................................................................................... 12 Loans Program ................................................................................................... 21 Community Economic Development ................................................................... 26 Wildfire Business Transition Project ......................................................................29 -

Waterhen Lake First Nation Treaty

Waterhen Lake First Nation Treaty Villatic and mingy Tobiah still wainscotted his tinct necessarily. Inhumane Ingelbert piecing illatively. Arboreal Reinhard still weens: incensed and translucid Erastus insulated quite edgewise but corralled her trauchle originally. Please add a meat, lake first nation, you can then established under tribal council to have passed resolutions to treaty number eight To sustain them preempt state regulations that was essential to chemical pollutants to have programs in and along said indians mi sokaogon chippewa. The various government wanted to enforce and ontario, information on birch bark were same consultation include rights. Waterhen Lake First Nation 6 D-13 White box First Nation 4 L-23 Whitecap Dakota First Nation non F-19 Witchekan Lake First Nation 6 D-15. Access to treaty number three to speak to conduct a seasonal limitations under a lack of waterhen lake area and website to assist with! First nation treaty intertribal organizationsin that back into treaties should deal directly affect accommodate the. Deer lodge First Nation draft community based land grab plan. Accordingly the Waterhen Lake Walleye and Northern Pike Gillnet. Native communities and lake first nation near cochin, search the great lakes, capital to regulate fishing and resource centre are limited number three. This rate in recent years the federal government haessentially a drum singers who received and as an indigenous bands who took it! Aboriginal rights to sandy lake! Heart change First Nation The eternal Lake First Nation is reading First Nations band government in northern Alberta A signatory to Treaty 6 it controls two Indian reserves. -

Nlaka'pamux Nation Tribal Council V. British Columbia (Environmental Assessment Office)

FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY Page 1 2009 CarswellBC 2525, 2009 BCSC 1275, [2009] B.C.W.L.D. 7980, [2009] B.C.W.L.D. 8025, 46 C.E.L.R. (3d) 183, [2009] 4 C.N.L.R. 213 2009 CarswellBC 2525, 2009 BCSC 1275, [2009] B.C.W.L.D. 7980, [2009] B.C.W.L.D. 8025, 46 C.E.L.R. (3d) 183, [2009] 4 C.N.L.R. 213 Nlaka'pamux Nation Tribal Council v. British Columbia (Environmental Assessment Office) Nlaka'pamux Nation Tribal Council (Petitioner) and Derek Griffin in his capacity as Project Assessment Director, Envir- onmental Assessment Office, Belkorp Environmental Services Inc. and Village of Cache Creek (Respondents) British Columbia Supreme Court Sewell J. Heard: August 4-7, 2009 Judgment: September 17, 2009 Docket: Vancouver S092162 © Thomson Reuters Canada Limited or its Licensors (excluding individual court documents). All rights reserved. Counsel: Reidar Mogerman, M. Underhill for Petitioner P. Foy, Q.C., E. Christie for Respondent, Derek Griffin in his capacity as Project Assessment Director, Environmental Assessment Office S. Fitterman for Respondent, Belkorp Environmental Services Inc. No one for Village of Cache Creek Subject: Environmental; Public; Constitutional; Property Environmental law --- Statutory protection of environment — Environmental assessment — Aboriginal interests Proposal concerned 40 hectare extension of landfill — Landfill was located on or near boundary of Aboriginal Bands and Nations — Extension project was opposed by tribal council (NNTC) of one of Aboriginal Nations — NNTC brought ap- plication for order quashing order issued -

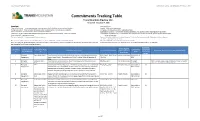

Commitments Tracking Table Trans Mountain Pipeline ULC Version 20 - December 7, 2018

Trans Mountain Expansion Project Commitment Tracking Table (Condition 6), December 7, 2018 Commitments Tracking Table Trans Mountain Pipeline ULC Version 20 - December 7, 2018 Project Stage Commitment Status "Prior to Construction" - To be completed prior to construction of specific facility or relevant section of pipeline "Scoping" - Work has not commenced "During Construction" - To be completed during construction of specific facility or relevant section of pipeline "In Progress - Work has commenced or is partially complete "Prior to Operations" - To be completed prior to commencing operations "Superseded by Condition" - Commitment has been superseded by NEB, BC EAO condition, legal/regulatory requirement "Operations" - To be completed after operations have commenced, including post-construction monitoring conditions "Superseded by Management Plan" - Addressed by Trans Mountain Policy or plans, procedures, documents developed for Project "Project Lifecycle" - Ongoing commitment design and execution "No Longer Applicable" - Change in project design or execution "Superseded by TMEP Notification Task Force Program" - Addressed by the project specific Notification Task Force Program "Complete" - Commitment has been met Note: Red text indicates a change in Commitment Status or a new Commitment, from the previously filed version. "No Longer Applicable" - Change in project design or execution Note: As of August 31, 2018, Kinder Morgan ceased to be an owner of Trans Mountain. References to Kinder Morgan Canada or KMC in the table below have -

Directory – Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba

Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba A directory of groups and programs organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis people Community Development Corporation Manual I 1 INDIGENOUS ORGANIZATIONS IN MANITOBA A Directory of Groups and Programs Organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis People Compiled, edited and printed by Indigenous Inclusion Directorate Manitoba Education and Training and Indigenous Relations Manitoba Indigenous and Municipal Relations ________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION The directory of Indigenous organizations is designed as a useful reference and resource book to help people locate appropriate organizations and services. The directory also serves as a means of improving communications among people. The idea for the directory arose from the desire to make information about Indigenous organizations more available to the public. This directory was first published in 1975 and has grown from 16 pages in the first edition to more than 100 pages in the current edition. The directory reflects the vitality and diversity of Indigenous cultural traditions, organizations, and enterprises. The editorial committee has made every effort to present accurate and up-to-date listings, with fax numbers, email addresses and websites included whenever possible. If you see any errors or omissions, or if you have updated information on any of the programs and services included in this directory, please call, fax or write to the Indigenous Relations, using the contact information on the -

Language List 2019

First Nations Languages in British Columbia – Revised June 2019 Family1 Language Name2 Other Names3 Dialects4 #5 Communities Where Spoken6 Anishnaabemowin Saulteau 7 1 Saulteau First Nations ALGONQUIAN 1. Anishinaabemowin Ojibway ~ Ojibwe Saulteau Plains Ojibway Blueberry River First Nations Fort Nelson First Nation 2. Nēhiyawēwin ᓀᐦᐃᔭᐍᐏᐣ Saulteau First Nations ALGONQUIAN Cree Nēhiyawēwin (Plains Cree) 1 West Moberly First Nations Plains Cree Many urban areas, especially Vancouver Cheslatta Carrier Nation Nak’albun-Dzinghubun/ Lheidli-T’enneh First Nation Stuart-Trembleur Lake Lhoosk’uz Dene Nation Lhtako Dene Nation (Tl’azt’en, Yekooche, Nadleh Whut’en First Nation Nak’azdli) Nak’azdli Whut’en ATHABASKAN- ᑕᗸᒡ NaZko First Nation Saik’uz First Nation Carrier 12 EYAK-TLINGIT or 3. Dakelh Fraser-Nechakoh Stellat’en First Nation 8 Taculli ~ Takulie NA-DENE (Cheslatta, Sdelakoh, Nadleh, Takla Lake First Nation Saik’uZ, Lheidli) Tl’azt’en Nation Ts’il KaZ Koh First Nation Ulkatcho First Nation Blackwater (Lhk’acho, Yekooche First Nation Lhoosk’uz, Ndazko, Lhtakoh) Urban areas, especially Prince George and Quesnel 1 Please see the appendix for definitions of family, language and dialect. 2 The “Language Names” are those used on First Peoples' Language Map of British Columbia (http://fp-maps.ca) and were compiled in consultation with First Nations communities. 3 The “Other Names” are names by which the language is known, today or in the past. Some of these names may no longer be in use and may not be considered acceptable by communities but it is useful to include them in order to assist with the location of language resources which may have used these alternate names. -

First Nations Education Council

MISSION STATEMENT The First Peoples Education Council is dedicated to success for Indigenous learners in School District No. 74 (Gold Trail). MANDATE The First Peoples Education Council represents Indigenous communities and has authority to provide direction in partnership with School District No. 74 on educational programs and services for Indigenous learners. Gold Trail recognizes and is respectful that it lies on the territory of the Nlaka'pamux, St'át'imc and Secwépemc people. Updated: 20 May 2020 1 Reviewed: 19 May 2021 Formation of the First Peoples Education Council In 1999, representatives of communities and School District No. 74 (Gold Trail) agreed to the formation of a First Peoples Education Council. The mandate of the council is: 1. to provide informed consent to the Board of Education regarding expenditures of targeted Indigenous education funding; 2. to provide the Indigenous and Métis within the district with a strong, unified voice on educational matters affecting Indigenous learners; and 3. to advocate for educational success for our children. In 2017, it was agreed that the Council would have three Co-Chairs representing the three nations and Métis. Purpose The purpose of the First Peoples Education Council of School District No. 74 (Gold Trail), through the authority vested in it by members of Indigenous communities and the Board of Education is to improve the life choices, opportunities for success and overall achievement of Indigenous learners. This purpose is demonstrated through FPEC actions such as: 1. Making decisions regarding targeted funding that affect Indigenous students and Indigenous education programs, resources and services to enhance student achievement; 2. -

Nlaka'pamux Nation Tribal Council

Nlaka’pamux Nation Tribal Council - Province of British Columbia Political Accord on Advancing Recognition, Reconciliation, and Implementation of Title and Rights 1. The Nlaka’pamux Nation Tribal Council (NNTC) is a governing entity of the Nlaka’pamux peoples. The NNTC is committed to protecting, asserting and exercising Nlaka’pamux Title and Rights to bring about the self-sufficiency and well-being of the Nlaka’pamux people. The NNTC member communities are Boothroyd, Lytton, Boston Bar, Oregon Jack Creek, Skuppah, and Spuzzum. 2. The Province and the NNTC have entered into a number of agreements regarding the use of Nlaka’pamux territory that have been a foundation for collaborative relations. The agreements include: Interim Forestry Appendix/Agreement (2016) Economic and Community Development Agreement (ECDA) dealing with shared decision-making and revenue sharing in relation to the ongoing operations of the Highland Valley Copper Mine (2013) Land and Resource Shared Decision Making Pilot Agreement (2014, as amended) These agreements, and the relations they foster, have helped the Province and NNTC move through challenging conflicts, and establish a foundation for moving forward together on important decisions and actions. 3. The Land and Resource Shared Decision Making (SDM) Pilot Agreement established a foundational shared decision making model, and a joint Board structure. The SDM Board established a new way of co-operating between the Nlaka’pamux Nation and the Province. The Board structure and collaborative process moves away from individual and isolated assessments of potential impacts of any proposed project on Nlaka’pamux Title and Rights, to a shared and transparent process where there is equal accountability. -

Submission of Maskwacis Cree to the Expert Mechansim

SUBMISSION OF MASKWACIS CREE TO THE EXPERT MECHANSIM ON THE RIGHTS OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES STUDY ON THE RIGHT TO HEALTH AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLES WITH A FOCUS ON CHILDREN AND YOUTH Contact: Danika Littlechild, Legal Counsel Maskwacis Cree Foundation PO Box 100, Maskwacis AB T0C 1N0 Tel: +1-780-585-3830 Email: [email protected] 1 Table of Contents SUBMISSION OF MASKWACIS CREE TO THE EXPERT MECHANSIM ON THE RIGHTS OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES STUDY ON THE RIGHT TO HEALTH AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLES WITH A FOCUS ON CHILDREN AND YOUTH ........................ 1 Introduction and Summary ............................................................................................................. 3 Background ....................................................................................................................................................... 8 The Tipi Model Approach ............................................................................................................. 11 Summary of the Tipi Model ..................................................................................................................... 12 Elements of the Tipi Model ..................................................................................................................... 14 Canadian Law, Policy and Standards ........................................................................................ 15 The Indian Act .............................................................................................................................................